This review is a little bit of an experiment in branching out from the site’s core remit. Thousand Year Old Vampire bills itself as a ‘solo roleplaying game of memory, loss and vampires’ and I discovered it largely by accident. One of the things I’m doing this coming academic year is a course that involves roleplaying games (my job is great, if I haven’t made that clear before) and I wanted to broaden my experience beyond the confines of Dungeons and Dragons. It’s led to a borderline obsession with Blades in the Dark, and a small but growing collection of ‘weird’ RPGs – boxed, book, and PDF – being added to my physical and digital shelves. Thousand Year Old Vampire was mentioned in passing in a forum post and yeah – it was a strong enough pitch that I felt the need to check it out.

Since this is an experiment though, I need to make a few things clear. I don’t really have a deep mental bench when it comes to RPGs. My real experience is limited to a few forum RPG experiments and one live session at a convention. For unrelated reasons though I do have a very broad experience with the creation of characters in a lot of systems. I’ve owned a lot of systems. I’ve read a lot of sourcebooks. I just haven’t played much because they require one important and valuable resource – friends with the time, and desire, to play these games. And, you guessed it – I don’t have any friends.

That puts me in a weird position in that I can, for example, outline the rules of THAC0 and how the DC of later D&D editions refined and simplified the often archaic arithmetic that AD&D inherited from Chainmail. I can go on at length about the troupe based conventions of Ars Magica, and how the sheer specificity of the Warhammer 40K universe is a detriment to novice roleplaying. And yet I can’t really drill down into what it feels like to level up a character that’s part of an ongoing, vibrant campaign. I’m like an old-timey pirate you’d meet in a bar only to find out they’d never been on a ship more exciting than a local ferry.

The second thing that’s important here is that RPGs don’t lend themselves well to the MLU formula. How do you do an accessibility teardown on a game system that is found more in its players than in its sourcebook? How do you talk about – say – the emotional accessibility of D&D? The experience of players with a DM that wants to make them act in an overtly sexualised campaign is very different to those that make use of the various safety toolkits that have become fashionable over the years. The DM relays the world, interprets its rules, and makes up systems on the fly to accommodate human ingenuity. I’m not sure you can realistically pin any of that into an academic analysis of accessibility and – first and foremost – that’s what this site is about. But Thousand Year Old Vampire is a game that I think permits it more than most. It’s a good system for sticking a toe in the water.

Raise your hand if you’ve got an issue with any of that. No, put your hand down you fool. I can’t see you. We’re going ahead with this regardless. Just keep all those caveats in mind. They are the first of the memories you’ll record through the course of the review.

Thousand Year Old Vampire works on the basis of a series of numbered narrative prompts that you progress through – forwards and backwards – as a result of dice rolls. You roll a ten sided dice, subtract the value of a six sided dice, and add the result to the prompt where you currently located. The trend of the game is ‘upwards’, and as you won’t be surprised to know the last few passages in the book are all about endings. Your vampire might be a brief, unhappy thing overtaken by time and destroyed before it has a chance to unlive. It might buck the trend and revisit earlier passages again and again, where they encounter the prompts that trigger on a seond and third visit. You don’t know – your vampire merely has the potential for a lifespan of millennia.

Before you plunge into this process though, you create your character. There are few rules or restrictions here – the game itself is so loose in its prompting that really it’s an exercise in enforcing consistency with your own creativity. You’ll decide on a a few mortals that you know and an immortal that sired you. You’ll define a background, and some skills and resources with which that background furnished you. They might be grand things like ‘A massive army that can defeat all foes’, or small mementos such as ‘the bible I was given by my abbot’. Your skills can be anything from ‘I can work magic’ to ‘I am passingly literate in Latin’. It doesn’t matter – these things have no mechanical weight.

Most important are your memory slots, and it’s here where Thousand Year Old Vampire becomes a genuinely poignant experience.

I’m a big fan of Peter Capaldi’s Doctor, and especially of the character Ashildr who he inadvertently cursed in a relatively early expedition in the TARDIS. She’s a Norse puppet maker who the Doctor makes functionally immortal. We only find out the consequence of this when we encounter her in a later episode and it’s always struck me as an almost unimaginable nightmare of existence. The Timelords can cope with their long lifespans, they’ve evolved for it. Not so with the rest of us in the franchise. The human mind has a fixed capacity, and new memories inevitably overwrite old memories. Everyone she meets is a brief flickering shadow with only transient existence. Her lovers, her children, her friends, her family – they will light up and then extinguish, leaving her once again alone without even the memory of their times together to warm her. She turns to extensive journaling to record some flavour of her history – 800 years of temporary names, forgotten jobs, lost adventures, wounds and glories – as unreal to her as the adventures of the Fellowship of the Ring are to us. She’s cold, and arrogant, and vengeful. Wouldn’t you be also, if someone had inflicted such an vicious unkindness upon you?

It chills me.

People sometimes say things like ‘I wouldn’t want to be immortal, I’d get bored eventually’. Imagine being a centuries old monster where the worst thing to happen was that there was nothing left worth watching on Netflix. What a luxury, compared to the alternative which is to become literally unmoored from your own life and the things that once gave it meaning. To see yourself as distant and remote from humanity not because of the fact of your immortality but rather the eventual inevitable consequence of it.

Thousand Year Old Vampire is – well, that. A profoundly sad experience in exploring the loneliness of immortality as the centuries grind on. That’s why it doesn’t matter whether you command great legions or simply have a treasured childhood book. As you make your way through the years you’ll lose them, or simply forget you have them. It doesn’t matter the enemies you create or the allegiances you form. They’ll fade into wispy memories before they eventually float away along the river of time.

It’s strangely affecting.

The system enforces a hard limit on your memory. You can have five ‘slots’ for memories, and each of these contain a maximum of four thematically linked ‘experiences’. Every time you encounter a prompt, you write an entry that outlines one of these experiences, and it has to go somewhere. If you have no place it can go, an existing memory must be sacrificed. It’s scored out, and no longer available to you as a story path through the game.

Your job here is to document this experience on your sheet, in a way that makes sense given the memories you have left streaming out behind you in your conscious memory. It might seem like little more than the creativity exercises that you see in any writers group, but it’s a bit more than that because you have a relationship to the world expressed through the lens of your vampire. You know where they are, what they have done, and as a result what kind of mortals are likely to come to mind as new enemies, allies and victims.

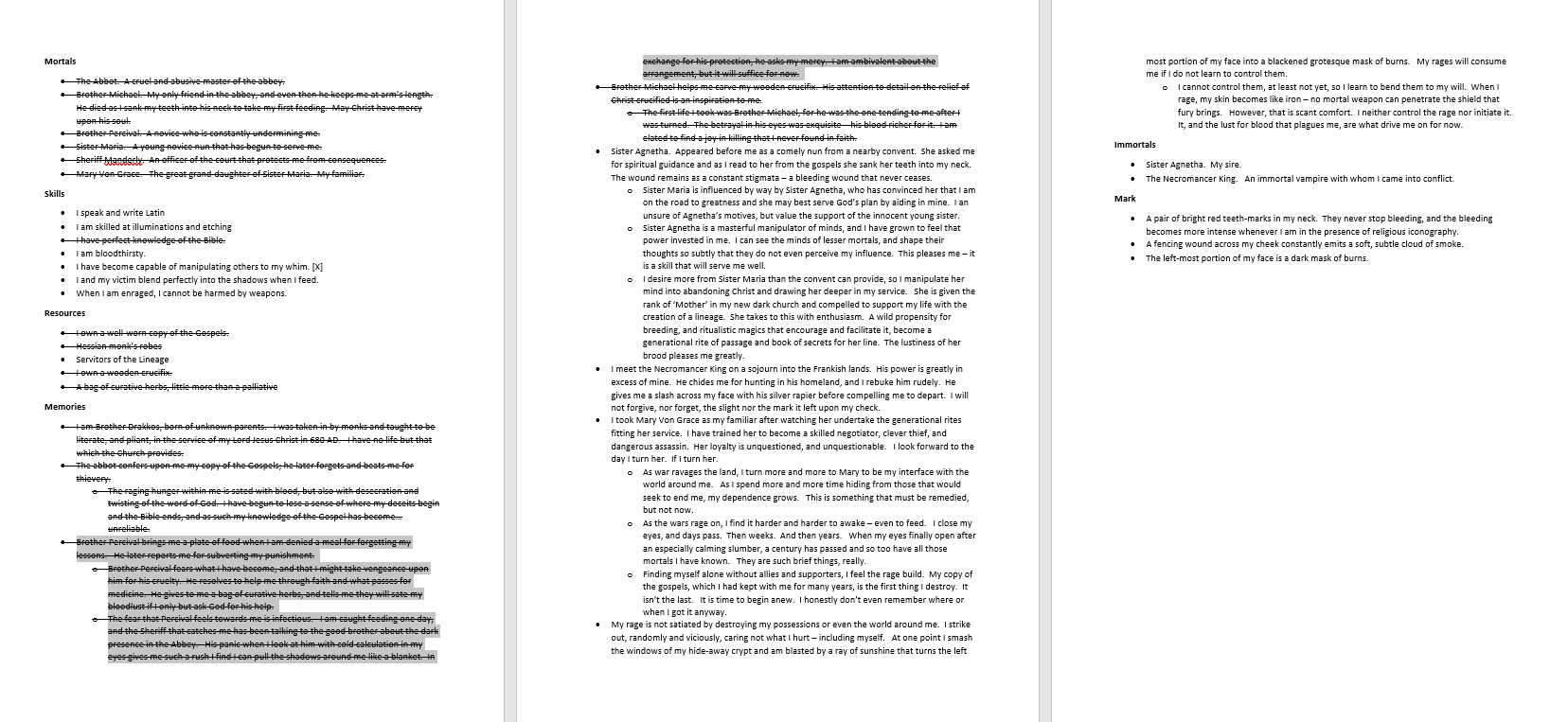

My first prompt was to ‘destroy someone close to you’, which is the prompt you see in the image above. My Vampire was ‘Brother Drakkos’, a young monk unhappy in his life. He was the servant of a tyrannical and abusive abbot, disliked by the other novices, and had only a close friendship with one other. So, who is the mortal character that is close to me? Well, it’s Brother Michael – my only friend. Why did I kill him? I killed him because he was the one left tending me after I was turned. His mercy put him in proximity with a monster, and he was fed upon as his reward. Here’s the experience as I recorded it at the time:

- Brother Michael helps me carve my wooden crucifix. His attention to detail on the relief of Christ crucified is an inspiration to me.

- The first life I took was Brother Michael, for he was the one tending to me after I was turned. The betrayal in his eyes was exquisite – his blood richer for it. I am elated to find a joy in killing that I never found in faith.

Notice how it’s struck out? That’s because as the game went on my vampire simply forgot it. He forgot it all – the friend, the crucifix, and even the brutal joy in the kill. Those formative moments of his life broke apart and floated away, like much of his experience. He forgot his sire, the sinister sex-cult that served his lineage, and the circumstances of his own existence. Mechanically this only has a minor effect. Occasionally you are instructed that the context of an experience must link to existing memories or suffer increased losses. Thematically though it is astonishingly effective when it comes time to reflect upon your life, and death. This is where the sadness in the game comes from – the inexorable knowledge that even the greatest triumphs will eventually be for naught.

As to experiences themselves, they come in two ‘flavours’ depending on how long you want to spend within a single life. You can write a single sentence: ‘This happened, and it made me feel this way’. Or you can take a much longer, detailed route through a story and write full diary entries for each incident. Given my propensity to bloviation, I obviously went for the wordier approach. Really though you can have as intimate a relationship with your character as you like. You can record their experiences with perfunctory bureaucracy or you can delve more into how things feel, and the depths of outcome that will inform future experience writing.

But here’s the thing…

I found myself gently absorbed by Thousand Year Old Vampire, but ultimately unconvinced by what it promised me. I remind you: ‘a solo roleplaying game of memory, loss and vampires’

Bits of this are unquestionable. It’s definitely about memory, loss and vampires. And it’s certainly a solo experience. It’s the other parts that I think promise more than the system can deliver. ‘roleplaying game’.

Remember the caveats from the start of this review? Keep them in mind here.

Firstly, I just don’t think this is a game at all. Its not rules-lite, it’s basically rules-negligible. What stops me resolving every prompt with ‘Rocks fall, everything dies?’. Nothing, really. The prompts are narrative beats, explored and resolved with creative writing and reference to what is recalled about the past. This might seem like a picky, semantic point and in large part that’s correct. But the undervalued thing that rules let players do is confound their own expectations. When I roll a critical hit in a combat round, it has the effect of creating unpredictable textures in the game. When an opponent player seizes a resource upon which I had counted, it forces me into working through a backup plan or alternate strategy. None of that happens when I can critically hit at will, or simply say ‘And I get to use that resource too’. The extent to which the prompts in Thousand Year Old Vampire create moments of poignancy depends on the creative skill of the player. It’s only as good as the fuel that goes into it – badly conceptualized experiences lead to boring, unsatisfying prompt resolution. That’s not bad, but I don’t think it’s a game. As a consequence, its players aren’t actually playing anything.

What Thousand Year Old Vampire strikes me is as something different to what it claims to be. It’s not a roleplaying game, it’s a roleplaying story. Except… it’s not really that either. I don’t think Thousand Year Old Vampire outputs anything that can fairly be described as a story as opposed to a series of often causally disconnected narrative vignettes. That’s clearly an intentional (and clever) part of the design. The grouping of experiences into thematic memories which are then discarded in chunks creates a thoroughly disjointed series of observations. When you ‘forget’ a memory, it gouges massive chunks out of the web of associations you have been building because experiences will thread through multiple different and connected arcs.

Even the recording of the experiences defies easy reconstruction – a wonderful way to cut the lines of mooring that keep your character situated in reality, but a bad system if you want to be able to coherently retell to another person the events that occur. That’s even true if that person is yourself some time later. It’s marvellous the way the game creates a character that often acts in ways you didn’t expect because of the alien fragility of memory. Stories though need to make sense in order to be convincing, and it’s a notably unconvincing framing to say ‘Oh yeah, he forgot that happened’ in order to explain the weird jarring inconsistencies in the retelling.

So what are we left with? It’s not play, it’s not a game, but it’s certainly a Role. And really that’s what I think you get with Thousand Year Old Vampire. I think you get a system for generating compelling, interesting and unexpected roles. It’s a character generator. You can take the output of your session and seed it almost perfectly into the framework of another campaign, or novel. You can write aspects of personal history into a world history, and seed that setting with clues that even your vampire wouldn’t recognise. If you took your creature and put him into your RPG you’d end up with more than an NPC your players could fight. You’d give them an abomination that your players could hunt. You’d provide an antagonist so viciously inhuman that it would be possible to hate.

What comes out of your time with this game is a complex, well-motivated monster that did things even you found surprising and occasionally horrifying. My second vampire became intimately involved with the slave trade in Colonial Africa. Not because I wanted that, but because it was a natural direction for his story to go given what had happened to him and the prompts he encountered. Yes, I wrote that into his story. But I didn’t want to write it. Don’t blame me, I just work here guv.

Thousand Year Old Vampire is more of a creative writing exercise than a game in any meaningful sense, and as such my end conclusion of the review is ‘I probably shouldn’t have reviewed it at all, it’s way out of scope for the site’. I found myself intrigued and drawn into the design of the system though. It’s unusual. It’s profound. It’s occasionally disquieting. It produces outputs that are contextually appropriate from the inputs and yet sometimes bizarre and unexpected. I can’t recommend it to you as a roleplaying game, but I would certainly urge you to check it out as a tool for exploring the subtle horrors of alien motivations.

if you’re interested, you can check out a couple of my vampires on Google Docs. This is Brother Drakkos, my first. The Young Lord MacDonald was my second.