Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Tash-Kalar: Arena of Legends (2013) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.84] |

| BGG Rank | 774 [7.16] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Vlaada Chvátil |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

A review copy of Tash-Kalar was provided by Czech Games Edition in exchange for a fair and honest review.

Version Reviewed

Introduction

Tash-Kalar is a very fine game and I don’t want to play it. This isn’t like Catan where I begrudge every second it’s in front of me, or even Magic Maze where I think there’s something fundamentally appreciative of joy that’s broken inside me. It’s just Tash-Kalar asks too much of everyone that sits down to play it and if the balance is off the whole thing starts dangerously grinding like a misaligned rod in a car engine. You can read more about that in our review though – you’re here for meatier fare than our opinion. You want to know if you were in the arena with this behemoth whether you’d be in a position to meet its challenges. Let’s find out.

Colour Blindness

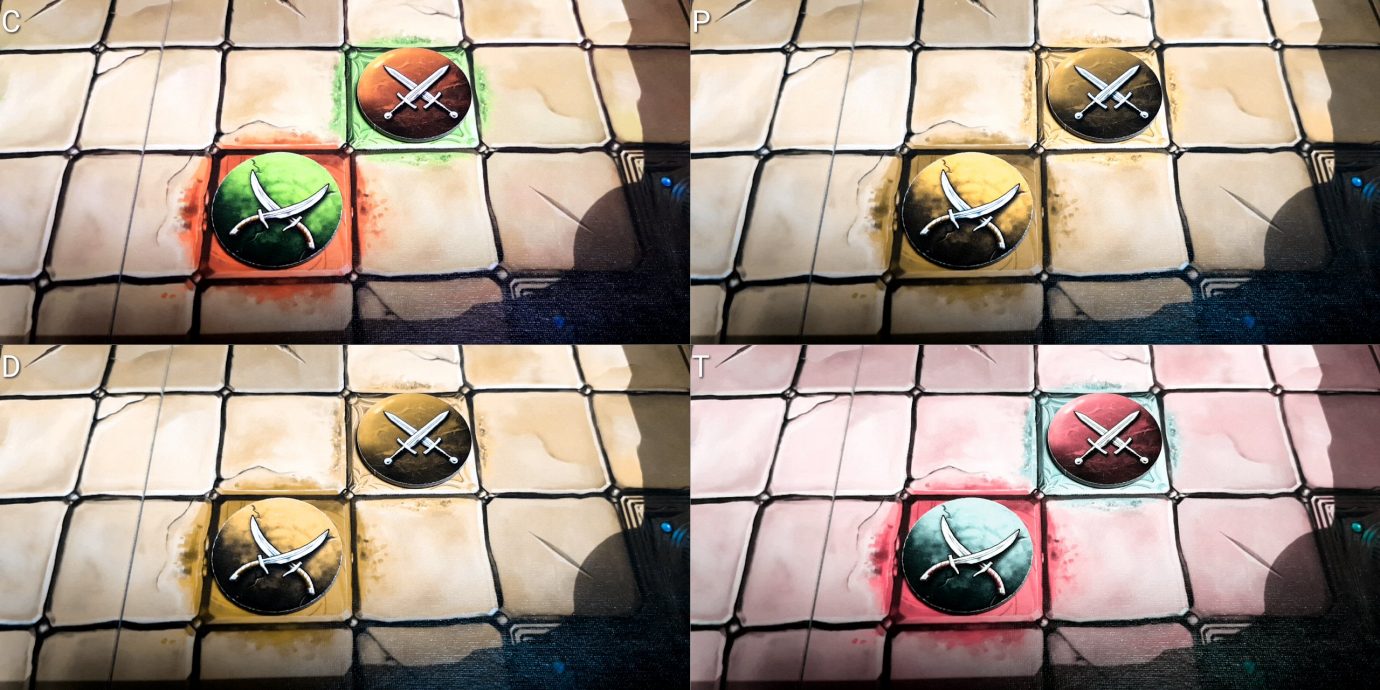

Well, it’s not ideal. The board is mostly unadorned except for red and green patches that indicate squares of special power and significance. Those are a problem for those with Protanopia or Deuteranopia. Now, that’s a statement that needs some qualification because they actually have different swirl patterns and as such technically they are accessible.

Over time players will come to internalise which squares are red and which are green – their presence on the board is fixed. However, these are spots that tend to see a lot of competition because they’re used in several scoring conditions and summon powers. When they’re occupied, they’re much harder to make out and they’re more likely on average to be occupied than other squares.

The cards that represent colour-specific scoring opportunities are labelled with the colour, but that doesn’t necessarily help when comparing the cards to the board and vice versa.

This is a game too where inquiring of the colours is almost certainly going to give away some gameplay information and in Tash-Kalar that is hugely problematic. If someone suspects you’re trying to claim a coloured square they can deduce, with sufficiently familiarity of the game decks, what you might be up to. Sure, you can use that as a bluff but that opens up its own problems.

The colour issues extends to the pieces to an extent, but each different faction has its own subtly different icon to help alleviate colour identification problems. That is except for the two imperial armies but their opposing colours are red and blue. While this can be a problematic choice it isn’t in the majority of circumstances. In any case there’s no problem with a player using the tokens of an unused faction if it becomes a barrier.

Interestingly, the full rules references provided for Tash-Kalar adds its own inaccessibility by colour coding the instructions for the different game modes:

It’s the very definition of an unnecessary own-goal.

All of this said the problems aren’t insurmountable and familiarity with the board and the rules is going to make them easier to deal with. The problem really only comes in when a square is covered by another piece. We’ll recommend Tash-Kalar in this category, just, but it’s a substandard performance that is saved from a worse grade simply by the decreasing impact it will have over time.

Visual Accessibility

So much of Tash-Kalar is an act of spatial processing that I think it’s probably effectively unplayable when considered with regards to this category. Everything you do is a pattern matching exercise and that exercise is hard enough if complete visual information is available. Certain parts of the game have a degree of tactile accessibility (legendary tokens versus standard/elite tokens) but it’s not enough to make this game a promising candidate for a recommendation here. The vast majority of the game information is presented only visually.

To summon a creature you need to match a pattern to the board, and for legendary creatures that may include a mix of elite and common units. The rules permit you to rotate patterns or flip them (in any combination) to make a match. That can be difficult enough even when you can make out a precise pattern on a card because you have to cross-reference it to a densely knotted mix of units on the board. Some cards come with secondary effects too that need to be assessed in light of the distribution of pieces. You may for example destroy pieces when you summon another or trigger an effect that only works under certain circumstances. You also need to be making your decisions with reference to what an opponent might be trying to do with their own patterns.

Coupled to this is that cards are intensely information dense because of the way patterns work, and often poorly contrasted with highlighted squares being white against a grey interior, or yellowed against a grey interior. The specifics of these highlights may be deducible by patterns but they are also often completely unique with no obvious hook to lend tractability to their placement. The contrast on the descriptive text is good, but the font is sometimes unreadably ornamented and in any case is often complex and specific in its effects.

Consider here two specific examples – the centaur chieftain which has tremendously low contrast on the square where it appears, and the Kiskin Leafsplitter which has arrows to indicate an area of effect when summoned. The placements of the grids are not consistent, their sizes will change according to the patterns, and the background art, while lovely, also tends to obscure key details because the patterns are slightly transparent.

Those with minor visual impairments may have a happier time playing Tash-Kalar as primarily it depends on the extent to which examining a handful of six cards (only five of these contain patterns to assess) against a board-state that is rapidly changing and evolving. Close inspection of both is possible but there’s a combinatorial effect that comes with assessing five complex patterns against an equally complex board state and then doing the same for each combination of rotation and flipping just to see if it’s valid. Working out whether it’s a good move is a whole additional complexity on top of that.

We don’t at all recommend Tash-Kalar in this category.

Cognitive Accessibility

Here be monsters. Great, big, massive monsters. Monsters that will kill you as soon as look at you. There is almost no good news here for either of our categories of cognitive accessibility.

First of all, there’s a reading level associated and it’s high. The conditions on each card are specific and while they are expressed clearly their logical impact is sometimes difficult to fully parse because of how contextual they are. Even whether or not you can summon something depends on a comparison of the type of creature it is versus the square it’s on. There are important differences between a combat move, a standard move, and a leap. There are a lot of rules in Tash-Kalar and their effective interplay is key to making sure it works. This is a well-balanced, well designed game but that comes with a fragility. Misinterpretation of rules can break all of that.

The spatial intelligence required to play patterns is substantial. I’m pretty good at mentally manipulating shapes and patterns in two dimensions, but I found this incredibly difficult to play at times. The additional freedom offered by permitting rotations and flips just adds a huge mental burden to play to work out if a move is valid. It often comes with a degree of verification from the table as you explain to people why your move is valid. If a game requires a corroboratory audit after every move you know it’s not likely to do well in a category like this.

The game state becomes very complex and it changes rapidly on a turn by turn basis. What seems like a dominant advantage for one player can be swept away in one good turn. That’s possible because the game also permits intensely powerful synergies of chained positioning. The role of a summoned creature might be to permit the pattern that would allow a legendary to be brought into existence as a followup action. That kind of thing needs a deep understanding of how all your cards fit together. To a certain extent the cards you have available are all ultra-situational but you get opportunities to bring those situations about. Effective play in Tash-Kalar is built on this. If you can’t work the card combinations you’ll find it very difficult to accomplish anything because of how chaotic the board-state is once your turn is over. You have to find ways to control the game inbetween the start and end of your turn if you want to make anything happen reliably.

Game flow is mostly consistent in its structure but wildly flexible in what that actually means. A turn in Tash-Kalar might involve placing a piece or it might involve summoning a creature that wipes half off the pieces away before permitting everything else to move. Turns, in other words, can bear very little similarity to each other.

It’s a game too that doesn’t really permit meaningful play with differing levels of cognitive ability because a skilful player will absolutely destroy a less skilful player, and it’s no fun to be on either end of that exchange. There is a team mode, but it’s ‘team versus team’ rather than ‘team versus the world’. It permits some collaborative play but not enough for it to be a suitable fallback for a recommendation.

The numeracy level required is not high but you need a good understanding of the game systems to understand the value of points. Two points you can reliably get next turn are worth many more than the four points you could get the turn after because viability has a half-life here. It’s not that the arithmetic is difficult but rather the calculation of value versus attainability. There is a simpler deathmatch mode that alleviates this somewhat but in the process it also dials up the competition several notches to the point it actually makes things worse overall.

When placing pieces you are often not doing so for the current turn, but rather for the turn you hope you can have if nobody undermines your patterns. As such, there’s an intense decoupling of outcome from action if you can’t harness card synergies to accomplish your goals.

For those with memory impairments, all of these come into play but there’s an additional complication – knowing how to play Tash-Kalar well depends on understanding your deck and ideally the deck of your opponent. You need to know what you can do and what they can do and what you can do to undermine what they can do. As is the case with Twilight Struggle, if you don’t memorise the deck compositions at least to a certain extent you’ll find it incredibly difficult to compete. Playing the wrong card at the wrong time can very much set you up for a riposte that puts you out of contention.

We don’t recommend Tash-Kalar in either of our categories of cognitive accessibility.

Emotional Accessibility

The competition in Tash-Kalar is pointedly aggressive, and a satisfying flow of the game depends on a rough equity of ability. If that’s missing it can become profoundly unpleasant to play. You end up listlessly tossing out useless units you know are only going to be completely destroyed before you get an opportunity to summon some more useless cannon-fodder. It can certainly be frustrating, but frustration tends to imply being prevented from achieving a goal. Often in Tash-Kalar you know your situation can’t be changed and as such it mostly becomes a kind of resigned hopelessness.

Abstract games sometimes evoke the intellectualism of chess, and there’s often a perception that comes along with this that good players are smarter than bad players. It’s not necessarily true but it’s an impression that society tends to reinforce through all kinds of cultural touchstones. Tash-Kalar can make you feel very dumb, especially because mistakes can’t be fixed – you lose the card, and your piece is glued to the board until you can trigger it in some other way.

To an extent that feeling of being stupid is a simple side-effect of a game that puts so much pressure on a player’s ability to wield its game systems like weapons. Tash-Kalar is never unfair, but fairness often feels unfair – a point that we made when we spoke about Catan. This is a game that is completely fair, but also deeply unkind on occasion.

The focus on patterns too can be upsetting for some players with compulsive traits. The whole game is about preventing people forming patterns while you form your own. that means inevitably that more often than not the goal that you’re working towards will be smashed before you get to see it through. The entirety of Tash-Kalar’s design is one big ‘take that’ moment where the largest amount of joy comes in from the greatest amount of damage you inflict on an opponent’s complacency. While there are few reasons for players to gang up on another, the game also ensures it’s going to happen as a natural byproduct of play.

The result of all of this is that score differentials tend to be very high, and that while nobody is ever eliminated from the game there comes a point where someone can basically have no more fun because everything they do gets completely undone by the next player. The flare cards can help with that, but they don’t solve the problem.

We don’t recommend Tash-Kalar in this category.

Physical Accessibility

Mmm, this is also a problematic category but primarily for those who must play with verbalisation. It’s not ideal for others, but the tokens are quite large and while the squares are not spacious the game is also reasonably resistant to careless nudging. You occasionally need to reach in to a mass of tokens to flip or remove one, but other than that the game asks little of its players on a physical level. The business of the board is the primary issue.

You have a hand of cards, but while the churn is quite high you only ever have six of them. The problem there though is that you need to see the full card each time to get the complete swathe of its impact. You need its descriptive text, its pattern, and its classification. As such, a card-holder is feasible but you might want two. The good news there is that your card churn is actually differential – your regular cards will be used more often than your legendaries and your flares, so you can offload them into a secondary card holder and focus most of your effort on your first.

The biggest problem though is that it’s a game where fine positioning of pieces is important but the board offers no grid references.

You can get around this by using the hot spots as a kind of landmark, but sometimes you’ll be in the position of having to explain a rotation, an area of impact, a mirror image and a card to someone based on the presence of tightly knotted units.

Let’s say here you were trying to indicate one of the units around the red spot so you could summon a creature. There are three standard units by red spots as well as an elite unit. You’d have to disambiguate which spot as well as which unit. Then you’d need to say which card you wished to play and which rotation, and then you’d need to explain how that orientation relatedsto the piece you earlier indicated. Is that piece supposed to be the centre? The top? Something else? You could come up with a vocabulary to explain that but it’s likely to be situational based on what actually provides the clarity you need. It’s not impossible, but it’s much harder than it should be when grid references would have made it much easier. It could be a simple as saying ‘Play my third card, centred on square D4 so that it destroys the unit at E8’. And yeah, you can make your own grid references but I much prefer those to be baked into the game in some way.

We’ll very tentatively recommend Tash-Kalar in this category. It’s playable but the verbalisation and physical manipulation is less convenient than we’d like to see.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

The manual doesn’t default to masculinity, but there’s a lot of flesh on show. To be fair, it’s mostly the heavily muscled Conan type men in the Highlands deck that have their tits out. The Sylvan deck though does have a few somewhat eroticised cards.

Whether this is going to be a problem depends on your frame of mind I think. Beth Sobel over on Twitter (sorry, I lost the link) said that the appropriateness of sexuality in art depends on what it does for characterisation. If it leads to a deeper, more interesting character then it’s being employed in the right way. If it just leads to ‘This is a sexy woman, look how sexy she is’ then it’s being employed inelegantly. For the Sylvan characters I think you could make a strong argument that the nature focus is inextricably bound up in the characters presented. Similarly for the Highland school. The women characters for the imperial faction are more comfortably attired which would tend to suggest the flesh on display is characterization rather than titillation. As ever though the final judgement lies with you.

Cost wise, it RRPs at around £27 and given the depth and complexity of the game it’s hard to fault it at that price. You will, if you are willing to learn its intricacies, absolutely get your money’s worth out of it.

We’ll recommend Tash-Kalar in this category.

Communication

The reading level associated with play is high, and the sophistication of the language used is complex – not in terms of vocabulary but in terms of the expected precision of interpretation. For example, ‘If the Ritual Keeper was summoned on a green square, upgrade one of your common pieces; if on a red square you may do 1 combat move with 1 of your pieces’. There’s a lot to unpack in there and getting it wrong has a considerable impact on play. For the Forest Wardens, ‘Destroy 1 common piece of an opponent with more common pieces than you. Destroy 1 heroic piece of an opponent with more upgraded pieces than you’. This kind of linguistic construct has to be evaluated in secret from a hidden hand and assessed against a complex and ever-changing game state. If language problems are at all an issue this is likely to be a deal breaker.

Otherwise, there’s no need for communication during play.

We’ll tentatively recommend Tash-Kalar in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

There are only two intersectional issues that really emerge because of the low grades across the board. The first is that close inspection of the board may be necessary for those with colour blindness and if this compounds with a physical impairment that prohibits this it would invalidate our tentative recommendation. It’s similarly true with communication impairments that intersect with physical impairments. The amount of nuanced communication required to precisely articulate intention is significant and if there is a difficulty there we’d recommend players avoid the game.

Tash-Kalar cites a 30-minute play time but I think that must be with the assumption there’s virtually no thinking time. I think it’s much closer to 30 minutes per player – for a two-player game that’s still reasonably nippy. The more players you have the more chance you’re going to find yourself in a position where it gets long enough to exacerbate issues of discomfort or distress. It’s not at all easy for players to drop out of play either, because their pieces play a vital role in setting up the competition space of the game. You need them to be moving and evolving to make space for other pieces, and you can’t simply leave them there. However, you also can’t remove them without dramatically altering the game state perhaps to the intense advantage of another player. Realistically this isn’t a game that supports someone dropping out without someone else tapping in for them.

Conclusion

Challenging, complicated and deeply thinky. Tash-Kalar has a number of fixable problems but as is often the case it’s just that this kind of game leads to some deeply inaccessible elements. A game that is all about spatial manipulation, unit positioning, card synergy and the weaponization of momentum is never going to be a strong candidate for a high grade in many of these categories. It could have done better but it’s unlikely it would have ended up with a meaningfully stronger profile.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | B- |

| Visual Accessibility | E |

| Fluid Intelligence | E |

| Memory | E |

| Physical Accessibility | C- |

| Emotional Accessibility | D |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | B |

| Communication | C |

Primarily here though the cognitive costs are unavoidable and the spatial interpretation is what lends Tash-Kalar its deep, intense gameplay. A better colour choice, grid references on the map, greater support for collaborative play – all of that could have helped but in the end there’s only so far any of it can go.

We like Tash-Kalar a lot – from a distance. The biggest issue we have with it is that it asks more commitment than we’re prepared to give. I have shelves and shelves full of games that aren’t getting enough attention and Tash-Kalar ultimately isn’t quite interesting enough to wrap me up into its cardboard arms. There’s no doubt though there’s a game in here that you could devote yourself to if you were willing to make more of an effort than I am. Unfortunately, that game is also intensely inaccessible so perhaps you might be better served in any case looking elsewhere for your fun.

A review copy of Tash-Kalar was provided by Czech Games Edition in exchange for a fair and honest review.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.