| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | XCOM: The Board Game (2015) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.91] |

| BGG Rank | 913 [7.00] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 1-4 (2-4) |

| Designer(s) | Eric M. Lang |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

There are obviously a lot of differences between board games and video games. Board games tend to come in bigger boxes. Board games have an elasticity of availability that rapidly snaps between feast and famine. One day they’re a hard-to-find grail game, the next they’re two for one in a discount warehouse sale. Board games have an expectation of face to face social interaction, at least in theory, built into their very bones. Really, we could do this all day and never scratch the surface of the difference between the two different forms of gaming. What you might not have considered though is that board games, by their very nature, have to be transparent.

There’s no fudging in a board game – there are no hidden mechanics because at some point an actual person is going to have to do the work of handling the progression of game state. That means nothing is truly secret, even if parts of the game state may be obscured on a temporary basis. There are no mysteries in how the game works, because there can’t be. You can look through all the cards, read all the manuals, pore over all the documents. You might be asked not to, such as in a legacy game, but you can if you like. The game has nothing that it can keep from you.

Video games on the other hand are full of secrets because something else is handling the mechanisms that drive the experience. They can be absolutely stuffed with hidden systems of mind-boggling complexity and you might never even know they’re there. They might be learnable through deduction, or they might forever be opaque and mysterious. They might only come into effect under certain rare circumstances, or in reaction to emergent game states. They might never trigger. Ancient temples may go forever undiscovered. Complex weather-based combat systems might never be noticed. Deep and realistic ecological modelling may be rendered invisible through sheer ubiquity. A video game can be full of mechanics with which you never need to engage because some other agent is turning the wheel and grinding the gears.

Many in the board game community are dubious about, or even hostile towards, the idea of app driven games. However, it’s hard to deny that apps permit analogue games to explore design space that is otherwise fundamentally locked away. So it is with XCOM – this is a game that could not exist, in its current incarnation, without the incorporation of the app that acts as its beating heart. Bear that in mind as you read the rest of the review – this is a game that is only possible with the support of a digital tool.

The chances of anything coming from Mars…

However, that’s not to entirely dismiss the suspicions of those that would prefer apps remain out of their games. While XCOM as it is delivered couldn’t be replicated purely in cardboard and plastic, that doesn’t mean it would be an inferior game for the attempt. The app that is threaded through the game experience does a lot of work of conducting electricity through play, but in the process it handily obscures some fundamental design problems. The app is important – it makes XCOM a rich and exciting and vibrant game. It’s also a magic trick that focuses your attention with artificial urgency so as to hide the somewhat lacklustre gameplay mechanics that are to be found elsewhere in play.

Let’s not get too deep into the weeds just now – XCOM is a good game. It’s a game where you’ll spend a lot of time urgently dealing with an escalating litany of critical problems. You’ll decide before you’re ready, and commit before you’re sure. And then you’ll spend time slowly unspooling to find just how bad you’ve made the situation as a result of your own time-constrained choices. XCOM pretends that it’s about humanity versus the oppressive troops of a hostile alien force. The aliens though are just props – the antagonist of XCOM is the version of you that was playing the game during the app’s brutally stressful ‘timed’ phase. You’re not fighting off aliens – you’re cleaning up after the chump that panicked as the timer ran. Your opponent is the idiot that threw all of their most elite forces into a suicide mission they mathematically could not complete. That’s why XCOM absolutely could not work if implemented, as it stands, into an analogue form. All of the fun comes in the bell curve of tension that exists through the pacing delivered by the app. You could have a human referee and a pile of state randomisers – that could get you close. You’d still never meaningfully mirror the sheer algorithmic dispassion of an app throwing unending logistical horrors at you with the ceaseless, tireless precision of a Terminator.

This is pre-apocalypse

Put your objections aside then – the XCOM game needs the app because XCOM needs the tension. It needs the tension because the game itself is – well, it’s a little bit ropey. Certainly exciting, often funny, but effectively only because of how much it forces you to dwell on your own mistakes and deal with their consequences.

We’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves here, so let’s wind it back a little. You and as many as three of your friends are going to be taking on the role of the officers of the elite XCOM organisation. XCOM is a transnational military force tasked with keeping the Earth safe from relentlessly hostile and excitingly varied aliens. If you’ve ever played the video game you might be expecting a game of tactics based miniatures warfare in which you are selecting optimal cover and carefully triangulating firing positions. What you get is a gamified version of the world map that serves as a backdrop for the exciting alien combat that’s the focus of the digital versions. Here, you’re not commanding squads of soldiers on a turn by turn basis – you’re the officer dispatching them to their almost certain death. You’re not the interceptor pilot attempting to shoot down alien crafts – you’re the hanger manager checking your clipboard to see how many planes you can afford to dispatch. You’re the line manager of the scientists. You’re the mid-grade administrative aide controlling the budget. You’re not the hero – you’re the hero’s bureaucratic infrastructure. If anyone in XCOM had a badge and gun to slam down on the desk of some tightly-buttoned middle manager, you’d be the one sitting behind that desk.

War. War never changes.

It doesn’t sound like much fun I’m sure but it turns out that keeping an entire planet safe from rampaging extra-terrestrials needs more than the ability to aim a gun and shoot the bullets. I’ve referred previously on this blog to the design philosophy of ‘five fires and four buckets’. XCOM takes this to its logical extreme by giving you whole burning continents and neglecting to provide you with any buckets at all. Everything is burning and all you’ve got is a half-consumed bottle of Evian with which to fight the blaze. The real heroes here aren’t crying about their abducted sister or arguing with a skeptical partner – they’re desperately balancing a dozen spreadsheets where every single column is in the red and getting redder by the minute.

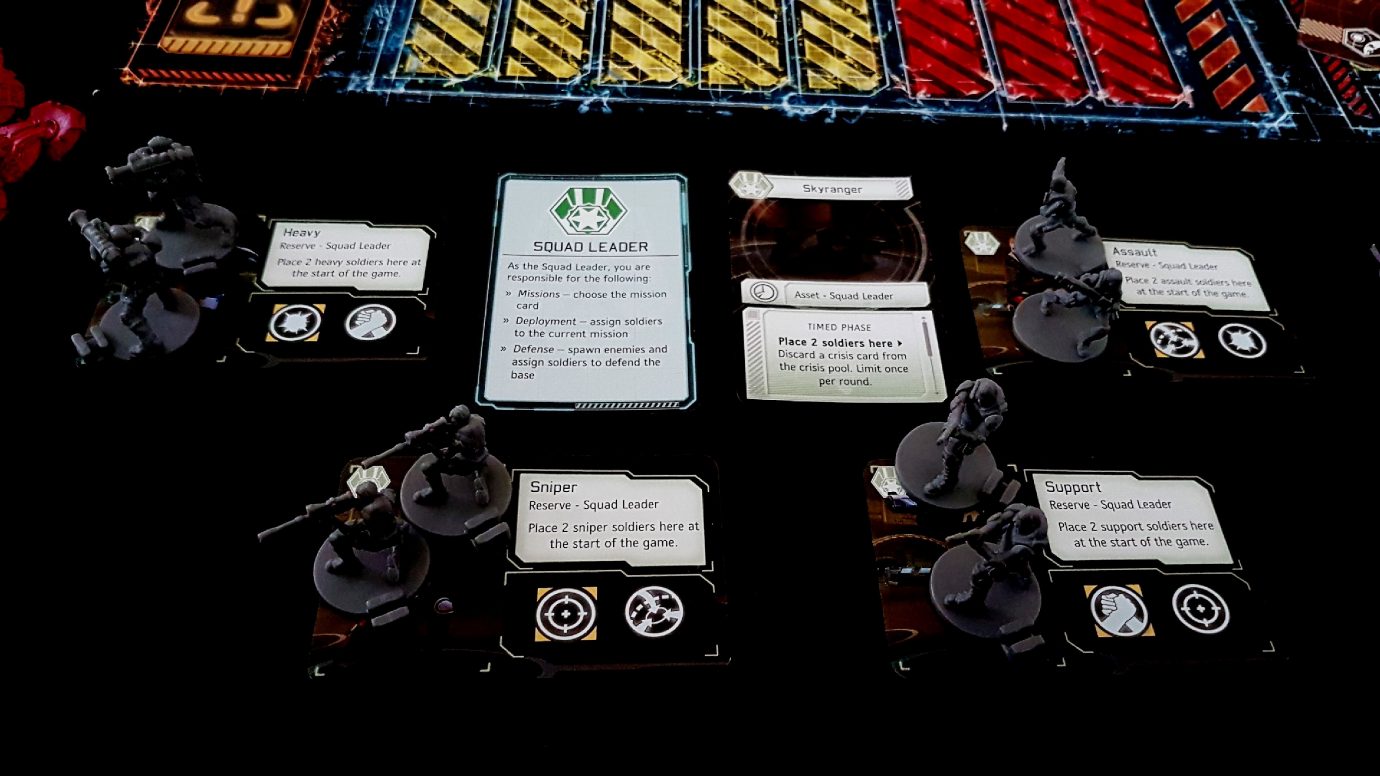

Take the Squad Leader for example – they have eight units of soldiers they can deploy between missions and base defence, and every single one of them needs to be paid for if they’re deployed. Apparently XCOM works on an ‘on call’ basis because it seems like salaries aren’t otherwise factored into the budget. What’s absolutely vital is that the squad leader applies the right soldiers, of the right skillsets, to the right tasks, in the right quantity. The million dollars you spend on a sniper you didn’t need is a million dollars that can’t be used to fund research. That’s a problem.

The view from my desk at work

Research you see is where you actually manage to build up the tools you’ll need to survive in the coming wars. Technology is key to mitigating the often psychopathic cruelty of the dice system around which XCOM is built. In order to research technology you’ll need scientists assigned to the three different research tracks. Each scientist costs, you guessed it, a million dollars to deploy because research isn’t cheap. Seriously, it’s not – every time I put together a grant proposal at work it’s like trying to salvage a workable meal from the leftovers in a corporate fridge. It might seem like the scientists have the easiest job here. You try putting together a meaningful research agenda on a budget that wasn’t so much garnished as it was eviscerated by ‘organisational overheads’. While you should have sympathy for the scientists though bear in mind that the million you spend on each of those also means you’ve got less to spend on air support for the planet.

We’ve got Top Guns working on it. Top. Guns.

Every turn aliens are going to be pouring in from the cosmos, parking their fire-engine red UFOs in continental airspace. As you might imagine, this has a less than calming effect on the population – nothing harshes the buzz of a Friday barbeque than seeing the imminent approach of an alien space-ship loaded up with fresh anal probes for assembly line insertion. The commander here is not only tracking the parsimonious budget that XCOM has available, they’re also desperately partitioning it out between all the other major officers as they jostle and argue for their own economic priorities. Every million they give to someone else is a million that can’t be used to shoot down UFOs either in the Earth’s atmosphere or in the orbital vicinity. That latter case falls into the purview of the central officer, who in addition to working the app is also clamouring for money to send satellites into orbit to keep the space-lanes clear of hostiles.

This is XCOM’s call centre

Each role is haemorrhaging money on a regular basis, but to compensate for that each player also has a suite of powers and responsibilities that make certain tasks easier. The research team, through successful research endeavours, will be supplementing this initially meagre assortment of stocking-filler abilities. Every role, through support from the chief scientist, will hopefully be developing a much more extensive set of capabilities with every passing turn. They’ll need it too because things can go from manageable to mangled in a single roll of the dice.

Really though, all of this is fine. It’s genuinely okay – nothing is complicated here. The commander knows what their budget is, and everyone can see how the game state is evolving. If there are three UFOs over Europe, throw two or three interceptors at them. If there are three scary aliens in the base, maybe forget about the relatively optional mission and focus on self-defence. If you have critical tech that needs researched, focus on that and maybe deprioritise the rest. No aliens in orbit? Don’t deploy any satellites there. It’s all fine.

Except it’s not fine, because of all of the allocation has to be done in the timed phase of the game and that’s where the app comes in. I recorded the footage below to show how setup and then a single timed round goes in XCOM. The timed portion repeats round to round, and it begins a minute into the footage. Bear in mind – this is real time and every single role has a person that has to handle the associated responsibilities. If you have four players, this is a challenge of communication. If you have fewer players, it’s also a challenge of dealing with continually divided priorities. Watch the footage, I’ll wait.

Oh. My. God. Right?

When the chief scientist is told new research is available, they draw cards – they don’t get extra time to fumble with numb fingers through a deck that has become recalcitrant and reluctant to obey. They need to draw those cards within the time limit because otherwise it causes problems for everyone else. Then the commander has to collect the budget, and here you can see that early preparation is a super-power something like cheating.

Every diminishing piles of cash are your birthright

If you have a pile of money like this, picking up fourteen of the tokens can easily take more than the time you have available as you make sure you’re not over or underspending your reserves. Sure, these are memory aids more than anything else but you’re going to need that reminder. Everyone is spending your money freely and if you don’t keep track of it there will be problems. Loosely heaped coins – that’s a nightmare. Neatly piling them up into piles of five each though – ah, this becomes a task of a second rather than ten. This is one of a handful of games where stacking your components leads to genuinely measurable gameplay benefits.

Did you get your money, commander? Commander? COME ON COMMANDER HURRY, HURRY.

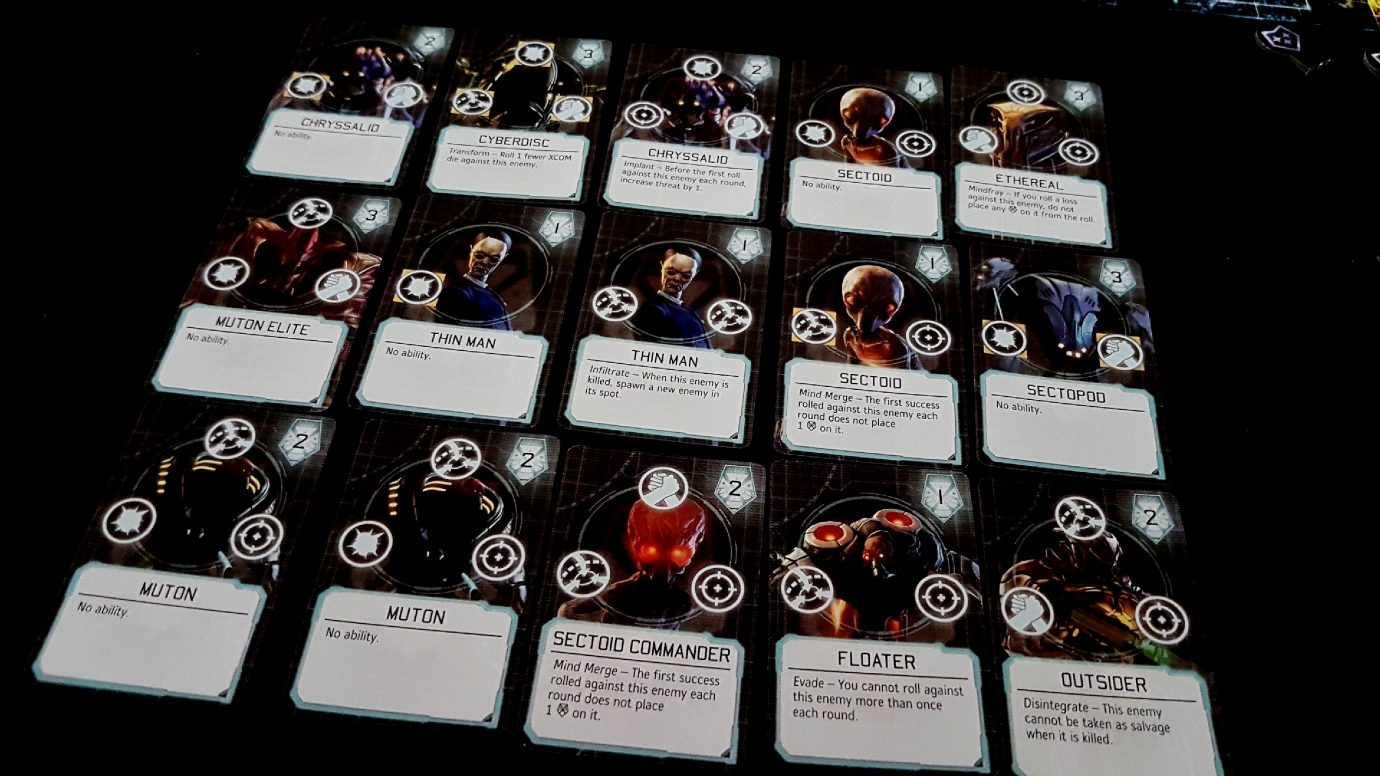

What, aliens in the base? Oh god – so now the Squad commander draws an alien card and places it on the slot available for it, trying to work out what soldiers in reserve might be a good fit for dealing with the encroaching hostile. If the assault is not dealt with, it’ll do damage to the base. If the base is damaged too badly, terrible, awful things start to happen. There’s no point deciding now on allocation though – we’re very early into this process and everyone needs to stay flexible because WAIT NO, chief scientist! Have you had a chance to assess your cards? No? Doesn’t matter – pick one to research. Pick a research team. Assign them. ASSIGN THEM. WHY ARE YOU SO SLOW COME ON, GET IT DONE. No, don’t ask us – just pick something and do it. But don’t do it too much or do it too little because if you screw up we all suffer. I know it makes a difference based on what we’re planning to do but we don’t have time to talk about it just pick something it’ll be FINE GOD because…

Do I even want any of this stuff? I don’t know!

WAIT, NO – Squad leader! It’s your turn – draw two missions, and pick the one that looks like it’ll mess us up the least. What do you mean they’re both impossible? Pick the one that’s least impossible then and work out what soldiers you can send there. I know that depends on the base defense but work something out based on what we can do and what benefit we’d get from it. I know you don’t know what to do. None of us do. The Earth is doomed. Look, if you just…

WAIT, NO – commander! Draw two crisis cards and pick the one that’s least awful. What do you mean they’re both the most awful? Well, one of them is going to happen to us and it’s going to be up to you to decide which it is. Don’t look over there, you don’t have time. What do you mean ‘Sorry, sorry, I’m so sorry’ – that doesn’t inspire us with an awful lot of confidence that you pick…

WAIT, NO! Central officer! UFO’s have been detected! Three of them in Africa. Central Officer? CENTRAL OFFICER! We don’t have time for you to fanny around and… oh right, that’s me. Okay, three UFOs are now in Africa. It’s fine. That’ll be fine. It’ll all be okay because everything is fine.

Commander! Another crisis! Stop blubbering, pick one. Just pick one. I don’t care that they’re both terrible, we don’t have time for this. Don’t whimper, you’re supposed to be the boss here. Pull yourself together, because…

Sorry everyone, this is what your death looks like

SQUAD LEADER! DEPLOY A TEAM TO THE MISSION! I know you don’t know how many more aliens are coming to the base, that’s your problem not mine. Work it out. Just work it out correctly because the commander is looking at the budget with an expression I can only describe as ‘haunted’. It’s easy – all you need to do is look at the icons on the mission, cross reference them with your soldiers to see where they match and where they’re specialised, and then evaluate what you’ll need to defend the base and then assign the soldiers accordingly. You’ve got, like, twenty seconds to do that why are you shaking? No, it’s too late. IT’S ALL TOO LATE because UFOs are detected and… seriously, another two in Africa? Well, Africa – you had a good innings. I’m sure we’ll be able to send reconstruction funds your way after all this is…

CRISIS COMMANDER! ENEMY IN THE BASE, SQUAD LEADER! MORE RESEARCH NEEDS DONE! Emergency funding available commander! No, don’t take it all it has to last us all game. Just take exactly what you’ll need by the time we’re all done with this. Don’t take too little because a budget over-run is monstrously bad for us, and don’t take too much because it’ll just disappear at the end. Just take exactly as much as we need to fund everything and maybe rebuild what gets destroyed. Just take EXACTLY ENOUGH and DEPLOY YOUR INTERCEPTORS IT’S TIME.

What? No, more UFOs might appear. No, you only have eight interceptors in your reserve. No, you can only deploy three to a continent. We all know about Africa, Africa is gone. Africa was nice while it lasted but now it belongs to the red weed. We’ll hold a fundraising concert, but they’re lost. Wait, you’re throwing interceptors there anyway? Well, okay you’re the commander but honestly I think it would just be easier to… why are you calling me racist? I’d let Europe burn too if it looked like that…

Well – that’s exciting

Oh look, more UFOs – in Africa and in America this time. And you didn’t assign any interceptors there, commander. You’re literally the reason Earth is doomed but there’s no time to berate you because it’s time to defend the base, Squad Leader! No, more aliens might turn up. No, I don’t know what kind of aliens. Just… just guess. It’ll be fine, I’m sure. All you need to do is cross reference…

MORE RESEARCH, CHIEF SCIENTIST! HURRY, HURRY!

Time for me to deploy satellites, but there aren’t any UFOs in orbit. I guess one of us is doing well here, right? I’m not going to cost you a penny commander, maybe you should consider a raise or a promotion, ha ha. Ha. Ahem. Seriously, I don’t get paid enough to do this.

CRISIS COMMANDER! ENEMY IN THE BASE! And now we’ve got thirty seconds to use any powers that are timed to try and undo this smorgasbord of absolute arse that we’ve managed to serve up for ourselves. Do your best everyone – move things around, try to undo wasteful allocations, just do it quickly because our time is almost up and now we’ve got to actually try to accomplish some good here or die trying.

It’s only in the resolution stage that anyone gets a chance to breathe because within the timed phase everyone has interleaved responsibilities and decisions that need to be made in the absence of full information. Every time you commit, it’s a compromise – every compromise becomes more intense as time goes by because the consequences of earlier inefficiencies begin to compound. You might want to allocate three interceptors to Africa (sorry, Africa) but whether you can afford to do that depends on what everyone did earlier. The sense of allocating those three interceptors likewise might change as the picture comes a little clearer. Some roles can do a hasty reassignment at the end, or move threats around the board to where they’ll do the least damage. Mostly though you just have to take a great big bite of the shit sandwich you all collaboratively constructed.

Well, that’s discouraging

And it’s in the resolution phase we see the real cruelty in the design of XCOM – in the dice rolls that define success or failure. The dice play in XCOM is one of its most genuinely interesting systems. It gives you a handful of d6s based on the resources you allocated, and sets you to rolling those along with a sinister ‘alien’ die. That alien d8 will result in everything assigned to a task being lost if it exceeds an ever escalating threat level. All those interceptors assigned to Africa? Well, you blew up two UFOs and then the aliens destroyed all three of your planes them. Sorry, they’re not coming back unless you can find the money to rebuild at the end of a turn. All the UFOs left? They increase the panic level in Africa to critical levels. Oh, and the fact Africa is panicking now means they’ll give you less money so – well, good luck reconstructing your air-force on a budget that can barely fund a cheap seat on an Easyjet flight.

Oh look, you assigned four soldiers to the base defence. And you rolled poorly so they’re all dead. Every single one of them is dead, and they also are not coming back. Sorry about that, but never mind – we’re all heading to the grave at one speed or another. By the way, the soldiers you assigned to that mission? They’re also all dead.

Half graveyard, half scrapyard

The only thing though that makes the resolution phase interesting is how inelegantly your resources were allocated during the timed phase – otherwise this is really just a puzzle of maximising reward whilst minimising risk. The problem is – that’s an intensely solveable puzzle because essentially that’s what research is all about – giving people the tools they need to meaningfully bypass the viciously punitive dice rolls in favour of something more reliably deterministic.

A standard EPSRC research grant output

And you can see from the research cards above – they’re not actually very interesting or particularly evocative of the theme. If you use an alloy cannon, you can inflict an automatic point of damage on an enemy where you’ve assigned an assault trooper. The light plasma rifle lets you do the same to an enemy with a support trooper. The plasma sniper rifle does the same for a sniper, and so on. These are tremendously useful powers that let you bypass the risk and consequence that goes with the alien die – but they’re not very exciting. The dice rolling itself, due to the way the threat target increases with every roll, is superb. It’s push your luck at its best, giving you all the control you want over the risks you’re willing to take. It’s collaborative too, because many powers let you reroll or modify the danger and deciding on the utilisation of these limited resources is an act of group decision making. You can decide ‘too rich for my blood’ and bail out, saving your allocated units. Or you can think ‘Well, I’ve still got a one in four chance of not losing everything…’

But all of the progress you make in the game undermines this clever dice system by making it less relevant. The UFO Flight technology for example lets you move dead soldiers to the reserve instead of losing them, which makes the risk of pushing your luck much less intense. UFO tracking lets you add dice to a roll, undercutting the importance of accurate resource allocation. If you’ve built up a technology profile well, you might never need to worry about the dice at all. As such you might feel few concerns at which resources you throw at a problem because you’ve got tech to spend on fixing whatever you did wrong. It seems an odd design choice for progress to gradually neuter the experience that was initially so vibrant and exciting. Doing well in XCOM is a bit like playing a picture reveal puzzle – impossible to begin with, but as a few pieces are peeled away success becomes increasingly inevitable.

The truth is out there

That’s why the app is so critical to XCOM though – it hides a game that is fundamentally, at its core, a bit threadbare. If it weren’t for the artificial tension injected in the timed phase, nobody would be doing anything interesting at all. The app creates a context for scarcity of resources, inefficiencies in allocation, and erratic complication as a result of imperfect information. All of that is intensified through the push of unremitting, merciless pacing. There is a completely analogue interpretation of this philosophy – it’s called Watch the Skies, and it requires far more infrastructure and human management than you can realistically fit into a single cardboard box. The app gives you a neatly packaged version of the escalating trauma associated with a mega-game, and it does that really well.

It’s important here to note though that what I’m describing here isn’t ‘a good part of the game’ and ‘a bad part of the game’, but rather to say that the fun you have in the resolution phase is fundamentally and inextricably dependent on how badly you mess up in the timed phase. The game is forever trying to create circumstances under which you are encouraged, or even forced, to fail. Winning in XCOM, certainly at harder difficulty levels, is a Herculean task. Experience though will dull the danger, because in the end every game is won the same way – by mitigating the risk associated with the dice-play in the resolution phase. That in turn has a corrosive effect on the tension of the timed phases. This isn’t like a crossword puzzle where you solve it and you’re done – there’s far more variety in here than that. It’s more like a Rubik’s Cube where familiarity will make it a far more tractable puzzle than it was when you first took it into your clammy hands.

That in turn leads into one of XCOM’s more structural flaws – your success is dependent on science, and science is dependent on card draws. There aren’t really multiple paths to victory here – there are critical tech cards that are needed to make the risk manageable, and if the risk isn’t manageable all you can really do is ‘roll better’. It’s possible to have a perfectly allocated team that uses the maximum number of dice only to fail and be wiped out on the first roll. From that point on failure in the game as a whole is all but assured. If your science player isn’t getting the cards that are needed, or is failing on the rolls to get them developed at a timely pace, then nobody else really has a lot they can do to stop the invasion. Ironically though, the chief scientist simultaneously has the most critical role and the least stressful job. Scientists don’t even die – they just become exhausted and need a bit of a lie down for a moment. Just like in real life.

The night is dark and full of terrors

For all of this, XCOM at its best is absolutely electric. Seeing your commander apologising wildly in response to a crisis card they just threw in the deck is made all the more entertaining by the fact nobody has time to dwell on it. Everyone has got their own handful of crud to throw into the bubbling stew of the geopolitical situation. It’s simultaneously funny and alarming to see the tight knot of interceptors allocated to a continent uselessly buzz around an empty sky while UFOs gradually seep everywhere else like a deflating flan. Gritting your teeth and rolling the hard six only to succeed and turn the tide of the war – that’s magical. Someone excitedly yelling ‘Oh wow, if I use this ability with this technology we can actually save Australia!’ will be met with cheers. Watching the advance of alien troops into your tender base will be met with a solemn appreciation for the severity of the situation. XCOM has moments of true marvel, and a good session will consist of many of those moments strung together into a real narrative that will stay with everyone. You’ll tattoo each other’s names on your ass cheeks and never feel ashamed, because if anyone had gone through what you all did they’d understand.

The problem is that those sessions aren’t reliable, and you’re just as likely to fall into the valleys on either side of that satisfaction bell curve. You’ll either be faced with an impossible task and told to hold the line, or calmly obliterate alien invaders as if every interceptor was crewed by the Last Starfighter. XCOM is either going to be the most interesting co-operative game you play, or an exercise in shared frustration. It’s also a game that becomes increasingly harder to recommend the fewer players you have – I’m in the relatively rare position of having played it at all player counts (something I can’t always line up for games covered on Meeple Like Us) and it becomes less satisfying as the count gets smaller. It becomes more complicated to play whilst simultaneously becoming shallower in the decisions you make. It also cuts out on the social dynamics of the table and those are based at least in part on everyone having only partial information about how bad the situation is. It works its best at four players, but it also needs four players that understand how the game works because there’s rarely any time to explain unless you want to break the flow of gameplay with repeated pauses to look up information or explain rules.

That leads in to my last significant criticism of the game, which is that the lack of an actual written manual is unforgiveable. The app does a reasonable job of acting as a tutorial to play, but there’s a difference between something which is primarily a teaching aid, and something that is primarily a reference aid. While the app does have help sections threaded through, they’re inconvenient and lack much of the structured ease of browsing and location that comes with a physical manual. For a game that has this many moving parts and this many different roles and responsibilities, it shouldn’t be necessary to rely on the app to find out basic information. Going through the tutorial game for the one player that hasn’t had a chance to play before is far from optimal for the old hands and entirely unsatisfying as a way to learn the game for the other.

So, that’s XCOM – a good game that verges on greatness but falls a little short because you can’t easily bank on having a fun experience. Competence with the game systems all but guarantees that the excitement of the dice-play gets neutered to the point of irrelevance. If the resolution phase were somewhat meatier and players somewhat more involved in the outcome that might be different. As it stands though we can recommend XCOM to many people, but not to everyone. Still, I’ve had a lot of fun with it and it’s entirely possible you might too if the stars align in your favour. Wait, those aren’t stars – they’re starships! COMMANDER, CRISIS ALERT!