| Game Details | |

|---|---|

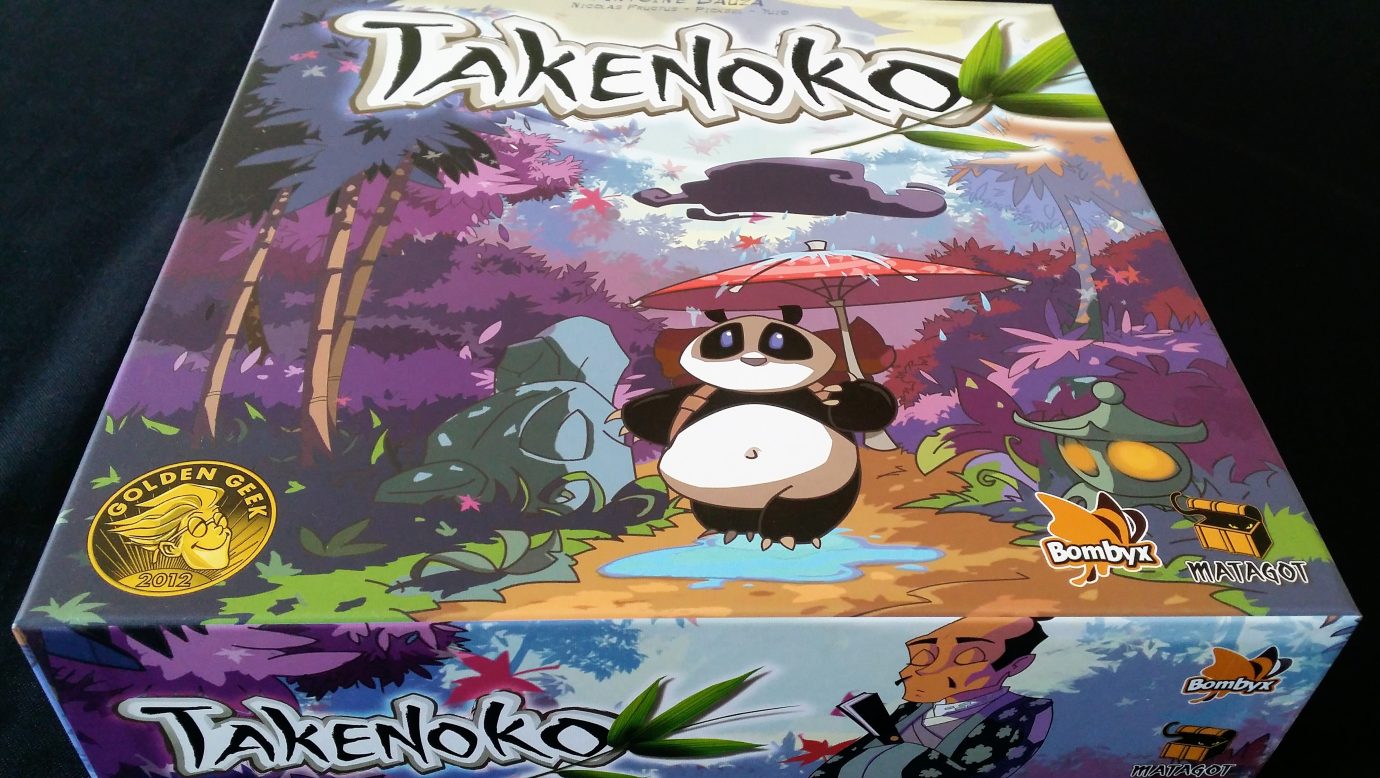

| Name | Takenoko (2011) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.97] |

| BGG Rank | 390 [7.21] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Antoine Bauza |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Hexes in Autumn

Panda eats the bamboo shoots

Calming consumption

Let me tell you about a little game called Takenoko. It is a game much maligned, despite its relatively lofty position on the Board Game Geek rankings. Shut Up and Sit Down dismissed it as a nopener – a game so bad that it should be considered the opposite of a gateway game – a gatekeeper game, if you will. Others have denigrated it as an exercise in frustrating randomness, or as something more akin to water torture than an enjoyable gameplay experience.

You’ll spend a lot of time going ‘oooo’ when you get this game.

Everyone agrees the game is absolutely beautiful, made up of a peculiarly lovely set of components that come together to create astonishingly pretty game states. However, as to whether it’s fun to play, opinions differ.

Forlorn little game

Who can know your spring-time charms

Lovely like the wind

Takenoko goes out of its way to immerse you in its theme – the artwork is gorgeous, and the physical tactility of the pieces is a joy. The instruction manual even comes with a little comic explaining the back-story, such as it is.

This is a Batman crossover that nobody would see coming.

The emperor of China has visited the Emperor of Japan, and as a royal gift has bestowed upon him a giant panda. The panda makes its way into the royal gardens, where the gardener is growing rich, tall shoots of various bamboo strains. The panda eats the bamboo, and the gardener grows it. Everyone around the table is playing both roles and that of the garden itself. It’s very peculiar and abstract and self-referential. And so very lovely:

Eeeee!

Oh my god look at that Panda! Isn’t it just the cutest? And look at the gardener – isn’t he just adorable? The love and care and attention here is palpable and seems so sybaritically unnecessary. You don’t need either of these things to implement what scant game systems are present, but oh my God they just charm the pants off of you.

Beautiful game board

Like sun on a winter day

You warm and nourish

Takenoko, like most games, proceeds in turns. Each turn, players will take two different actions, marked on their player sheet with little wooden tokens. Most turns will have weather effects, which impact on the game in various ways. Some weather effects allow you to take three actions, some let you double up on the same action, and so on. We roll a die for this at the start of our turn, allocate our actions, and then carry them out:

Even the tokens feel nice

Since we are the garden, we can expand – pick three tiles, choose one, and place it. If that tile is adjacent to the central pond, or is otherwise irrigated, bamboo will grow on it. Or since we are the water, we can irrigate – take a long blue piece of wood from the stack and place it along the edges of our garden tiles. As long as they reach the central pond, all tiles along their edges have water. Since we are the gardener, we can move in a straight line around the board. Wherever we land, we grow bamboo on that square, and each adjacent square of the same colour. And since we are the panda, we can move in straight lines to eat the bamboo on the square upon which we land. And finally. Since we also are the Emperor, we can take an objective card to complete. When a certain number of these have been completed, determined by number of players, the Emperor arrives to survey our work.

I prefer the yellow fruit pastiles too.

We begin the game with three objective cards – these are our scoring conditions. They’re secret to us, but we complete them by having the garden in front of us, or our panda stomach, meet the criteria on the card. If we have eaten two pieces of yellow bamboo, we can complete the first card and return the bamboo to the supply. If we have four green bamboo shoots on a tile that is fertilised, we can score the third card. And if we can create the pattern of green and yellow shown on the second card, with all hexes being irrigated, we can complete the middle one. However, the state of the garden is ever shifting – we are only one player, and everyone has their own goals they’re working towards. Sometimes these harmonise. Sometimes they contradict. Regardless of how well our goals converge, we’ll each be leaving the garden in a state other than how we found it.

A shifting garden

Twists and turns like summer breeze

Never twice the same

We have two actions, most of the time, so we need to pick them wisely. Placing tiles is always wise, since it expands the flexibility our efforts. Collecting and placing irrigation is nice too, since it means that a larger proportion of the garden is available for growth. But moving the gardener is always nice, because the gardener makes the bamboo bloom. And while it may seem like the panda is inherently destructive, it’s always nice to move him too – he can ensure that the bamboo does not grow out of our ability to manage it. Growth and decay, birth and death, ying and ying. Every choice has its quiet value.

I’m going all in on a pair of yellows

Not all tiles are created equal – there are three special kinds of tiles that have different game effects. Tiles with a water source marked on them are ‘watershed’ and require no external irrigation. The panda can never eat bamboo from a tile with a panda enclosure. Bamboo will grow twice as fast on fertilised soil. Some tiles have these as inherent, intrinsic bonuses. We will also improve the garden as a result of weather effects, adding these elements to otherwise plain tiles as we struggle to meet our objectives

Sometimes I’d like to drown the panda in one of those ponds

When an irrigated tile is placed, it gains a shoot of the appropriate coloured bamboo. Tiles adjacent to the central pond begin with irrigation, but we’ll need to construct our own channels as the garden grows – tiles to begin with can only be placed orbiting the pond, but can expand further out as time goes by.

From a single seed

We will be using this effect, and the powerful influence of the gardener, to construct our landscape. We’ll be using the voracious appetite of the panda to keep it in check. And we’ll be doing this whilst being largely oblivious to the goals of our opponents. Our careful plans can be undone, without malice or even awareness, by the casual enacting of another player’s desires. We in turn can convert their dreams to ashes through nothing more malevolent than our own aesthetic whims.

Brave shoot of bamboo

Striking up through fallen leaves

Your world is all new

Over time the garden will grow.

Tend your garden

And it will become rich and fertile with the application of careful irrigation.

Seek joy in advertisity

Over time, objectives will be completed.

Three points of meditative glory

And each one will bring the Emperor closer to his visit.

Delicious

At which point he will look upon our hard work.

Big and long, just the way I like it

And benevolently smile upon our endeavours.

It’s all so pretty!

Each of us will be winners in a very real way, servants of the Emperor and the garden. But in a more genuinely real way, the player that has accumulated the largest number of victory points will be crowned winner.

You may have worked out some of the flaws in Takenoko already. As anyone that reads this blog regularly will know, I have a huge man-crush on every single member of the Shut Up and Sit Down crew. And it probably won’t come as a surprise to know that I agree with every single thing they said in their brutal review of Takenoko. I agree with everyone that says this is a terrible game that offers no meaningful opportunity for strategy. You can’t really play to win in Takenoko. You can make rough guesses at what your opponents may be trying to accomplish, but those broad strokes don’t permit meaningful decision making. However the nature of the movement system and the furious specificity of the objectives means that you often have to approach tasks from the side. You can’t place improvements on tiles that already contain bamboo, for example. So you might have to eat bamboo, improve the tile, and then regrow it. You might be turning a four shoot of bamboo into an empty tile, before fertilising it and bringing the gardener to bear.

You can’t get the grouped gardener objectives unless you precisely match the number and size of bamboo shoots. It’s not ‘four shoots of three or more segments’. It’s ‘four shoots of exactly three segments’. If your only way to accomplish that involves a fertilised tile you might find yourself banging your head against your own private water jug problem.

It can be intensely, deeply complicated to work out when you know your own objectives. It can look entirely random from the outside. If you play to win, Takenoko is a game that is like finding the very concept of frustrated impotence trapped in amber and preserved for all time. And my god, it’s boring too – you’re just moving things around a board in the hope that nobody will screw you up too much by the time your turn comes around again. It’s not a game of highs and lows. It’s a game of frustrated landscape gardening. It’s just an awful game.

Oh, Takenoko!

Your beauty masks a darkness

Hot rage like thunder

So don’t think of it like a game. It’s something else. Something deeper.

Look, I played my first game of Takenoko with the same mindset with which I approach every game. It’s a system to be learned. It has secrets that careful thought, observation and experimentation will unlock. And once I’ve unlocked them, I can use my knowledge to crush my opponents. Or, in co-op games, I can use that knowledge to crush the systems that seek to thwart me. I found my first encounter with Takenoko quite stressful. I kept saying, incredulously, ‘This is for eight year olds?’ You can work out, within a reasonable margin of error, some subset of your opponent’s likely goals. I consider myself a very smart guy, and I couldn’t meaningfully play this as a game of strategy that I could feasibly and effectively control. A game for eight year olds? Only if they’re the bastard offspring of Stephen Hawking and the Mekon.

But then I tried something different. I relaxed into the theme.

And you know what? There’s something fantastic in that. Don’t think of Takenoko as a game. Think of it like a toy. Think of as a tool for facilitating a kind of tactile meditation. Those gorgeous components aren’t an unnecessary frippery – they’re a key element in the inherent satisfaction that goes along with cultivating a physical garden. This isn’t a game of strategy and mastery of systems. It’s more like tending a Bonsai tree. You just need to approach the game on its own merits, and abandon your assumption of how a modern board game should play.

Some have said that Takenoko is a game that stresses the tactical at the expense of the strategic – that it favours short term planning over longer term considerations. I’d go one step further. I’d say that Takenoko completely eschews that whole dichotomy. This isn’t a game about taking action. It’s about careful reaction. You are not an agent that brings change in the world. You are that which is being acted upon. It’s a game about being in the moment, and assessing the world in front of you before choosing the path of least resistance that brings you closest to your goals. The game systems are a reflection of chaos theory, encapsulated in a tractable package that anyone can understand. Those hidden objectives your opponents hold prevent you from playing aggressively, or even particularly intelligently. So if you can’t do that, all you can do is try to shape the chaos in a way that works in your favour.

This is a game that requires depth of character, not depths of strategy. If you can approach it in that spirit, I think you’ll find it very rewarding.

Funny little game

More to you than meets the eye

Peace can blossom here.

This may be an unusual conclusion to reach about the game – most reviews I have seen tend to concentrate on its merits, or otherwise, as a gaming experience. I think it’s more helpful to think of it as experiential gaming. Everything about it is designed to pull you into the moment, and to create the ambiance that permits you to simply enjoy the downtime between turns. It’s about watching how the garden changes and evolves and grows, not about ignoring the here and now in favour of a grand master-plan that you are ceaselessly constructing in your mind. The game can be boring, in the same way that meditation can be boring. You’re expected to bring something of yourself to the experience, rather than offload the responsibility entirely onto the game.

I suppose you expect me to clean all this up?

So, I agree with the criticisms that Takenoko makes for a poor game, and I even agree entirely with Matt Lees of Shut Up and Sit Down that this is a game that could actively discourage new gamers. For an introduction to board gaming you want something fun, visceral, and full of nascent life memories Takenoko is none of those things. However, I think Takenoko is a fascinating and interesting game if you can just shed your expectations of systemic mastery. It’s not a game of great, sweeping moments. It’s a game of passively waiting for the right moment. That too has value.

Game, we leave you now

Wiser for our knowing you

Calm, like falling snow