Table of Contents

Version Reviewed

English Edition (Abandoned Cabin, Secret Lab, Pharaoh’s Tomb)

Introduction

The Exit games don’t coddle you, but they also treat you with nothing but absolute respect. They are challenging scenarios purely because this is a series of escape rooms that simply trusts you’re up to the challenge. Harsh but fair, in other words. We gave them four and a half stars in our review, noting though that there is a certain amount of environmental recklessness that goes into buying a game where you ruin the entire thing as a result of occasional scalpel-precise vandalism.

Much of this accessibility teardown is going to cover very similar territory to that of Unlock – we’re not going to spoil the game and so we’re only going to be able to talk about specific instances obliquely. The observations here are indicative, and not necessarily exhaustive or even representative of the specific scenario you undertake. Future boxes will undoubtedly take creative licence with the concept and introduce even more varied accessibility issues. We can’t be thorough here, short of spoiling every Exit adventure that is ever published.

With that in mind, let’s get out of this teardown before we die in the attempt. The clock is ticking.

Colour Blindness

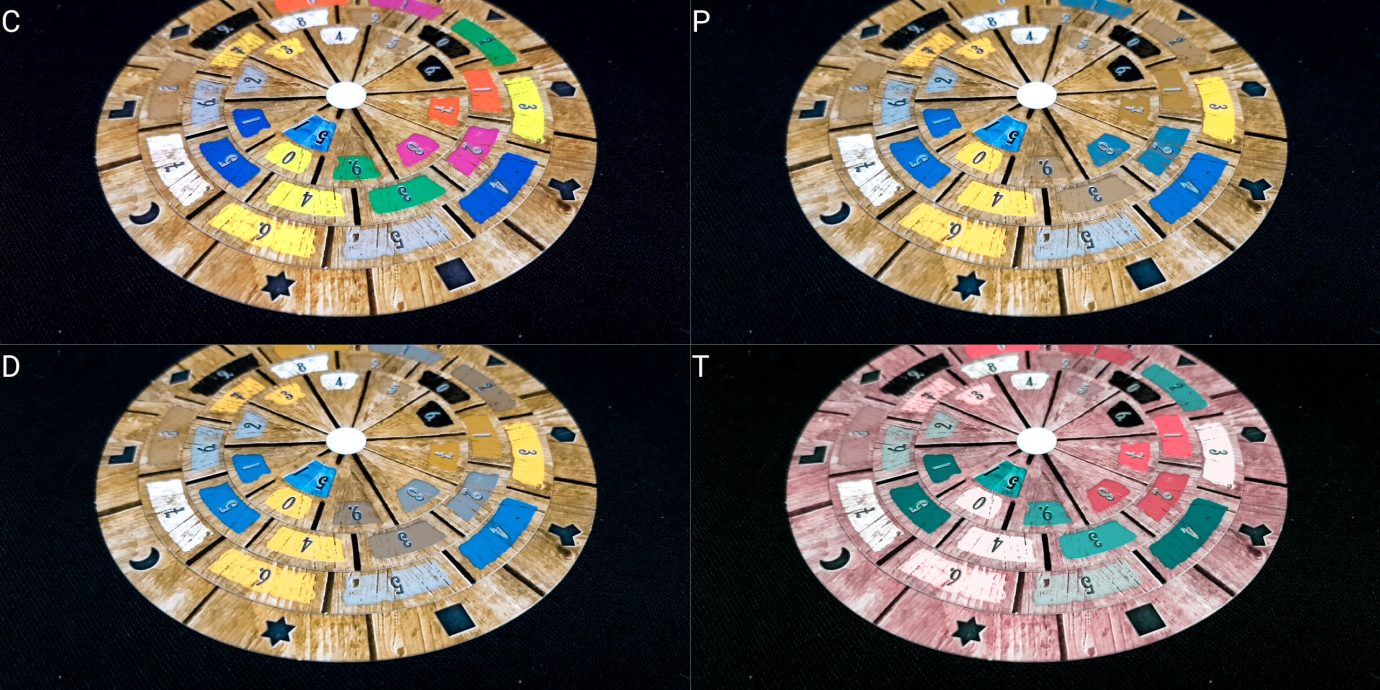

Colour is a very significant part of the puzzle solving, either as an important channel of information or the sole source of vital game data. Often it’s not going to be entirely obvious when colour becomes critical. You get to see the decoder ring as soon as you open the box so I’m not spoiling anything by showing you how they look:

So, yeah – good luck with that I guess, and especially with relating it to puzzles that might involve colours in a wide variety of ways. Some puzzles are specifically colour dependent. Some scenarios offer some more additional channels of information in the decoder ring, but that doesn’t necessarily translate into greater accessibility for the the game puzzles themselves.

Colour is used a lot in the Exit games. It’s even used in unusual ways that can manifest problems in categories we hardly ever get a chance to talk about here and still can’t. God, I really want to. THE STROOP EFFECT! Sorry. It’s just this is all SO INTERESTING.

As with Unlock this is going to be a puzzle experience that depends on a group – there usually aren’t puzzles to be solved in parallel but there are certainly puzzles that can be partially worked out before all the information becomes available. I can’t think of any puzzle that would be impossible for someone with colour blindness given good light, a magnifying glass, and a great deal of patience. I can think of dozens that will be far less intuitive or far more difficult to correctly solve. Unlike Unlock, you have a time limit you can easily fudge here… you can pause a stopwatch, for example, and then use the paused time to deal with colour disambiguation. Provided a group contains at least one person with full chromatic vision the puzzles will always be tractable. I still couldn’t recommend a game like this to someone with colour blindness, but I’m not sure any escape room is likely to be an ideal candidate in this category.

Visual Impairment

There are virtually no puzzles in Exit, at least that I can think of, where information is actively hidden from you. However, there are lots of puzzles where visual information has to be managed in complex and subtle ways. Occasionally puzzles will also stress visual faculties such as binocularity and stereoscopic vision. The game cards that represent the core of the experience are well contrasted, albeit with occasionally small text, but occasionally one of the ‘answer cards’ will require you to identify very small icons in order to progress to the correct, validated solution. In collaborative settings, a sighted played can do this without it impacting on the rest of the group.

More problematic is the visual scope of the game itself – while nothing is actively hidden, it’s also the case you’re occasionally examining relatively complex environments for non-specific information. Puzzle symbols may be encoded into the background or represented by something that needs to be enumerated through counting. Spatial relationship between cards occasionally comes into play, as does relating game components to non-obvious parts of the game state. Some puzzles are very text dense, others very number dense. Some require rotation of visual information, path-finding, path tracing, and the interpretation of information coded in busy visual environments. Some puzzles are only visually parseable at a distance, some only up close, others only still at an angle. Considering that occasionally you need to fold, bend and see through the game information this is a difficult intersection of features to navigate.

The riddle cards that you get during play will present information in a diegetic fashion, meaning fonts may be unreadable and specific placement of information will be significant. Sometimes you need to evaluate letters or numbers in context, swap from one to the other, cross-reference the decoder wheel against environmental game state, or locate small pieces of information and link them to something else in another part of the game.

As with Unlock, the specific manifestation and intensity of these problems are going to vary from puzzle to puzzle and scenario to scenario. You won’t know in advance, absent spoilers, what accessibility issues are going to manifest. Problematically, it’s entirely possible to be faced with a problem with no indication that your lack of progress is linked to an inaccessibility. Some of the puzzles will be entirely cognitive, or require leaps of logic rather than challenges of visual parsing. However, that at best means a visually impaired player will be able to meaningfully enjoy only a portion of the game puzzles.

We don’t recommend Exit in this category, but given the lack of pixel hunting and hidden game state we maybe don’t recommend it a little less than we would Unlock. Or a little more? It’s a little bit better than Unlock – rearrange those words into whatever sentence conveys that information.

Cognitive Accessibility

The puzzles in Exit are often fiendishly clever, and they require a wide range of skills in cognitive, numerate and pattern matching capacities. The arithmetic needed may be conditional, may involve collating information from a wide variety of sources, and may involve some numbers actually being other numbers in particular contexts. We’re all familiar with the intentionally misleading equations that use non-intuitive base systems or violate the principles of basic mathematics. You’ll encounter some of those during the course of your experience with Exit.

Literacy is highly stressed and intentionally obtuse language is sometimes used – not quite to the level of a cryptic crossword (at least in the puzzles that spring instantly to my mind) but certainly beyond the construction that would yield information most directly. Some puzzles require symbolic substitution, the ability to work with anagrams, manipulating samples or subsets of words, the folding or tearing of cards to reveal new and obscured information, and more besides. The meaning of anything in Exit is malleable. We talked in the review about the concept of functional fixedness and how the destructibility of the game allows for some puzzles that would be difficult to implement otherwise. Overcoming functional fixedness though, as you might imagine, is a cognitive challenge when people are not prompted as to its existence.

Some puzzles require some general knowledge, at least in an abstract sense, as well as particular kinds of logical deduction skills. Pattern matching is hugely important in some puzzles, as is noticing anomalies in presented information. Instructions may be given without reference to where and how they are to be actioned, and later parts of the puzzle may change the context of earlier parts. You’ll often have a whole chunk of information in front of you and no clear relationship between any of it, and you won’t be able to progress until at least one puzzle is solved to reveal the information you didn’t even know was missing.

However, Exit is also very liberal with experimentation – you’re never punished for using the decoder dial. It also comes with three hints for each puzzle, one of which is the complete solution. That doesn’t make it any less cognitively inaccessible but it does offer some mitigation in circumstances where players might simply benefit from an easier experience. The scoring of the game is quite generous, and in the end if you just want to have some fun with some puzzles in an evening there’s no need to score it at all.

We can’t recommend Exit in the fluid intelligence category, but we can tentatively recommend it for those with memory impairments.

Emotional Accessibility

‘Fairness’ is an intangible thing in a puzzle because inevitably the perception of fairness depends on one’s own emotional reaction to an outcome. To my mind though Exit feels an awful lot fairer than Unlock. It feels more respectful. It feels less obnoxiously punitive in its design – it’s not looking to trip you up with your own reasonable deduction. It’s looking for you to trip yourself up and then feel clever for not doing so. That’s more than just ‘better puzzle design’ and more into the realms of a ‘better puzzle ethos’.

For some of this we come back to the issue we discussed in Unlock – that particular game had some moments where it completely undermines the basic contract it forms with the player. Exit has the same kind of puzzles but it makes a special effort to bring the player along. It builds buy-in and that’s a far less emotionally inaccessible approach.

There’s a lot less moon logic in here, and many more moments of a kind of ‘consensual appreciation’ of cleverness. Rarely do you feel like you were basically lured into taking a penalty, especially since there are no penalties of note in the game. Instead you feel given free rein to experiment. That’s exactly, in my experience, what an escape room needs to really satisfy and avoid triggering issues in this category.

The time limit in Exit is more forgiving, being based both on a top-end of two hours and primarily penalised by hints rather than failed experimentation. You’re responsible for tracking it, so you can take it as seriously or not as you like. I did find a number of the hint cards were unhelpful in the extreme and personally chose not to count them towards the score. Some of the earlier hints essentially collapse down into ‘Look closely at the card you just drew’, to which the only sensible response is ‘Yes, I’ve done that. That’s why I needed a hint!’.

In those circumstances our informal house rule is ‘if you didn’t get any new information from a hint, it doesn’t count’. That’s what a more permissive system for accounting of score permits though – there’s no app gleefully docking you minutes of your time. You decide what feels fair, what feels fun, and that’s what you’re playing against.

We’ll recommend Exit in this category.

Physical Accessibility

We’ll say much the same thing here as we did for the Unlock teardown – orientation matters, and while you won’t need magnifying glasses or such as often you will be dealing with a booklet rather than physical cards. That makes information something that has to be actively managed because you might want to look at one page while someone looks at another. Technically you could tear the booklet but you couldn’t be sure it wouldn’t make another puzzle less intuitive to solve. Exit also introduces the need for tracing of lines, viewing of cards at particular angles, and even the (relatively) neat cutting of cards to make them fit into particular puzzle solutions.

Puzzles are intensely distributed over the whole game state but more often than not only a few cards and pages will be relevant at any one time. The problem is that it may not be instantly obvious which cards and pages are going to be used for which puzzles, at least for a bit. Some scenarios in the Exit line have an explicit spatiality to go with them too, and arranging cards to support that is not only useful (as in Unlock) but actually required for solutions.

In a collaborative setting none of this need be too onerous but it’s difficult to do parallel processing of puzzles since there’s a fixed order in which these need be addressed. As such it’s not as straightforward as portioning out resources for people to manipulate in their local environment. All of the resources in the game will be in regular rotation. Some puzzles are going to need relatively fine-grained movement too as they involve close alignment of one game component with another.

That said, the game is still relatively playable – many of the puzzles involve nothing more than thinking and speaking, and where that’s not the case another player (presuming you’re not playing solo) can act on someone else’s behalf.

We’ll tentatively recommend Exit in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

The art is almost entirely environmental – there are few, if any, characters to speak of. The manual doesn’t default to masculinity, and none of the cards seem to make any gendered assumptions. That’s all good at least.

But wow, that disposable model of escape room design huh?

Here’s a true fact – I picked up Unlock before Exit because I really didn’t like the idea of having to destroy a game I bought. I only really bought the Exit games because the view of people I spoke to was that they were notably better escape rooms. And they’re right – but there was a psychological barrier I had to overcome to willingly pay £13 for a game that I was going to vandalise in the process of playing. It’s not that I wanted to keep it and play it again – it’s that I wanted to complete it and pass it on to someone else in exactly the way that Unlock permits. I understand that having these games cycle around like clothes in a spin-dryer is not a great way to ensure the sustainability of the business model. I understand that the adoption of this ‘burn after reading’ philosophy of design permits for a range of very interesting puzzles that wouldn’t otherwise be possible. That doesn’t stop it feeling exploitative. I’m often asked what these particular sections of the teardown are about – they’re about things like this. The disposable model creates a perceptual inaccessibility that almost kept me from even playing these games. The only reason I even played Exit is that several people made a special effort to convince me. If they hadn’t, I wouldn’t have bought a single one of them.

It’s more than just the money, too – the boxes are obviously recyclable but I do have concerns about the environmental impact of physical games that exist for one single playthrough. I’m not a bleeding heart in that respect, but it still feels so wasteful. I’ve got the games I’ve completed sitting on a shelf still because it’s going to take an act of psychological resilience to throw them out. That might just be me, but I’m betting it’s not. I could keep them just as physical reminders of the experience but they’re ruined – they serve no real purpose any more. I could put them together into a framed collage but then I’ve just essentially turned my hallway into a great big spoiler for Exit.

In the Unlock teardown I spoke a bit about framing – that buying a puzzle as opposed to a game puts you in a frame of mind that replayability simply isn’t really part of the equation. We expect longevity from a game. We understand a puzzle is a more limited prospect. I still hold to that, but assuming that two people play each one for two hours per scenario you’re still getting an awful lot more entertainment, at a much lower price point, than you would from an average trip to the cinema.

As with Unlock, Exit is a victim of consistency here. While the model of the escape room feels exploitative, that’s only when you view it as ‘I bought a thing and it’s mine’ rather than ‘I bought this to have an experience’. That’s a philosophical difference though. The reasons that the Arkham Horror Card Game fared so badly in this section are the same as the reasons Exit isn’t getting out alive. It’s all fine and well to discuss sustainability of business models and the real joy that comes from a perfectly pitched collaborative puzzle. If you don’t have disposable income to spare and need to maximise the entertainment from a purchase like this, Exit is an absolutely awful way to spend your money

Communication

Exit isn’t an app driven game series, and as such there are few opportunities for the puzzles to make use of sound as a key channel of information. As such, most of the communication requirements you’ll have here relate to negotiation and debate over the best way to solve the mysteries the game throws at you. That’s going to involve a fair degree of high speed discussion, although since you have a two-hour time limit the pace of discussion is not quite as frantic as it is in Unlock. The cost of trying out a solution though is negligible – just the time taken to enter it into the decoder ring. As such, while people will be interested in your train of thought they won’t need you to basically prove your theory. There’s no buzz and penalty that goes along with just giving a notion a try.

Literacy requirements are sophisticated and often require complex parsing of words in non-obvious contexts. However, since this is a collaborative game everyone is incentivised to help bring down the communicative burden. For most of what you’re dealing with it’s just jumbles of letters and numbers rather than complex text.

We’ll tentatively recommend Exit in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

I’m going to repeat what I said in the Unlock teardown – give how tentative so many of these recommendations are at best, any intersection in any category is going to invalidate any recommendation we give. There is just far too much that is intersectional in the way that the puzzles manifest and the way that they are solved. Every Exit box will have puzzles anyone can solve. There is no Exit box that has puzzles that everyone can solve.

As with Unlock, dropping out of play is handled gracefully because there are no mechanisms that explicitly scale to the number of players. The two-hour play-time of Exit is paradoxically a lot less intense than the single hour of Unlock purely because you get more time to breathe. There’s no hard-time limit either, and no harsh buzzer to indicate your failure. Instead there’s a sliding scale of score that doesn’t tick down once you hit the two-hour mark. However, there are some natural tension points built into this – the transition between scoring zones is likely to feel more stressful than the periods between them. That’s something to bear in mind – if discomfort or distress is a potential issue then Exit might be a troublesome prospect. At least if players need to take a break in the middle of the game the time management portion of the experience is entirely up to you to moderate.

Conclusion

Well, we don’t just think that Exit is a better escape room series than Unlock we also think it’s ever so slightly more accessible. This is a style of games that is unlikely to ever get our full-throated approval in any category, but there are elements in the way that the Exit series approaches this genre from which other titles should learn.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | E |

| Visual Accessibility | D+ |

| Fluid Intelligence | D- |

| Memory | C |

| Physical Accessibility | C |

| Emotional Accessibility | B |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | F |

| Communication | C+ |

Still though… this really doesn’t seem to be profitable ground in our quest to find the most accessible games in the hobbyist landscape. There are other escape room series we will undoubtedly explore in the fullness of time but I’m never going to approach one in an optimistic frame of mind.

And that’s genuinely a shame, because my time with Exit has been intensely rewarding. I can’t say that Mrs Meeple or I are particularly good at these games but we’ve certainly had a lot of fun proving our incompetence. With our four and a half stars review, it’s clear we’re fans of this particular implementation of the concept. Unfortunately, we’re not really in a position to recommend it to many of those that might have liked to have given it a go.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.