| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Onitama (2014) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.64] |

| BGG Rank | 317 [7.35] |

| Player Count | 2 |

| Designer(s) | Shimpei Sato |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Remember how I didn’t like Hive? I’m sure you do – you’ve got all these reviews committed to memory. You love our reviews so much that you’re eagerly waiting on the spoken word audiobook so I can be your bedtime companion. You want to lie there, in the dark of some cool, fragrant night with me whispering gently in your ear. I’m sorry to have to disappoint you there. I’ve been told by medical experts that the combination of boardgame analysis and my soothing Scottish brogue would be a combination too powerfully erotic for people to bear. For safety reasons, early recordings of ‘Meeple After Dark’ have been crated up and stored in a governmental facility deep in the dark Earth. They’ve got Top Men studying them.

Wow – well, that went off topic pretty rapidly. Let’s try that again.

So, remember how I told you to remember how I didn’t like Hive? Let’s talk about Onitama.

Hiiii-ya!

Onitama is the game that Hive wanted to be – something abstract and chess-shaped that meaningfully obsoleted the original. Gone are the fixed open strategies of chess. The static and even fossilized strategic wisdom is thrown out the window. The austere contemplation of a rabbit hole of formalised moves is dead. Hive accomplished all of that but retained many of the problems of chess. It was still a largely dry, joylessly sterile experience of incremental positioning. It still required the development of skill and mastery, and rewarded that mastery with an insurmountable advantage in mismatched play. Hive certainly has its passionate advocates, but I’d never even think about recommending it as an idle way to spend a lazy afternoon. It has fallen too flat, too often, to be worth the risk.

It’s marvellous then to see Onitama, which manages everything Hive did and is also fun and exciting to play. More than that, it manages all of this in a set of rules that are so effortlessly simple to comprehend that there is almost nothing to learn at all. It’s remarkable. Even its box is a testament to its elegant design, standing proud like a tower and unfolding like a flower. You don’t so much open Onitama – you unwrap it.

You’re the best… around…

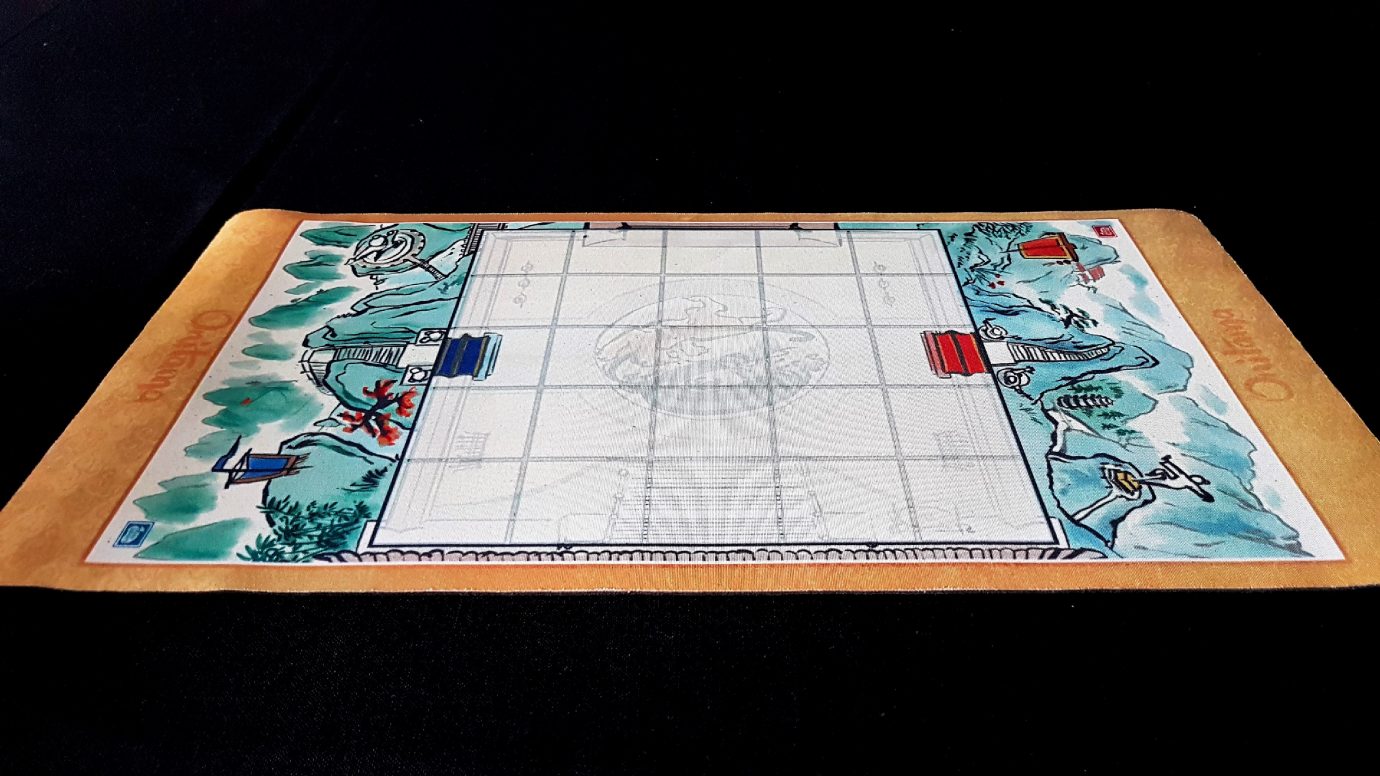

The simplicity of the design is amplified by the sparse components. You get a rolled up mat that becomes the board in a very Cube Quest fashion. It’s like taking a scroll of ancient martial mysteries and unrolling it on your table.

You’re gonna fight like Picasso – because you’ll spend a lot of time on the canvas.

You get five pieces per side – four students, and a master. These get set up facing each other across the board. Here you might start to call foul, pointing out that this is the very definition of a chess-like fixed setup and I just said that Onitama solves that problem. You’re certainly right too, on the surface. But just wait – this get interesting.

Hi-ya!

The last thing you’ll get in the box is a set of sixteen cards, and these is where you find the genius in the design. Five cards are randomly dealt out – two to each player, and another off to the side. The two cards you have in front of you are the moves you can make with any of your pieces. When you’ve used that move, you swap it for the left-over card. OoooOoo. All the cards that weren’t dealt out go back into the box to await another game. Every single game of Onitama has its own unique form of martial artistry that you need to master.

Karate for defense only

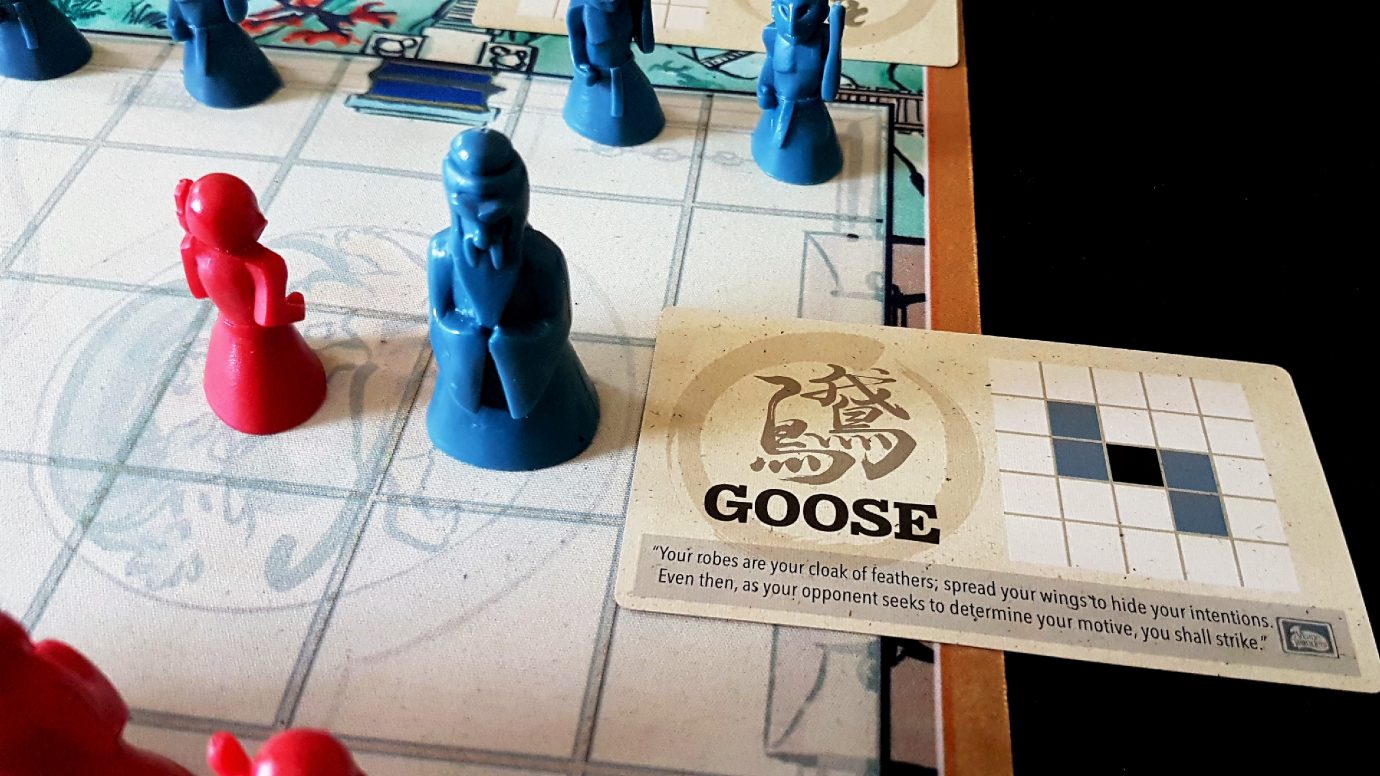

Consider the image above. Red here has access to the Goose and the Mantis – any red piece can execute either of these, and they enable varying degrees of mobility. Shaded squares on the grid show what movement is permitted from the chosen piece’s location. Mantis allow a piece to move forward and left or forward and right, like a pawn capturing a piece. It also permits a piece to move backwards with all the serene brutality of the back of a head being driven into an unsuspecting nose. Goose permits a forward left, left, right, and backwards right movement. You can’t make any other moves – you pick a piece, you pick a move, and you execute on it. If you’ve got any sense, you’ll also yell things like ‘GOOSE STRIKE’ or ‘MANTIS ROLL’ as you do. C’mon, get into the spirit of it.

This is a game of chess that plays like a ballet.

Cobra Kai ready to go

This ludic architecture creates a truly beautifully balanced asymmetry. The last time I was so enamored by a mechanic was Kaylee in Firefly. Both players have a different set of moves available, but in the act of making a move you cycle it inevitably into the hand of your opponent. You don’t have to worry about your opponent having access to better, more effective cards – you just need to worry about how to make use of your momentum so as best to curtail that of your opponent. This is a game about absorbing and retaining movement so as to play it back – it’s a game of shaped motion. It looks like chess, but it plays like an immaculately choreographed martial arts movie. Bruce Lee was a dancer before he was a Hollywood superstar and originator of Jeet Kune Do. Onitama captures just how natural that progression must have seemed to him and everyone around him.

This is a karate dojo, not a knitting class.

The card that is dealt out of the flow of play has a colour that indicates which player is to go first – red plays the Goose, sweeping a student into the fray. Any piece can trigger the move, which means you’re not looking to handle intricate positions – you’re looking to have pieces in those locations where you feel you can best capture the rhythm of the contest. The battle, or dance, continues until a master is captured by another piece or until the master stands in the temple square of the opponent. Otherwise, it’s ballroom dancing with fists and feet. Admit it – you’d watch Strictly Come Dancing if there was a non-trivial chance you’d see a disgraced former MP beating the snot out of a racist reject from Big Brother.

Come on Mav, do some of that pilot shit!

Wait, that might be the wrong 80s movie

As the Goose is played, the Elephant swaps into the red player’s deck. The only way you can set up an attack in Onitama is through understanding the dance – to know where it is safe for you to step, where your opponent is likely to step in response, and hopefully be there ready to deliver an unexpected side kick when they arrive. The cards in Onitama may have all the obvious charm of a crossword puzzle, but they lend a surprising amount of thematic heft to a game that is otherwise completely abstract.

I call this ‘The Bojack’

As pieces move in and out of play, a narrative emerges. See here – with red we have an eager student, ignoring the example of the master, and charging into battle. The opponent master, seeing a teaching opportunity, strides carefully and serenely forward.

The Elephant Mantis is the most feared of all the insects

The student carefully eyes up the available options on the table. Elephant and Mantis must be considered against the zone of power presented by the opponent. The student must step into the areas where the master is weak, and in doing so will push the master to those areas where the student is weak. All of this must be eyed up against the recycling flow of actions available to each – when a card cycles into active use, all of those zones change once more. You’re constantly evaluating the board for now, for then, and for the now after then.

Trust in the quality of what you know, not quantity

The student sees the master cannot project an attack directly ahead, and so nimbly performs an elephant shuffle (make up your own names, it’s fun) to whirl directly ahead, ready to strike an incapacitating blow when the moment is right.

Doing a Dumbo

The master however is performing the same spatial evaluation, noting that the student is weak on the right side. A Goose Roll takes him safely out of danger, and in a position to side-kick the upstart’s teeth out of their insolent mouth.

Sweep the legs!

In the process, the student realises too late that not only can they not attack the master, but the master can attack them at will. There’s only one move that will take them out of danger. Everything else will result in the master taking the piece and removing it from play. However, the master must be mindful of what happens after that – a student may fall back, offering themselves up as a sacrifice to lure the master into the fists of another. In this case, no – the red student performs a cowardly Horse Fall and slink off to the left. The lesson is learned – humility is its own form of respect. However, a blue student sees the opportunity to strike, and moves into attack range.

But sensei, I can beat this guy!

The red student, presumably humbled and a little embarrassed, decides that it’s time to engage in an act of confidence building brutality. A whir of feet later, the blue student lies on the ground. The student behind the fallen leaps forward to subdue the aggressor.

Pieces in Onitama don’t represent access to abilities and attacks – they represent control points in the battle. They’re nodes that exert a suppression field around them, and being able to remove a piece means that your freedom of movement is expanded. While it may be difficult to pin down the master for a strike, the more students you can knock out of the match the more likely your own master will be able to stride over to the opponent’s temple arch.

Avon calling!

Constantly what you are doing is shaping the safe places of the battle, to funnel opponents into those places where you’re more able to land a hit.

While you can certainly create weak positions in Onitama it’s rare that a position is ever entirely lost until an opponent has an overwhelming numerical advantage. This is not like chess where you can have lost the game fifteen moves back. This is a far more emergent, organic experience of tactical positioning that changes depending on the fighting styles available. Onitama is a game that mirrors the properties of water. You must be shapeless, formless like water. When you pour water in a cup it becomes the cup. When you pour water in a bottle, it becomes the bottle. When you pour water in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Water can drip and it can crash. Become like water, my friend.

STRIKE FIRST. STRIKE HARD. NO MERCY.

Most of the cards in Onitama focus on the comparatively workaday one-square styles. These create a certain kind of game where you never get an opportunity to strike without getting up close to an opponent. A set of five cards here creates a melee, where aggregate positioning is the tool you need to master. You need to focus and shape your aggression into a propagation wave that cannot be counteracted. This is the pragmatic martial artistry of real life.

Fear does not exist in this dojo, does it?

A few cards though introduce more esoteric options. These permit aggression at a distance – this introduces a more ‘Crouching Tiger’ vibe to your options. You can lure an opponent into taking a piece only to HIYA launch a flying tiger kick right at their dumb face from two squares away. The Dragon conjures up mental images of flying roundhouse kicks. The Crab elicits the showy athleticism of the Matrix movies. When these cards are in play, combat becomes more dangerous. The real joy comes in juxtaposing sedate manoeuvring with moments of more cinematic Kung Fu.

Too much advantage, your dojo.

It’s really the set of cards you deal out that defines what a game of Onitama feels like. Every different set will create a different battle, with different risks, and different opportunities. That’s why I say Onitama eliminates fixed starting strategies – they’re too dependent on a phenomenal element of combinatorial explosion to be remotely feasible. Like Takenoko, this is a game of reacting to situational complexity.

It’s also the random set of cards that eliminates the need to build explicit mastery. Mastery over what? The only thing you’re shaping is the battleground and the zones of danger. You can see how that works from the cards, you don’t need to learn a complex set of techniques that chain together. The chains available depend entirely on the board, and the cards that are in play. It’s not that you can’t get better at Onitama, because you can – it’s that you can’t simply learn the accumulated wisdom of the masters and expect to triumph. A savvy novice can absolutely beat a wizened veteran, making it a far more egalitarian game than either Chess or Hive. It’s a perfect information game that still manages to permit the leveraging of secrets for those that can truly comprehend the options in front of them.

Just as you’re getting a bit tired of the options you have available to you in any individual game you’ll find that perfect moment arises – the one where the cards combine in such a way as to let you push an opponent into a position of weakness and then strike, taking them out and winning the game. Games of Onitama don’t drag on – they end, usually, before one player even realises what has happened. Sometimes, even before both players know.

An enemy deserves more mercy!

It’s a really, really nice game.

There are though a couple things that keep me from being too effusive in my praise. The first is that for all the tremendous complexity Onitama manages to wring out of an incredibly simple ruleset, there is a point where the challenge renders down to a task of optimising spatial awareness. The cards, for the most part, aren’t very different from each other and while some offer more interesting options than others, they are all variations on ‘move to a square’. If you imagine each card’s movement profile overlaid onto a heat-map of the board, all that’s changing is the density of the hot patches. Don’t get me wrong, you’ll get a lot out of that variation – but after a while it’ll start to feel more than a little bit samey. I’d like to have some more advanced cards that could slot into play when things get a bit stale. Why can’t I move to a square and set it on fire for a turn? Why can’t I have a card that does a move then attack? These would dial up the complexity, but they could be kept away from the base set and folded In only when someone feels the base game starting to lose its lustre. The good news here though is that it’s a simple enough game that you could house rule your own variations, but we review games as they come out of the box rather than how they might look after our cack-handed modifications.

The second thing is that for all its elegant simplicity I do feel myself hankering for the pieces to be more interesting than just nodes on a graph. The masters differ from the students only in terms of value – they aren’t meaningfully better in active play. This dovetails with my point above – it would stave off the point at which Onitama becomes a largely solved proposition. I’d like to have reasons to move a piece rather than just ‘that’s the piece that’s closest’. In abandoning that aspect from Chess, and indeed Hive, Onitama loses something in terms of the depth of strategy it offers. Again – it needn’t be something that detracts from the base game, but for those looking to layer in a new challenge that would go a long way to continually adding reasons for people to bring it back to the table. As it is, once the novelty of the shifting movement patterns wears off there isn’t a lot to keep you coming back.

It does feel a little bit churlish to even bring yo these points though. Nobody plays chess and says ‘This’ll be great if they ever get around to releasing some DLC’. It’s just I think Onitama comes with an in-built limit on its strategic complexity. Chess gets better the more you master it – it becomes deeper, the challenges more intricate. Onitama begins as a more obviously resplendent game, but time and familiarity will dull that shine because there is a harder and lower ceiling that defines where the complexity can go.

Don’t let that put you off though – Onitama, out of the box, is a lovely game that will offer you lots of challenge without necessitating you do a pile of homework before you can appreciate it. The point at which you’ll have meaningfully mastered the game is almost certainly outside the time period you’ll invest. Unless you’re planning to go into Onitama with all the focused obsessiveness of a budding chess grandmaster, you’ll find it a continual joy to play.