Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | The Quest for El Dorado (2017) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.94] |

| BGG Rank | 124 [7.69] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Reiner Knizia |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version reviewed

Introduction

The Quest for El Dorado is a light-hearted, light-weight romp through an unforgiving terrain. It’s also probably the best way I’ve seen to teach deck-building as a game mechanism to a novice audience. It’s a good game too – three and a half stars of good. Really it’s the perfect thing if you want to build the confidence of your friends so they’re happier to tackle things like Clank, Dominion or other deeper, more complex deck-builders. What better way to encourage people to try other games than showing them a simple, safe reason that they might enjoy them?

Still, that’s only going to be an option if people can actually play and that’s what we’re gathered here today to discuss. Is Quest for El Dorado accessible in every sense of the word, or is it going to get lost in the woods here? Let me grab my machete and get started.

Colour Blindness

The choice of colours of is fine in most circumstances, although as is often the case those with monochromacy or more unusual manifestations of colour blindness may have trouble. The meeples only indicate position on the board though so they can easily be replaced with something else in those circumstances.

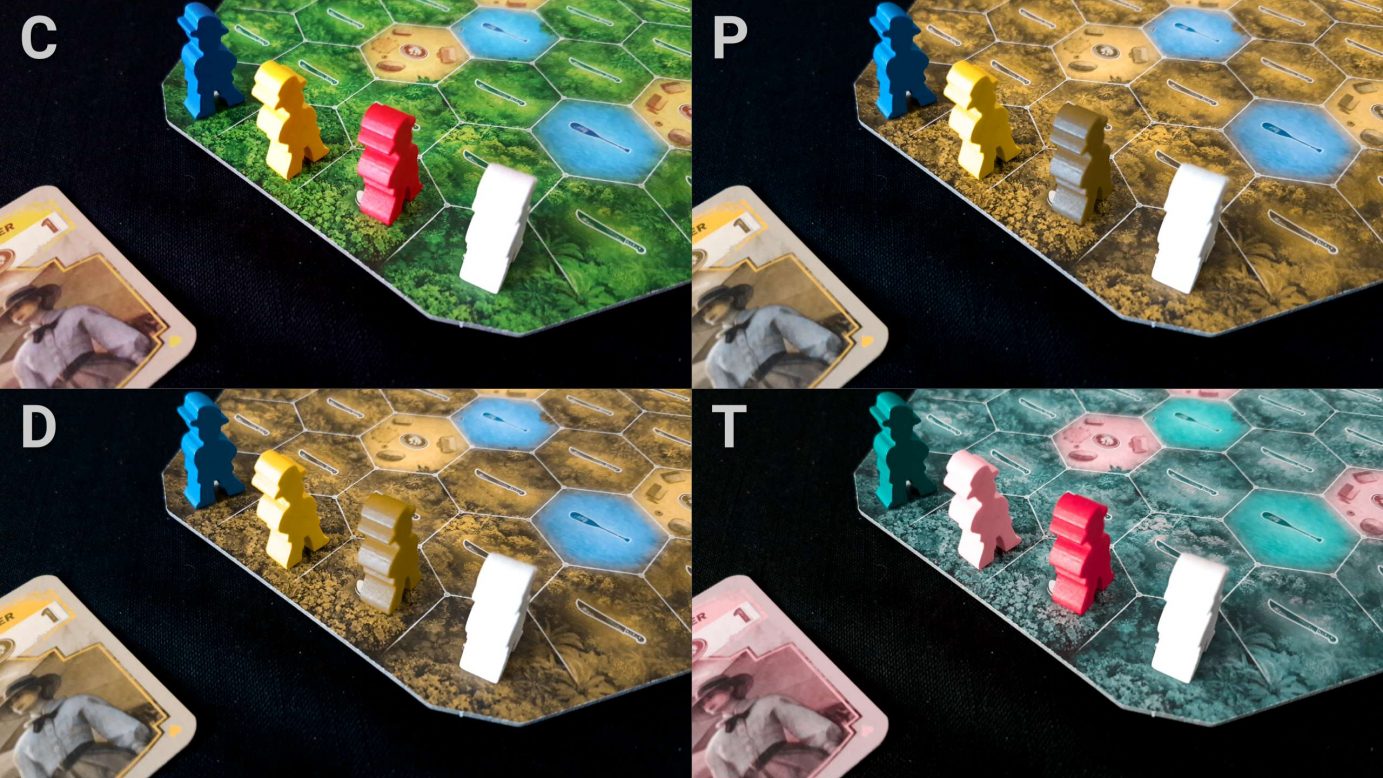

The board likewise offers few concerns for those with colour blindness because every hex is accompanied by a texture and an icon that indicates the kind of movement that satisfies its entry condition. This does become more of an issue with denser and more difficult terrain – you can see on the image below for example the difficulty in telling the green two-difficulty forest hex from the four difficulty water hex for Tritanopes. The icon disambiguiates, but also doesn’t look all that much different when viewed at a distance.

Nonetheless, there’s nothing here that is going to be a deal breaker for most conditions of colour blindness, so we’ll strongly recommend it to your attention.

Visual Accessibility

There’s a lot of information a player needs to parse, but there’s some good news in how the game handles it. Consider the image below, which shows parts of the modular board fitted together.

There is a huge amount of information on the board, but you can reliably focus on a subset. You’ll want to identify as best is possible an optimal path for the cards you are likely to draw but you don’t need to worry about what’s on board two while you’re on board one except in vague terms. The only time you need to start considering it in depth is when you’re approaching the barrier separating them. All you need to know of future hexes is how difficult the terrain is and its rough composition. You need this so as to align your card purchases with your own future requirements.

As such, the range a player must close inspect in order to play well is relatively constrained. That doesn’t mean it’s easy to do – each hex represents a step on a wider path and you’ll want that path to go where it works for you. It does though mean it’s feasible to play, for a visually impaired player, without worrying about the long term implications of where you are. You very rarely backtrack – it’s always forward and you can largely forget about the journey behind you. That’s not going to work for those with total blindness though unless they’re happy following a path someone else describes for them. There are long term implications that can be ignored, but short and medium-term issues must be considered and they are not easily described to someone.

Cards can safely be played open during a turn, and usually you’ll only have four to be concerned about unless you’ve purchased the one-off or permanent hand upgrades. In those circumstances their effect will be limited to the hands in which they appear. Verbalisation of options is straightforward – cards generally don’t have complex effects or synergy that needs to be outlined. Options, when they present them, are usually as simple as ‘take a card’ or ‘get rid of a card’. Otherwise they serve purpose primarily as markers of movement or currency.

The marketplace is open information, and the set of cards available is not small but it’s learnable. Only a subset of them will be available for purchase most of the time, and the offering is amenable to verbalisation.

We’ll recommend Quest for El Dorado in this category, although those for whom total blindness must be considered will likely want to pick a different game.

Cognitive Accessibility

Deck-builders are a cognitively complex system to parse, and Quest for El Dorado does a reasonably good job of stripping the idea back to its purest fundamentals. The largest issue that tends to arise in these kind of games is a kind of exploding synergy. Consider Star Realms for example – you draw a card which chains with another card, which means that you trigger a conditional effect which permits you to perform an action that activates a trigger which draws another card and so on and so on. It’s very difficult for some people to hold that stack of actions and triggers in mind and act upon it, and harder still to arrange the circumstances of the deck so it happens optimally.

Quest for El Dorado doesn’t have any of that. It provides the simplest toolkit for deck-building that would be needed – cards of increasing expense and power, with the ability to increase hand size and trash cards. It does introduce a somewhat unusual ‘one use’ aspect for some of the most powerful cards. Those are clearly indicated and are obvious from the fact their cost is far lower than their power would imply.

It’s about as straightforward a mechanism as we can hope for here, although it should still be stressed that there’s only so accessible that it could be given that it still involves the careful pruning of a deck to leverage efficiency and specialism.

That said, the game does have a big stress on numeracy, and in a way that can be quite counter intuitive. You can spend a three-movement card to move over three one-cost hexes. You can’t use three one-movement cards to enter into a three-cost hex. As such, the movement is not arithmetically transparent and the probabilities of movement are not necessarily easy to calculate. You might have a lot of forest movement in your deck, but if you don’t draw a card powerful enough you won’t be able to use it.

For those with memory impairments, it’s comforting to know what’s in your deck but since you get whatever cards you draw there’s nothing you can do to actually influence it. However, some cards work well in concert with others. There’s no point doubling down on cards that let you trash others if you’re happy with what your deck has, and that’s going to depend on what terrain you still have to travel. It’s not an onerous memory burden but one that will have an impact.

All this said, an accessible variant might be to simply ignore the restrictive movement rules – it would make the game much easier to play but the core of the experience would be retained. Likewise a setup that removes the most complex cards from the set of those available for purchase would mean that everyone can simply focus on speed of movement rather than deck management. A less satisfying game, but not necessarily a bad one if it’s what’s most appropriate for the group.

We’ll recommend the Quest for El Dorado in our fluid intelligence category, and more tentatively for those with memory impairments. Both of those recommendations are conditional on the caveats outlined above.

Emotional Accessibility

It’s mostly absolutely fine here. The competition is primarily over cards and efficiency. While players can block each other, it’s more unusual they can completely stop you in your tracks and it requires an very large degree of co-ordination and targeting on the part of other players.

So let me tell you a little story.

I was playing this with my mother and her fiancé. I’d been thoroughly bested in our first session, and started the second with a different philosophy. I focused on acceleration. I let them get far ahead, all the while building up momentum that I released in a great burst of movement. I charged through camps, leapt over rivers, slashed through forests. It was pretty clear that I had the deck that would let me easily reach the goal before they did even with the head start they had.

So they just… stopped in their tracks. And this is what the game was like for a good thirty minutes.

That white meeple is me. I can’t stop on the same hex as another meeple, which given the rules as they are written means I can’t move through anyone either. The only two spots available to me are occupied, and neither player was willing to budge. They sat there, cycling through cards, hoping for a combination that would ensure that they could beat me to the target. They conspired together. Eventually, tired of waiting for the random draw of cards to cycle around, I said ‘Look, pick your best cards – don’t worry about drawing them. And let’s see what happens’.

So my mother picked her four best cards, which gave her a hand that took her all the way to the river that separated El Dorado from the mainland. Fine. Then the next player neatly stepped into the position she had occupied, forcing me to take the long way around. My deck was great – easily enough to win the game if they’d each moved in their own best interests.

Still, I came second.

Now, that was all in good fun and it was funny because of how pointedly and transparently focused it was. They just wanted to stop me winning and made no secret about it. So they did just that. And it can only happen really under rare circumstances – that players conspire when they’re in one of the few locations of the board where there’s a bottleneck. It’s not likely to come up, but it’s absolutely possible for players to bully another out of being able to win. One player that decides to throw the game by holding up another will find that easy to do, and while there’s no incentive to do it the design of the game makes it very possible.

I tell you that story not to highlight a problem with the game, but rather to put it on record that I was absolutely robbed and my mother’s victory absolutely doesn’t count. It’s on the Internet. It’s official.

As I say, all in good fun and we all laughed about it – but imagine that with someone that is actually playing to win and you’ll see why this might not be a great circumstance. You can absolutely be robbed of victory, and even just non-maliciously blocked by another player doing their best.

Score disparities don’t really exist, and in my experience players will tend to all be in a competitive position when it comes to the last stretch of the race. However, it’s certainly possible for someone to lose while everyone else wins. If you don’t make it to El Dorado, you’re not even in the running. For players that reach it on the same turn, the number of temporary barriers they broke down on the way is the tie breaker. There is an odd circumstance there in that someone can basically make it an easier journey for everyone else but lose out if they don’t actually reach the goal.

All of these issues are unlikely though, so we’ll still recommend the game in this category.

Physical Accessibility

There’s a lot of shuffling in the Quest for El Dorado and with maliciously small cards. It’s a really bad combination – something that’s going to be frustrating and annoying for everyone. I really wish they’d gone with full sized cards, although that would have required more consideration of how the marketplace works. The playability of the game does suffer here though.

Reaching over to move a meeple often involves a fair amount of stretching depending on the map, and this may require assistance from the table especially as the meeples get farther and farther away.

However, the deck of cards players build up will be relatively small and it’s entirely possible for someone to play with verbalisation only. All they need indicate is a card to spend and an effect its’ to have in the game. The mechanisms of the deck building itself will handle the rest.

The board is something of an issue, being made up as it is of modular parts separated by thin and awkward barriers that get removed when someone passes through them. This requires the rest of the board to be nudged back into a solid whole. The modules don’t snap together like they do in something like Flamme Rouge. They just push up against each other. They can also take up an awful lot of space on a table. Nudging a surface will upset the map but it’s not difficult to neaten it up again in most scenarios. The hexes that can accommodate meeples are reasonably generously proportioned and only one meeple will ever be in a space at any one time.

We’ll recommend, just, the Quest for Eldorado in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

Once again you’re playing the role of explorers, almost explicitly cast as from the technologically advanced imperial powers that plundered the world in the 18th and 19th centuries. You’re all looking to find a South American city with the intention of looting the bejeezus out of it. There’s no projection there – your motivation is right in the manual. You’re not archaeologists. You’re thieves. That remains to my mind a problematic framing. It helps a bit that El Dorado was almost certainly a mythical location, but the intention of strip-mining a culture for its resources is an all too real aspect of the semi-recent past.

At least an effort has been made in the cards to make looting into a somewhat diverse profession. Many of the cards (Journalist, Adventurer, Millionaire, Scientist and more) show Lara Croft-esque women adventurers. The rest show men, including a couple (such as the native and the scout) that have an expressed ethnicity. That in itself might be viewed in a negative frame by some people given it’s vaguely fetishistic in how it’s done. The box gives prominence to a Mesoamerican golden mask, but the characters that can be most clearly seen are men. You can see the millionaire heiress in the back of a canoe but you need to know what you’re looking at. It’s a mixed bag.

The Quest for El Dorado has a an RP of £30, and supports between two and four players. As discussed in the review it’s an excellently approachable way to introduce a complex game mechanism to a novice audience. That means it’s a good fit for any game night where you don’t want to have to explain the finer points of deck curation to an indifferent audience. There’s not much distance between opening the box and having fun, and that’s an important trait for a game like this.

We’ll recommend the Quest for El Dorado in this category.

Communication

There’s no need for communication during play, although literacy is required to interpret some of the card effects. At least initially – it’ll get easier the more the game is played because their powers aren’t particularly complex.

We recommend the Quest for Eldorado in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

Close inspection of the board will become more necessary if someone has colour blindness and a visual impairment – colour may not be a reliable indicator of terrain to come, and the icons likely won’t be distinctive enough to compensate. Physical accessibility issues may compound this, making close inspection difficult.

The size of the board too is likely to be an intersectional issue, particularly if visual impairments and physical impairments intersect. You don’t need to worry too much about distant territory but it’s a good idea to be adjusting your deck in line with what terrain is most common ahead. Getting up close and checking the difficulty of the hexes may be difficult in this circumstance.

The Quest for El Dorado can take a surprising amount of time, depending on the specific board configuration. Pauses in the action are common as people are unable to make progress. I’d estimate at least twenty minutes per player, barring accessibility compensations. A four-player game is likely to take well over an hour, although smaller maps can be built if that’s likely to be an issue. There’s a good deal of flexibility there although it’s not straightforward to balance smaller maps against game balance. There’s a solid community of suggestions though that can be drawn from and the box contains some outlines of configurations of varying difficulty – the easier the map the quicker it will be.

The game does permit people to drop out of play – nobody is dependant on anyone else. You can leave them where they are, or simply execute upon their cards like a robot player. However, moving from three to two players is more awkward since at that count each player should be given two adventurers and that’s not something that can be retrofitted into an ongoing game.

Conclusion

Well, this turns out to be an accessible game in a lot of categories, doing good work to bring the concept of deck building to the widest possible audience. It is, as always, not a flawless performance. Just a strong one.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | A |

| Visual Accessibility | B |

| Fluid Intelligence | B- |

| Memory | C |

| Physical Accessibility | B- |

| Emotional Accessibility | B |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | B |

| Communication | B |

I have often argued that Spiel des Jahres nominees, of which this is one, have a moral duty to exemplify good accessibility practice. It’s not always true, and I’ve been rebuffed in the past when trying to get the SdJ judges to adopt accessibility as a formal deliverable. I’m pleased to see that the Quest for El Dorado is a game that I can hold up and say ‘Look, it can be done’.

We gave the Quest for El Dorado three and a half stars in our review. A good, fun game with a lot of heart. Approachable in a way that other, heavier and more complex games couldn’t hope to be. Enjoyable for novices and those that have already mastered the intricacies of Dominion, Clank and the other deck builders. If you think it sounds like your cup of Yerba Mate, there’s a fair chance you could pick it up and play it with everyone you know.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.