| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Trial by Trolley (2020) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Light [1.03] |

| BGG Rank | 4308 [6.08] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 3-13 (3-11) |

| Designer(s) | Scott Houser |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

I have more party games on my shelves than I have been invited to actual parties in my life.

Two. I have two party games on my shelves.

Despite being a social train-wreck, I still have opinions on what makes a good party game. Mostly those opinions are ‘Buddy, come on. Nobody is here to get their cardboard on’. Beyond that though there are aspects of design, theme, approachability and mechanisms that are important to nail if you aren’t going to ruin a disproportionate number of evenings. Suffice to say then that I was somewhat surprised to find a game of moral philosophy, from the makers of Joking Hazard, pitching itself as a option for your night. Let’s talk about Trial by Trolley. Or, as it so obviously is, Unlicenced ‘The Good Place’ Game #1.

The first question that Trial by Trolley presents to us is the one we addressed in our review of Joking Hazard – ‘where’s the game here?’. I don’t mean that in the usual snotty sense of ‘Pshaw, this is a mere activity and no game, no game this’. I mean literally ‘Where do you find the game?’. Some games exist in their components. You see that in Kickstarter campaigns where you’re obviously buying miniatures with some vague rules attached. Some games exist in their rules, where the cleverness of their mechanisms is in ascendence and everything else fades away. No Thanks, Skull, Chess – all of those games are just as good if you play with official components, match-sticks or damp beer coasters. Some games though don’t really exist in either – they exist only in their execution. Sure, they might have content but the actual spark of fun is only animated by social context. That’s where party games tend to live. The game is a catalyst to turn your friends into board game components.

I’ve had actual dreams like that.

It’s an important point because these games live, or die, not on their design but on the use to which their players put them.

There’s a particular form factor that party games tend to take in terms of their boxes. They are suspiciously long, for one thing. That’s because many of them take exactly the same approach to component design – massive, endless stacks of cards filled with ludicrous variation. They too matter only insofar as they give you things to talk and argue and debate about. Mostly the intentions are grounded in pragmatic reality – ‘You like your friends, surely, so what better way to have fun of an evening than make them laugh. Let’s help you with that’. Cards Against Humanity, Joking Hazard, Funemployed, Time’s Up – they’re all just delivery vehicles for comedy and they live and die on the basis of how well your friends react to what you serve up. This form factor then tells you something – there isn’t a game in the box. What’s in the box is the toolkit for getting the game out of your friends. And, unfortunately, not all toolkits work equally well in all scenarios.

Trial by Trolley is both exactly the same game as all of those mentioned previous, and yet something entirely different. It’s a game of comedy to be sure, but it’s also a comedy of a potentially more elevating nature. When games like Cards Against Humanity skirt against issues of utilitarianism, existentialism or moral precarity it is an organic accident – mostly a consequence of who is playing and a quirk of serendipitous juxtaposition. Someone plays a card, it receives an answer, and the result is of sufficient insight that it gives everyone an unexpected reason to pause and briefly contemplate. In moments like this, it’s transcendent – in the literal sense, the response everyone has to what has happened goes well beyond anything the game is designed to accomplish. It’s rarely something you experience because the subject matter is rarely fertile ground to brith the seeds of reflection. Trial by Trolley though has as its soil a richer loam.

So, here’s how the game works.

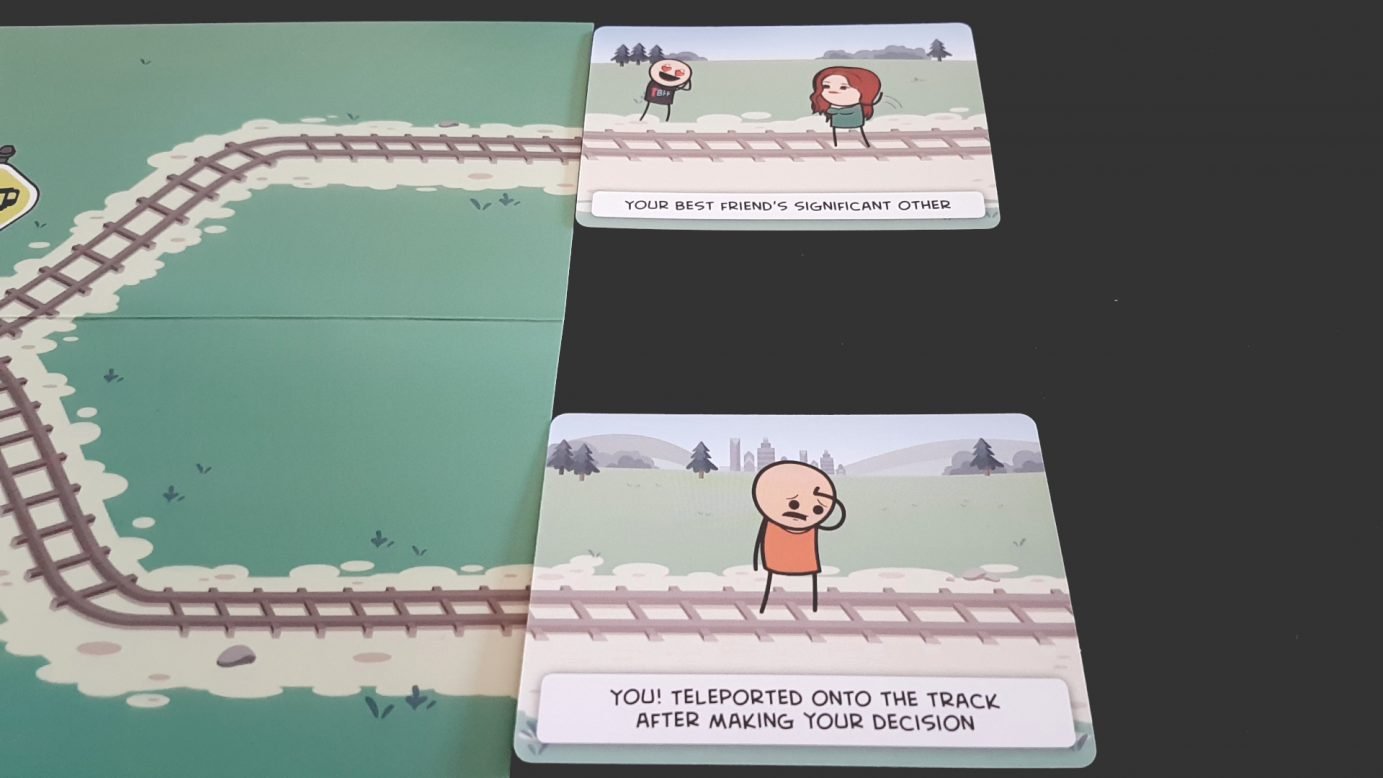

Two teams each take ownership of a particular track of a railroad. A train is coming, and it has only one thing it can do – take track A, or track B. It can’t slow down, it can’t stop. That train is rolling through no matter what happens. A random card is dealt out to each track, indicating an ‘innocent’ victim that just so happens to be standing in the way of the train.

Each team then looks at their hand of cards, and adds a second ‘innocent’ person to raise the moral consequence of the conductor taking their track.

And then each team takes a ‘guilty’ card and places it on their opponent’s track, attempting to balance the cosmic scales with a little metaphorical vaudeville musical flourish at the end of the slaughter to come. ‘Sure, you took out the scientist that was about to invent a cure for cancer, but at least you also killed the guy that invented microtransactions. Fifty fifty, innit’.

Finally each team then plays a modifier card from their hand, and this can go on any card on any track, but also importantly on anything depicted on any card. It adds a little ‘one last thing’ detail to the scenario that might intensify or nullify the situation.

Once this is all done, the decision on who is to live and who is to die is up to the third team – the conductors who must decide onto which track they are sending their runaway train. This they do with the assistance of the other teams who will argue for the scenarios that have been constructed. Anything goes here, like in most party games. Your job is to convince, and that doesn’t necessarily always require rational debate. You have a full rhetorical toolkit available to you. Success can come as easily from a plea for clemency as it can from successfully advancing the case that cancer isn’t all that bad, ecologically speaking.

It’s a smart premise, and one that appeals a lot on an instinctual basis. Its mechanical simplifications, with regards to the trolley problem, are forgivable. It’s the simplest form of that thought exercise, and that’s understandable. Requiring every player to have an advanced grasp of ethical dilemmas would make this a very unapproachable game. Here, it’s judgements all the way down with no need to wrestle them into an intellectual framework. No sublety, no nuance, and importantly no blame. This isn’t a game about working out the right thing to do, but rather the most entertaining thing to do. It’s utilitarianism as a blood sport.

Does it work though?

Sort of.

Look, Trial by Trolley clearly accomplishes what it is intending to do – gamifying an ethical dilemma in a way that generates a passable sense of fun. It perhaps doesn’t have much in the way of longevity of an evening, but it’s no worse in that respect than any other game of this kind. The indulgence of the table is worn away a little by every successive round but really you get to stop whenever some consensual threshold of boredom has been passed. It’ll never outstay its welcome because active, enthusiastic participation is what drives the desire to play another round. When that disappears, then it naturally suggests for itself the time to quit.

Does it work better than your other alternatives though? That’s a harder question to answer and it’s going to depend on the people with which you are playing. I suspect that Trial by Trolley is in this respect hoist by its own petard. Some people will be much more likely to be invested in this over, say, Funemployed. They’ll also be the ones that are least likely to actually find the fun in the premise because of the limitations in its design. Everyone else is probably going to find more fun in a game that doesn’t look so suspiciously like homework from your Ethics 101 class. If they give it a go though they’ll find it’s just as funny as all their other choices, and gives a chance for the comedy to explore territory that the others only incidentally reference. You’re not going to find conversations in Funemployed are often going to include oblique references to Plato’s theory of forms. Joking Hazard rarely touches upon nihilism as a gameplay gambit. You don’t need to be able to talk literately about philosophy to play Trial by Trolley, and people may be pleasant surprised by how sophisticated their informal understand of morality is when it is put to the test.

The review can end here really. If you’re in it for fun, it’s a good candidate. Better than Cards against Humanity, on a par with Joking Hazard, not as good as Funemployed. Job done. If you’re in it for philosophy though, move on. This place is not a place of honor. No highly esteemed deed is commemorated here. Nothing valued is here.

The rest of the review has little bearing on Trial by Trolley specifically, so feel free to skip it. It is the definition of over-thinking.

The flaws in Trial by Trolley are not of its own design. The simple truth is that board games (and video games) are terrible vehicles for exploring ethical dilemmas. Everything in the way they work is almost diametrically opposed to what’s needed to provoke or assess meaningful decision making.

- They are highly formalised systems, with fixed rules and often fixed scoring

- Their rule systems will, as a natural consequence, embed the biases of their designers

- They are morally discontinuous spaces where the normal rules of society do not pertain

- The need for a game to balance ensures that all strategies, ethical or otherwise, must be roughly equally viable.

- Philosophical messaging is either so ideologically prominent that it skews perceptions, or so invisible that it mandates subjective interpretation.

There are games that do skirt with some meaningful conception of ethical reflection. The first one that anyone reading this blog is likely to raise is Brenda Romero’s ‘Train’. Secret Hitler could be argued to have some merit in terms of sociological storytelling. Holding On manages to convincingly navigate troubling territory with its design. None of those games are free of the problems outlined above though. The messaging they contain, I contend, would have been more effective in any other medium. That they work at all is what’s remarkable. Similarly for video games. Spec Ops: The Line and Papers Please are two that engage in a meaningful sense with ethical decision making but they are notable exactly because of how unusual it is to be successful in that arena.

Those limitations are exactly what makes this game frustrating for someone interested in moral philosophy or ethical decision making because all those confounding factors remove the really interesting insights the premise could have generated. None of the scenarios have any real insight in them – they can’t, because the deal is random. The scales are inherently unbalanced and even if they weren’t you’d never be able to compensate for all the other factors that are threaded through the design of a board game or a video game. The medium is the message, as Marshall McLuhan said. The truth is that some messages don’t thrive at all in some mediums.

But even that isn’t the big problem with the game.

If you’re interested in moral philosophy, you come to this game with an opinion you can relatively easily articulate to others that are interested. You can draw a circle around your conceptions of right and wrong and everyone will know, within acceptable parameters, how you are likely to respond to each of the scenarios.

For example, I am a moral relativist. In the absence of a fixed point of universal moral conception (like God), all moral judgements must be relative to all others. There is no such thing as universal right or universal wrong. No such thing as universal good or universal evil. All decisions are contextual, all justifications driven by nothing more than rationality. And in that, I hold to Kant’s conception of the universal law – in order for any behaviour to be truly ethical, it must be something to which all people, at all times, can adhere. Importantly though I am also hugely influenced by a kind of nihilism tempered by Camus and his ideas around cosmic absurdity. There is no meaning in the universe. All meaning is personal, temporary, and subjective. That which we do is inherently absurd, and our only destiny is obscurity. There is no meaning to life. There is only what meaning we can carve for ourselves in the briefest flicker of candlelight represented by our consciousness in an endless, uncaring universe.

Bleak, right? You’re not kidding. It’s all I can do to stop screaming in the mornings.

It’s enough though that in a game like Trial by Trolley my choices are so codified as to be predictable by an algorithm. And when they aren’t, you could certainly convince me by leaning into my intellectual preferences. I’m deontological as opposed to consequentialist, and you can wield that like a weapon if you know what magical incantation to intone as your argument.

So if you’re at a table with a bunch of moral philosophy professors (everyone hates moral philosophy professors) then Trial by Trolley is an exercise in futile argumentation – you’d get as much out of it as you would from a random news article in a random newspaper.

Or, in simpler terms, if your moral position is that you look to minimise harm at all times then that is exploitable. There’s no point playing a card that says ‘Your current crush’ if the other track has ‘A bunch of high school kids on a trip’. The principle of minimal harm has already decided who is getting hit by the train and the discussion that would follow is futile.

Really, there is only one thing worse than playing Trial by Trolley with a group made up of the kind of people that would be excited by replaying the trolley problem over and over. It’s playing with a group of people partially made up with the kind of people that would be excited by replaying the trolley problem over and over.

I kept that discussion away from the review proper because I think it’s an issue that exists in a particular kind of player rather than the game itself. Trial by Trolley does nothing to present itself as a serious tool for exploring moral consequence. It does everything to present itself as a fun party game. That it doesn’t work well in a scenario where it is not claiming applicability is not a flaw. But… the potential for it to excel in that scenario is the only reason I bought it. I didn’t expect it to be revelatory, but I did hope it might lend a certain additional cerebration to the tired party game format. And it does, to a degree, but I can’t say I really learned anything about my friends in the process.

Oh, I just looked again. I only have one party game on my shelves at this very moment.

Still more than the number of parties to which I have been invited.