| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Hanabi (2010) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.69] |

| BGG Rank | 537 [7.04] |

| Player Count | 2-5 |

| Designer(s) | Antoine Bauza |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Hanabi is a game that belongs in the collections of game designers the world over. Not because it’s fun, because it isn’t. Instead, Hanabi is a cautionary tale in the dangers of believing innovative design by itself is sufficient to make a game worth playing. Hanabi is a masterclass in a tiny box. Pay attention to the lessons it teaches – they’ll inadvertently make you a better game designer.

A box of delights?

As usual, I feel the need to preface my review here with an acknowledgement – mine is a minority opinion. You’ll find almost universal praise of this game if you look for reviews. I know, because that’s exactly what I did before I sat down to write this one. I don’t usually do that, but I felt a need to find someone out there that agreed with me. Failing that, I felt a need to at least understand why so many other people rate this tedious time-sink with such reverence and respect. I failed on both counts. Often when I don’t enjoy a game I can find someone that can enthuse about it in such a way as to make me think ‘Oh sure, that makes sense’. Every review I read of Hanabi just left me feeling more mystified. At no point did I think ‘Oh, that’s what I’m missing!’. Every single review just made me think ‘Oh, I already knew all of that – and you still like it?’.

Most games these days have gone through enough design iteration and playtesting to have worth to someone. Hanabi comes from Antoine Bauza – and there’s a man that knows his game design. It won a Spiel des Jahres so it has achieved critical success in the most prominent ceremony of the industry. It’s sitting in the top #250 on Boardgame Geek so it has broad appreciation amongst board game connoisseurs. I look at all of this in the same way a dog probably views interpretative dance – a baffling and frightening display of incomprehensible synchronicity. My response is going to be much the same – to growl and bark and whine in a visceral display of upset and alarm.

Here’s how it works. Every player is dealt a hand of cards. These contain a representation of coloured fireworks with numerical order. In turn, players choose one of three actions.

- They can play a card down, either starting a new firework display or continuing one that already exists.

- They can discard a card in their hand, replacing it with one from the draw deck.

- They can give a clue about a card someone else has in their hand.

Wait, give a clue? What?

See, this is where I think Hanabi confuses people – the next bit is going to make you say ‘Ooo that’s clever’ and from that point on you’ll be hooked. You’ll be swept away by the cleverness at the core of the game and you’ll lose sight of the key truth – that Hanabi is not fun. Games are supposed to be fun.

Here it is. Here comes the hook. You’re each holding a hand of cards. But the thing is… you’re all holding them backwards. All you see is the back of your cards – you can see clearly what everyone else is holding. Your own hand is a mystery to you, and that’s the hand from which you’ll be playing cards down when you make a choice.

‘I was learning your tells’

I know, I know! It sounds awesome. And it really is a lovely idea – suddenly this is a co-operative game where nobody can quarterback and everyone can contribute. It sets up a logic puzzle of intricate deviousness that everyone has to work together to solve. And then it adds just the right number of tools to let you untangle that puzzle while keeping it challenging.

Giving a clue you see is an action bound up in legislation. You can indicate either the number on a set of cards, or the colour. You can only do one number or colour at a time, and you have to be fully comprehensive in your clue.

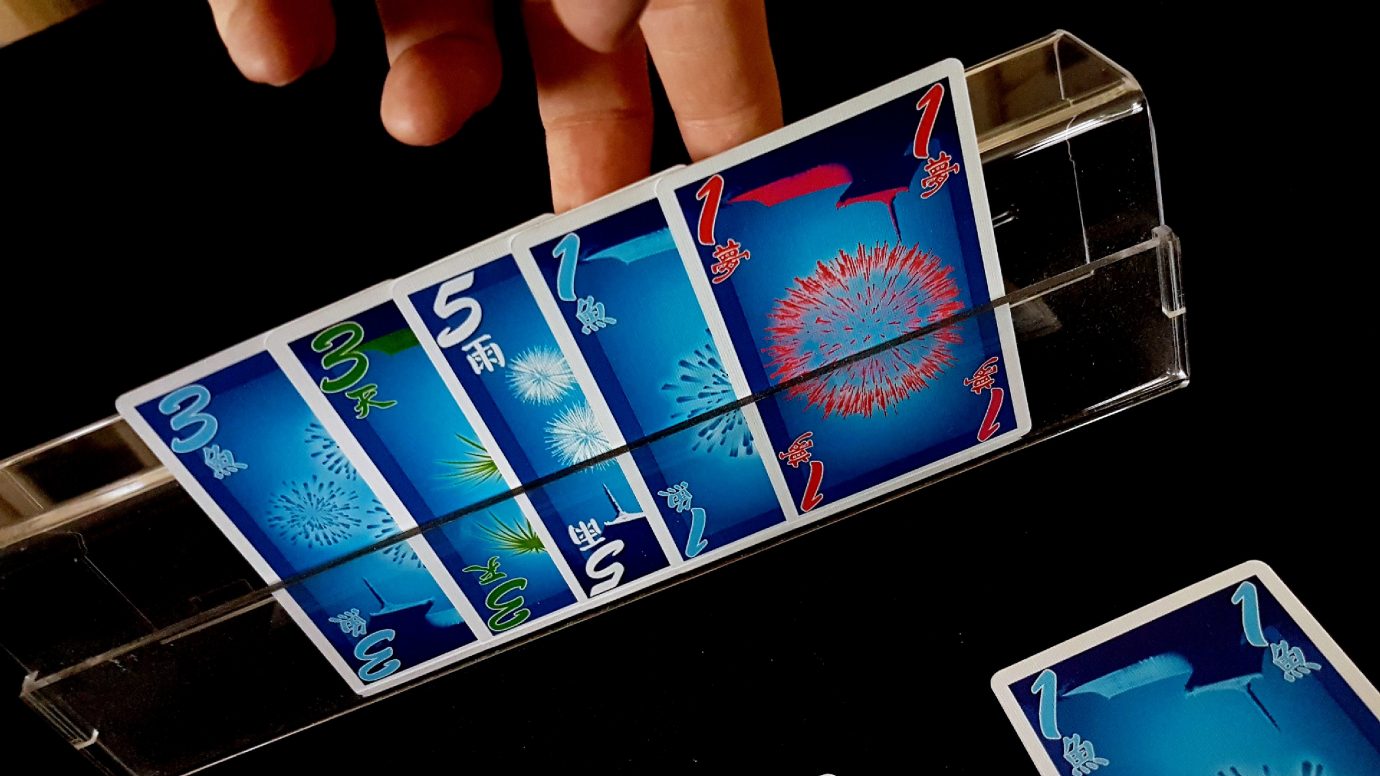

Look above – we could say to the player across from us ‘You have three ones’ and then tap each in turn. Or we can say ‘You have two blues’ and tap the third and fourth card. ‘You have two greens’ and tap the second and fifth. Whatever we say, it costs us a token to say it and we only start off with eight of them.

Tick tock

If we want more tokens, we need to start discarding cards – and that means we might not be able to make a firework display at all. Remember, we don’t know what our cards are – we have to rely on the clues we’ve been given to assess value. Rarely do we have fully perfect information – every card is a blend of imperfection of varying recency.

The grim inside of the box

Playing a card has to either begin a firework display (putting down the one of a colour), or continue it (putting down the next number of a colour). If the card played doesn’t do either, one of the fuse tokens are discarded. Three strikes and the game is over – the fireworks explode in a disappointingly premature mess reminiscent of a teenager’s first awkward sexual encounter.

It’s the world’s least exciting firework display

At the end of the game you get points for how well you’ve constructed the display – you add up the largest value card for each of the colours and that’s your score. You then compare that to the score chart which explains how well you did – less than five points and the crowd spits and stones you as you try to escape to your cars. Twenty five points and the rockets red glare will warm the hearts of even the stoniest pyrotechnophobic. And that’s it. That’s the game.

Also an unexciting firework display

When I last played this with a group, one player at the table would constantly ask me what I had misunderstood about the game. He was convinced I was missing a whole section of rules that would turn this experience in collaborative teeth-pulling into actual fun. All the other games we’d played, he implied as a result of his repeated inquiry, had been fun. This was – this was something else. Something infinitely inferior. And he was right. Hanabi is not a fun game. It’s an interesting design, elegantly implemented. But that’s all it is.

The theme is exploding fireworks and I think even the most ardent Hanabi devotee would admit that the implementation is listless at best. It’s an ugly game – a game where the design aesthetics are only half-hearted. When you think of other Antoine Bauza games like Takenoko it’s impossible not to be disappointed. A game about fireworks should be visually stunning. It should make the table into artwork. There are so many games we’ve looked at on Meeple Like Us that are physically beautiful artifacts. Hanabi by comparison looks like an own-brand pack of cards from a discount budget supermarket.

I don’t need games to be beautiful to enjoy them though – Scrabble remains atop my ‘best game ever’ list despite looking like the aftermath of a serial killing in a library. What I need is for them to be an enjoyable way to spend some time. I found out last week that my eyes have degraded to the point I need varifocal lenses. I am officially an old man and every minute I spend not enjoying myself is a minute I’ll resent on my imminent deathbed. I need my games to pleasantly pass the time. Hanabi doesn’t do that either. It’s like a multiplayer Sudoko puzzle where everyone has replaced cheerful chatter with ultra-defensive passive aggression.

Collaborative games live and die on the energy they create in the room. Hanabi has that peculiarly Codenames philosophy of collaboration – that creating the circumstances for intense reflective silence will carry the day. It really doesn’t. Instead, what you have to do is lean on Hanabi’s curiously tentative get-out clause. It says:

‘Communication (and non communication) between the players is essential to Hanabi. If you follow the rules closely, you can only communicate with your teammates when you give them information placing a blue token. However, you can play whichever way suits you best: set your own rules regarding communication. You could always allow comments like ‘I still don’t know anything about my hand’ or ‘so do you remember what you have in your hand?’

Hanabi has no confidence in its own ludic setup and it puts the onus on you to correct the deficits in the playing experience. As such, a whole subculture of Hanabi players situate themselves across a wide spectrum of permissiveness. By which I mean ‘a spectrum of cheating’ – because there’s giving a clue and there’s giving a clue, right?

‘THIS CARD THIS ONE HERE HERE THE ONE I AM REPEATEDLY TAPPING is blue, and so are these two I suppose’

‘Gosh, I’ll pay the card you have so stridently indicated then!’

‘Hooray, everything is awesome now!’

The order, and intensity, with which you give clues conveys game meaning but if you’re giving away too much then the task is trivial. On the other hand, if you adhere to the strictest definition of the rules then there is no space within play where people can actually have social fun. You don’t collaborate, which is a terrible sin in a co-operative game. You can’t discuss the state of play because that will reveal too much game information. What social interaction happens in a game of Hanabi happens around it, not about it – at which point, why not just get rid of Hanabi and enjoy the company of your friends?

These two are ones.

So, a two then?

Perhaps the reason is that Hanabi offers an interesting puzzle? After all, companionable silence in pursuit of intellectual satisfaction is a perfectly good way to spend an evening. Even this doesn’t convince me because I don’t believe that Hanabi accomplishes its design goals well here either. Sure, it’s a neat hook to have a portion of the game state hidden from you but all you’re really doing is trying to remember what you’ve been told and rearranging your hand accordingly. As clues are given, you move cards into the position in your hand that reflects your understanding of state – ordered by increasing numeric value, for example, or clumped based on colour. Balancing the shared supply of clues is nice, but it’s also very limited because the deck comes with multiple cards of the same number and colour combination. While this makes playing the right card a challenge on occasion it also means there’s an abundant supply of discards, especially later in play. When all the ones have been played out and someone taps three cards and says ‘this is a one’ – well, they’ve just made three discards available at no risk.

In the end, Hanabi is a game of people pointing at your cards and you trying to remember what they told you. Every turn you either play a card that you’re sure is of the right colour and number, or get rid of one you are pretty sure is worthless, or tell someone something about their cards. Does that sound fun to you? It doesn’t sound like fun to me and my experience of play has borne that out.

And yet, there’s all that popular and critical acclaim. People love this game. As with Love Letter, as with Codenames, we here at Meeple Like Us must take up a contrarian position even when it feels like an admission of personal fault. Hanabi is clever, yes. It’s that tediously smug kind of clever though that I associate with the most braggartly first year university students and the worst kind of pub bores. It uses conspicuous cleverness as a way to mask over its deeper failings. It’s the kind of limited intelligence that mistakes a shallow pool of trivia for a deep well of actual knowledge.

I’ve found cleverness in Hanabi. I’ve found design elegance. Trust me, I’ve looked in this box. I’ve peered intently into its slim form factor. I’ve shone a torch into its corners. And for all my focused investigation of the interior I just haven’t found anything that could be passed off as fun.

Maybe my box is just defective. Excuse me, I’m going to check the contents in the instruction to see if I’m missing a key component. Other people seem to have been getting a much better game than I’ve been playing.