Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Inis (2016) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.95] |

| BGG Rank | 100 [7.83] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Christian Martinez |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

While we can only review Inis as a two-player game, I have no doubt that when you try it out with a bigger group of people it’s going to shine like a damn diamond. Even at the (occasionally bumpy) two player mode it’s a gem of a game. Four stars of good. If Mario came along and jumped on the box with two of his friends, I bet another half star would come out. Inis is beautiful too, which some gorgeous art that I didn’t even mention in the review because people have disagreements on that score. Art is personal. Everything in life is subjective and I don’t know what on Earth any of us are doing here.

Anyway, I’ve given you only part of the Meeple Like Us package. Game reviews and occasional mild nervous breakdowns. The third spice in our secret sauce is accessibility, and that’s why I have gathered you all here today.

As Brenn of this particular topic, it’s time for us to make some hard decisions about Inis. Grab your axes, we leave at daybreak.

Colour Blindness

I always start a teardown with these sections because they’re usually the easiest to write. They get me warmed up for the more challenging analyses that happens in the later categories. Here we can normally say something like ‘Bad colours, no good’ or ‘Colours are fine’, or ‘Everything is double coded as it should be, come on, was that really so hard?’. It has been literally years I think since I said something new in this particular section. So imagine how simultaneously delighted and sad I am that Inis has managed a first for the blog!

That’s a little teaser. Let’s get the other stuff out of the way before we get to it.

The first colour-related thing that Inis will throw your way is that the epic tales and standard action cards are green and red, and this doesn’t work especially well for many players with colour blindness:

Epic cards are mostly ‘one off’ cards that represent specific, situational powers. However, they persist from round to round and you can see that Protanopes and Deuteranopes are going to have a trickier time than others when it comes to determining the composition of an opponent’s hand from card backs alone. It’s not impossible, but lighting is also going to play a big factor in this. There’s no equivalent issue with advantage cards (the ones of the far right) because they have a distinct, unique icon. Why not for the epic tales too? It’s not for the purposes of secrecy, because the different colours prevent that anyway. It’s odd.

The map, for a player with colour blindness, is going to be… difficult to parse. To be fair, it’s not easy for anyone because of the way the art blends together in a Picasso psychedelic freak-out, but other players will at least have distinctive colour palettes to ease that. Consider the image below for Protanopes and Deuteranopes.

And the ease of visual parsing becomes intensely problematic when you layer clan markers on top of it. There’s just so much going on and no easy way other than inquiring of the table to resolve colour misattributation.

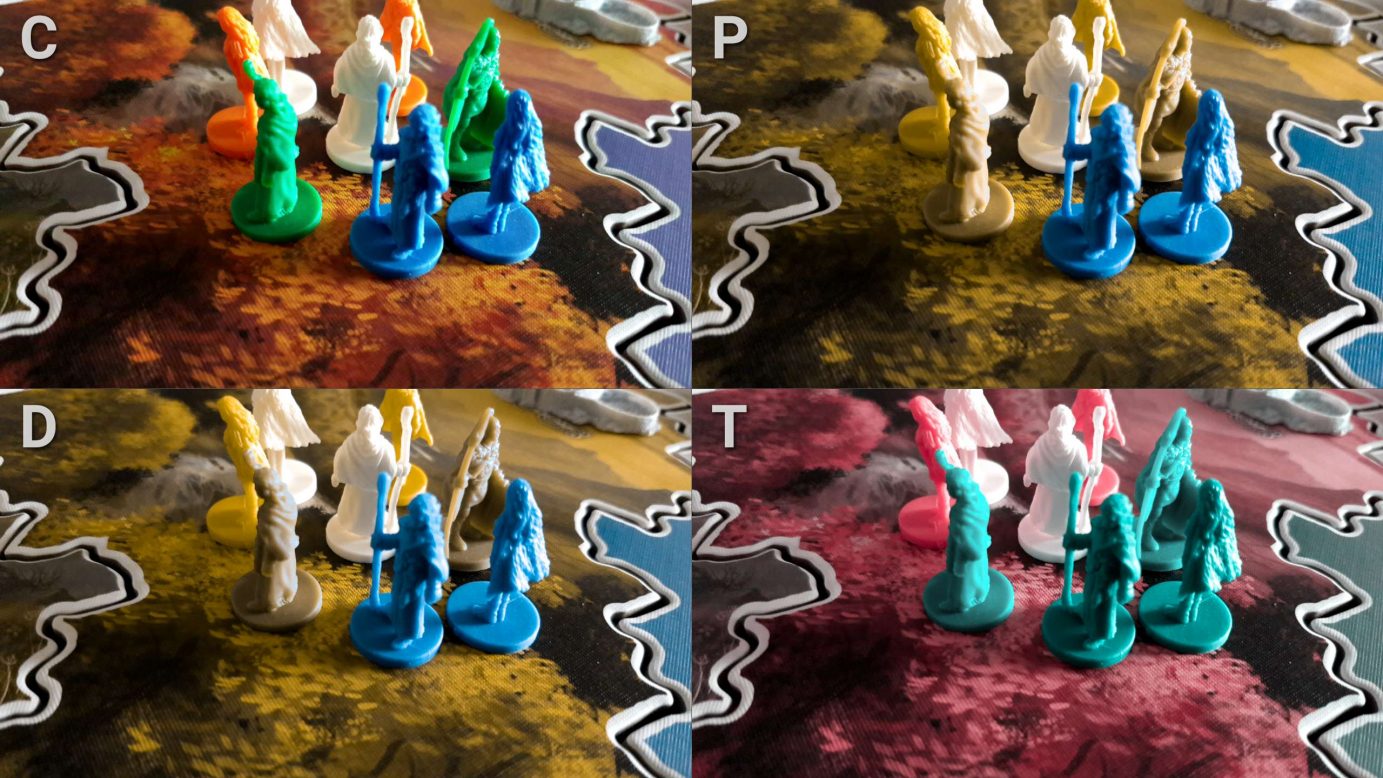

And now we’re into the new thing that Inis has done. I often talk about how double coding is the way to solve colour blindness issues in board games, and equally often bemoan games that have different colours for different players, but use the same mould for each of their pieces. As in, you end up with identical meeples in red, green, blue and black. Different form factors would instantly solve the colour blindness problem. It’s an extra expense though, and I appreciate for some game publishers it’s hard to justify. I don’t agree, of course, but I understand the argument.

Inis has a maximum player count of four, and it has four different molds of clan markers! So, you’d fairly assume that it was colour blind accessible, right?

But no!

Inis has instead taken the counter-intuitive move of sharing these four different figures between all four players, so everyone gets a mix of all. It’s such a massive missed opportunity that just goes to show why I do this kind of work. This is a perfect example of a game that could become meaningfully more accessible simply by slightly changing the way it presents itself. Just use one figure in a consistent colour instead – if Inis had done this it would have jumped several grades in several categories in this analysis.

This point is going to come up several times in the teardown. Be prepped for it. The clever thing Inis has done here is give me a brand new case study that I can constantly reference from now until the day I die.

We don’t recommend Inis for players with colour blindness.

Visual Accessibility

I’m going to say right from the start that I think Inis is meaningfully unplayable for someone with total blindness. There are massive problems from the card draft, to ascertaining game state, to making decisions about direction of movement, combat and withdrawal. Without having a dedicated support-player providing insight and clarification about what’s happening, I just don’t imagine it’s possible.

Consider the early game state above. It’s possible to verbally describe this but what’s missing is the vastly important payload of implication. The specific arrangement of clans in territories, where they are, and what that terrains do – that’s all vital information. For example, if the blue player attacks the plains then both of those other clans could withdraw to the nearby area with a sanctuary, and that has an impact on scoring. In late game scenarios, that might be all someone needs to actually win the game.

The cards players hold contain nuanced actions that can have sophisticated impact on the game, and they’re held secretly. You could play them open but it would be immensely detrimental to play. You’d break the veil of uncertainty that otherwise exists in a draft – knowing someone has the counter card is different from suspecting they do. Epic tales in particular have powerfully situational effects and you’ll want to hide the circumstances upon which you’ll be able to use them. Otherwise people will work to avoid putting themselves at risk.

A lot of information in the game is tactile, but I’ll bring up again this issue of everyone having several different figures rather than each player having one specific figure of their own. You can investigate, by touch, the presence of citadels, the capital and sanctuaries. That’s great. You can identify presence of pieces by touch. That’s also great. But you can’t determine ownership of pieces and you absolutely would be able to do that if you knew each player had a reliable figure to represent their clan.

Problematically too, some tiles have unique effects on them that apply, and this is written only on cards and/or the board. That’s less of an issue than managing the secret hand of cards, but it’s something that’s easy to overlook unless everyone is paying attention. You don’t want people to be in a position of having to announce when a negative effect should be applied to them.

Unfortunately we absolutely cannot recommend Inis in this category, and had the figures been more accessibility allocated we might have been able to make this a tentative grade instead.

Cognitive Accessibility

I’m not going to spend a lot of time in this section because you’ll have already gotten the gist of it from the review.

The rules are not necessarily the biggest barrier here – rather, the issue is one of interpreting and acting upon the synergy of card opportunities and game state. That requires a lot of sophisticated tactical and strategic planning combined with relatively sophisticated literacy and careful consideration of impact. For example, a player might lure you into a combat so they can have you remove one of their troops. They then play the bard card as a triskel to gain a deed token (one of the game’s wild points), and then withdraw to an adjacent territory to claim a sanctuary which, with the deed, allows them to claim a pretender token. If there is also a citadel there, all you’ve really done with the attack is put them in a position to win the game. Alternatively, someone might move their troops into your territory, then play Ogma’s Eloquence to instantly end the battle. That allows dominance in a way that less intricate mechanisms would not permit. This kind of thing is the heart and soul of Inis.

It’s relatively easy to say ‘More troops means more chance of winning a battle’ but the negotiation aspect of a clash means that it’s never quite that simple. Similarly the presence of citadels and the ability of enemies to withdraw troops (or play triskels that work in their favour) makes the actual outcome of a battle difficult to predict. Game flow is consistent in terms of how it works its way around the table, but game flow in terms of how state is manipulated on a turn by turn basis is very complex.

For those with memory considerations, the largest issue is going to be in the draft because it really helps if you know you sent a particular card on to an opponent. It’s also very valuable to know which cards are in the deck as a whole. Your awareness of the full game state will never be complete, but being aware of the possibilities is an important part of playing well. Similarly, knowing the broad sweep of the epic tales deck and under what circumstances it might contain problems is valuable.

This is not a game we can remotely recommend in either of our categories of cognitive accessibility.

Emotional Accessibility

Inis struggles here too because it is pointedly PvP but in a way that emphasises players being cunning and tricky. It’s not a game of simple combat where you move troops and throw dice. The combat is deterministic in terms of its outcome – there’s no randomness other than what cards are in your hand at the start of it – but still intensely unpredictable. Add in the various cards that countermand your cards and simply getting anything you want out of an encounter can be fraught. Numerical superiority does not translate into advantage in the way you might intuitively think. That creates recurring game loops where there is a sense of elation followed by a sense of frustration. Much of the way the epic tales in particular work is as a series of ‘take that’ powers, as is the case with some of the land based advantage cards.

Players can absolutely undo all your hard work turn to turn, and can work together to block your progress. Indeed, the negotiation elements in the game mean this is almost certainly going to happen and it’ll occur more intensely the closer you are to winning. When you meet a victory condition you can claim a pretender token during your turn, and you can’t win unless you do. The result is that you spend a turn taking an action that is the equivalent of yelling ‘Come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough’, and that will almost certainly galvanise the table against you.

Victory is hard to achieve at the best of times, because it’s constantly a game of shuffling around and being tugged back when you get too far out of line. Citadels and festivals in particular can make it difficult to enforce your will and bring things to a meaningful conclusion. The result of this is that it’s, apparently, often the case that players will form unofficial alliances where the job of a player in the rear of the line of succession is to essentially grant the win to another player. It’s not formally stated in the rules, but I’ve seen this comment made often enough in discussions of Inis to take it seriously.

Players can’t ever truly be eliminated in Inis, but they can come so close that it barely matters. The rules have a specific clause for handling when someone is completely wiped from the board, and while it keeps people playing it doesn’t at all put them back in a position where they’re likely to win. Mistakes in Inis linger for a long time, because every time you play a card you lose it from your hand and may not see it for a number of future rounds. If you really need the ‘new clans’ card you might see it once, use it, and then never see it again. The druid card permits you to steal a card from the discard pile, which helps with this, but that assumes that someone plays it and also that you have the druid card to play.

We don’t recommend Inis in this category.

Physical Accessibility

The board of Inis is modular but it fits together like a jigsaw. It’s not a snug fit so it can absolutely still be knocked apart, but it’s more robust than you’ll see in many games. The tiles are thick and heavy and give plenty of room for all the many tokens that will sprawl atop them. On the downside, this is a board that spreads out like melting butter. The far end of the board might be very far away.

Players will be expected to be able to move and collect their clan markers from territories, place clan members in citadels when appropriate, and handle the card draft that occurs at the start of every round of play. The good news is that none of this need to be done entirely by a physically impaired player. Card drafting can be as simple as holding up the choice for someone to see and then letting them verbally indicate which to keep. Shuffling of the deck and dealing of the deck is something that is traditionally handled by the Brenn, but it’s important for a good leader to delegate in any case. It might even add a bit of ambiance for a physically impaired Brenn to demand another player shuffle and deal in respect for their chief.

Most players will be working with four cards at a time, with perhaps a few epic tales throw in. As a result, a pair of card holders will be appropriate but the cards will need to be fully uncovered to reveal all their special effects and possibilities. The card holders would need to be generously proportioned though because these are oversized cards, much in the form of Dixit cards. Playing cards can then be differentiated by verbal or other indication.

Inis also benefits from its map by making verbalisation very straightforward. Every tile has profoundly distinct artwork, and a unique name. You can explain actions easily with things like ‘Play my third card, new clans, and place one clan in Stonehenge and the other one in the Iron Mine’. ‘Move my clans adjacent to the plains into the capital’. ‘I play my geas triskel to countermand your action’, and so on.

We’ll recommend Inis in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

My version of Inis comes with some stunningly striking box art showing a prominent (although almost certainly very chilly) woman warrior seemingly leading a unit of grizzled bearded men. This is matched by the figures in the game, around a quarter of which are women and the rest are stereotypical Burly Men Warriors. The manual, unfortunately, defaults to masculinity in its descriptions. There’s a lot of ‘he takes this’ and ‘when he wants to do that’. It’s far from the worst game we’ve seen from an inclusion perspective, but it could be a lot better.

Unfortunately, the newer edition of the game (which I’m told has only an art change) gets rid of the woman on the cover in favour of a male druid pointing at the moon. It’s still gorgeous art, but I can’t help but feel like it’s a step in the wrong direction.

/pic4739757.jpg)

Cards in the game similarly skew towards men, although not exclusively. The New Alliance card for example shows a man and a woman, and the exploration card shows our cover model stepping onto a new land. The Craftsmen and Peasants card shows a wool-draped woman and a Stern Man. It’s better in this respect here, although again it’s not as good as one might hope.

You can pick up Inis for about £50, which is pricey but not excessively so for what you get. It’s a game that I suspect thrives especially at higher player counts than what we tried, which is two, but even at that count it’s a great game that I enjoy a lot. It is though a game where you will need everyone involved to be versed in it’s the ways in which its game state mutates. That can make it a tough sell for someone playing outside the confines of a dedicated gaming group.

We can tentatively recommend Inis in this category.

Communication

Inis requires a good deal of literacy because its cards are all text based and have few iconographic elements to assist. Some symbols are used, but they give only a fractional understanding of the specifics. For the standard cards dealt out as part of a draft there are sufficiently few of these that they could likely be committed to memory. The epic tales cards are more problematic, as are the terrain advantage cards.

Negotiation is an important part of resolving clashes, and in some circumstances you’re almost certainly going to see the Resistance issue appear – this isn’t a forum where everyone is supposed to get a chance to calmly discuss things, and you may find yourself making proposals and counter proposals in response to someone that is actively trying to make you seem like a distrustworthy agent. There isn’t so much scope here that the discussions will be very wide ranging, but they could be a barrier to play for some people in groups with highly combatative personalities and large scale engagements.

We can only very tentatively recommend Inis in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

Inis has had something of a rough ride in the teardown and it doesn’t really get better here. We recommend the game in only three categories, and two of those are tentative. There’s only one real intersection here that matters – physical impairment is going to make communicating parts of the game more difficult if verbalisation is a problem. Everything else is already invalidated by one of the component grades, or is unlikely to be a substantive intersectional issues (socioeconomic factors, for example).

Inis can be a reasonably long game, getting longer in line with with player count. Games of 90 minutes are reasonably common. If playing with equally skilled people all equally keen on winning, well. The nature of the win conditions mean there’s a lot of time in the end-game spent on ponderously cycling through almost wins until someone finally nails it. It’s not a game that survives well if someone drops out, although you can treat it Small World style and just have their clan slowly disappear from the map. The problem with that is that some players will be in a better position to take advantage of that circumstance than others, so it’s going to be unfair on everyone else left.

Conclusion

Inis is a great game, but not so great an accessible product. And yet, there’s a more accessible game in here if individual figure molds were assigned to players rather than mixed through everyone’s different clans/ It’s a great example of how easy accessibility improvements can be, and a terrible example of how impactful it can be to ignore the topic.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | D |

| Visual Accessibility | E |

| Fluid Intelligence | E |

| Memory | E |

| Physical Accessibility | B |

| Emotional Accessibility | D |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | C |

| Communication | C- |

My guess is that had Inis done this we’d see a recommendation (perhaps tentative) for colour blindness, and we’d see the visual accessibility grades improving from E to perhaps C-. I might even be inclined to improve the E for fluid intelligence to a D+ or perhaps even a C-. Just because parsing the map would be easier if there was a consistency of visual language. None of these would be such large changes that our teardown would be gushingly positive, but the difference is perhaps between nobody being able to play the game easily, and thousands of people being able. That’s a big potential market increase.

Alas though it is our lot in life to see accessibility own-goals and misses everywhere we look. I’ll remind you all, as I so rarely do, that we are available for consultancy if you want to make sure someone has spent a bit of time thinking about these issues in your game before you end up on the business end of one of our kickings. We gave Inis four stars in our review, but as you can see from the teardown that didn’t save it in the least from the boot.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.