| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Inis (2016) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.95] |

| BGG Rank | 100 [7.83] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Christian Martinez |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

I don’t really feel like I’ve given Inis the best possible crack of the whip. It’s been languishing on the ‘to review’ pile for a year and a half because I thought ‘I suspect this is a better game at higher player counts’, and I’d only managed to try it out with two. I don’t review games, as far as I can, unless I’ve actually done my level best to get the most out of them and play them on their own terms. So I resolved to wait until I’d given it a few tries at a higher count. Due to various things that never happened and I’ve given up on the hope it will. So that’s what you need to bear in mind here – this is a review of Inis as a game for ‘Couples and Bestest Buds’.

And the good news there is – it’s actually great at the two player count, but you obviously lose out on a lot of what likely makes Inis exceptional. That is to say, the politics baked into the table talk and the clever waltzing system of multi-aggressor combat. A read of the rules and a bit of theorycrafting means I can certainly be convinced there’s another half star in here if you’re playing with four people, but I can only review on the basis of my own experience. Still, there’s probably value to be had here in talking about what makes Inis work for people that may struggle to get a larger group together for the event.

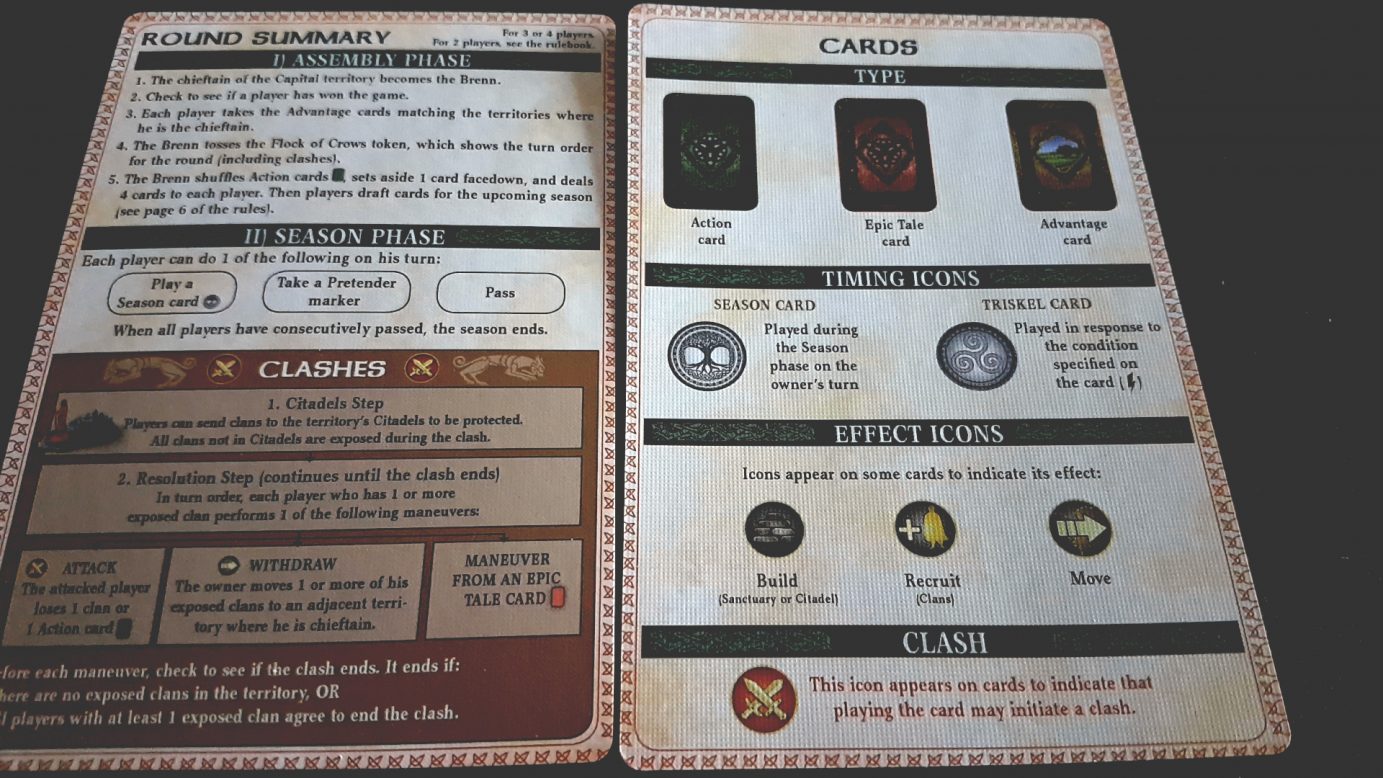

Here’s the thing about Inis – it’s not a game that opens itself easily to people. The rules are surprisingly svelte and elegant – you’re unlikely to frighten anyone away with the initial explanation. Each player takes control of a bag of clan markers and a hand of cards that is picked out through a draft. Cards are either ‘season’ cards, played sedately on your turn in the usual manner. Others are ‘triskel’ cards that are played in response to a specific thing happening on the board. One player is ‘the Brenn’, which is a temporary leadership role that has a kind of ceremonial facility – the Brenn is the one that deals out cards, chooses where explored territory will go and so on. Players will acquire new cards by virtue of owning parts of the map, or achieving things that generate ‘epic tales’. That’s about it, until it comes to the first skirmish. Nobody need feel intimidated when faced with a rules reference that is quite this compact:

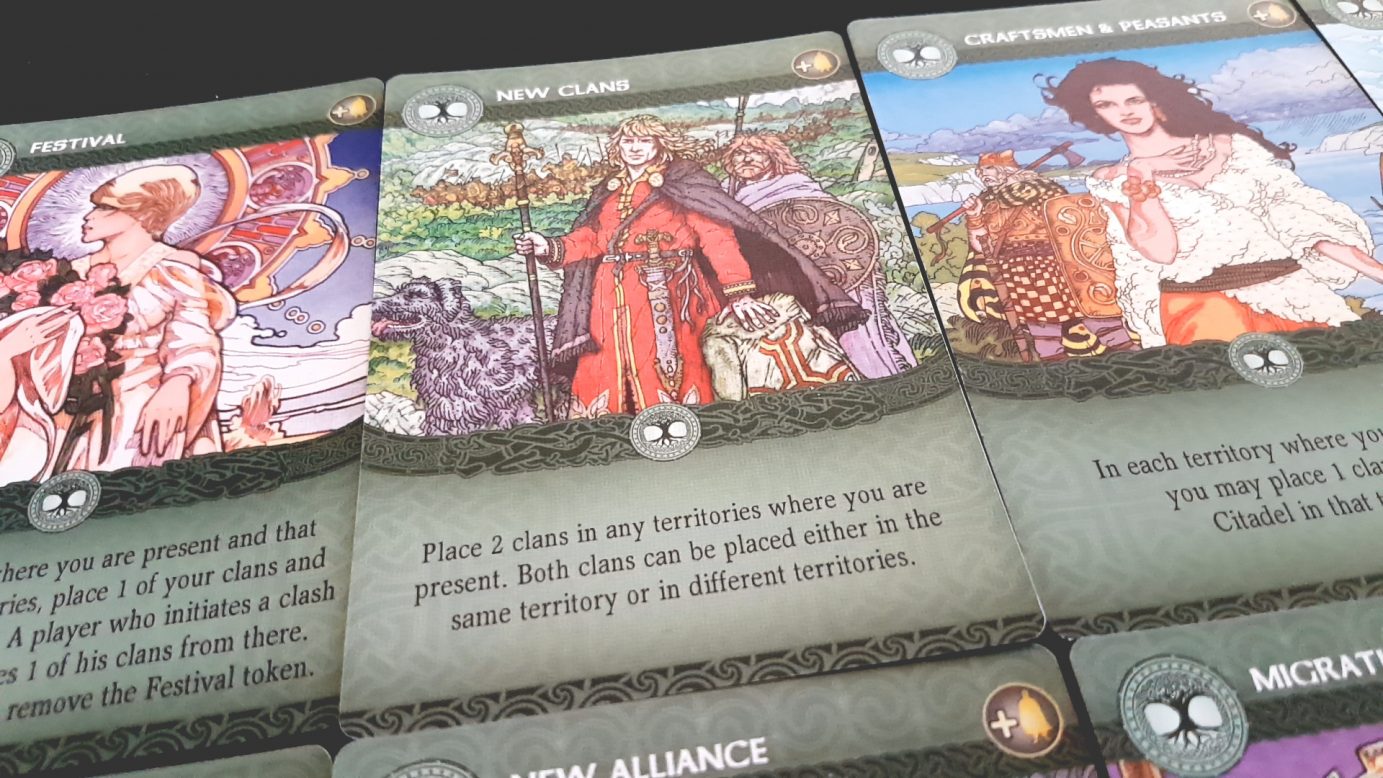

The cards you’ll play have all the effects you’re thinking of – they let you add new clans to the map, move them around, and initiate battles. Some also let you place citadels, where clans can be protected from a raging conflict, and the valuable sanctuaries that are the bedrock of one of the game’s three victory conditions. However, others have more subtle effects. They let you grab a card that someone else has played and discarded, or counteract the last action someone else took. It’s not a comprehensive toolkit – there are only sixteen of them in a four player game – but it’s enough to let some Celtic magic emerge from the table.

So yeah, nothing in here to scare people off – but understanding the rules of Inis is the easy part of playing it. To really get the most out of your time, you need to understand the dance. Inis presents itself as a standard ‘dudes on a map’ game, but that’s the wrong frame of reference. Inis, at its heart, is a ceilidh. It’s a series of wild, reeling jigs where you and your opponents will interlock arms and merrily spin each other around a wildly uncontrollable map as they each try to meet the victory conditions. It reminds me not so much of a game of area control as it does the formal Scottish country dance classes I was forced to attend as a child.

‘Walk four steps, turn, walk backwards four steps. Repeat, and then ladies dance under the man’s arm. Then polka!’

And yeah, that sounds easy – until you actually try to do it in sync with another person, in real time, while all your friends are giggling and your body refuses to actually behave because you’re holding a girl in your arms for the first time. That’s the experience of Inis. It’s the Gay Gordons played out in cardboard.

The three victory conditions of the game reflect this well – you can have clan members in six territories, or you can have command over six opponent clan members, or you can be present in territories that hold a total of six sanctuaries. It all sounds so easy until you realise that the rhythm of this is handled by an uncertain draft of cards where everyone is looking for the leverage needed to secure their own position while unseating yours. Thus the dance – someone marches soldiers into your lands so you turn-two-three-four and withdraw-two-three-four, allowing you and them to gain and recede influence at the same time. You’ll all be waltzing around the map in this manner, constantly driven forward and backwards by the relentless drum-beat of conflict. You lead, they follow. Then reverse, and repeat. Now everyone spin and swap partners, and polka!

You can see how this works in the battle system of the game. Citadels in an area permit the defenders in an area to move clan members out of the conflict. They’ll return safely to the region at the end of the clash. You send in your armies, and the clan members of your enemies turtle up and then the exposed members gently fade away into adjacent territories. Often war in Inis resembles not so much the battlefields of Bannockburn as it does an experiment in homeopathy – a constant dillution of force. But then your opponent plays down a card that permits them to reassemble all those dissipated troops in the territory that they just vacated, and suddenly the dance steps are reversed. Inis is a game of feints and endless guile. The way the cards work together can often achieve acts of performative treachery that are all but magical.

It doesn’t always work like this of course. Sometimes people don’t want to dance. They want to fight. And in that case combat is remarkably brutal. You take turns to knock lumps out of each other, choosing to attack, withdraw, or try to negotiate an end to the clash. If you attack, your opponent has two choices – remove one of their clan tokens from the territory, or abandon one of their action cards to the discard pile. The latter response is one of Inis’ more elegant balancing mechanisms. If you end up with a handful of dross after the draft, all it does is make you more belligerent when it comes to combat. Nobody wants to give up a card that has an important tactical benefit, but nobody cares about losing a card that is useless to them. In this, combat in Inis has an important psychological aspect. It’s not just about who has the largest number of troops or cards. It’s about who is most willing to sustain loss. Or rather, who seems most willing.

And loss in this respect is more than just about warriors and cards. It can also mean loss of territory and the advantages associated. The cards that you pick up for being in control of an area are occasionally of tremendous value. The iron mine card for example lets you dial up the threat of combat by forcing an opponent to lose a clan member and a card. Losing control over a territory like that can massively shift the balance of power and as such it distorts the risk topography of the entire map.

The citadels and sanctuaries you can build do much the same thing. Defensive structures let you create choke-points and beachheads because the difficulty of dislodging an enemy when they have multiple citadels is enough to ensure it’s rarely worth the stress. Sanctuaries, driving victory as they do, are the opposite – they shift the reward ratio so that even significant risks might be worth taking. Territories in Inis are three-dimensional entities, and everything you do during the game shapes and moulds their profiles like you’re going to town on a lump of well-worn plasticine.

Making this all more densely layered in the presence of epic deed tokens – you pick these up for some especially cunning activities conducted in the pursuit of victory. These are wild victory points, each adding one to any individual victory condition in the final reckoning. If you have control of only five territories, your epic deeds will round that up to an even win and then that’s it.

Except… it absolutely isn’t.

Here’s the next genius thing that Inis does to encourage a vibrant and exciting game experience. When you hit the threshold of a victory you don’t simply get to say ‘I win, go me’. Instead you visibly take a pretender token, and if you’re still winning at the end of the next round, that’s when you get to declare victory. There’s no slinking into first place here. You don’t even get to do it covertly when nobody is paying attention. It’s something you do on your turn when everyone is watching. It’s like a starter pistol firing – it converges attention onto the fact that the game is maybe about to end and if you’re not going to lose you’re going to have to unseat the claimant to the throne. Either by achieving a victory condition of your own, or depriving them of the one they have worked so hard to achieve. At the end of this dance, partners don’t elegantly bow to each other. They clamber over the chairs and push people out of the way to make sure they’re the first one out of the dance hall and into the cool night air beyond.

All of this is why I haven’t managed to get Inis played at more than the two player count. There is so much density to the experience that it bends inexpertise around it like a black hole. It would be like throwing a startled donkey into the middle of the school formal. Sure, you’ve added ‘another participant’ but you can’t expect that you’ll end up with anything close to what you were hoping. The process of building up skill with Inis is one that takes time. Leave that out and you’ll find everyone suddenly standing on everyone else’s foot.

But as a two-player game, it does have some obvious structural weaknesses. Diplomacy lacks bite when you are only focused on each other. It becomes too easy to calculate the relative strength of your negotiating positions. It’s better when you can add a veil of mystery to the cold-hearted calculus of conquest. ‘Look, if you concede this battle now we can live in peace and both gang up on Jasmine who is only one territory away from claiming the throne’. Or, ‘You know if you continue on this path you’ll find Roz slips in behind you and carves up the territory you just vacated. So let’s both agree to an orderly withdrawal of our troops’. The equivalent at two players is just standing with differently sized lump hammers until one player, usually the instigator of the clash, gets what they wanted in the first place. It’s hard to have nuance in discussion when there’s no matching nuance in the game state. I imagine, because I don’t have any direct experience to say anything stronger, that things get much more sophisticated when you can insinuate hidden motivations of nefarious others into the suspicious minds of your opponents.

At two players too the pacing feels… erratic. There’s a lot of nothing happening early on – there’s so much of the world to explore that expensive conflict seems unnecessary. There’s room enough for everyone. That extends to the card drafting too. In times of plenty, nobody need worry about contention over resources. That changes as both of you move towards the victory conditions and that pivot is quick enough to snap necks. And then, when you are actually wrestling with each other for the win it feels like a return to how the game plays at the start. It’s more drawn out that it should be and full of frustrating holds, counter-holds and counter-counter holds. The self-interest is too balanced and it puts a lot of emphasis on the game state. The better, more strategic player will almost certainly win but it’ll likely take a lot of very small, incremental steps to make it happen. It’s a tug-of-war where you can only win by gradually ensuring that you’re on better, more solid ground. Or, as is sometimes the case, that you get in hand a combination of cards so situationally powerful that it brings the entire game to a vaguely unfair conclusion. My belief would be at larger player counts that the imbalances of relative self-interest would ensure that the end-game is far more interesting than it is at two.

But still, it’s worth facing these problems just for the joyful middle, where every last action is part of a collaborative pattern of syncopated movement. It’s like synchronised swimming, but with little plastic soldiers on an elaborate, stylistic battleground. The ponderous beginning and drawn out end are relatively small tapers on an enjoyment curve that bulges generously towards ‘excellent’ in its most exciting moments. I hope one day to be given the opportunity to really try Inis out at its best.