| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Wavelength (2019) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Light [1.11] |

| BGG Rank | 462 [7.27] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 2-12 (4-12) |

| Designer(s) | Alex Hague, Justin Vickers and Wolfgang Warsch |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

It’s a pretty great time to be a party gamer, provided that you ignore the fact that being the kind of person that brings games to a party instantly marks you out as a social deviant. The market is full of well known and well regarded titles though, and more are arriving every day. It’s out of control really. They’re everywhere. They’re on your shelves. They’re in your workplace. They’re in your car. They’re in the walls. I can hear them, scrabbling. Oh my god, they’re in the house. Get out, get out now, get out before it’s too late.

So, Wavelength.

What lies halfway between Codenames and The Mind? Actually, maybe not half-way. A scooch more towards Codenames. No, that’s too much. Put it back. God, now you’ve gone too far the other way. Let me do it, you’ll never get it. There. Now, reveal the answer.

Yep, it’s Wavelength. A game of mind-reading and team commentary that will reveal the extent to which your thinking is just utterly broken. It’s like a circuit tester for your brain – you can use it to identify where some of your neural wiring has become faulty over the years. In Wavelength you’re asked to pick a point between two extremes, and then have your team-mates guess where your opinions lie. It sounds simple. It occasionally is. Often though it’s a kind of psychotherapy of expectation, where you find out that your opinions can best be described as ‘somewhat perplexing’.

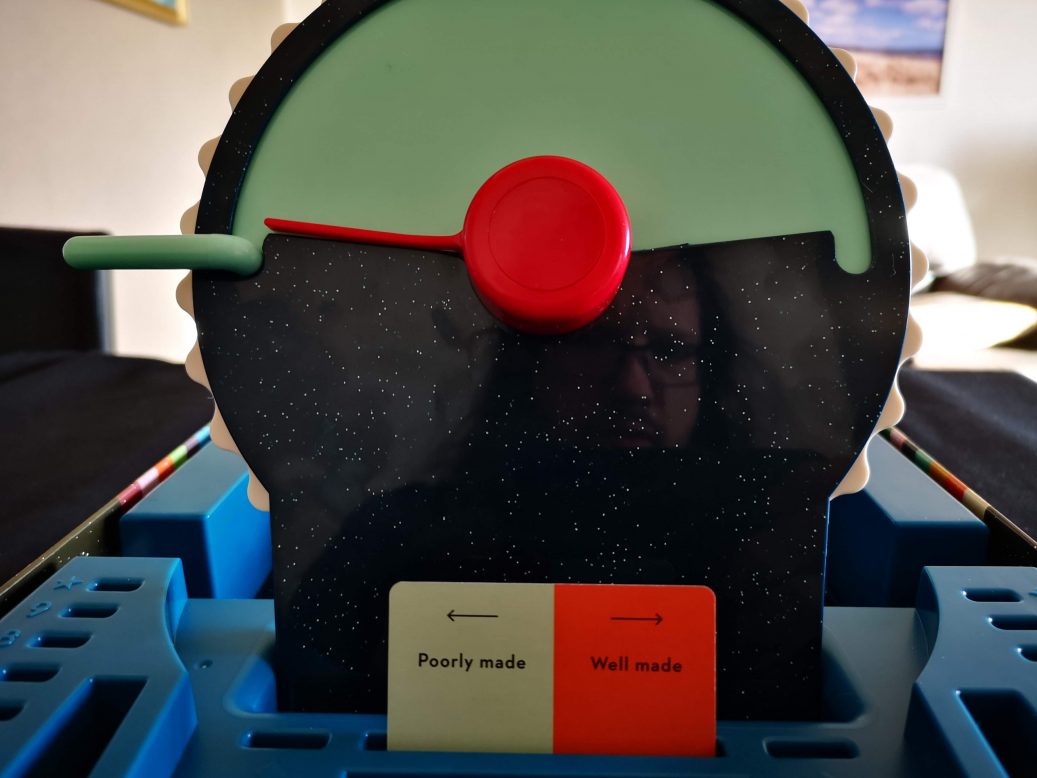

It’s a weird package of a game. A beautifully designed cover gives way to the kind of (seemingly) gimmicky plastic contraption you’d expect to see in an old-timey copy of Mousetrap or Operation. This is the guessometer. I don’t think it’s actually called that. It slots neatly into the box, because the box is the board, and has three moving parts. One is the wheel that you spin to indicate a random region in which some person, concept or object will lie. There’s a shield that you use to cover this up, and a dial that players will use to indicate where on the device the (hidden) region is. The closer your team-mates get to the right area when you give a clue, the more points they pick up.

The clues though, that’s where things get surreal.

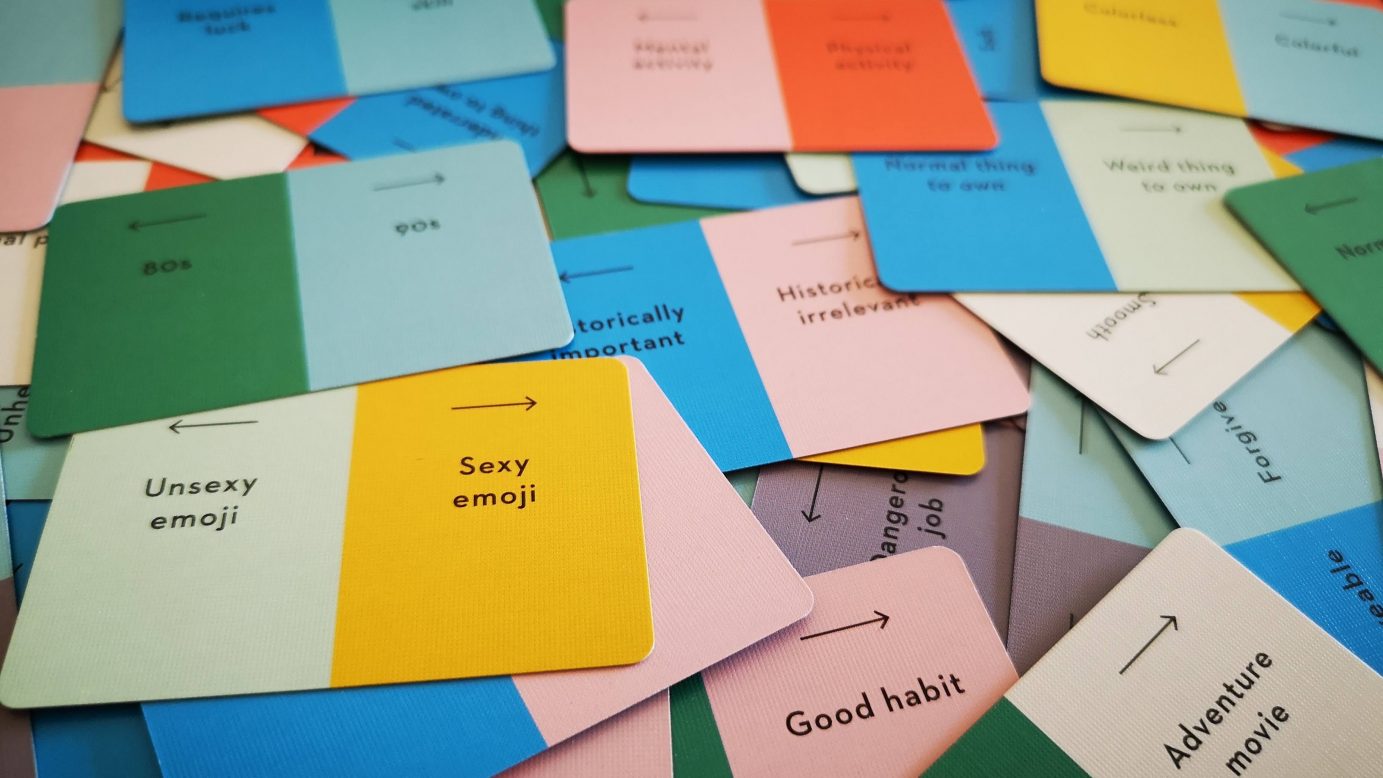

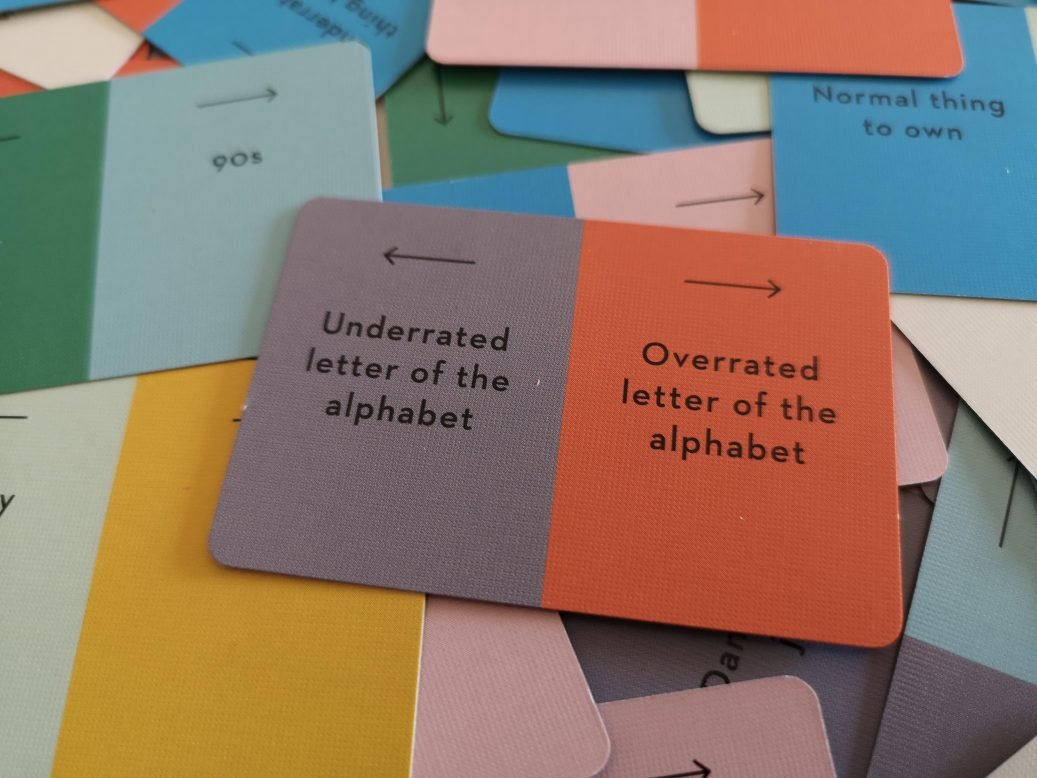

The game comes with dozens of double sided cards, each showing a spectrum from one extreme to the other. Hot versus cold. Good versus bad. Light side versus dark side. The ‘psychic’ of the team picks a card, closes the shield, spins the wheel, and then reveals the result so only they can see. And then they need to throw a metaphysical dart at a definitional dart-board in such a way that others will get the right answer. Once they’ve worked it out, they close up the shield and turn the box so everyone else can see. There are, as are typical, some rules that make it more complicated in terms of giving the clue but you can probably imagine what they are yourself.

Poorly Made versus Well Made is the spectrum you’re given. ‘The Witcher television show’, you say.

And then the team goes into a huddle.

‘I really liked it’, says one.

‘Michael only watched one epsiode’, says another, ‘So he obviously didn’t’

‘Michael is a massive bell-end though, so let’s ignore that.’

The game is called Wavelength, but it might be more appropriate to call it Convergence. From this point on, what’s happening is a sharpening of implication. You’re giving an answer, but it’s the answer you think your team-mates will think is your answer. And they in turn know that’s the flavour of the answer you’re giving. In the end your answer, and the guess, usually ends up being something nobody actually believes. You don’t aim your gun at the target, you aim it at where you think the target will be.

It’s a subtle distinction and it lends Wavelength its funniest moments.

‘Yeah okay, he didn’t like it and he knows that most of us did. But also he knows that we know he didn’t like it’

‘Wait, what?’

‘So because, as we have agreed, Michael is a massive bell-end there’s a very good chance that he’s actually trolling us.’

‘Hey, that’s right! What an asshole.’

‘He’s a hard guy to like sometimes’

‘Yeah. And let’s be honest – it’s not really worth the effort’

I should point out here that the psychic, once the clue is given, can’t say anything more.

When the team has made their guess, the other team get to say whether the real answer lies to the left or right of what was decided. Points are awarded, or not, and then play moves on to the next person. First to ten points wins.

It’s tough to guess a clue because if Wavelength draws any insight from The Mind it’s that there’s a lot of soft, subtle design that exists in the intersection of mutual uncertainty. If it draws insight from Codenames it’s that semantic incompatibility and the awareness of the same makes for interesting table talk. Even the simple reality that not everyone knows what’s going on in everyone else’s mind is a complicating factor. Cultural backgrounds make things difficult. Even simple social context puts a spin on everything. It’s a rich stew of very chunky gameplay elements. It’s nourishing. It’s hearty fare for those on the guessing side of the board.

But hoo-boy, that’s nothing compared to what it’s like to be the cook. The one that has to actually set the stew simmering.

Look, here’s a clue. What lies some unknown way between ‘Out of control’ and ‘in control’? What’s the single most out of control thing you can think of? Cancer? A nuclear explosion? A meltdown? But remember here you’re not just trying to find something with the quality of being out of control. The spectrum encompasses the set of all things. It’s not ‘Something very out of control’, it’s ‘the thing in all conception that is most out of control’. That’s where your left edge exists. And similarly for the right. What’s the most in control of all possible things?

Right, now find something that lies between those two and is approximately in the position that you saw when you opened the shield. And more than that, the one that you think the other players will guess based on the scale they imagine you’re using.

Write it out like that and it’s obvious nonsense. But you’re smart. You can work it out, right? You can extrapolate from your own knowledge and find something that applies. Except, when it comes time what you’ll often find that your brain says ‘Hey, good luck with this’ and takes a small holiday. Everyone is staring. The choice paralysis is suffocating. What even are words? What does ‘out of control’ even mean? Who even are these people, and how would they possibly know what you think about anything. We’re all alone in our heads. Maybe they don’t even exist. It’s a solipsist nightmare.

‘Woke twitter’, you blurt out.

What?

Where the hell did that come from?

I don’t know buddy but I think it came from somewhere dark inside you. Best not to worry about it. Just brick up that part of your psyche. Shhh, it’s all okay.

But you’ve said it. It’s done. Now everyone has to work out just how cancelled you’re going to be at the end of the round.

‘I think it’s very in control’, says someone as they check to see if anyone else is filming. ‘Look, I have a job I really like. I can’t take chances’

‘Lot of spoilt, self-centred shite’, says your no-nonsense, decidedly unwoke uncle. ‘Dial it all the way to the left and keep dialling until the damn thing breaks’

‘So, Michael would know that we’d all disagree’, says another, ‘So he’s going to put it in the middle’

‘But we don’t all disagree’, says another, ‘and we know what Michael thinks’

‘Please keep my name out of this review’, says the psychic in open defiance of the rules, ‘You have no idea how thin the ice I’m standing on is’

And so it goes, and so it goes, until finally.

As you’d expect, the ‘post round’ debriefing is also an enjoyable activity in itself as you try to justify your answer.

In a game we played, I was given the spectrum of ‘exotic pet’ and ‘normal pet’, and the answer was every so slightly to the exotic side. So I said ‘A dog that can say sausages’, because while it’s unusual it’s not all that unusual. Of course I had miscalibrated the scale of exoticness that others would be using. But you know, on the spectrum of ‘A normal dog that does normal things all the time’ versus ‘a wild unicorn that can melt into your thoughts’ I thought it wasn’t that bad. Esther Rantzen had made talking dogs pretty famous. In the UK. I, of course, had also neglected to take into account the fact I was in Sweden with a very international crowd, none of which – even if they had been British – would have been old enough to remember That’s Life.

In the end, this is where the game succeeds best in its design – by offering a simple proposition that is secretly a dialetic thunderdome. A violent rejection of Hegelianism and the cold comfort of rationality. A terrifying glimpse into the vast chasm between our minds and the minds of other people. It would be a horrifying game if it weren’t so funny. It’s a metaphysical nightmare presented in stand-up comedy form.

But also…

Sometimes from that perspective it’s weirdly comforting and that’s because not all extremes are as interesting to explore. Some of them relate solidly to physical phenomenon and then the only issue that really comes up is scale. Hot and cold, as an example. Well, we know absolute zero is the far end of one scale, and the other is ‘trillions of degrees’. If someone has to give something in the middle there it’s as much a question of scientific literacy as it is definitional controversy. If someone says ‘room temperature milk’ then you’re not trying to navigate a twisty maze of linguistic incompatibility. You’re trying to work out if their scale is genuinely ‘the scale of all things’ and that’s not rich bedrock upon which to build comedy.

In our recent top ten on ‘Games I’d like to Ship’ I pointed out that I would love to try this game with something more surreal, and it’s due to this issue. Some of the cards are considerably more deducible than others and it’s a weakness because a spot-on guess for cool, logical reasons is boring. Like Telestrations, this is a game that’s only genuinely fun in the unpredictable path it takes through everyone’s subconscious. It’s perverse really – if anyone actually accomplishes the task that the game sets them, the fun is dramatically lowered as a result. Skill is actively deleterious to the end effect.

You realise pretty quickly that some games require willing complicity in the fiction of their framing. Sometimes what’s needed for fun is a sold bedrock of incompetence, and there are moments in Wavelength when it feels like you need to actually fail on purpose. It’s like a hypnotist pulling you on stage and whispering ‘I’ll give you a hundred quid if you go along with everything I say’. That doesn’t ruin the act – entertainment, not hypnosis, is the goal. But still it kinda feels like a cheat.

Wavelength, despite this, is really good. Its occasional weakness is easily resolved with house rules (such as ‘draw two, pick your favourite side of the card you like the best’), and its highs are properly comic. It packs a lot of fun into an extremely compact set of rules, and finishes just before the gimmick becomes stale. It’s well worth your attention, and I think you’d be doing yourself a service by checking it out.