| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Concept (2013) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Light [1.38] |

| BGG Rank | 1021 [6.76] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 4-12 (3-12) |

| Designer(s) | Gaëtan Beaujannot and Alain Rivollet |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Charades, really? Are we really going to play charades? Are you seriously, genuinely, actually going to make us play charades? I mean – Charades? The game of miming things until one of us fakes a heart attack just to call a dignified end to the evening? This absolutely is not what I signed up for when you said ‘come on over for a game’s night’. What do you mean it’s not Charades? It looks like Charades. It smells like Charades. I have the fear that chills my heart whenever I’m in the vicinity of Charades. It’s Charades.

I’m on to you, charades.

Yes, I know Concept comes in a box but that’s no defence – my parents had a copy of Charades that came in a box. Yes, I know it comes with a whole pile of cards. My parents had a copy of Charades that came with a whole pile of cards. Yes, I can see it comes with a board, my parents had… wait, hang on. No they didn’t….

You might be wearing a false nose, but I can see charades hiding there.

Well, this is a new development. Okay, I will suspend my judgment. FOR NOW. Let’s see what you’ve got to offer us, little Concept box. I’m warning you though – I didn’t get balls deep in debt through reckless board-game acquisition to play Charades. Mate, you better not be Charades in disguise. Mate, you better not be. I’m warning you mate.

Use your mouth words

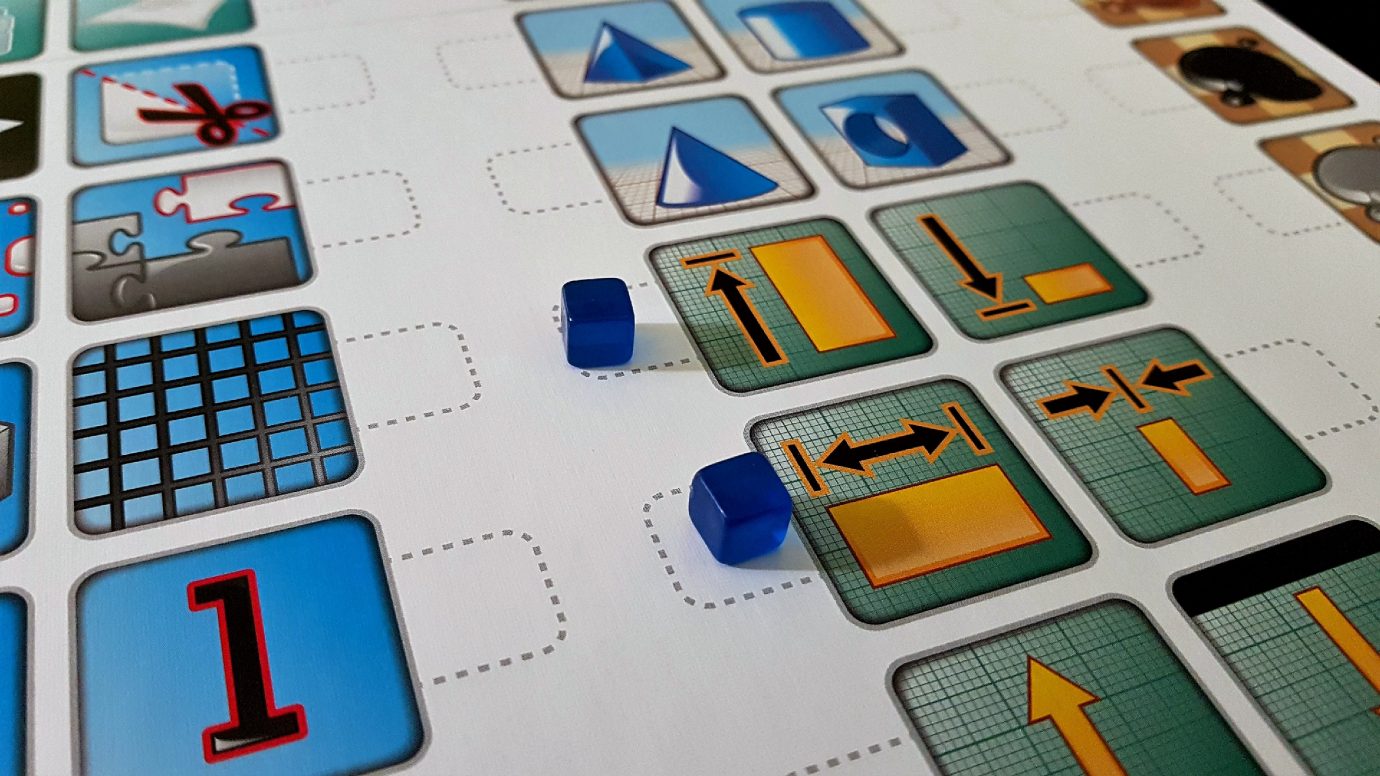

Concept is Charades – IN DISGUISE. We don’t act out mimes that illustrate the key existential elements of preposterous phrases and book titles. Not here. No – we attempt to create a chain of conceptual iconographic linkages that illustrate the key existential elements of preposterous phrases and book titles. Making use of the board, we place tokens around its various symbols to try and communicate the essence of what we just selected from a drawn card.

A generous range of choices, CHARADES.

The cards have three difficulty levels, and the level to be chosen is something you can decide upon by mutual agreement. At the easiest level you’re dealing with things like… ‘tree’ or ‘car’ or ‘fish’. At the hardest levels you’re trying to frantically represent ‘the moment of existential dread that precedes an extended bout of ennui’, or ‘the whimsical sense of loss that comes from contemplating our own mortality’. Stuff like that. You can see some examples on the cards above.

The game rules are very loosey-goosey – basically you can play it with whatever carefree abandon you like. The ‘technically correct’ way of playing it is for individuals to team up on a temporary basis, and then have everyone else around the table yell out frustratingly obtuse interpretations of your interpretative symbol-dancing. When they, largely through chance, happen upon the right answer you give them two points, and everyone on the team placing the tokens gets a point of their own. The game is remarkably casual about this though – it’s far more likely to say ‘Hey, do what you like’ as it is to say ‘these are the rules that must be obeyed AT ALL TIMES’.

You get a number of tokens with which to make your pitch, and a pile of coloured cubes to sprinkle around the board to add subtlety and nuance. Different colours allow you to express sub-concepts, and the very spatiality of the board is a tool you can use to really pinpoint the specifics of your phrases. You can place lots of different cubes on one symbol to say ‘Lots of different things like this’, or between the gaps to indicate ‘something in the middle of these’. You can pick up an especially key token and rapidly tap it against the board to indicate that ‘oh God everyone around this table is unspeakably dense’. You as a clue giver can say ‘yes’ and ‘no’ to help narrow down guesses but the only other thing you can legally do is howl in animal frustration and bite wildly until people understand.

See, the thing about games like Concept is that they thrive in the differences between mind-sets. We live in a universe where everyone around us is a fundamental mystery – their inner worlds are forever locked off from us. We are unable to ever know anything of the rich internal life of the people we see in our lives, even those we hold most dear. We can respond to this with the mute, unending horror that accompanies the true knowledge of how alone we are in a hostile, unfeeling cosmos. If that doesn’t appeal we can try something more productive – we can build our own mental models of how their mental models might be working. What Concept does is illuminate the width of the gulf between a group’s individual mental models of comprehension. That which is first and foremost in our mind shines brightly because it is where the flashlight of our attention has rested. When we illustrate our thinking it has the bright, undeniable sheen of truth. Coherence is inevitable because our neurons have stressed it must be so. For everyone else that same concept may be tidied away up in the mental attic with the spiders, or in the cognitive basement with the mice and the dead bodies.

The shadowy hinterlands between your bright understanding and everyone else’s dull incomprehension is where the fun, and the funny, is to be found in Concept. Let’s illustrate this with an example. Here’s my concept – it’s a vehicle. A land vehicle.

Car! Car? Is it a car?

And it’s a long land vehicle.

Bus! Bus! Bus!

No, it’s not a bus. Shut up, of course it’s not a bus. No, it’s also not a train. Hang on, let me help you out a bit more. It’s a long land vehicle used for work.

A work bus! A bus for going to work!

NO IT’S STILL NOT A BUS YOU ALREADY SAID THAT. Or an ambulance. It’s… an ambulance? Are you actually stupid or are you just trying to make me think you are? Fine, let’s make it even easier for Thicko McThickerson here.

A subway train! An underground train! THE LONDON UNDERGROUND??

There, now you can’t possibly get it wrong. It couldn’t possibly be more obvious. What? An underground train? You think it’s an underground train? How can that possibly be what it is? It’s a lorry! It’s obviously a lorry! The inside means you put things inside it, it can’t possibly mean anything else!

Oh, right – I’m the stupid one. Let’s see how you do PAULINE, let’s see how easy you find it. It’s not easy. You’ll make yourself look as much like a clown as I did.

Yes, a book. You let your guard down there, charades.

Yeah, fine – it’s a book. Or a work of literature. Fine. Very clever. You’ll see. You’ll see how difficult it is. What are you going to do now? Not so easy, right?

Okay, that’s pretty good.

…

…

…

It’s Fifty Shades of Grey, isn’t it?

You got lucky.

God damn you.

Right, my turn again.

Ommmmmm

Yes, it’s something to do with religion or spirituality.

The Bee Gees?

Three men, with something to do with religion or spirituality. No, it’s not John Travolta, Tom Cruise and Beck. Of course it isn’t! What possible link do they have with spirituality in any way, shape or form? You are trying to make me look stupid, I am on to you.

Oh, right

No, it’s also not Jesus, Moses and Mohammed. Uh. Let’s try a sub-concept. Three men – hold on to that thought. Now we’re adding in a head concept. BECAUSE THAT’S WHERE WISDOM IS KEPT, SHUT UP.

HEAD MEN

Fine, I’ll make it even easier for you. Philosophy and thought, IN THE HEAD.

HEAD THINKER?!

And it’s deep and wide like, oh I don’t know, LIKE WISDOM.

BIG THICK HEAD THINK MEN??

Sigmund Freud? Sigmund Freud. God, I hate you so much.

IT WAS OBVIOUSLY THREE WISE MEN

How do you know if you’re going to like Concept? Well, it depends on your reaction to the little Play in Three Parts above. Did it make you cringe? Did it make you tense? Did it make you frustrated? Maybe best avoid Concept because it thrives within these comical chasms in our shared understanding. Did it make you think ‘That could be amusing if it had been written by someone funnier’? If it did, then screw you. I didn’t make you come here, buddy. Nobody held a gun to your head and made you read this review. Why the drive by?

If it seems like you might enjoy this collaborative exercise in creative frustration, you’re almost certainly right. If you want a new, interesting spin on Charades, then this certainly fits that bill.

But…

See, we know charades. It is a known quantity. And we know that it rapidly outstays its welcome because one of two things tends to happen:

- One team is so disgustingly in sync that they effortlessly finish each other’s sandwiches, and they just dominate the evening.

- Both teams are so completely clueless that each new charade marks the beginning of a grim charnel house of frustration and recrimination.

There’s comedy to be had in watching hilarious incompetence, but there’s not a lot of water in that well. It runs dry pretty quickly. As for competent play, well… it’s boring.

‘This is a tall building associated with gears and time’

‘Big Ben!’

‘Correct. Now this is a large, white, cold rock’

‘Iceberg!’

‘Correct! Now this is…’

That can be satisfying to be a part of, but tedious to observe. To be fair, the nature of emergent dyads in the Concept rules tends to mitigate the ‘overly-in-sync pairing’ phenomenon but it doesn’t eliminate it.

Coupled to this is a difficulty curve, even within difficulty categories, that looks like a seismographic reading after an earthquake. These are all considered to be of equivalent difficulty:

- The Sphinx of Gaza

- a pen

- Atlantis

- a bucket

- beer

- the quest for fire

- bicycle built for two

I suspect I can more easily represent beer (an edible yellow recreational liquid) than the quest for fire (Uh…). Still, you get to choose one of three options for your concept so you can shy away from the ones that have no obvious starting point.

More critically, Concept seems to be a game at war with its obvious use-case. It’s a party game that supports four players and upwards. And yet most of what you do in Concept is stare mutely at the board, trying to discern its coded meaning like monkeys deciphering ancient runes. Sure there will be moments of activity and laughter and commentary about the round just played. It’s never going to be remotely comparable though to what you’ll get from something like One Night Ultimate Werewolf, Once Upon a Time, or even Cards Against Humanity.

Concept is not a bad game. With the right group it’s definitely going to be a hit. It offers a greater range of expression than Charades, exactly because it forces you to be creative within tighter constraints. Things mean what you mutually agree they mean, and part of what play will involve is creating a visual and spatial vocabulary that will allow for a precision over time that is remarkable. Everything can impart information in Concept. The order you put things down can matter, as can the precision, or otherwise, that you employ. Tokens can be used in combination with each other, or mixed together, or just treated the same way regardless of colour. You can be genuinely inventive within the restrictions of the board, and that’s certainly fun.

You can’t get away though from the fact that this is Charades: The Board Game, and while it does explore new contours of the design space in the end it sometimes feels uncomfortably derivative and displeasingly regressive. It feels a bit like a product of an older and less sophisticated place and time. While it certainly has considerable merits, it’s not really quite up to the standards that we expect of games these days. Concept is a bit like a vintage car that a collector has bought and tarted up. It’ll turn heads, inspire conversation, but still leave you longing for the power-steering of your comparatively workaday modern Volkswagen.