Recently I participated in the Axschat hour hosted by Debra Ruh, Neil Miliken and Atonio Santos. It was a lot of fun, albeit fun at speed. There were lots of discussions and plenty of interesting insights but they were all delivered with the intensity of a heart-stopping dose of heroin. At the end of it I was physically wrung out and all jangly like my synapses were on fire. There was so much to talk about, and so many people talking.

There were six questions that were raised by the hosts during the hour, and they were each interesting enough I think to warrant editorials of their own. The one that has stuck with me though was the second question:

Are there common accessibility issues across board games despite the fact that every board game is different?

One of the themes of the work we do on Meeple Like Us is that each game is its own unique accessibility puzzle. The rules, the components, the social context and the aesthetics all come together in combinations as unique as snowflakes. Even games that seem very similar (say…. Funemployed and Cards Against Humanity) have very different accessibility profiles because of the nuanced way all these elements interrelate. Two games looking like they play same way usually means nothing except the accessibility teardowns will be surprising.

My instant, gut-feeling answer was ‘there are common problems but there is there is no inaccessibility shared by every board game’.

Luckily, I got these questions ahead of the Axschat hour because I was sort of the ‘guest of honour’ – I’d been invited to chat with them for their Youtube channel and this was the followup discussion about the issues we’d raised and debated. I prepped a version of my gut-feeling answer, but then I started to think a little bit deeper.

And you know what? I was wrong.

There is no shared interface to a board game – some things are very common but nothing is truly ubiquitous. Some games make no meaningful use of colours. Some have no cards. Some have no dice. Some have no board. Some don’t have any graphics, or use graphics rather than text. There is nothing that links board games together in a way that gives you anything on which you can rely.

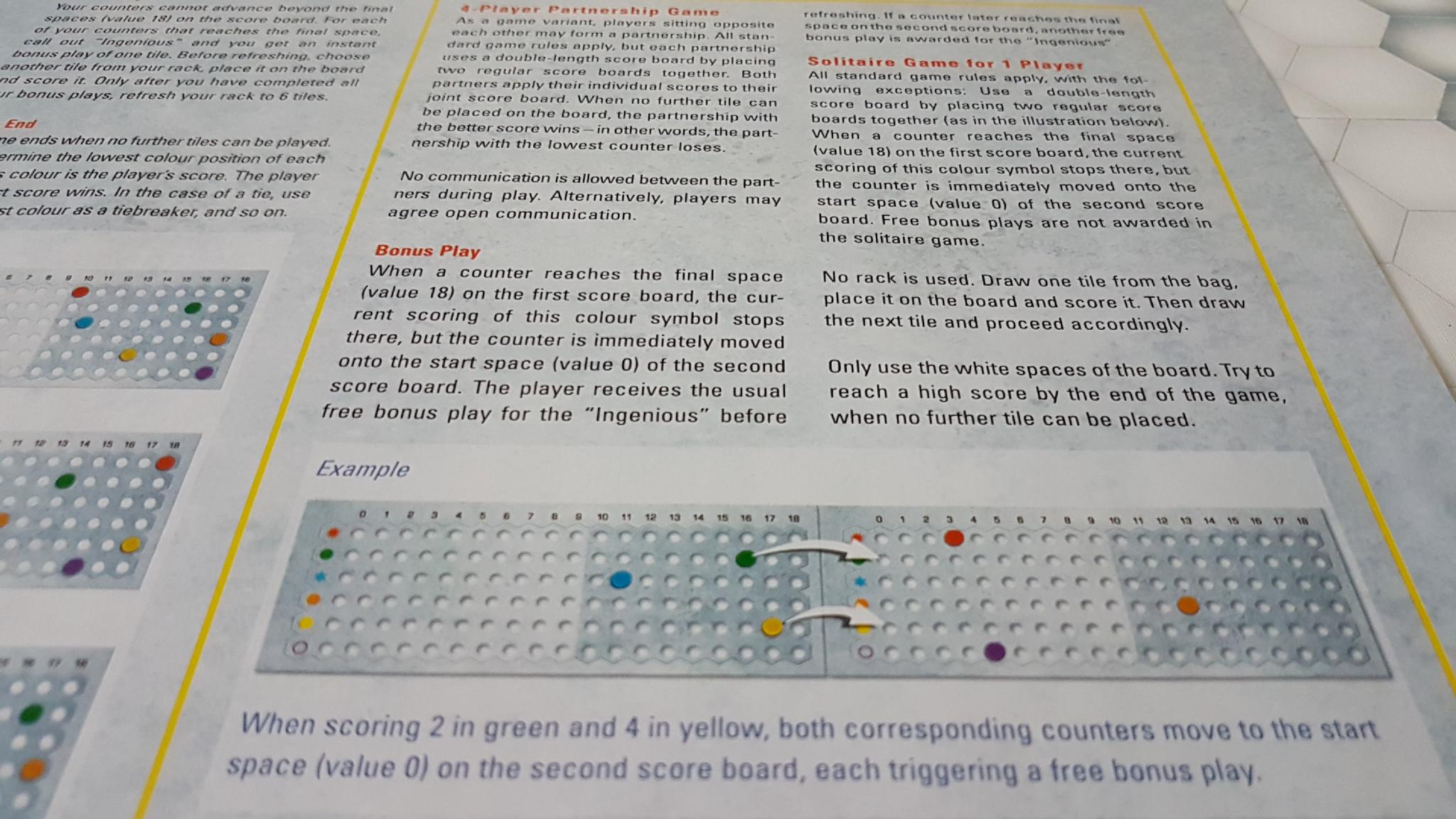

Except the manual. And the manuals – they actually are a universal inaccessibility in board games.

In fact, this is an inaccessibility that goes far beyond disability and impairment – this is an inaccessibility that cuts across the entire hobby. The universal inaccessibility of a board game is its learnability.

Every game has some set of instructions that outline the mechanisms. You might be lucky and find this supported by how-to-play videos or quick starter guides, but the manual is a invariant constant. It’s your first exposure to the game systems and in many cases the only one that you have to unlock how the game works. The manual is the Rosetta Stone of the mechanisms. They’re the shem of the golem creature we find in the box. And unlike most manuals for other consumer products, we cannot divine their contents through experimentation. You can learn how to use your mobile phone by randomly pressing buttons until a mental model evolves. Board games are paper computers, and we need to act like their processors. Any misunderstanding or misinterpretation of the rules will undermine the entire experience. Garbage in, and garbage out. We’re the garbage sorters.

It’s such a huge inaccessibility that I didn’t even think about it when drafting up my first answer to the question. It’s like when you ask people ‘What’s the nearest star to the Earth’ and they entirely forget about the existence of the Sun.

Every board game involves learning rules – not necessarily complicated rules, but rules nonetheless. Some board games involve learning lots of rules. Rules that interact in weird and wonderful ways as the game progresses. Some games require you to learn rules that are designed to be wielded like weapons, where understanding of synergies creates a whipcrack of electricity you can use to stun your foes. Every board game also involves using those rules to manipulate an often recalcitrant game state into a configuration that is advantageous to you. Most of the time, this has to be done while other players are trying to do the same thing in a way that reaps the equivalent benefits for them. You’re often wrestling in a board game, but your holds and throws are the formal rules of the system. The person that understands those moves will dominate the match.

And wow, what a range of accessibility issues a manual presents too. We don’t really talk about manuals much on Meeple Like Us largely because the topic is likely enough for a site in and of itself. Our assumption is that actually learning the game will be done in a way that is handled independent of the manual – with a rules explanation pitched at the group, for example. The circumstances under which people learn a game are ‘out of scope’ for our teardowns.

If they weren’t though we’d certainly have plenty to talk about:

- Font usage

- Backgrounds and contrast

- Presence or otherwise of explanatory diagrams

- Choice of language

- Jargon

- Instructional versus reference

- Structured by system or by order elements are encountered

- Density of text

- Complexity of text

- Headings and subheadings

- Size and bindings

- Regularity of reference

- Duplication of content

- Clarity of explanation

You can see here how all of this cuts across every single category that we discuss on Meeple Like Us and it’s an act of self-preservation to exclude it from our discussions. Almost every group will have compensations they adopt for dealing with the manual. Most of us treat it a bit like some kind of dubious glowing radioactive by-product of play – it’s to be handled only under specialist circumstances by properly trained hobbyists. You need a certain degree of literacy in the structure of a manual to get much out of it. It’s not for beginners.

For most of the games we play, for example, I tell people how to play the game. Since I very rarely actually remember that, everyone gets an excitingly different explanation every time I sit down to teach people something new. I suspect most groups bypass the manual as far as is possible. Most people playing a game have probably done nothing more than leaf through it. Our understanding of the rules is a function of the competence of whoever taught the game. It’s the reason that most people have never read the rules for Monopoly and get really surprised when they find out the version they play isn’t actually correct.

However, that relies on people being willing to teach the rules of a game, and that’s not going to be the case when nobody involved knows how to play. In such circumstances, someone (usually me in my groups) has to knuckle down and read the rules. Then remember the rules. Then try to work out what job each of the rules is supposed to be doing so as to properly explain them in context. I find myself approaching new games the same way I do student essays in a busy marking season. I pick up the next that needs graded, and emit a mournful sigh that has a volume proportionate to the weight of the document in my hands.

I persevere through with game manuals because I don’t have any real choice other than to stop doing the work I love doing. It’s a necessary, unavoidable evil – but it’s also a massive cultural inaccessibility that puts a lot of people off of playing a game in the first place. The manual can be intimidating, and until you learn a certain kind of ludic literacy it’s often opaque, impenetrable and utterly demotivating. Those of us who have read hundreds can comprehend them relatively quickly. Everyone else is going to struggle.

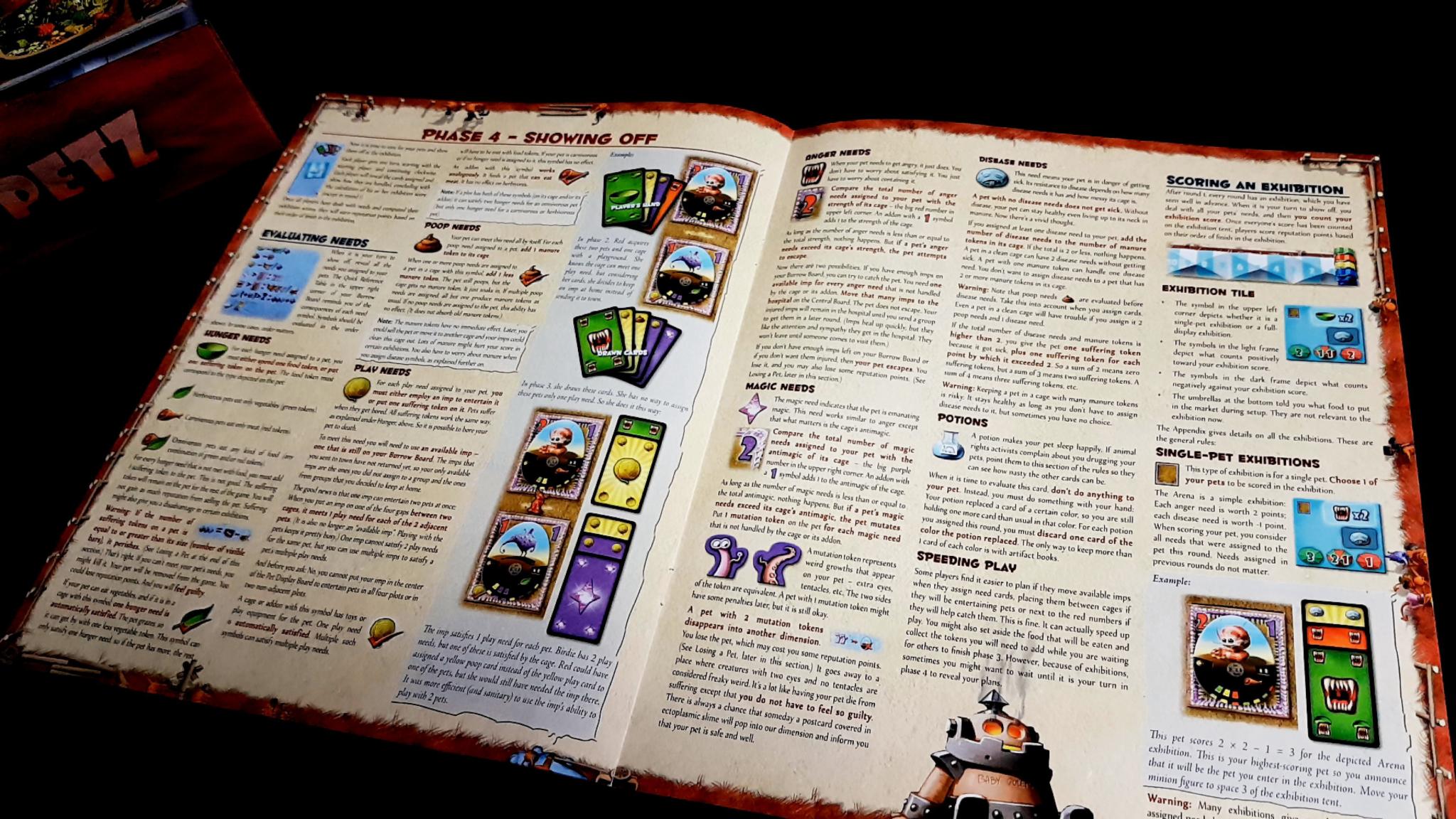

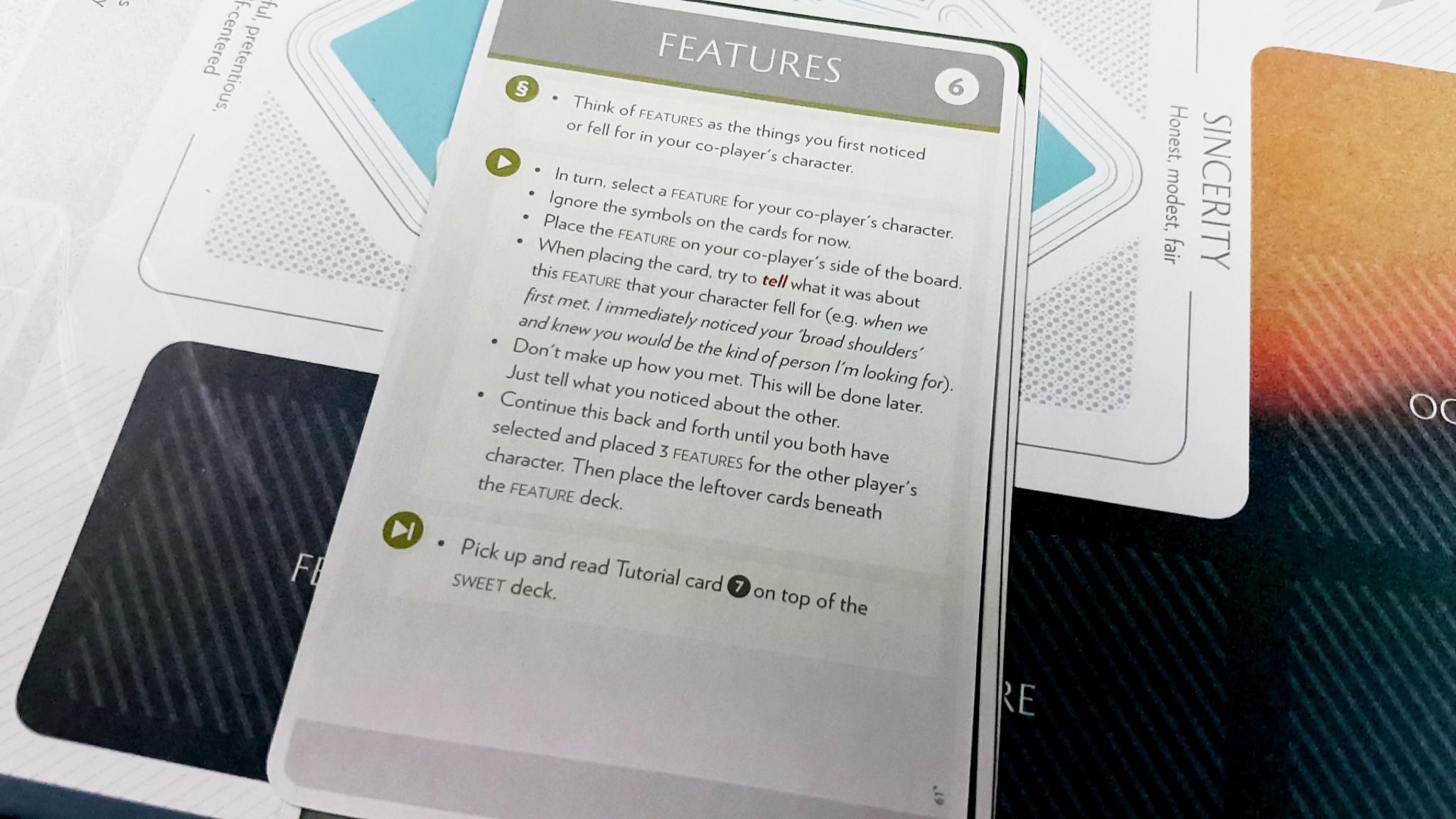

Some people have been innovating in this area by trying to limit the need for manuals in the first place. Fog of Love was widely praised for a tutorial system that involved layering explanatory cards into the decks so that you encountered the rules when they entered scope in the game. It was a nice idea, but unfortunately actually setting up the tutorial was still driven by the manual and it was still just an expository text dump. While I admire the attempt, in the end I would have much preferred to have just had that same tutorial text in the manual presented as an example game. It’s a step in the right direction, but not enough of one.

The Dized companion app promises to offer a more interactive way of learning games, but the library of supported titles is slim and I’m not sure how they’re going to square the cost of development versus the demand for tutorials. I understand their plan is to charge publishers rather than end users, but I don’t really have a lot of hopes that can be sustainable. Perhaps that work could be funded through microtransactions, but I’d never be willing to recommend people pay over and above what a game costs for convenient access to the rules. There are people who do great how-to-play videos – Gaming Rules and Watch it Played being two of the best – but they don’t have rules videos for every game available.

So where does that leave us? Unfortunately, it leaves us in a bad place where the demand for external instructional material far outstrips the supply. We’re not in a position where there are enough people providing good quality how-to-play videos and interactive tutorials that every game can reasonably afford to commission one. We’re still stuck with manuals. I also believe that a universal solution to this universal problem needs to exist in the boxes that we buy. It’s great when people have options but I think it’s bad design to work on the assumption that the solutions to your problems lie outside your control. Instructional videos are great, but they doesn’t alleviate a publisher’s responsibility for essentially ensuring their irrelevance through good source material.

One of the universal solutions is to improve the standards of manuals, but there’s only so far we can go with that – even the best manual is going to struggle to communicate complicated information in an accessible way. Given all the different ways people actually use manuals, to improve in one facet might well be to sacrifice another. To make a manual more effective for reference is almost always to going to reduce its value as a teaching aid. Fantasy Flight and some other companies provide two manuals to help address this problem, but in the end that doubles the workload with nothing close to halving the problem.

One solution is to reduce the average mechanical complexity of games, but I don’t see that being something many people really want. We certainly don’t.

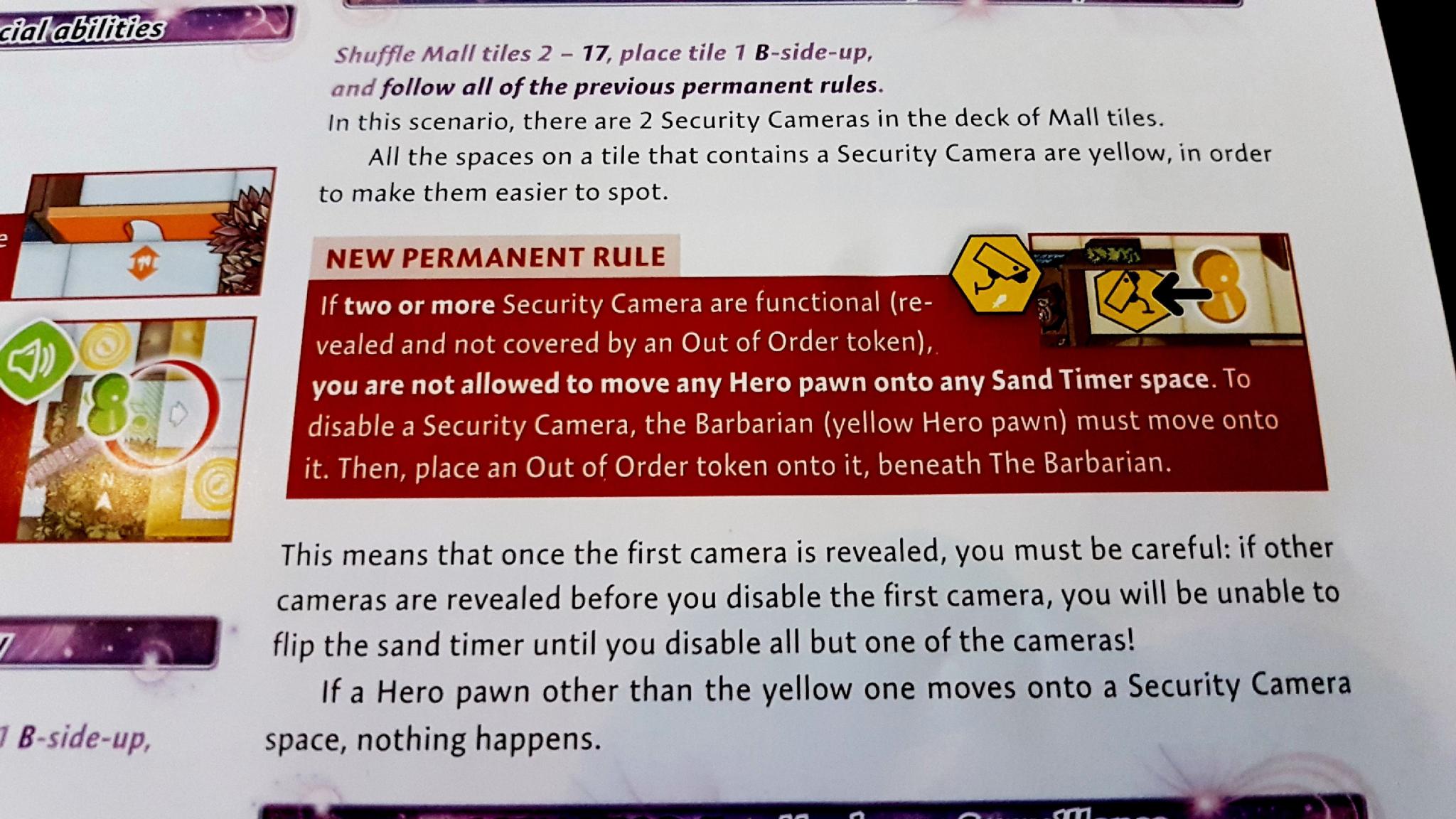

Maybe though our real solution should lie in the lessons imparted by digital games. There are a lot of things video games can learn from board games. What board games need to learn from video games though is how to minimise the gap between opening the box and starting to play. In this, Magic Maze is the game that I think came closest to offering a genuine video game tutorial in a cardboard box. I may not have cared much for Magic Maze, but the scenarios that gradually layered new mechanisms into play were an inspired way to capture the most effective elements of instruction. Its approach was fun, it was succinct, and it was focused. It never introduced anything you didn’t immediately need. It constantly reinforced the core loop of the game, and ensured comprehension through the gradual accumulation of mechanisms. You couldn’t complete a scenario without understanding the new things it introduced and so you never got to the point you were lost with no idea as to when it happened. The Fifth Avenue promo campaign available for Unlock did a similarly good job of teaching (a limited version of) the game through playing.

A good rules explanation should ideally be fun in and of itself. if you think of the video game Portal, it is pretty much one long classroom session that culminates in an amazing final exam. Everything you learn is assessed in the pitched challenge of defeating GladOS. The entire game is one big rules explanation but you never notice because it’s so engaging. The more I look at the games on my shelves, the more I think people should be turning to Magic Maze as an example of how to handle the ‘onboarding’ of the play experience. Treat each game mechanism as a minigame that you need to master before you are expected to make them all work together. Not every game is going to need that, but that ones that do really need it. Ironically, you often see the digital adaptations of boardgames do this better than the original properties upon which they are based. That’s not because the medium is inherently more appropriate but because video gamers have a higher expectation as to what learning a game should feel like. We analogue gamers are letting publishers too easily off the hook.

This doesn’t mean games need to be designed with ‘bolt in’ mechanisms like Magic Maze, although in terms of cognitive accessibility that’s something I absolutely love to see. It just means that each mechanism needs to be fun enough in and of itself to sustain a tutorial exercise that puts it front and centre. Really, isn’t that the ideal design goal of a game in the first place?

I think the ideal game learning environment of the future then is handled like a mini-campaign – where players are presented with a series of systems to master and they progress onto the next stage of the campaign only when they have. That requires a lot more synergy between the instructions and the mechanisms,. It argues that the act of developing a good manual is really a subset of game design rather than editing or copywriting. That’s certainly how it is in video games, after all. These don’t need to exist instead of manuals as we currently experience them, but I’d love to see them existing alongside them more often.

I’d like games to get to the point that when I buy one for a newbie they don’t feel the need to wait for my teaching to be available before they can play. Better manuals certainly help in that regard, but if we’re really going to appeal to a mainstream audience we have to have tutorial experiences that are frictionless and fun. We have that in precious few games now, but there’s no reason we couldn’t have it in many more. I’d much rather a good manual than a bad one, but I’d much rather even a mediocre but interactive tutorial over a good manual.