Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Star Trek: Frontiers (2016) |

| Complexity | Medium Heavy [4.32] |

| BGG Rank | 1053 [7.85] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 1-4 (1-3) |

| Designer(s) | Vlaada Chvátil and Andrew Parks |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

Star Trek: Frontiers is a game with a lot of depth to it – so much depth you can sink in and never see daylight again. We gave it four stars in our review, but that doesn’t necessarily parlay itself into a recommendation. Fittingly for a game that makes you spend most of your time equivocating over the right course of action we’re still not entirely sure it counts as actual fun. That cowardly fence-sitting though is not what you’re here for – you’re here to us to boldly go where no reviewer has gone before. Set phasers to teardown.

Colour Blindness

Colour blindness is a consistent problem through play. Each of the Borg cubes has a colour that identifies its specific behaviour, and the colour exhibits a palette clash for everyone:

We have been assimilated

Colours on the dice often bleed into each other. This isn’t a problem as such because they also come with their own distinct symbols, but this is a game that tends to sprawl and sprawl. Colour identification is a huge benefit for ease of play when you might be staring across to the other side of a big table to work out what’s available.

Icons salvage this problem

This is more of a problem with the data crystals that players will accumulate – colour differentiation isn’t good, especially when considering the blue and purple tokens.

Why so many kinds of Data? What makes him such an important character?

Faction indicators come with symbols on them, and while they are usually identifiable by colour for all categories they’re not as distinct as we’d like.

Be prepared to get up close

Cards are colour coded to show the dominant data type of which they make use. The cards are fully explained without requiring this to be perceived but there is a real benefit to being able to see at a glance how much oomph you’ve got in the various categories.

Hoist by their own Picard

None of these are truly game-breaking problems – each of them has a compensation. The key thing with Frontiers though is just how complicated it is – everything you do to fix a problem here is going to add just one more thing of which you need to keep track. Getting up close to the various clashing colours and dice to see the symbols is going to detract from flow, and really there’s enough going on without adding calisthenics to the mix.

We don’t recommend Star Trek: Frontiers in this category. You can compensate for the issues here, but this is a game from 2016 and you really shouldn’t have to.

Visual Accessibility

The visual accessibility of this game is uniformly poor, made worse by a garish and ugly colour palette. Really, there’s almost nothing positive I can say here – so let’s get stuck in to the negatives.

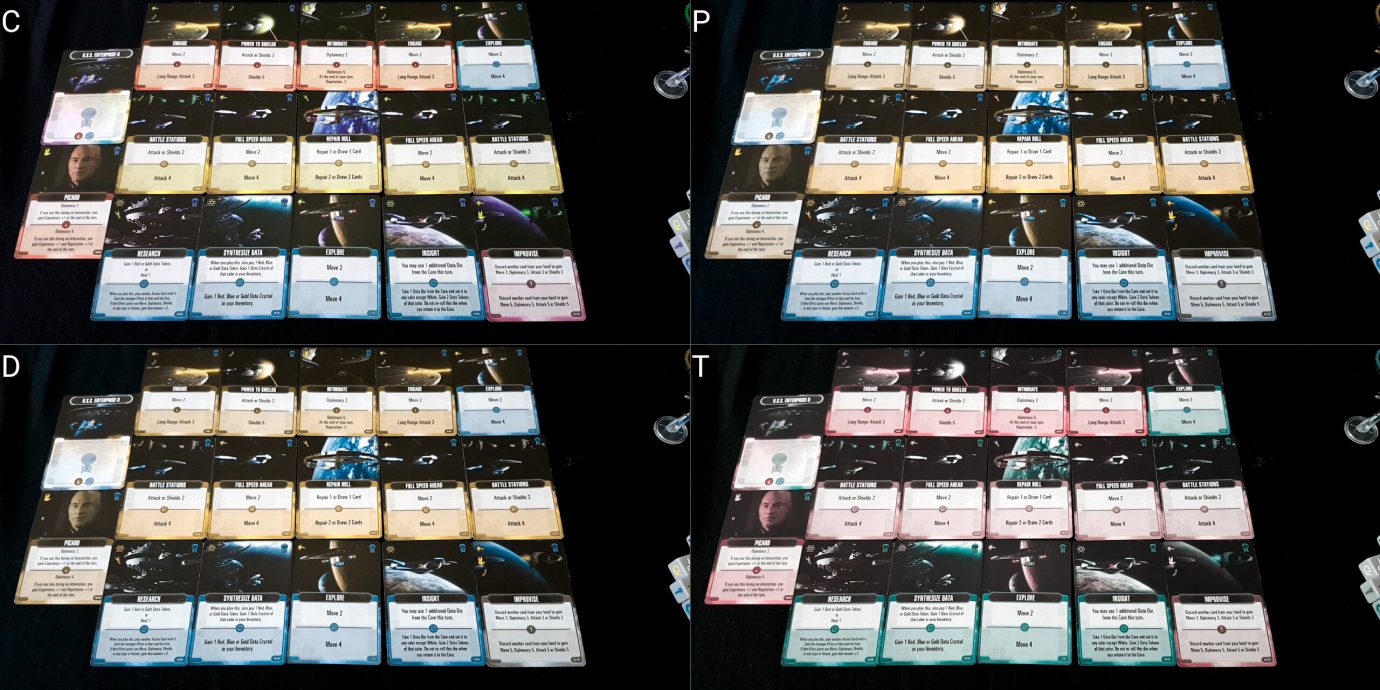

First of all, this is a game that massively sprawls across a table.

This is just for ONE player

You don’t often need to know what your opponents can do – it’s a very solitaire experience except when engaged in PvP or collaborative raids on the Borg. As such, you don’t need to often be able to peer into another player’s area and pick out their crew and cards. However, you will need to know an awful lot other than that. Here’s a partial list of what’s constantly relevant:

- What systems have been defeated, and by whom

- What enemies are on the map

- The strength and capabilities of revealed ships and bases

- Unrevealed bases that need scanned

- Planets, and their type

- And whether there’s a left-over away mission there

- Ownership of conquered Dominion and Romulan bases

- Contents of hexes, for movement purposes

- What’s available in the crew offer

- And what that means for your ship

- What’s available in the undiscovered offer

- And what that means for your ship

- What’s available in the advanced techniques offer

- And what that means for your ship

- What dice are in the data core

- What reputation you have

- What experience you have

- What tokens are available in the skill offer

- Your own drawn hand

- Your ship inventory

- The disposition of your ship crew

- The skills available to you

Playing a solo game will take up the majority of a reasonably large dining table. Everything that is laid out is important to know. The cards themselves are reasonably accessible for the most part, at least as far as skill effects go – curt and clear language is used in a reasonably large font. Everything else is a problem, including the amount of conditionality expressed on each.

‘I think Riker is available in a giant space crab?’

Crew cards are especially bad. They show the availability of crew members for recruitment (the little cartouche on the left hand side) – even fully sighted this can be difficult to make out and is inconsistently contrasted on different cards. Diplomacy to recruit is overlaid onto an icon that makes it difficult to read. Similarly with defence values and level – ornamentation makes it a trickier task than it should be to pick out.

And then there are the tokens which are just comically bad. Look at them:

Token reprentation

In a tiny circle we have combat values, special attacks, special resistances, additional weaponry and numbers overlaid onto encounters. All of this needs to be considered against the encounter token abilities to understand how it all works:

Yeah

Can you even see the biogenic weapon icon on the Romulan warbird (centre left)? Can you easily make out that disruptors are used by the Romulans on the centre right? It looks very much like an extension of the artwork. It’s all made harder to read too because of the ugly, clashing colours. They’re not much better either when you see them from the other side. It’s really easy to get mixed up, drawing the wrong tokens or picking up a Borg sphere when you meant a Class-K planet. Some planets have a vague red halo around them to indicate that they’re currently in distress, and that changes the tenor of the encounter. And then, remember, tokens like this are strewn all around the game map in face-up and face-down configurations.

And then let’s talk about the manual(s). Usually we don’t discuss manual issues here because we work on the assumption that someone will be there to explain how the game works, and that in those cases where it’s not possible someone will download a PDF of the manual and read it in an accessible format. It only becomes an issue when the documentation becomes a part of play, such as with Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective or Tales of the Arabian Nights. Here, it’s an issue because you will absolutely need to keep checking stuff in the manual because there is so much complexity to how everything works. And when you check the manual, you’ll see it is in a ridiculously tiny font that is layered in dense paragraphs throughout dozens of pages. It’s a train-wreck from an accessibility perspective, and not much better for fully sighted players.

Look at this goddamn thing

At least there’s a quick reference though, right? Yeah, about that. There are cards that define how encounters work, but you need to either have them take up a huge amount of table-space or flip through them to find out what you need. The text on these is also tiny.

‘At a glance’ info, providing the info you want is ‘there’s too much info here’

Or you can refer to the quick reference at the back which doesn’t have nearly enough information to permit the game to be played, and is presented in the same unreadably tiny font.

A summary longer than most novels

Some of these problems are consequences of the design. The font choices and aesthetics though are fixable problems and it’s really disappointing to see them so egregiously represented here. I understand a larger font size would result in thicker manuals, but there’s a point at which miniaturisation becomes nonsense and that point was several font-sizes larger than what Frontiers offers.

It’s unfortunately a complete fail in this category.

Cognitive Accessibility

I also have nothing good to say here. In this section though at least the problems are related to gameplay rather than poor aesthetic choices.

First of all, the game layers on an escalating challenge – early encounters with Romulan warbirds are reasonably easy for a starting ship but there is a risk evaluation that must be carried out before engaging. You might encounter a 4/4 warbird that is a straightforward challenge, or you might encounter a 3/4 warbird tooled up with disruptors or antimatter weapons. These are radically different fights in terms of the challenge they offer. Ship combats and away missions become incrementally more difficult as time goes by and the low-hanging fruit is picked off. The sheer number and interaction of tokens too adds its own cognitive complexity – different parts of the game behave differently when they have been claimed by a faction than when they haven’t, as an example.

Meeting that challenge requires a player to be able to effectively manipulate their deck. This requires explicit numeracy and a considerable degree of literacy to back it up. The numeracy here isn’t even necessarily just arithmetic – it’s conditional and often has to deal with fractions and rounding along with multiplication. More, all of these are often performed on only part of the calculation – if you are attacking a photon torpedo resistant enemy with four points of torpedoes and four of phasers you only halve the torpedo damage. Sometimes you’ll be partitioning these elements across multiple enemies too, or resolving them in two separate attacks.

Card play is highly dependent on an ability to recognise and manage card synergy – this is really the core skill the game requires. You need to be able to see how cards chain together and what you can do and in what order to accomplish the maximum benefit. The order in which you play cards is as important as the cards you actually play. The game does formally allow a ‘take back’ for actions, but that doesn’t address the fundamental difficulty associated with playing cards well.

Consistency of the rules too is erratic – for some activities you move into hexes, for others you deal with them from an adjacent hex. Some encounters must be resolved instantly, others are resolved in multiple steps. The way you conduct an away mission is different to how you conduct a ship combat, and both are different to how you handle a class-H planet encounter. PvP combat has two different ways in which it can be conducted. Some encounters chain together two or more other encounters, often of different categories. Some encounters can be resolved collaboratively. All of this is highly specific to context, and executing upon these assumes that the basic rules themselves are comprehensible.

Even if none of the things we discussed above were an issue, the game still presents cognitive accessibility barriers due to its sheer complexity and the number of rules and different situations. The full manual includes rule sections for dozens of things, including but not limited to:

- How to use skills

- How to use crew members

- What cards can be played when and how

- The accumulation and storage of data

- Emergency repairs

- Movement and limitations

- Moving around and through destroyed Borg cubes

- Attacks of opportunity

- Exploration of new spaces

- Scanning bases and cubes

- Spending diplomacy (which works differently on away missions and in ‘interactions’)

- Interactions available at Borg cubes

- Where to get healing and repair

- Recruitment of crew members

- Multiple purchases in a turn

That’s a partial extract from four pages of the twenty-four page full rulebook. If nothing else, the number of different rules and their highly situational complexity and subtlety would render the game inaccessible.

We cannot at all recommend Star Trek: Frontiers for either category of cognitive impairment.

Emotional Accessibility

The largest issue of emotional accessibility here is in the stress that comes with trying to learn the game in the first place. It’s a frustrating experience to look at this vast, complicated thing and feel yourself failing to grasp it. Coupled to this is the fact that there’s no point at which it just clicks – it’s a gradual accumulation of familiarity that eventually tips over into a sense that you’ve got a grip on what’s going on. Constantly though you’ll be reminded of things you’ve forgotten or failed to take into account, and that usually needs you to fully reconsider the plans you may have laid. When revealing new game information you don’t get to retract either, meaning that you might well find yourself facing a foe that you can’t hope to defeat. The cost of loss is relatively minor, but it can take a lot of time to fully undo the results of a mistake. That’s galling when the mistake was due to some weird intersection of rules that you didn’t quite instantly parse.

The game permits direct PvP, but it doesn’t have particularly dire consequences – it’s not Merchants and Marauders. Instead, a defeated captain is forced to retreat and suck up the damage inflicted. There’s no player elimination, but also nothing that would disincentivise a group targeting a runaway leader to prohibit their progress. It’s not the meanest PvP we’ve ever seen though, not by a long-shot.

The challenge in the game is perfectly fair – while there is a degree of uncertainty as to what you’ll face in a combat or away mission, you’re never at the mercy of the dice. It’s entirely deterministic once the encounter begins. The game does become more challenging as time goes by – more interesting enemies are revealed (particularly the Borg) and the easier challenges are snapped up. It never feels arbitrary though, and the Borg encounters come with the ability to scale to the desired challenge. The reference cards for the cubes show exactly what that challenge would include:

Scalable challenge is a great feature

Overall then, we recommend Star Trek: Frontiers in this category. Phew, a recommendation.

Physical Accessibility

Here, the problem becomes one of sprawl. There is so much space taken up by the game that physically getting up is almost mandatory – you’ll need to inspect crew offers, techniques, and undiscovered cards as well as the state of the board. For everything listed in the visual accessibility section, it’s true here too – you’ll need to be able to examine these things up close. There’s nothing to stop someone handing things over for closer inspection, but that’s far from ideal.

Much of what you have to define your ship will be directly in front of you, but it’s also necessary to hold your hand of active cards. A card holder here will help, but while the hand limit begins at five it’s modified by captain level and tactical choices at the beginning of the round. Hands of eight or more cards are not uncommon in later stages of the game, and the act of playing them is one that needs to be handled physically when you’re stacking them together for impact. If playing without direct PvP engagement there’s little danger that comes from playing a hand open on the table in front of you, but it would have some game impact in highly competitive groups. Knowing that you have the movement to get to an outpost, and the diplomacy to hire a particular person, could influence someone to get there before you just in case.

You’ll be using lot of these

There are lots of little tokens too in play, including the stack of skill tokens from which you’ll be drawing when you level up, and the captain level tokens which need stacked and kept in a certain order.

Command tokens are placed on and off of crew members as they are used, and skill tokens are flipped (sometimes) when they’re employed. Your ship card will have accumulated data crystals, and you’ll also have a stack of faction tokens you should be distributing around planets and bases as you conquer them.

The map itself too has a tendency to become dislodged – the pieces nestle together, rather than snap together. The result is that a careless movement can cause faction tokens, ship models, and distributed enemies to shift. You can always relocate them back where they came from but it can be a problem on occasion because of just how busy the board is with tokens and ships and other identifiers.

And of course, Frontiers is a deck-builder and you’ll need to shuffle your deck when you reach the end of it. That’s a once per round activity though, but thoroughly shuffling is going to be important because cards tend to get discarded in stacks of related action points and otherwise you’ll deal them out with very identifiable, and abuseable, clumps.

Verbalisation is possible but not particularly easy. Maneuvering through space requires specific positioning and has no particularly easy way to refer to navigable elements since they don’t differentiate themselves. A few planet names or noted features wouldn’t have gone amiss here.

‘Move me to the Class H planet beside the Class L planet’

‘Uh – which one?’

That’s not the problem though – the problem is in just how much you need to be constantly revising and changing your plans. You can certainly talk through your options in a way that permits someone to actually make the actions for you, but often you’re just thinking aloud. The nature of managing the state of your plan means temporarily distributing dice and data tokens around the cards to signify intent, and you’ll often find half-way through that you need to undo some or all of your plans and reset everything back to its original state. Verbalisation then requires an unusual degree of patience on the part of both players.

We don’t recommend Star Trek: Frontiers in this category. It’s playable if you want to really make the effort, but at a considerable cost to game flow. Bear in mind that cost to game flow is in a game that is already difficult to play.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

With an RRP of around £75, this isn’t a cheap game – weirdly though it feels like one. The component quality isn’t poor, as such, but feels somehow ‘budget’. The miniatures don’t look good, the cards don’t feel nice, and even the box feels like it should be holding a budget set of Christmas crackers. There is though plenty of replayability in there. BGG suggests it plays well from 1-3 players, and I’ve seen a fair amount of commentary that suggests at four it grinds on a bit. You’re paying a lot for a game that tops-out at three players for most groups.

Star Trek has a reasonably strong legacy, as a franchise, of inclusion and diversity. The first interracial kiss on television was Kirk and Uhura. The first season of TNG had men in skirts as a nod towards the egalitarian gender equality of the 24th century. Voyager was captained by a woman, and the whole franchise is full of great and interesting characters of varied ethnicities. Sure, it’s not always perfect and on occasion it veered into borderline grotesquery. It always had good intentions though, and an awareness of the issue of representation that was completely absent in many contemporary series. Unlike in the Orig Trig of Star Wars, there’s a lot of canonical meat there to draw from when it comes to crew selection. Unfortunately though Frontiers hasn’t made the best possible use of it. These are the standard crew members available for recruitment:

Troi was always my favourite.

Note the presence of Worf, La Forge, Riker and Data. Note the absence of Beverley Crusher or Deanna Troi. One of the ‘Federation Officers’ is a black woman, and one of the medical officers is a woman too. Toreth and Donarta are women as well so it’s not bad as such. It’s striking though to see four men from the NCC1701D and none of the women.

The bad-asses

In the elite crew we get Sela (the Romulan version of Tasha Yar) and Seven of Nine – strong women characters, but not many of them. Where’s Dax, Torres, or Nerys? And then for the captains:

Here comes the new boss, same as the old boss

You can be Lursa and B’Etor there, but it seems poor form to have the only women captain(s) be the ones that are described in the manual as ‘self-serving and full of treachery’. What if you want to play a noble, heroic female captain? You can certainly play them that way, but you’re playing against type.

There’s such a wasted opportunity here too, because the only difference between the captains is their one special card – they’re otherwise shuffled into a deck that is identical to that every other captain. Why not let Janeway, or Dax, take control of a federation ship? They don’t need to have different ships – just let people choose a ship and a captain. I don’t know, there might be canonical reasons for this but Sisko has a captaincy here and Seven of Nine is a recruitable crew member so clearly DS:9 and Voyager are considered ‘within scope’.

I appreciate that there’s a need to balance provision of these characters between Klingon, Federation and Romulan but I think they could have done much better here than they did without even venturing outside the safe, shallow waters of TNG contemporary television Star Trek.

Nonetheless we’ll tentatively recommend Star Trek: Frontiers here.

Communication

There’s no formal need for communication, but the literacy level required spikes up into the stratosphere. Usually literacy issues would be enough for us to say ‘Bear this in mind, but we recommend it anyway’ but here it’s different –the ruleset for Frontiers is not learnable in the same way as most games. Constant reference to the manual is going to be required, at least in the short to medium term.

If language issues are the key communication problem, we’d advise you to stay well away. Overall though we’ll offer a tentative recommendation.

Intersectional Accessibility

There are no intersectional issues here that would turn a current recommendation into the opposite, or vice-versa. As usual, communication impairments paired with physical impairments would render the game inaccessible but we don’t recommend the game in the physical category. Visual and physical accessibility concerns would make dealing with the game state more difficult still, but we advise against the game for both categories anyway.

The game length is – long. Each of the solo games I played took around two hours each. The box says ‘one to four hours’ but I don’t know what they’re smoking to have come up with the lower-end of that. Assume ‘two hours and up’, with that figure increasing the more people playing and the more accessibility compensations that need employed. It’s easily long enough to exacerbate issues of emotional and physical discomfort, especially give the intensity and complexity of the experience. There’s a lot of down-time too, which means that players with emotional control or attention issues will find it a frustrating experience. Were I to play it as something other than a solo game I would be reluctant to play it with more than two players.

There’s scope in the game for allowing players to drop out – players might have crew and tactics and the like in their deck that need redistributed into the supply, but otherwise they can just be removed from the usual rotation of turns. Solo play is dependent on a dummy player to act as a timer, but with a little careful thought it’s even possible to scale down from two players into a solo game without too much negative impact. That’s a blessing, given the length of the playtime. If people want to bow out, they needn’t feel obligated to continue.

Conclusion

Well, we’ve got a new champion for the title ‘least accessible game we’ve looked at’. Blood Bowl was the previous holder of that dubious honour but Star Trek: Frontiers manages to comfortably limbo under the bar previously set. Some of this is just because Frontiers is an intensely complicated and complex game. Lots of it though is down to baffling design decisions.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | D |

| Visual Accessibility | F |

| Fluid Intelligence | F |

| Memory | F |

| Physical Accessibility | D |

| Emotional Accessibility | B |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | C- |

| Communication | C |

The bad news is that we can’t recommend this game to almost anyone. The good news is that there are plenty of opportunities for easy accessibility wins should Wizkids want to deliver an accessible second edition of the game. A less garish colour scheme would improve visual accessibility, as would better colour choices or signifiers. Move away from the tiny encounter tokens to something more substantial, with better contrast and clearer indication of special powers and defences. Soak up the marginal additional printing costs and go with an actual readable font. A reference card for encounters rather than a series of awkward cards. More actively streamlined rules, and greater rules consistency. And so on. And so on.

As things stand though, this is a game we would advise most players with impairments avoid like the plague. That’s a shame, because we rated it four stars and that shows we think there’s real merit to the experience. However, it’s also a game that we would struggle to recommend even with that judgement because it doesn’t start out as a four star game. It starts off at two-ish stars and gradually grows more as time goes by. While its fundamental inaccessibility means that you’ll be missing out on a potentially worthwhile experience, you could play and enjoy ten more instantly enjoyable games in the time it’d take you to think ‘right, now I’ve played three test games I think I can actually start actually playing Star Trek: Frontiers’. That makes it a difficult sell at the best of times. For those with accessibility needs, I wouldn’t even make the effort.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.