Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | XCOM: The Board Game (2015) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.91] |

| BGG Rank | 913 [7.00] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 1-4 (2-4) |

| Designer(s) | Eric M. Lang |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

XCOM is a good game that can be great in the right circumstances. It’s a bit uneven but the frantic pace of the app is the main thing that keeps it interesting – the more sedate resolution phase is a touch lacklustre in comparison to the raw electricity that courses through the timed phase. We gave the game three and a half stars in our review, but we’ve certainly had four star fun with it on occasion.

Accessibility wise this – is going to be a tricky one. The app integration in XCOM has a massive effect on each and every part of the game, but that effect is neither uniformly distributed nor experienced equally by every player. I’ve held off on reviewing this for some time because honestly I didn’t have a clear idea how best to approach the app. In the end I’ve decided ‘something imperfect that exists is better than something perfect that doesn’t’. That is, after all, the entire core philosophy of this site. For the app related work, I am indebted to Hayley Reid – you don’t see a lot from her directly on the site although she’s listed on the About Us page. Over the past two years she’s been involved in my research work on board game accessibility on an occasional basis as a research intern. Over the summer of 2017 she was looking specifically at issues of board game app accessibility, and much of this teardown is drawn from her work.

Hayley has produced a framework for doing focused teardowns of digital board game apps too – don’t be surprised if you see a document focused on the XCOM app alone appearing on the site at some point.

Colour Blindness

This isn’t really a problem although the palette choice isn’t great. Much of the colour scheme emphasises a kind of cool digital blue save for the panic track and base damage markers. These remain possible to distinguish for most categories of colour blindness, although I would have liked to have seen them more effectively differentiated with different patterning as the tokens move into situations of higher escalation.

Panic on the streets of London

Most of the cards don’t use colour as a key element of information, and mostly you won’t be worrying about the cards that belong to other players since you’ve got your own things to be keeping you busy. XCOM dice versus alien dice have a different number of faces, and most of the units you manipulate are unicoloured and of markedly different form factors.

Panic on the streets of Birmingham

The app introduces new problems here because it by itself is a complex piece of moving functionality that has things we need to consider across the board in each teardown category. Palette use though is fine since colour isn’t use as the sole channel of information although it is on occasion a supplementary one (such as when a countdown starts to get a bit too close to zero for anyone’s comfort).

Panic on the App on the Streets of London

Overall, we strongly recommend XCOM in this category.

Visual Accessibility

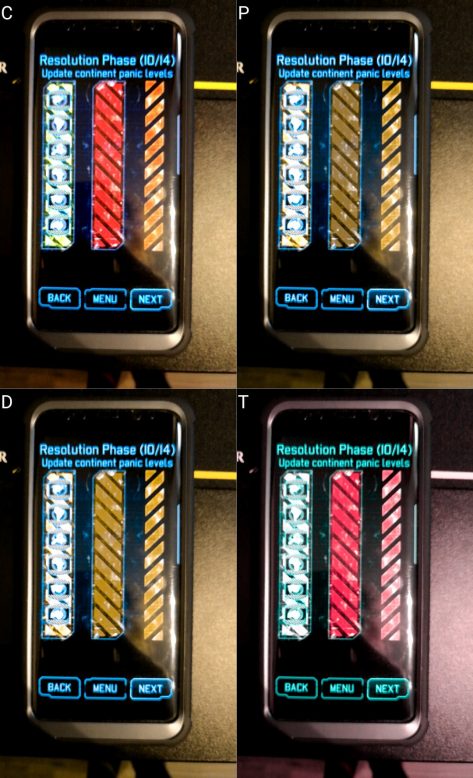

There are lots of issues here, and some of them are relatively baffling. For example, consider the panic trackers for each of the individual countries:

Where is Thunder Child?

Now, it’s fair to say that close up you can certainly tell the difference between South America and Africa, and between Russia, Australia and North America. That is, if they’re all of the same orientation and you have clear, acute vision. Things get rapidly more difficult to differentiate the farther you are away from the tokens (for example, looking at them from the opposite side of the board) and the more interesting the orientations become. This is an issue that could have been easily solved by making use of colour cues to accompany the silhouettes, and that would have notably lowered the accessibility cost that comes from playing a game like this at speed. Sometimes you need to very rapidly identify which country is most at risk of panic and make choices accordingly. That’s not easy to do with these markers.

Really, there’s just panic everywhere

Similarly, the board makes use of a cool blue colour scheme that doesn’t differentiate continents by anything other than geographical familiarity. That doesn’t have much of an impact on the game really, but matching that with a colour scheme for the panic tokens would have made a number of actions in the game less dependent on the starker kinds of visual information. That would have been good, as would using more visually distinctive panic tokens that didn’t rely on being able to tell the difference from a miniature geographical icon. That’s especially true when at the end of a round you need to finger graphical for countries into their appropriate position in the panic level tracker in the app.

Can you tell which one is Africa now?

The app itself doesn’t do much to help in this category either. It oscillates from being text dense (in explanatory sections) or information heavy (in the timed phases). Key information may be contained within small panels (such as budget, or location of UFOs) and this has to be visually acquired quickly and acted upon rapidly. For example, commander budget:

Enough money to do not enough

Or UFOs detected:

But still they come

The issue here for an accessibility teardown is that app accessibility, at least visually, is a problem for the central officer alone. While the app is relatively visually distinct, it’s also the case that it doesn’t support the standard accessibility tools built into the devices with which Hayley tested it. Text to speech wouldn’t be ideal at the best of times for this given the time component, but not supporting it at all means that even baseline, default accessibility isn’t available.

The real-time aspect of the game though is the primary cause of visual inaccessibility. Not only do you often have to make decisions based on what other people have done you need to make them at speed and without being able to inquire as to the game state from other players. Or at least, that’s what’s required of the game as it is meant to be played – there is a pause functionality built into the game but making too liberal use of that is equivalent to simply playing the game turn based in the first place. As discussed in the review, it’s the tension of the timed phases that makes the relatively mediocre resolution sections work. In that respect, XCOM shares a lot of similarities with Galaxy Trucker.

Individual units can be differentiated by touch, which is good, but the exact composition of their skill sets is information available only on a card. That’s something that could be memorized but the problem there is that missions and aliens too make use only of visual information to indicate the troops most able to deal with them. There are only a small number of missions and they could feasibly be committed to memory but both the icon distribution and special effects of aliens is highly variable even within the same alien class. You might face two Sectoids for example and yet find that a soldier is entirely ineffective against one while being the ideal choice for the other.

We’re All Individuals

This means that the Central Officer and Squad Commander are roles that are almost completely visually inaccessible. The Commander is responsible for budgeting and interceptors, and that’s something that could be feasibly handled with only limited access to visual information provided everyone is clear about what they’re doing. The Chief Scientist needs to make research decisions based on maximum group impact and that involves visually parsing the effect of technology cards and then assigning them based on likely budget. That too is not necessarily impossible but likely to be very difficult given the time issues.

So, it might seem that the Commander role at least is one that a visually impaired player could take on – the problem is that many of the technology cards to which the commander might gain access will have an impact on the way other people might play their roles. For example, the Plasma Cannon and many of the geographical powers all require an appreciation of state across the whole game. The availability of these kind of powers is open knowledge to the table, but everyone has their own job to do and as such they may not remember the commander has these powers available during the tight constraints of the timed phase.

And, bear in mind, this all gets more difficult the fewer players there are – the commander role, for someone really willing to make the effort, is the only one we’d be inclined to even perhaps tentatively recommend. Even then, that tentativeness is acute. For everyone else, this isn’t a strong candidate for play. Given all that, overall we strongly recommend players with visual impairments avoid XCOM, and we suspect it is entirely unplayable for those for whom total blindness must be considered.

Cognitive Accessibility

There is very little positive to report here – XCOM is a game that stresses cognitive faculties across the board during the timed phase, and offers few opportunities to recover from mistakes in the resolution phase. We discussed in the review how experienced players will find ways to minimise the effect of the dice through play – that works on the assumption that everything within the timed phase lines up to expectations. There’s some room, in later stages of a successful scenario, to compensate for poor play. There isn’t a lot of give in the mechanics though.

Again, we come back to the problem of timed play in a context of impairment – it’s not a universal rule of thumb, but ‘accessibility requires time’ isn’t a bad heuristic to internalise. It takes time for people with visual impairments to examine game components. It takes time for people with cognitive impairments to make decisions. It takes time for people with physical impairments to manipulate game state. When you throw in a time constraint that is balanced around the idea of relatively abled players you can undoubtedly identify the problem. XCOM requires players to make potentially high consequence decisions, rapidly and without support, and usually with imperfect information. The commander allocates interceptors before all UFOs have been placed. The squad commander assigns soldiers to a mission based on skillsets and mission requirements, knowing that to do so is to divert precious assets from the uncertain state of the base defence. The Central Officer and Chief Scientist have somewhat less imperfect information with which to contend. They still need to be aligning their efforts with what’s good for the group and there is no time, short of pausing the game, to confer. It seems like pausing might be the perfect solution, but I reiterate what I said in the review – this is a game that does not work without the pacing provided by the app. That’s not a trivial concern – fundamentally the game mechanisms only cohere when players are making forced errors in reaction to an unforgiving countdown. Without those forced errors, there’s no tension. Without tension, there’s no fun.

Other problems arise from the expectation of collaborative numeracy (budgeting is very much a group activity – everyone has to weigh up current versus future cost versus benefit) and probability. Knowing how many units to allocate to a task requires a player to work out how many dice they’ll need, how often they’ll likely need them (each die has a one in three chance of rolling a success) and how many successes they need. Again – at speed, and with imperfect information.

The game state too rapidly becomes very complex, and takes into account continental panic levels; base damage; success ratios on missions and research cards; the alien threat (which is adjusted inconsistently depending on the tasks performed); presence of UFOs; availability of satellites and scientists; and so on. The rules too become increasingly complex because new technologies add new options for everyone, and sometimes success comes from utilizing these well in combination. Much of that is done in the resolution phase, but not all of it. Some of these abilities require a good deal of forward planning – sacrificing an interceptor for example as a hedge against poor rolls in the resolution phase. The sense of doing that depends on an ever shifting matrix of needs and probabilities of success versus cost of failure.

And coupled to all of this is that there is a reading level associated with each of the roles as new technology cards are dealt out – the instructions on each are not complex and can be covered in the resolution phase, but they can combine in subtle and non-obvious ways. The more you have too, the more likely you are to forget which is which and what options you have for ensuring success.

Since the game has no manual, only an app, it’s not even as if someone can easily reorient themselves with missed rules or mechanisms. You can query contextual information during the game directly from the app, but more subtle intersections are not likely to be easy to find. You might know how to research a technology, but not what the implications are for that technology being available.

We strongly recommend players avoid XCOM if cognitive accessibility in either the fluid intelligence or memory categories must be considered.

Emotional Accessibility

How much do you enjoy striving in the face of certain failure? Not ‘near certain failure’, but certain ‘impossible to avoid’ failure? How much do you like sitting on the line between those two extremes? How much are you willing to invest on a single die roll – are you prepared to risk everything on a sure thing and have that sure thing fail to materialize? All of that is going to happen during XCOM, and sometimes you won’t be able to do anything about it. XCOM is very challenging, even at relatively low difficulty levels, and failure is far more likely than success until everyone begins to understand its core strategies. Mitigation of risk is fundamentally important, but the ability to do it is dependent on random card draws and successful research rolls. This is a game which is either logically solvable or completely random depending on how lucky everyone gets in early phases.

The timed aspect here adds issues across the board, as it does in many of the other sections. It can be intensely stressful and also very high consequence for mistakes. The app is trying to get you to screw up by throwing horror after horror into your path, and not giving you the information you need to make fully considered decisions. And it’s doing that within time constraints that are intolerant of hesitation. You need to decide quickly, often between roughly equivalent terrible things, and commit fully to your decision. And having done that, you may or may not have tools available to undo mistakes – it depends on how many mistakes have been made by the table as a whole and what technologies have been developed. It’s possible for one bad resolution round to wipe out your entire interceptor fleet, or kill your entire squad of soldiers. That bad round may have nothing to do with you – you might have done everything you could but the alien die killed everyone anyway.

XCOM is a collaborative game, which usually deals neatly with a lot of the emotional issues we tend to discuss in this section. However, here the app adds a new interesting wrinkle – there’s a lot of responsibility on the player controlling the app, and only one person can do it at a time. Failure to communicate key information creates an obvious point of failure, and that in turn creates an obvious target for blame. That’s true for a lot of roles – there’s a lot of blame to go around – but the Central Officer has by far the most pivotal role in distributing key information.

It’s not even as if the app is the only thing likely to raise issues here – the system of ‘draw two cards, pick the one you hate the least’ is great but it does create scenarios where you’re choosing between two terrible things but still taking responsibility for the one you picked. You might end up picking the option that disadvantages one particular player rather than one that causes problems for you. While you are not incentivised to do that by the game (you’re all working together) it might still happen as an accidental or conscious act of decision making. Choosing to destroy two interceptors versus raise panic in a country is a complex weighing up of factors that you don’t have time to fully consider. When you decide ‘Screw it, destroy the planes’ you’ll be judged on what happens as a result rather than what didn’t happen.

As you might expect, we don’t recommend XCOM in this category.

Physical Accessibility

The game has a lot of components, and regardless of which role a player takes there’s a reasonable degree of physical activity. Commanders must reach across the board to distribute interceptors. Squad commanders must draw missions, hand over salvage, and allocate soldiers to the ongoing tasks. The science officer must draw science cards, dole them out to research tracks and lucky recipients, and gather up scientist tokens and distribute them amongst the research tasks. The central officer must work the app and distribute satellites. None of this is especially onerous in and of itself but remember – there’s a time limit on everything. Even simply scooping up coins can be enough for me, a relatively able bodied player, to fall foul of the time limit. To a certain extent this can be mitigated by careful ordering of components but you’ll never be able to eliminate it regardless of role. For those who can reach across the board and manipulate tokens it should be okay. Everyone else might find it more challenging than the time limit would imply.

Those working the app probably have the least reaching across the board to do, but they also have the task of precisely hitting buttons within time constraints and occasionally fingering icons from one part of the screen to the other.

For those that require verbalisation – well, it’s theoretically possible in most cases but practically infeasible. Again, this is due to the time limit and simply down to the fact you don’t have time to ask for things. The pause feature can be used, but this is a common refrain in this teardown – pausing too liberally will undermine every other element of the game. As such, while a player can almost certainly describe what they’d like to be done it’s unlikely anyone involved in playing will have the spare capacity to actually do it.

As such, while XCOM is probably playable with support, the difficulty in providing that support means that we don’t recommend it.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

There’s an interesting feature of the cover here in that while characters are obviously gendered in their physiology, it’s not possible to make out any other identifying features. As such, you can project whatever ethnic or gender characteristics you like and the game doesn’t get in the way of it. That’s not necessarily something I’d endorse in every game, but what you have here is a tabula rasa that can be anything and nothing.

Dramatic

Other pieces of art throughout the game are more obviously representational, and XCOM has a blend of men, women and various ethnicities all shown in positions of power and authority. Generally though the XCOM franchise hasn’t had any serious problems with representation and it’s not surprising to see that carried through into the board-game. That doesn’t mean I’m not pleased to see it though.

The app here adds its own socioeconomic wrinkle in that you do need a digital device to be able to play – however, the specs required are not high and it works on various phones and tablets (iOS and Android at least), and even desktop and laptop platforms. If you don’t have access to a smartphone though this may not be very convenient, but realistically the barrier to using the app is not high. Those that are hold-outs to the shift to digital driven board games though may have philosophical or even logistical reasons that the app or desktop/laptop equivalent is not appropriate.

The price of the XCOM board game is a reasonably eye-watering £55, and while it doesn’t require four players it certainly benefits from a full complement. Technically it can be played as a solo game but I found the experience so intensely frantic that it lacked any kind of fun. Two players are okay (or more than okay if both players are in sync), three is fine, but four is where it absolutely shines. More than that, it requires players with some degree of experience to get the most out of it, and the lack of any written documentation means that fluency in the game systems is not necessarily easy to build. You need the game, and the app, to even learn how it works. That, of course, or any of the online resources provided by the community. Generally though we assess the game as it comes out of the box rather than the game as supported by the generous efforts of other people.

We’ll tentatively recommend XCOM in this category – the representational aspects are good, the app requirements are not onerous, but it’s a lot of money for a game that has a very specific scenario under which it thrives.

Communication

A degree of literacy is required for play, but a more significant requirement is an ongoing ability to either articulate information (if you’re the central officer) or interpret and act upon information you are given. Again, this is within tight time constraints and the information content of discussion will be dense. The app has accompanying music that can be obtrusive, but that can be shut off. However, audio cues such as time running out and the introduction of a new event are useful, perhaps even vital, sources of gameplay information.

Sometimes there will be a need for frantic negotiation, particularly between the commander and other officers, when the budget won’t stretch to the wishes of a player. It might be necessary, to a time limit, to explain why you absolutely need another million dollars to fund a scientist, and why it’s worth sacrificing something else to get it. Similarly scientists might need to consult with other officers to work out what’s best for the team. The only role that doesn’t require any particular consultation is Squad Commander, but that’s also the one with the largest budgetary considerations. Once all the decisions have been taken in the timed phase, the resolution phase allows things to be discussed at leisure – by that point though events have been set in stone and all that’s left to do is see how they resolve.

We don’t recommend XCOM in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

In a very real sense, this section doesn’t matter – we don’t recommend the game in any category that has a significant intersection with any other. The only two categories in which we recommend, even tentatively, are colour blindness and socioeconomic. I can think of no situation where those two are likely to intersect in a way that changes a recommendation in either direction.

The most interesting thing about XCOM really is how broadly the app cuts across every single category of the teardown. It’s such a key feature of the game that nothing is untouched, and in every single one of these it’s the time constraints more than anything else that tanks the ratings. A lot of XCOM is done right, but that doesn’t mean asking people to play very quickly is going to be accessible. It’s important to stress again though that you can pause the app – I’m not discounting that option even though it might look like I am. However, the timed components are important. They’re not optional, they’re fundamental to making this work as a gaming experience. If XCOM had been delivered as a turn based board game it would likely receive a one and a half star review – that’s how critical the time elements are to making this worth playing.

XCOM asks quite a lot of its players – an hour and a half of playtime is what the box suggests and I think that’s accurate. What the box doesn’t fully communicate is how intense those ninety minutes are. Nobody really gets a chance to breathe during the timed phases. The resolution phase has a tendency to drag on too since it’s mostly about dice rolls, and statistically more about what dice other people are rolling. As such, it might be difficult to keep players focused if there are attention impairments to consider. Everyone is deeply immersed in the timed phases, but it’s easy for minds to wander outside of that.

Technically speaking, XCOM cleanly supports players dropping in and out of play, but it’s not a free activity – it’s going to radically alter the play complexity for whoever takes up their role. It’s not possible to safely do this while a timer is running, but responsibilities can be rejigged during the resolution phase. It’s not something I’d necessarily advise, but it’s an option in a push.

Conclusion

Well, it tried its hardest but XCOM hasn’t scooped the title of ‘least accessible game’ on Meeple Like Us. I’m starting to think Blood Bowl will never be bested in that regard. It’s slim praise though – this is a game that, wall to wall, I have little cause to recommend in terms of its accessibility profile.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | A |

| Visual Accessibility | E |

| Fluid Intelligence | E |

| Memory | E |

| Physical Accessibility | D |

| Emotional Accessibility | D |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | C- |

| Communication | D |

We don’t look at a lot of real time games on Meeple Like Us because the design space doesn’t seem to be particularly fruitful – our focus is on the BGG Top 500, and as best I can recall the only real time games we’ve looked at before are Escape: Curse of the Temple and Magic Maze. Escape received a less than complimentary teardown and Magic Maze likewise got fairly kicked around in our analysis. No matter what you ask someone to do, it’s harder when you make them do it against the clock. I’d say XCOM was a continuation of that design lesson but it’s hard to justify that claim when we only have three data points. At least, for now – there are other games on my shelves that will give us a chance to explore this more deeply.

We liked XCOM enough to give it three and a half stars in our review noting that at its best it generates considerably more entertainment than that rating would suggest. Its unreliability as an engine of fun though means you’re as likely to crash and burn without any chance for success as you are to engage in a fraught and meaningfully balanced battle with otherworldy foes. Our recommendation too has to be tempered with the knowledge that very few people with accessibility concerns will be able to enjoy it to the fullest. That’s a shame, because it’s an exciting game with an excellent licence and I would have been much happier if a broader audience had a chance to experience the failure curve that I and others have happily explored.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.