| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Pit Crew (2017) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Light [1.20] |

| BGG Rank | 5365 [6.41] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 2-9 (2-6, 6) |

| Designer(s) | Geoff Engelstein |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Error: No such teardown

I’ve never really fully understood why people enjoy watching car races. The whole thing has always struck me as little more than queueing at speed. Everyone is driving around a track at velocities so high that when you see the event up and close it manifests itself as little more than a blur against the horizon accompanied by the sound of a wasp’s nest gearing up for war. The whole thing exudes a kind of anti-fun aura. Despite this, a significant proportion of the population loves it. Millions get poured into this sport – that is, if it even counts as a sport. I suspect my even querying its status in that respect might have made some people sit bolt upright in their chairs. If you’re currently furiously typing a passionate defence of the sporting credentials of racing could I ask you direct all such correspondence to the special email address I set up for the purpose?

The best I’ve had it explained to me is that it’s not about the race, it’s about everything that goes into the race. It’s about the technical specifications and innovation needed to eke out an advantage on the bleeding edge of human engineering. It’s about the battle of mere mortals against the unrelenting, uncaring indifference of physics. It’s about the subtle poetry to be found in tracing out the recalcitrance of a drag co-efficient and taming it like a wild stallion. It’s about mastering aerodynamics and working out where the sweetest point is to be found between speed, braking, manoeuvrability, and the track in front of the driver. That perspective at least gives me somewhere to dig in my fingers to get a grip on the whole baffling mess, but it’s still not enough to get me invested. I’m more interested in stories about humans, not stories about equations. Racing just doesn’t generate the kind of stories that draw me in.

I keep typing this as ‘Pirate Crew’ and the correction always makes me a little sad

Pit Crew though is a game about perhaps the most intimately human element of the whole system. The attention of this box is lavished on the poor, largely forgotten sods who actually make sure the car stays in one piece over the course of the race. Whenever I’ve watched racing, and it’s admittedly infrequently, the most mesmerising part of the whole thing is the pit stop. It’s almost magical how a car will zoom in from the track, park for a few short seconds, and head off back into the race with a fresh set of tyres, a rebuilt engine, new fuzzy cubes hanging from the rear view mirror, and a recharged air freshener. From the outside it looks like someone half-arsed the animation on a computer game and erroneously left the whole thing sped up beyond all believability. And yet, it actually happens – it’s like real life played in front of you on fast forward. It’s ironic really – the most interesting part of the whole thing is when the race briefly pauses.

That’s where I find the value in racing – in the miracle of synchronicity and skill that is hidden away from the glitz and glamour of the race itself. If anyone was going to make an HBO TV series about racing, I would want it to have its sole and irrevocable focus here. That’s exactly what you get with Pit Crew. I mean, sure – you get the race and the race-track too. It’s given the exact amount of attention you’d reserve for the background details in a home video staged for You’ve Got Framed. The race is there, but it’s just your score. The race-track is where you’re going to chart the success, or failure, or your maintenance endeavours.

Le Mans

Your focus as a player is elsewhere. It’s on the car that comes speeding into the pit stop ready for you to do your business. It screeches to a halt, and it’s your job to turn the hand of cards you have been dealt into well executed, competent repairs. Each round the wear on the car increases and the task of repairing it gets a little more difficult. To begin with, you just have to deal with the tyres and the fuel. Increasingly as the game goes on you need to also invest additional time tending the engine. Regardless of what round you’re in, the job is basically the same – ‘meet the requirements of the car body with the tools you have in front of you’

This can’t be my car – it looks roadworthy

Look at our car here – four tyres need replaced, and the fuel needs topped up. To replace a tyre we lay down cards in an unbroken sequence that starts one removed from the number at the wheel. For the top right wheel (6) we could play a five or an seven, And then we need to play a card one removed from the one we played until we have four cards correctly laid down. At that point we place one of our ‘cap’ cards on top of the pile and can focus on the rest of the car. For the fuel tank we need to lay down cards that sum up to the number shown on the top – 27 in this case. When we’re done with all of the necessary parts, the car zooms off and we work out how well we scored.

Spanners, hammers, welding rigs – the whole set

We have a hand limit of six cards, and while we can draw cards whenever we like we can’t ever exceed that limit. We need to play cards out before we can draw more in, but the exact relationship between playing and drawing is up to us. We can also discard cards, but doing that too freely will penalise us when it comes time to calculate progress. We want to discard as sparingly as possible as a result. That means you’re constantly fighting between what you need and the limits within which you can obtain it. Every discard is permanent within a round of the game, and the value of any individual card is defined only by the car in front of you. The card that is useless now might be vital in a few seconds.

But we’re professional car…fix… people. Car fix meeple? Maybe we’d begin by playing two cards down for the top right tyre:

Nothing but Michelin for us

We could then draw two fresh new cards that might be better for what we’re attempting to do. We can work on parts in isolation, or in parallel, or in whatever combination we like. Given the nature of the decks, you’re almost always going to be dividing your attention up where the cards are going to be at their optimal impact. The problem is, optimality is a shifting proposition that ebbs and flows with the cards we draw. What seemed like the obvious choice with one set of cards might become radically different when a few have been played or drawn.

It’s all going so well.

Your cards are either black or white, and while they can be used interchangeably you’ll want to address one component with a single colour if you can. Uniformity of assignment gives you a turbo boost during scoring, and that’s the only way you can move your card forwards. Your minimum level of success here is ‘don’t screw up’, but that’s not the philosophy of a pit crew. This isn’t a job for those looking for a merely passing grade. This is a job for those seeking to get the A on their job performance review. Not breaking the car isn’t enough.

Done!

Once a card is laid down, it’s there for the duration of the pit stop. You can’t remove it, or move it around, or do anything except come to terms with its presence. As such, as your deck dwindles down to a sliver you’ll likely find yourself having to make compromises. The cards you needed now were discarded earlier. The turbo boost you banked on is now impossible. You’ve got exactly the card you need, but you need that one card for three parts of the car and only one can get it. As time goes on, your options whittle away and it becomes harder and harder to feel genuinely satisfied when you mark something as finished.

Capping off

Gradually though you’ll get to the stage the car is ready to go – everything will be capped off, and the task is done. If you’ve done well, your team will progress around the race-track. If you’ve done poorly, well – they won’t. Every part of the car you screwed up generates penalty points, and each penalty point moves every one of your opponents further around the track. Don’t screw up.

Once everyone is done with their pit crew duties, an audit of the work begins. Taking each component in turn, you make sure the cards you laid down meet the requirement for repairs. You’ll spread out your tyre and make sure that it follows the appropriate sequence, and confirm any turbo boosts you are due. If you made a mistake, you’ll honour your penalties by giving motion to your opponents. It can be galling if all you manage to do in a round is accelerate everyone else around the track, but you might just have to make your peace with that possibility.

Vroooom

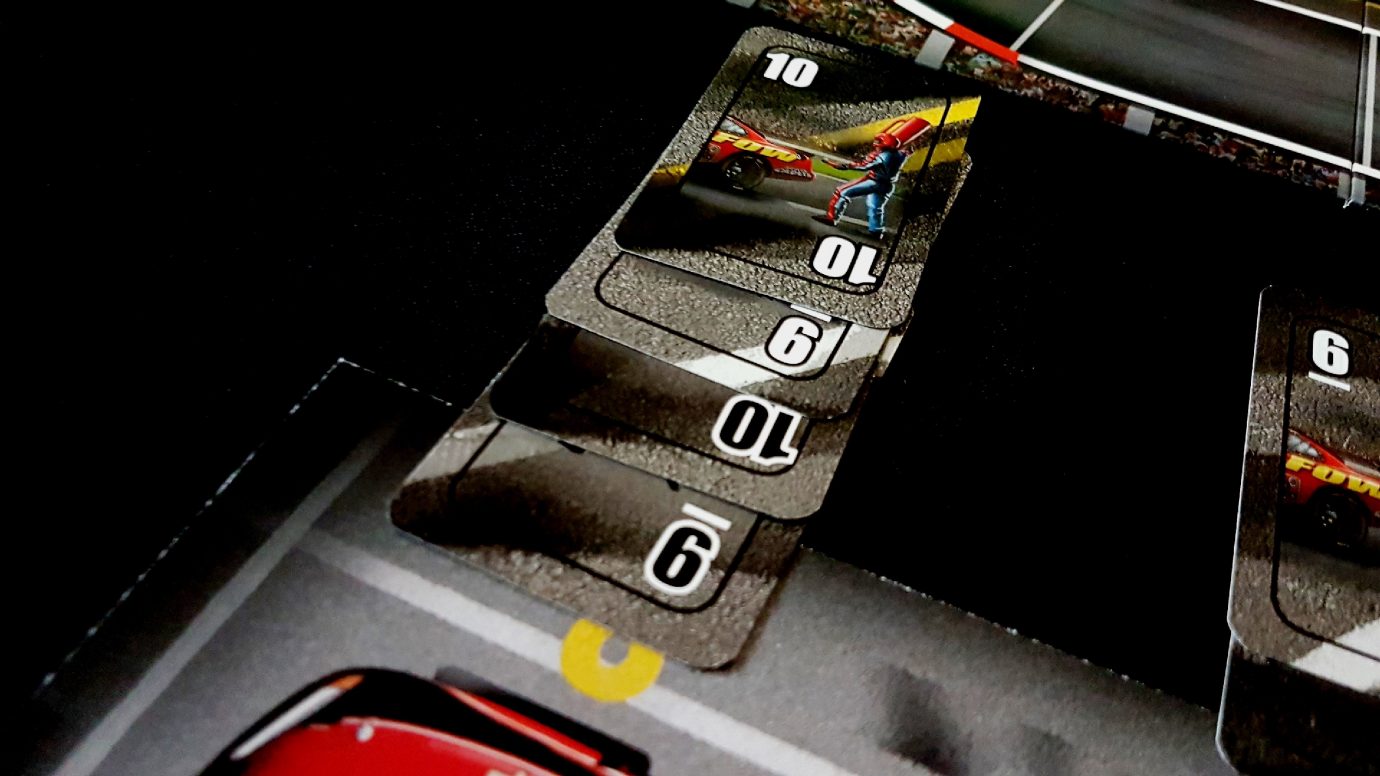

As an example of how an audit might work, check the image above. We begin with a fixed six, then five, then six, then seven, then eight, then capped. A perfect tyre, all of the same colour – no penalty, and a turbo boost. VROOOM, we move our way around the track and then move on to the next component. At the end of this process your car lies dissected on the table like it were a Transformer being subjected to an invasive autopsy by an unqualified engineer.

‘It was like this when we found it, officer’

If you accrue eight or more penalty points in a round, your car spins off and crashes. You’re out of the game when that happens. But if you’ve done well, such as in the round above, you’ll find yourself zooming happily around the track and hopefully ahead of your opponents. Once you’ve done this three times, the game is over and the winner is the one that is farthest ahead.

Hit the accelerator

Pretty exciting stuff, eh? You lay down your cards, you try to make sure they’re optimally assigned, and then you race around a track depending on how well you do. You seem underwhelmed though and I’m not sure why – surely you can see why this is going to be something that gets your heart racing with every misplaced card and every broken car part?

No?

Wait, hang on. Let me check back to see what I’ve missed in the explanation.

Oh yes, sorry I forgot to mention this earlier. This is all done in real time and as fast as you can possibly do it.

You’re not sedately partitioning out cards according to some internal optimisation algorithm. You’re throwing these cards desperately onto the car at speed, and without a clear idea of what time you’ve got available to finish. In a real world race, the constraint is ‘be faster than your opponents’. That’s what it is here. You want to get your car ready to go, but you also want to do it first and sometimes that’s going to involve trade-offs. It’s almost certainly also going to involve a degree of barely directed panic. Your car autopsy isn’t going to be conducted on the incorruptible corpse of a saint – it’s not going to look like the one above. Your autopsy will be far more undignified, like this:

‘We dragged this one out of the river’

I mean, look at this thing – it has to deal with an engine, and that needs a pair (and later two pairs, and then three pairs). That’s fine – it’s hard to screw that up. But the top left tyre begins with a six because someone thought it was a nine. The bottom right has two fours played together. The fuel tank sums up to 32 because whoever was stuffing the cards in there lost count and considerably overshot the target. Often you’ll have put too many cards in for a tyre. Or not enough. Or just sacrificed your chance at motion with mixing black and white cards too liberally and too freely. This car earns two turbo points for the engine, and awards six points of movement to each opponent in penalties. That’s what Pit Crew ends up being. Yours is not the autopsy of a healthy jogger unaccountably dead in their prime. Your gruesome task is to dissect the victim of Gluttony in the movie Seven, and there is literally no value to be found in the organs being merrily scooped out of your cadaver.

You might think ‘Well, I’ll just keep a cool head and everything will be fine’. Sometimes that’s even true! But in order to keep the wheels turning you often need to discard cards because nothing you have fulfils a need in front of you. Even if you have the number you want, you usually also need it in a specific colour. As a consequence of that you’ll start throwing cards away in the hope of a more fortunate draw, and those cards are gone – you can’t get them back. You might be hoping to draw a card that’s already been thrown away. You might consider sacrificing your chance to make guaranteed suboptimal progress in exchange for uncertain optimality. Sure, keep your head. Work the problem. The enemy here is your own panic. But as long as you can control that, you’re going to be fi…

The starter pistol

Wait, did you hear that? Did you hear someone rolling a die? I hope not, because that’s about as tangible a way as possible to be told that you’ve left it too late. After a car is complete, and before the audit is performed, every team that is done can grab a dice and start rolling it as fast as they possibly can. Every time a six is rolled, they get to move their car a space forward. It’s amazing the amount of stress the sound of rolling dice can trigger when you’re looking at a car that’s still stripped down to its nuts and bolts and with no end to the surgery in sight. Roll. I need a two. Roll. And a black eight. Roll. Discard everything! Roll. Oh no I’ve made it all worse! Roll…

Sounds a bit more interesting now, right? It’s like a kind of weird love-child between Galaxy Trucker and Lost Cities, merged with some genuinely effective psychology and push your luck. Maybe finishing a car now with mixed numbers is worth it if you get a few more seconds of dice rolling – but good grief you can roll that die a dozen times and not move a single space. At what point is it sensible to sacrifice the guaranteed progress of a turbo boost, assuming it’s even possible, for the gamble of the bones? Is it worth even giving up on a component in the hope you make up the difference? Or perhaps you’re hoping to claw back a few spaces with a kind of Shock and Awe campaign. The rattle of a single rolling die ramps up the tension, and thus the mistakes, of every other player. If two of you are busy doing that, well…

‘If only we had a tyre that started with four’

BUT WAIT THERE’S MORE!

What we’ve been talking about here is the single person crew game – that’s what you get for two or three players. There are three different colours of car in the game, and the game goes up to nine players. Nine. NINE. The only way it can do that is by having pit crews of more than one person, and that’s when the design of Pit Crew reaches its apotheosis. It’s absolutely at its best when you and everyone else on your team has only a subset of the cards available. It’s most well expressed as a game when you need to co-ordinate these hands against the parts of the car against the time limit and against your own disagreements as to optimisation. In a two player crew, you each have three cards. In a three player crew you have two. You’ve still got the same number of components to repair, you’ve just added a buttload of additional co-ordination on top of it. The crew that communicates best and most clearly will find things much easier than the crew with the wild maverick that starts throwing cards everywhere in blind panic. That latter crew usually has me on it, which I’m sure is probably just a co-incidence.

BUT WE’RE STILL NOT DONE!

At the end of every round, monkey wrench cards are dealt out – one for each team. Starting with the team in last place, these cards are selected and added to the toolkit for the crew. Sometimes they’re useful to you – wild cards, or modifiers that change the risk and reward of particular activities. Sometimes they sabotage an opponent – forcing them to have smaller hand limits, or requiring them to make a sequence of five cards instead of four on a single tyre. Sometimes you’ll take them just because you don’t want them aimed at you. Other times they’ll be the difference between success and failure. Some of them are very useful – useful enough to completely change the way you approach the game.

An exciting range of upsetting things

The Crew Chief, as an example, halves the penalty points from discards. With that, you can be a lot more laissez-faire about what you give up. If you also have access to the Veteran Crew (two crew members have their hand limit increased by one) then you’ll find you can afford to be a good deal more contemplative about how you approach the task. You’re much less likely to be stressed into failure because your options are much wider. On the other hand, the Veteran Driver card means you move your car forward on a five or six of the die roll. As such it becomes a much better prospect to finish your pit actions earlier even if you have to do an inferior job to make it happen. Sabotage inflicts a penalty point every time your opposing teams add a nine or a ten to their fuel tank, which means they’ll likely burn through more cards to meet its requirements. In the process, they’ll use up cards that perhaps would have been much more valuable in other parts of the car.

It’s an exciting game that becomes more exciting the more points of failure get introduced. Two player Pit Crew is fine, if a bit sterile. The more teams you add, the better it becomes. The more people on each team, the better it is. The more frantic and chaotic the action becomes, the more intense you’ll find every round. It’s very good, verging on genuinely great.

The thing is…

Look, mostly I discuss components and the like in the accessibility teardown because they rarely have a direct bearing on the game design elements we address in the review. I dithered quite a lot over the rating I was planning to give to Pit Crew, and it kept coming back to one simple thing – the cards suck, and in that sucking they take some of the fun with them.

So smol

Like pouring petrol into a diesel engine, the cards here are so small and so pokey that they cause the whole thing to aggressively stutter and splutter. It doesn’t quite ruin the game, but it adds a thin veneer of clunky unpleasantness to everything you do. They’re difficult to shuffle, which is an important part of between round preparations. They’re difficult to draw from the deck, coming into your hand with all the oily insouciance of a strip of velcro. They’re difficult to pick up if you drop them, and you will. They have a tendency to stick together, which is the last thing you want in a game that’s about very, very quickly placing them exactly where they should go. And they’re tiny. Like – insultingly tiny. I appreciate full size poker cards would have had an impact on how much space the game took to play but they also would have made it meaningfully, tangibly better. I like playing Pit Crew, but I don’t like it as much as I could because the cards that are the focus of your experience are terrible in every respect.

The best kind of real time games add tension through diminishing options. They do it through layering more and more things to worry about and giving you fewer and fewer tools with which to accomplish any of them. The worst kind of real time games add tension through physical frustration, and the cards add a layer of that to every single thing you do in Pit Crew. Stress and tension makes it difficult to physically manipulate components and that’s part of the fun – but the game has to meet you half way here or it tips from enjoyably infuriating into genuinely aggravating. Everything is harder to do because of the cards, and none of it is harder in a way that improves the experience.

It all looks and feels very cheap – penny pinching, even. I can look beyond that in most games, but it has gameplay impact here that can’t be ignored. The impression of cheapness carries through to everything, including the mats you use for the cars. These are adorned with advertisements for other games. Depending on your frame of mind that might come across as a clever nod to the ubiquitous advertising to be found in NASCAR. Or it might equally be seen as a crass attempt to get direct targeted marketing to you in a way that bypasses your ad-blocker. In a game that was more generous in its components I’d assume the former. Here, I’m not so sure. It just feels classless.

I don’t like ending on a downer like this, but it is a shame that a game that could have been genuinely great is so badly let down by a pathologically cheapskate approach to its components and aesthetic design. If you can look, and feel, your way past that you’ll certainly find Pit Crew to be a wonderfully electric experience. If not – well, I can’t exactly blame you. It’s one of the reasons as to why I’ll sometimes make excuses to not play it.