| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Star Trek: Frontiers (2016) |

| Complexity | Medium Heavy [4.33] |

| BGG Rank | 1074 [7.84] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 1-4 (1-3) |

| Designer(s) | Vlaada Chvátil and Andrew Parks |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

‘Riker, open a hailing frequency to the Romulan warbird. Mr Data, full power to shields. Mr La Forge, I’m going to need you to… wait, hang on. I’ve miscounted. Sorry, belay that. Everyone back to where they started. Sorry, I’ve got this now. Riker, I need you to get on the tactical computers. Data, prep a long range attack package. Geordi… make use of our advanced intelligence to set up a photon torpedo barrage on my mark. One, two… shit, no. No, no, no, the warbird is resistant to photon torpedoes. God, I missed that when I was plotting this out. Everyone back where you started again. Sorry all. Sorry. I’m sorry. Right, let’s try this again. Can someone explain to me one more time about how resistances work?’

I’m on the bridge of the Enterprise staring down a Romulan warship and all I can think is ‘How did Picard always make this look so easy?’

These are the voyages of compression moulded plastic

So, first of all – a disclaimer. I have only played this as a solo game. I have played it a lot though as a solo game – I lost an entire weekend to it, first trying to grok the game systems and then trying to beat the Borg. Mrs Meeple was away for the weekend, and I decided ‘I’ll give this a go’. At the end of my first game, I looked up to see three hours had passed. My first exposure to Star Trek Frontiers told me one thing – I have no desire at all to even attempt to teach anyone how to play this. The time investment, and expectation of mastery, means that if I hold off from my review until I’ve tried it with multiple players it simply won’t get reviewed. I can’t expect anyone to be willing to invest ten hours of play into getting to grips with it. However, boardgamegeek currently has it marked as ‘best at one’, so I think you’re still getting a viewpoint derived from seeing the game in its most advantageous light. If you don’t agree, well – at least you know the basis from which my review derives.

It’s also the case that I have never played Mage Knight, and Star Trek Frontiers is a re-implementation of the core game mechanics of that much lauded title. I choose this one because it was more recent, and also because I am bone-tired of fantasy as a setting for adventure. I’m so, so bone-tired of it. Suffice to say, I won’t be offering you a view of how this one compares to its predecessor. I just don’t know.

What I do know is that Star Trek: Frontiers is a game that comes with a steep appreciation curve. My first game left me thinking ‘Eh, two and a half stars, maybe three if I’m feeling generous’. My most recent play solidified it a good deal higher. It starts off as a game that is simultaneously over and underwhelming – so much complexity for a game experience that is only okay. That’s because you spend so much of that first game poring over rule-books that you often forget to enjoy yourself. You’ll spend a lot of time staring at the rules of Frontiers, and a good portion of that will be thumbing through the two manuals to find out where that key bit of information you need was mentioned.

Bedtime reading and re-reading

The manuals for Frontier don’t have a word-count. They have a word body count. The text is present in a minuscule font dense with half-assertions and rollbacks. ‘You can do this, except in these situations’. ‘You need to do this, except in these circumstances where you don’t’. ‘This is explained in more detail on page fifteen (stress induced rage quits)’. There is just so much to keep track of – the full manual is 24 pages. The companion game walkthrough is another 20. Neither of them is a complete document in and of itself. There’s no meaningful index. No glossary. No lexicon of symbology. It’s all in there somewhere but you better be prepared to go hunting for it.

I’m not even going to try to comprehensively explain how this game plays in this review. Neither of us wants that. I’ll just give you some highlights as we go along and attempt to show off the core experience of play. I can’t get away from explaining bits of it though so just remember – everything is more complicated than I’m making out.

This is what exploration looks like

There are various scenarios in Frontiers, but they all resolve down to the same basic thing – explore the galaxy, level up, fight some bad guys (or good guys that just so happened to be standing in the wrong place at the wrong time), and eventually meet and/or conquer the Borg cubes lurking at the edge of space. You begin with a tiny sliver of the explored galaxy but as you fly your ship around you’ll open up new vistas of space to explore. You start with this:

This is from where our continuing mission begins

And end up with this:

This isn’t a valid map, just one I threw together. There are rules for where you can explore in Frontiers, because of course there are.

The galaxy you construct is dotted with enemy ships, space stations, planets (in distress or otherwise) and other miscellaneous points of interest. Your job as Space Captain is to exploit the galaxy for the resources, training and equipment that will permit you to last in a straight-up fight with the Borg and the confederates they have captured in their neural nets. You’re looking then to progress up this:

Microsoft Space Diplomacy 2016

As you gain experience you’ll gain new captain levels. Skilled captains are more resourceful, can command larger crews of specialists, and are tougher in a straight up fight. Captains also have a measure of reputation that is manipulated by the way they approach the events before them. War crimes inflict a reputation penalty. Peaceful solutions tend to increase your galactic standing. Reputation impacts how easy it is to perform diplomacy and that’s an important currency you’ll need to manage if you want the best people serving on your ship. On the other hand, you’re up against the Borg and you maybe can’t afford the luxury of doing the right thing. Sometimes the prime directive is ‘they send one of your to the hospital, you send one of theirs to the morgue’.

Alpha Centauri Drifting

That said, you’re not necessarily playing the Federation so while this all seems a good deal more morally ambiguous than we’re used to from Starfleet, it’s in keeping with the more robust foreign policy responses of the Klingon Empire. Frontiers has absolutely nailed the theme here – the Star Trek universe works beautifully when transplanted onto the bones of Mage Knight. I’m not so convinced though they’ve been so effective in capturing the spirit of Star Trek. It feels profoundly weird to command the NCC-1701D to decimate an M-Class planet but sometimes the game rewards that kind of scorched earth strategy more than it penalizes. The reputation hit is rarely enough to warrant a moment’s hesitation if you’re playing to win. After all, look at the threat that’s constantly looming in the distance.

Your distinctiveness will be added to our own

The interesting thing here about Frontiers is that it doesn’t even pretend to have the veneer of a story. ‘Borg here, deal with it’ is about as complex as the narrative ever gets. And yet, in the interaction of the various game systems you see story vignettes emerging every single turn. There’s no over-arching tale here, just a series of profoundly thematic story beats that could come straight out of any episode of The Next Generation. The medical officer runs in to heal Riker after his disastrous away mission to the hostile planet. He’s the only one on board with the necessary tactical expertise to pull off the Picard Maneuver that will move the Enterprise out of danger and into attack position. Mechanically, that’s just ‘exhaust the medic to heal Riker, use Riker to generate a red crystal, use the red crystal to power the Picard manoeuvre’. You can though narrate the interaction of these cards with real coherence though with no expended effort. You could script any of these interactions into a random episode of Star Trek and it would look like it absolutely belonged there. That’s a triumph of situated storytelling – of showing, not telling. The theme is more than just the miniatures and the cards, it’s in how beautifully these things mesh together into something more holistic.

Every ship, station and planet you encounter is an opportunity for adventure. At its heart, Frontiers is a deck-builder – albeit one with a glacially incremental development arc. Every player gets a ship deck of cards that can be spent to generate points in particular activities – attack, shields, diplomacy, movement, repairs, and so on. These cards come with three ways they can be employed. Each, aside from the powerful ‘undiscovered’ cards you’ll get later on, has a ‘free’ action. They also each come with a buffed up action that is purchased through the use of data crystals. Each card can also be spent as a low-level ‘wildcard’ to buff up any of the standard actions. Your job as a captain is to look at the galaxy around you, decide what you want to do, and then work out how to make the cards behave in such a way as to let it happen within the constraints of your turn and your hand limit. You’ll begin with a hand limit of five, although with experience and tactical decision making you can increase it as time goes by. Those five cards come with a burden – play them poorly, and you’ll have cause to regret even the simplest actions. It’s a tremendously neat, interesting task that makes every single thing you do worthy of weighty consideration. You can’t even press down on the accelerator in Frontiers without worrying about what it’s going to do to the brakes.

All-in, baby

This turns even the comparatively workaday activity of exploring space into a logistical puzzle. Each sector of space has a cost to go through it and you may only have a few movement cards in your hand. That means balancing the cost of burning data (which comes in short and long-lived forms) against your deck composition against the thrumming heart-beat of the game itself. In solo games, you’re up against a time limit. In multi-player games, you’re usually up against the opportunistic overreach of your opponent captains. Neither of them are going to wait for you to get your act together. You make do with what you have, or you end up having nothing.

Yahtzee!

There’s a set pool of communal dice available for everyone to use – everyone can grab one of those dice during their turn to power an ability. Otherwise, you’re going to rely on those long-term crystals you have accumulated and the short-term tokens you can generate. Data is a precious commodity, and is never available in sufficient quantities. Data represents tactical intelligence, cunning, temporary opportunities, and special circumstances. It represents improvisational flair and combat doctrine. It’s situational, for most sources, and lost if it’s not used. It’s best in many cases not to generate data at all if you can’t use it – unless you can convert it into long term storage all you did was waste it. So – do you burn a blue crystal to go full speed ahead (four movement points), or do you spend a full speed ahead card and an explore card to do the same? That depends – it all depends. Card management in Frontiers is intensely skillful. It’s fair to say if you don’t enjoy this core part of the game, the rest of it will fail to endear itself.

Empathy? In a board-game?

As time goes by you’ll accumulate other cards that represent more powerful tactics, or the unearthly benefits that come from advanced technology or alien artefacts. Everyone begins with the same deck, except for the captain power. You’ll mould that deck though as you advance, turning it into something more powerful. As you engage in combat and take damage, you’ll accumulate damage cards that crud up your hand limit – they stay there, limiting your tactical options, until you can repair the ship. That in itself can be done with certain cards, or perhaps as a result of emergency stop repairs – with these, you shuffle the damage card into your discard deck, putting off the problem until you’re hopefully more equipped to deal with it.

Yeah, the card game in Frontiers is very solid.

This is only about a third of the space this game takes up

There’s more though. That’s the thing about Frontiers – there is always more. Your captain level determines how many special crew members you can recruit, and these will give you more options. Crew members get used up and ‘readied’ throughout the course of the game – they have general utility as ship resources, but also allow you to conduct away missions to planets provided they’re awake and unwounded. You begin recruiting from the ‘basic’ crew deck, but eventually you’ll be able to pick up elite crew members with especially effective powers. You’ll need them too – the Borg don’t mess around and some of the later away missions you undertake are brutally difficult.

This is another third of your game. You’re going to need a bigger table.

The little tokens at the bottom of the play area there represent encounters – these get played face up or face down on the game map to indicate the dangers or opportunities available. Most of them represent specific challenges to overcome through combat or diplomacy. You accomplish these in the same ways as you do anything else – picking cards and making them work for you. The routes to success in these scenarios are many and varied, and the core cause of the almost ceaseless equivocation that forms a turn in play. My favourite section of the game manual is one called ‘reverting’, (p13 of the Game Walkthrough). It explains, somewhat sheepishly, that people should be permitted to perform as many ‘take backs’ as they like provided they haven’t revealed new game information in the process of enacting a turn. That’s handy, because this is what you spend most of your time doing – sometimes because you worked out a more optimal route, but more often because you found a grand plan simply wouldn’t work because of some encounter modifier or special rule you hadn’t taken into account.

Let’s look at a typical example. We’re going to assault a Romulan starbase:

War. War never changes.

See all those little symbols? Those define the encounter. The left hand side is the attack strength, which is three. However, it’s overlaid on an icon that indicates it’s a photon torpedo attack. Unless we have photon shields, all our shield points are half as effective here. The value at the top is the defense of the base – four, except that it has a resistance to standard phasers and also a resistance to photon torpedoes. If we use either, they’re at only half effectiveness. On the right, that icon indicates they’re using antimatter weapons – any damage not absorbed by our shields will be doubled when it gets through to the hull. Oof.

And what do we have? Well, we have this:

Cards against Romulanity

Combat begins with a ‘long range attack’ which lets us potentially blow our foe out of the sky before it gets a chance to hit us. If we can’t exceed its defence with special long range attacks, it’ll inflict damage upon us before we get to inflict damage upon it. Damage isn’t tracked turn to turn for our enemy – we need to take it out in one turn, or start from scratch. We, on the other hand, will accumulate damage freely and happily.

How do we do it? And then, for the advanced version of this same question, how do we do it optimally? Like in any deck builder, efficiency is important here – we don’t want to burn cards we will need later. We need to be careful. We need to be clever.

First option – long range attacks. We need to get a total of four long range attack power to beat the station, and standard phasers and photon torpedoes are only half as effective as usual. Can we do that? We could spend a red energy crystal to power up our engage card, but that would only do one point of damage (since everything rounds down). Chu’lak lets us spend a blue token to generate a four powered long range pulse attack, which would be fully powered. We could take it out with that, but then we’d exhaust Chu’lak and he’d no longer be available for away missions. Maybe there’s another way?

We can’t take it out long-range otherwise, so our first job in an alternate strategy is mitigation – we need to generate enough shielding that we can absorb the three damage of the station. Remember though, it’s a photon torpedo attack. If we don’t have photon shields, they’ll count for half. What do we do? We can generate six shields easily enough – spend ‘battle stations’ and play four other cards as wildcards, bumping our shields up to six. That’s hugely inefficient though, and won’t give us enough flexibility to actually do damage when it’s our turn. That’s not really an option unless we just want to survive this turn and hope for better cards in the next. But what we can do is spend a purple token (from the bank) to empower our improvise card to generate five shields. Or we can spend a blue token to power up our research, play that along with improvise, and discard another card for a total of seven shields. That’s enough to absorb the attack. Then, if we power up battle stations with a yellow crystal, power up engage with a red crystal, and play our intimidate as a wildcard we’ll do eight points of phaser damage and take the base out. That’s a lot of cards and data, but cards at least replacements from our draw deck will cycle back into the hand when we’re done. Exhausted crew have a longer-term impact on our effectiveness, especially given some captain bonuses that might make their way into our possession.

Which should we do? It depends!

Mr O’Brien, energise

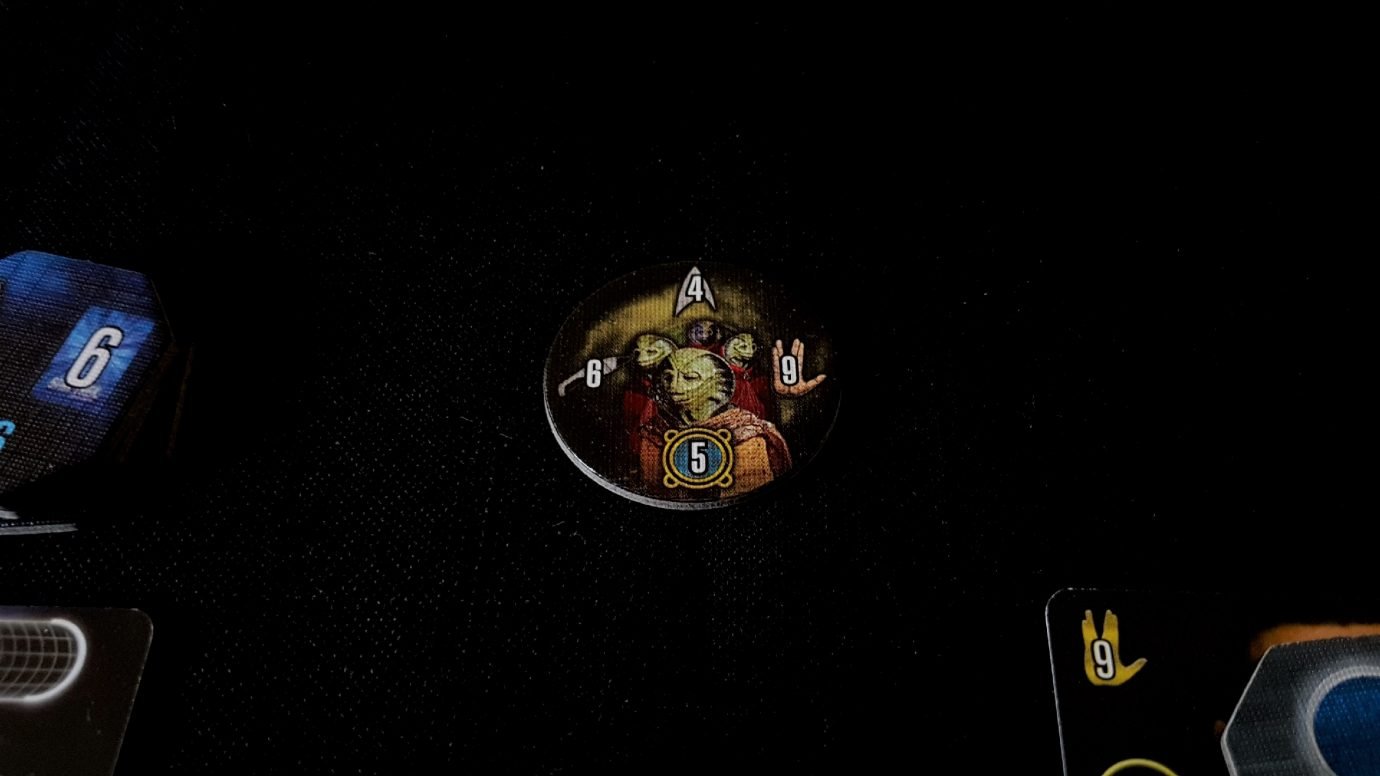

Here’s another example – an away mission is resolved first with diplomacy (the value on the right, which is nine). Only crew members actually assigned to the mission can use their special skills there, although we can play ship cards as usual. If diplomacy fails, we move to long range attacks. If that fails, all of our away team take damage equal to the phaser value (six, which needs to be spread around away team members – shields don’t work here) before we get a chance to fire back. How do we do that?

Away-missions require a fair amount of paperwork

Let’s say we’re sending Riker and a medical officer. Well, we might spend a red token to power up Picard for a diplomacy of four, then exhaust Riker to give us another four, then intimidate to give us ten, which exceeds our target. Or, before we go on the mission we might exhaust Riker to generate a red crystal, revive him with the medical officer, send Riker alone on the mission and spend two red crystals on Picard and Intimidate to give us nine. That way we keep Riker ready for the next mission at the cost of our exhausted medical officer.

Which should we do? It depends!

You spend a lot of time in Frontiers immersed in optimisation challenges like this, trying to stare into the heart of your cards to see the best way to play them to accomplish what you need them to do. That challenge becomes even deeper when you encounter situations where you need to face two foes at the same time, or orbiting ships followed by an away mission, or collaborative raids on the Borg. Every single activity is going to need furious consideration and careful planning, using every last ability available to the absolute utmost to eke out every fractional efficiency improvement. It’s less like flying a spaceship and more like being engaged in a frantic exercise of extra-solar Excel. Your deck is a tool you’re constantly shaping to help meet the escalating challenges you’ll face. When you finally encounter the Borg you’ll be in a pitched battle against deadly cubes and their escort of warships and enslaved shock-troopers. You’ll end the battles riddled with damage, limping away to repair just so you can go in and mop up the rest of the defenders with a vague expectation of survival. You beam down to away missions on distressed planets and come back with only phaser-fire scarring and a cautionary tale. This is not a game that’s going to coddle you. It’s perfectly fair, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

A universe of possibilities

It’s important to note here that I’m only touching on the rules in the simplest way – there are pages and pages and pages of legalese about how everything works. There are rules for how to partition and allocate damage and shielding; when cards can be played and how; and the impact of captains on away missions – everything is embedded in a concrete shell of complication. Frontiers is a game that plays well, once you get the hang of it. It’s very much a game that doesn’t play smoothly. You will be constantly consulting the rules, and you’ll still mess things up. There’s just so much to learn. Just so much to remember. It’s not like it doesn’t come with a quick reference, but that quick reference refers only to different encounter types and comes in enough cards of its own to make a decent sized playing deck:

Yep. The quick reference cards. Brew up some coffee, you’re going to need it.

Is it fun though?

God, I don’t know. I don’t know. I honestly don’t know.

It’s certainly absorbing – in all the games I played, the only time I looked up from what was going on was when it was over. The two-ish hours of playtime get swallowed up whole as you commit yourself to the beautiful complexity of the experience. The whole thing is a bit like entering a trance state – it’s not a state of flow, but a state of total involvement in an ongoing problem of stellar logistics. I can’t tell you though whether I had fun playing or whether I was just entranced by the intoxicating puzzle every task becomes. The best I can say really is that it’s time I don’t remotely regret investing.

It is though also time that I wouldn’t dream of asking anyone else to invest. Star Trek Frontiers grew on me the more I played it, but I don’t think I could ever really be an effective advocate for anyone else to pick it up. I’d happily play it with anyone, provided they already knew how the game worked. I wouldn’t want to be the one to teach this to anyone, and even if they knew the mechanics I wouldn’t want to be around while they developed literacy in the game systems. I enjoyed the solo experience, and that’s important – it’s pretty much the only way I can ever envisage being able to play it again.