| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | A Game of Thrones: Hand of the King (2016) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Light [1.23] |

| BGG Rank | 1958 [6.60] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Bruno Cathala |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

If there are unsung heroes of the Game of Thrones television team, it’s certainly the casting department. Lena Headey is amazing as Cersei. Jerome Flynn is magnificent as Bronn. Charles Dance is mesmerizing as Tywin Lannister. The casting team have taken the tremendous characters that are threaded through what is realistically a mediocre bit of fantasy fiction, and given them to people that are objectively excellent at the roles. I can’t see the names without visualizing the actors, and that’s a hell of an achievement. These actors don’t just play the roles, they inhabit them. There might have been people out there that could play Jaime or Ned Stark better, but I’d never be willing to even give them the chance to prove it. Nobody else could ooze the unguent charm of Varys like Conleth Hill. Nobody else could embody the nihilistic fatalism of the Hound like Rory McCann.

When you play the Game of Thrones etc etc blah blah

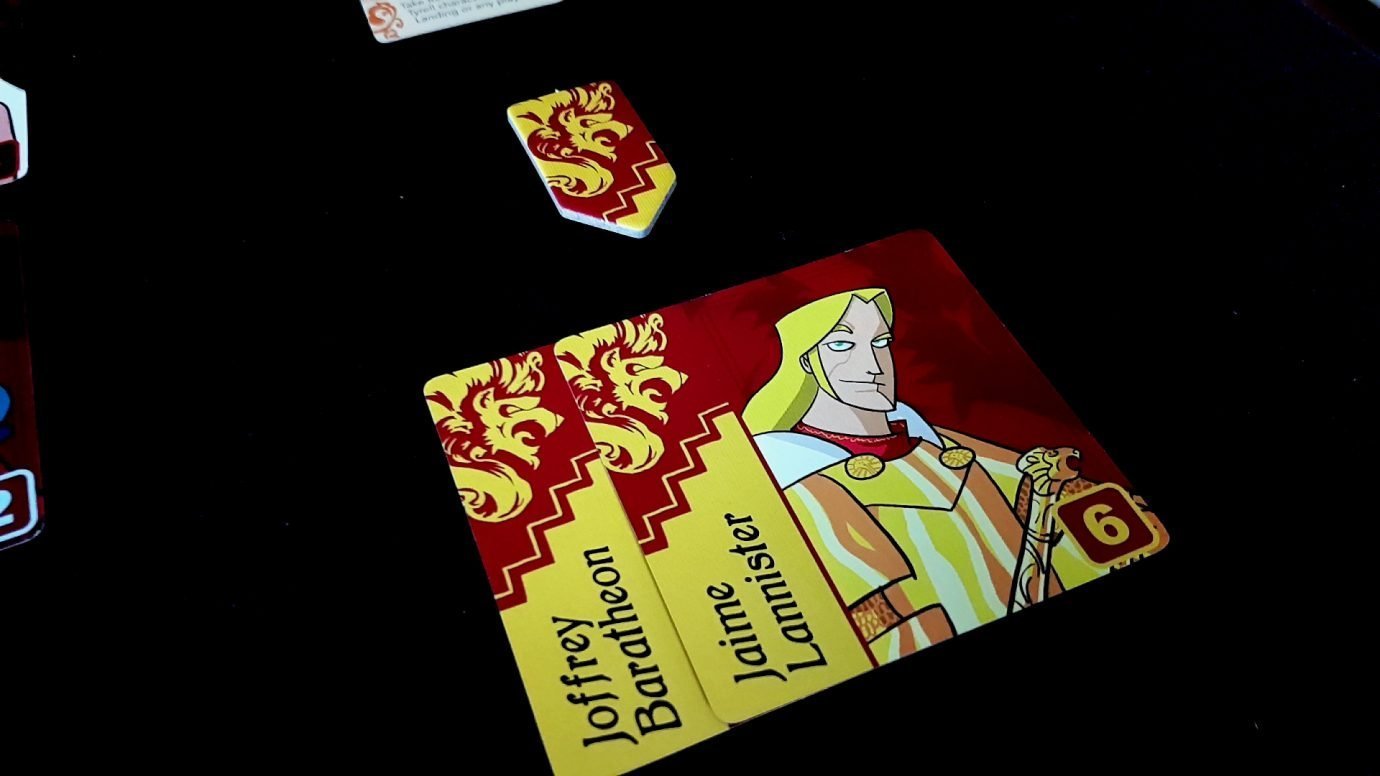

The stellar casting is responsible then for a fair bit of nameless discomfiture when it comes to playing Hand of the King. The art is inspired by the books and as such it doesn’t always reflect how I have come to think of the characters. It lends everything a vaguely budget look that gives the forcible impression that somehow you’ve ended up in the Tesco Value version of the Game of Thrones universe. The art isn’t bad – at least, not uniformly. It’s just not quite the stellar production values I would expect from a game set in world of rich and vibrant personification. The artistic direction, and attention given to individual characters, is uneven. You get used to it, but it’s a little bit distracting in the short term.

Weird

I mean, look at Theon – he looks like the bastard offspring of Dracula and Vince Vaughn. Someone seems to have forgotten Sansa Stark has a nose. Margaery Tyrell had so much time spent on expanding her chest that her face seems to have been forgotten in the process. It’s all perfectly serviceable, and your mind’s eye will compensate for the deficiencies in any case. It’s difficult though to fully immerse yourself in the conceit around Hand of the King without it being effortful. Even if you’re a fan of the books as opposed to the television show, I suspect none of these characters will look the way you have envisioned them.

North or South they sing no songs for spiders

If you persevere with this though you’ll find this is actually a very tight game of political jousting that simulates a considerable amount of the febrile and shifting power brokering of the Seven Kingdoms. You and your fellow players are unnamed High Lords, jockeying to become Hand of the King with the help of the sinister Varys – silken spymaster of the Red Keep. Your job is to recruit supporters from the great houses in sufficient numbers that you can claim their banners for yourself. The plotter with the largest number of banners at the end gains the dubious distinction of being chief advisor to the King. It’s a job with a great benefits package but with an average tenure trending towards the vanishingly short. It’s a job not unlike being Don of a contentious mafia family – you get the biggest share of the rewards, but you’ll almost certainly come down with a serious case of lead poisoning before your chair is even warm.

It doesn’t matter though – this is the job you want and you’re damn sure it is going to be you that gets it. Application procedures in Westeros are fractious and the only thing worse than being Hand is being the failed candidate for Hand. You’ve got Varys on your side, but so does everyone else. The loyalties of the spider are only ever briefly rented – not even the Lannisters can afford the price to purchase them outright.

King’s Landing is made up of a six by six grid, within which Varys stalks with his whispers and exhortations. Each player in turn names a direction (up, down, left, or right) and a house to which Varys should move towards. We might say ‘Targaryen, right’ and Varys will move to the farthest most representation of that lineage. You’ll pick up all members of the house that he moves over in the process. Whomever has control of the house gets the banner associated. If the cards you just took give you an equal or greater number of characters than any other player, the support of the house is yours – at least, temporarily.

Seem to be more dragons around than you might expect

‘Lannister, up’, a player might say and Varys will oblige – perhaps gathering up Jaime Lannister and Joffrey Baratheon in his embrace. The number at the bottom right of each card shows how many of that house are represented in King’s Landing, and as such that determines how contentious the battle for influence might become.

Do I really need to keep Joffrey?

‘Greyjoy, left’, says another player and gathers up Balon and Rodrick Greyjoy. Each player has two representatives of each house now, and as such each player has a banner they control. The game continues in this way until Varys can no longer make a legal move, at which point the banners are counted and a Hand proclaimed.

If you’re the person that picks up the last card in a house, you get to claim one of the six random companions dealt out to the side of King’s Landing. These have powerful, but intensely situational, benefits. They can completely upset someone’s plans, or simply give you the extra momentum you need to dominate proceedings. They’re not overly powerful, but essentially become a lever that at the right time and the right place can change the shape of the future. As such, collecting a companion is as much about timing as it is about the powers they make available.

Hodor? Hodor.

Consider Hodor, for example. If you have an opponent that has claimed Bran Stark and the Stark banner, you might find power reverts to you if you claim Bran from them. Ramsay Snow might let you convert a perfect turn for your opponent into a perfect turn for you. Sandor Clegane might be just the thing to prevent anyone else competing for a house that you’re currently dominating. You use their powers immediately though – you don’t get to hold them in reserve until they become useful. There are times when claiming a companion at the wrong time might very well be the worst possible thing you can do.

The thing that makes all of this work is in a throwaway remark I made above. The person that controls a house isn’t the one with the greatest number of characters – it’s the one that just took a card that gave them a greater or equal number of characters. Ties in Hand of the King are resolved in favour of the aggressor, and that turns a mathematical process of set collection into something an awful lot more difficult to manage. The decisions in Hand of the King are tricky because numerical superiority is not enough – you need overwhelming superiority and to make sure nobody can challenge it. You’re rarely safe in the support of a house. If you do spend all your time and effort locking up one set of supporters you’ll just find that all the others have been divvied up in your absence. The alliances you form in Hand of the King are awfully fragile. All it takes is one careless move on your part for your entire base of support to melt away. You spend a lot of time in Hand of the King not obsessing over your choices, but the consequences of your choices. That’s just what you want in a game like this.

In a two-player game, the decisions are difficult but manageable – it’s a race for optimisation. You want to move in such a way as to give yourself maximum benefit while exposing yourself to minimum risk. That’s always harder than it should be given the relative dearth of options you have on your turn. Consider this random layout of King’s Landing:

A fresh set of intrigues

As the first player you’ve got a relatively safe move – ‘Tyrell, left’ and you’ll gain two of the three Tyrells and the next player won’t be able to claim more than one house on their turn. Anything else will give your opponent two cards. Seems safe, seems sensible, and so you do that – claim the two Tyrells and leave your opponent to suffer. Got it all sewn up, mate – Tyrells have bent the knee.

Except… well, what if the Ser Loras companion is out in the companion area? He lets you take Renly Baratheon or any Tyrell character from King’s Landing or any play area. Whoever gets the last Tyrell card is actually going to win Tyrell support because that’s what Loras permits them to do. Worst of all, you won’t have any recourse. Your only option is to be the one that gets Olena Tyrell from King’s Landing, or to grab the Loras card for yourself. You didn’t actually win a victory there – you exposed yourself to risk, and the risk is considerable. You’ve just made it so that you’ve almost certainly lost the Tyrell house unless you prioritise getting a card that you only need because someone else might take it. Argh. You’ll be paranoid for the whole game about putting your opponent in a position to claim the Tyrells.

The clever thing about this is how it gives each house its own flavour. You want to recruit Tullys, Tyrells and Baratheons in small numbers because that ensures you retain the possibility of claiming the house back should someone else make an attempt to deprive you. That is unless they could sweep up the remaining characters in a single move otherwise. Small houses are easy to claim but also intensely swingy. Large houses are more resilient to take-over attempts because there are so many members to solicit. Each of the houses will seesaw, but they all do so in a distinctive way.

Your opponent meanwhile has their own problems, because they’re performing the same mental calculations as you but from the perspective of how to protect their own political ambitions. You need to see the risks, and often that hides from you the potential rewards. You’re playing a game that is intensely defensive because the stakes are high. One mistake can unravel everything you are working towards and momentum is both a critical aspect of play and an intensely malleable property.

Bend the knee, my lords.

And this is fine – it’s a decent, solid and entertaining game for two players. It’s a duel – a joust, even. You direct your enemy where you want them to go and don’t follow where they are leading. Brianne of Tarth would approve. The decisions you make aren’t especially nuanced since this is at core a mini-max challenge. They are though definitely satisfying.

It’s at higher player counts though that you really see this start to reveal itself at its best. At two players you need to worry about how your opponent will respond to your actions but you have limited ability to really mess with their plans. All you can do is go where you hope they don’t want you to go. Three or four players though, you get to practise intrigue.

With this I’m not even talking about the one eyed raven tokens that you use to have secret conversations with people about your plans. I’m talking about the way having a third or fourth player enriches the decisions you can take. You’re no longer just thinking ‘What do I want and how do I get it’. You’re thinking ‘What does the player before me want, and how can I put the player after me in a position to threaten it?’

Hand of the King with two players is well symbolised by Varys, but at three players you really should switch out his card for Littlefinger. It becomes much more Machiavellian, and as a result much deeper.

Cheer up Rickon. Might never happen.

Consider the scenario we were discussing above – our first player (Pauline) has two Targaryens. We have two Lannisters. Player three (Jasmine) has two Greyjoys. ‘Stark, down’, says Pauline and picks up three Starks for her trouble. She controls two noble houses, and you’ve got very little in the way of good options for yourself.

But…

Do you have an option you could maybe set up for the next player? Let’s say you decide to give up on Targaryen and Stark characters. If you could maybe engineer it so Jasmine could get a couple of either of those you’d have both of them fighting over a house you have abandoned, hopefully giving you free rein at the others. Everyone is making the same decisions after all – and if you set someone up with an obvious opportunity to claim a house from an opponent then they’ll almost certainly take it. Unless of course they don’t follow where you are leading…

Those are the kind of decisions threaded through the higher player counts of Hand of the King and they turn a decent game of card play into something genuinely more compelling. You could lose yourself in the battle of wits that’s sparked off by the random arrangement of characters put before you. If everyone else is doing the same thing you’re could find you spend as much time evaluating the actions of others as you do making decisions of your own. At two players it’s a puzzle, but at higher player counts it’s psychology.

It’s important to emphasise that despite all of this Hand of the King is a very light game – both mechanically and in terms of the number of actions you’ll take. It’s asking you to make deep decisions within a shallow possibility space and as such it’s a game that is bigger than its scant setup can really support. This creates the bizarre circumstances where it’s an unquestionably better game at higher player counts but really only on paper. It creates the opportunities for allowing you to set up betrayal and intrigue but it doesn’t give you the time to really immerse yourself in the options. You can’t hatch long term plots – your scheming literally lasts as long as the length of your turn. Within thirty-six cards there’s only so much that’s going to happen with three or four players. As such while you can get into the head of your opponent you can’t spend a lot of time making yourself comfortable. And that’s a shame. I like it in there.

A larger political stage would have let this happen more effectively, but you don’t have that. The comparatively shallow game of parry and riposte to be found in two players is thus more satisfying simply because there’s room to manoeuvre within that context. The manoeuvring isn’t particularly edifying, and the decisions aren’t particularly interesting, but you do at least have a chance to make them often enough and with sufficient impact for the game to have a more easily appreciable heft.

The problem is that those decisions don’t feel nearly as satisfying with three or four players. You make fewer of them, each is a lot more interesting, but ultimately at the end you are too much at risk of the churn of King’s Landing. As such, the intrigue is unsustainable and the dueling is less measured. It still functions effectively, it’s just not optimal.

If you’re looking for a completely solid two player game, Hand of the King is definitely fine. If you’re planning to play it with higher counts I think you’re just going to be frustrated – not by the game itself but by the fact you can’t really play the much cleverer game you can see struggling to get out.