Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Scotland Yard (1983) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.95] |

| BGG Rank | 1574 [6.50] |

| Player Count | 2-6 |

| Designer(s) | Manfred Burggraf, Dorothy Garrels, Wolf Hoermann, Fritz Ifland, Werner Scheerer and Werner Schlegel |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Ravensburger English edition 2014

Introduction

Scotland Yard is a game that was remarkable at the time – clever, creative and the first game of which I can think where the formula of a hidden movement game was fully expressed. It doesn’t stand up quite so well today, but there’s only so much you can expect after twenty-five years. Its legacy is strong, but it has been eclipsed by many of its younger descendants. We gave it three stars in our review, which is still a respectable score. Those that find heavier fare like Fury of Dracula too complex may still find themselves well served by Scotland Yard.

One of the things we have found in our exploration of older games is that the passage of time and their equivalent passage into mainstream attention tends to result in accessibility innovations across the board (teehee). Is that going to be true of Scotland Yard? Let’s find out.

Colour Blindness

Unfortunately we don’t start off particularly well.

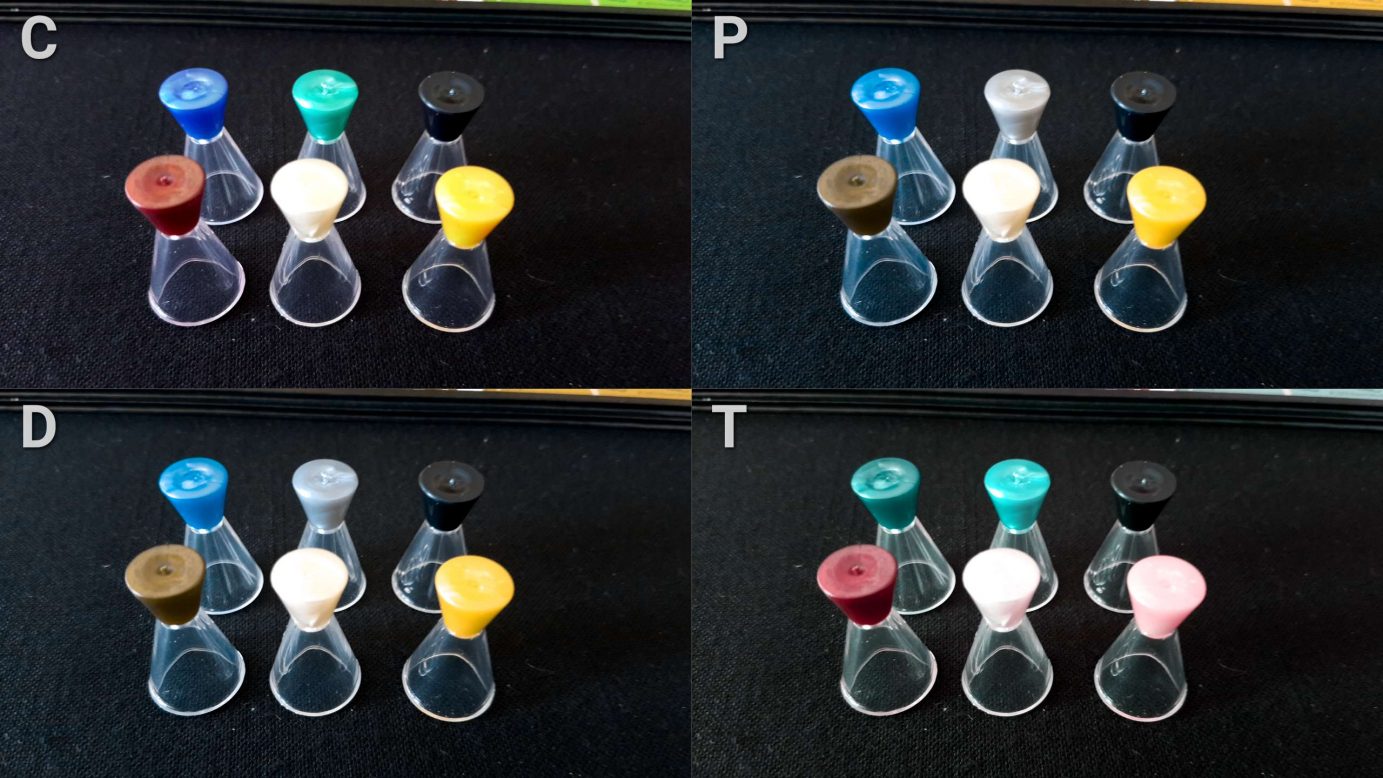

The palette chosen for the detective colours isn’t the worst thing we’ve ever seen but it is likely to be something of an issue for some players.

Close inspection will almost always reveal which detective is which, but part of the job of a smart Mr X is to observe who is where and what tickets they have available. If Mr X thinks that the blue detective is actually the green detective, that’s going to become an issue. Worse, asking players or looking too closely has a risk of revealing unintended information, as does a pantomime of misdirection. This is only going to be a big issue in full player count games, but something to bear in mind. At lower player counts, a degree of disambiguiation is provided by the collars that distinguish bobbies from detectives.

The board is colour blind accessible – locations with a station have a different coloured number (white instead of black) and a different coloured background. Bus stops are indicated by a semicircle on the location. Close inspection may be needed here in some cases of severe colour blindness (particularly monochromacy) but there is no information that cannot be drawn from the map itself. Everyone is going to need to peer at the board at times, so colour blindness isn’t necessarily a large problem here.

Tickets and player boards are annotated with icons, and there is otherwise no colour information used in the game.

We’ll recommend Scotland Yard here, just with a minus. It’s playable, but larger player counts are going to have an impact on that playability. All the pawns do though is indicate position and alternative pieces can be used.

Visual Accessibility

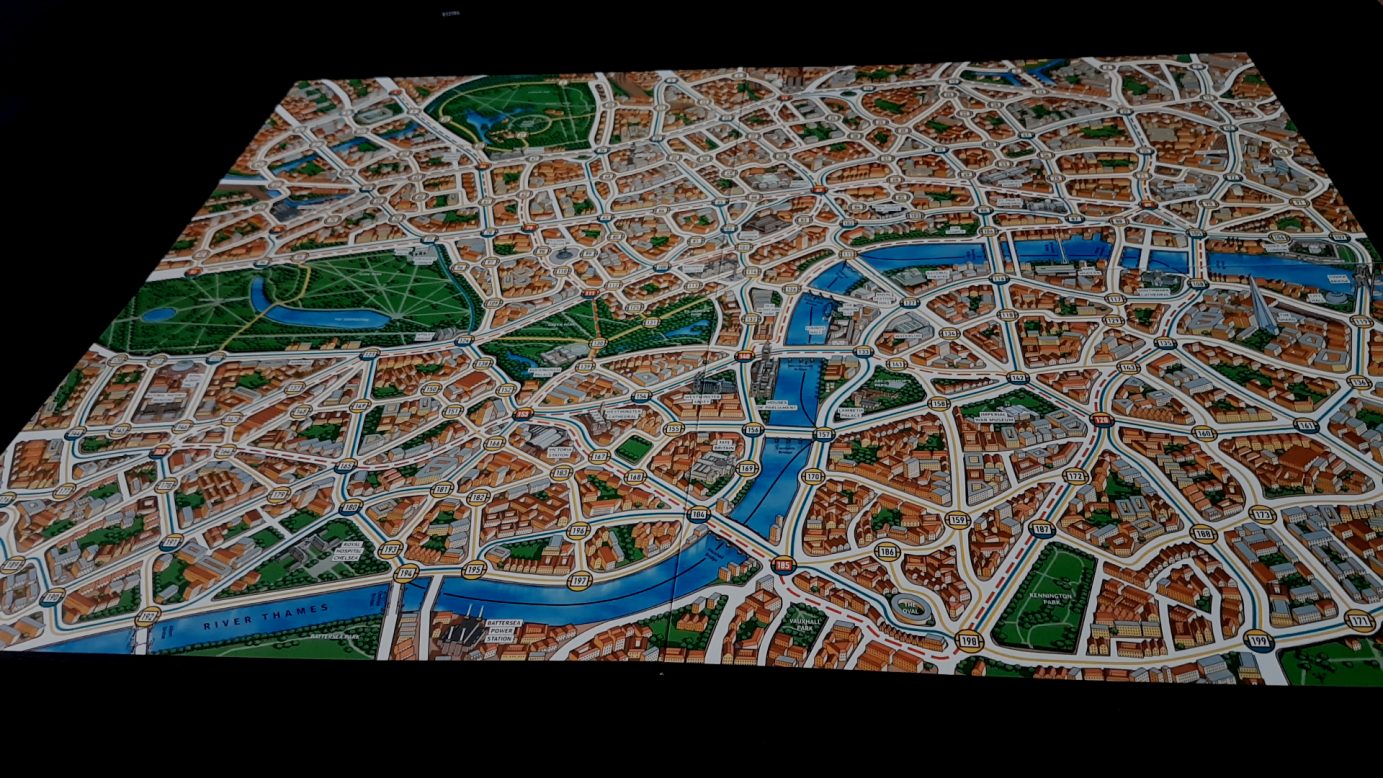

Oof, forget about it. This may be the least visually accessible turn-based game we’ve examined on the blog. We’re dealing with a large board that is staggeringly dense with information, and with hundreds of individual locations that have distinctive travel profiles. Look at the thing in its entirety.

Now look at it close up:

Notice each location has a profile that tells what tickets are valid, but also what routes are available. You can’t take a bus from 122 to 94 – there’s no connecting line. You can’t take an underground from 93 to 74 – again, there is no line. The linking up of each of these nodes occurs in complex ways and to hold them in memory puts a phenomenal burden on a player.

Often in these circumstances we’ll suggest close inspection as a possibility, and that’s definitely something that can be done here. Physical pawns are used to indicate current position for everyone except Mr X. Unfortunately this doesn’t really work here because of information leakage. Close inspection will be necessary of every player but sighted players will be able to get away with more deception. If I’m Mr X and I’m at position 124, the last thing I want to do is pay too much attention to that location. I want to look over at the other side of the board. Ponder locations far away. Look at locations that are plausible but not accurate. Let my eyes drift over 124 and then elsewhere. I need to get this information in snippets if I’m not going to reveal too much to the table. A player with some sight will be able to do this but it’s all so much more difficult, cumbersome and difficult to pantomime if one has a visual impairment. Even the way in which things are pantomimed will be revealing. A blind player can’t simply sweep their eyes across the board and expect it convince anyone.

That’s an issue particularly for Mr X who must hide intention and also provide the audit trail of written movements, but it’s also important for detectives so as to mislead Mr X as to where they might be investigating next. If I want you to think it’s safe to head across Hyde Park, I’m going to make sure I look most intently towards Picadilly Circus.

The numbered locations are mostly in order from left to right, but that makes individual nodes difficult to find. There’s a lot of poring over the board to find specific locations, such as during set up. Proximity is not what defines the numbers, and the left to right numbering isn’t always obvious. Consider the image above – 166 connects to 183 which connects to 167. 168 connect to 184. Edges are particularly problematic for this. When starting the game you seed detectives and Mr X around set locations. Finding them can be awkward and will be more so with visual impairments. The player with Mr X, again, has the most difficult task because for someone to help they need to be given compromising data.

The tickets at least are very visually distinct, but possession of these are also the least secret information in the game.

Now, the real problem…

Oh yeah, this is all just setting the context.

A sensible move in Scotland Yard means not just working out where you should go, but where all the other pawns will go in response. For detectives working together, this can be co-ordinated but it has to be done so in response to ticket information provided by Mr X. ‘Oh, they took a taxi, then a subway, then a bus, then a taxi’. That puts a particular travel profile out there and the nature of the nodes on the map mean that it will only be possible to satisfy in some parts of the board. That’s only going to be worthwhile information if each player can actually see the board well enough to work out what’s feasible. With every move Mr X makes, the radius increases. It contracts again when Mr X’s position is revealed, but there’s a lot of movement until that happens.

So, where do you think Mr X is? Where is Mr X likely to go? What does that mean for your tickets? Who has easiest access to get to a prime location? All of that requires a deep appreciation of the board, who is where, and what options they have.

For Mr X it’s made even more difficult because you need to have an idea of that for every detective and nobody will be able to help with it without you revealing important information about your own location.

Sorry, Scotland Yard has to get an F grade from us.

Cognitive Accessibility

Another world of hurt is to be found in here. Let’s talk about detectives first.

In terms of fluid intelligence players need to construct network graphs of locations from the clues they have, anchored around the known locations of Mr X in previous rounds. They need to move to limit options for Mr X and deduce a location. This while carefully managing their tickets to make sure they don’t give Mr X more opportunities than they need and don’t leave themselves short later on. This at least is a collaborative activity but I don’t think you’d get much out of the experience by having other players order you to particular locations like a player-owned NPC. Making a meaningful contribution to the strategizing involves overlaying an understanding of movement possibility onto the board and comparing it to the deductions other people have made. Building this network graph is cognitively demanding, and holding it and alternatives in mind is a massive burden on memory.

The game itself is not overly complicated, and there isn’t much else players must do other than this. It’s a massive ask though and I don’t think it’s a realistic expectation for anyone with even minor impairments in either of our cognitive accessibility categories.

This is absolutely multiplied for Mr X who must work alone, keep track of the consequences of their own actions, and ensure the auditability of their trail at all times. They get to largely forget about the economy of tickets, but the counterpoint of that is that all of their movements are correspondingly more important.

This said…

It’s possible to play this game with a Mr X that is more interested in the fun of the chase than they are about winning. An adult playing with children for example might make bad decisions just to give a group of young detectives a thrill about finding a lead. In a competitive environment, a good Mr X is difficult to catch, as it should be. In a looser environment, a good Mr X can simply be fun to catch. It’s also entirely possible for Mr X to be captured very early, either through bad luck or bad planning. If the fugitive doesn’t mind making things easy for the detectives a lot of the cognitive cost scales down. Not to the point that I’d necessarily recommend it in the event any player has a fluid intelligence or memory impairment, but that it wouldn’t necessarily be the worst choice for game night.

We don’t recommend Scotland Yard in either of our categories of cognitive impairment, and for competitive environments we’d be even more intensely critical. If you have a Mr X determined to aim for group fun rather than individual fun though, it’s not a lost cause just because the network graphs players would need to hold in mind would be a lot looser and more forgiving.

Emotional Accessibility

This can be a one-sided game, but it depends on player counts which side gets the advantage. More players slants it towards the detectives, fewer towards Mr X. It’s specifically designed as a game of cat and mouse, and while it’s not perfect information it is a game that is, after setup, entirely deterministic. A bad winner can certainly make the claim that they won because they were smarter and more skillful than others. Those that make competition in a game into competition between personalities may not be a good fit if someone with an emotional control disorder is present.

It’s possible to lose the game unexpectedly and by accident. I think the first time I played this with Mrs Meeple she caught me within about four turns because I’d been foolish enough to move somewhere she’d obviously check out herself. I did feel pretty embarrassed at that. Our next game lasted for the full length of play. In that second game, the frustration primarily came about through the dearth of useful tickets possessed by detectives – when the thing stopping a capture is that the buses just aren’t available because your commuter pass has run out of credit. That’s especially annoying because of how unrealistic it is.

Being one of the detectives benefits from moments of revelation. At certain points the location of Mr X is made fully transparent. However, a smart player will know this is coming and put themselves in a position to mitigate it almost instantly – playing a double ticket for example, or a black ticket at the docks that maybe moved them miles away or just let them slink back into the city streets. It can be frustrating to know how close you are and yet have the target slip through your fingers.

None of these are major issues though, and if you’re playing with a good natured group they’re likely to be non issues. We’ll recommend Scotland Yard in this category.

Physical Accessibility

Players have to move their pawns around a very dense, large board. Only one pawn can occupy any given space though and there’s nothing else on the map. As such, precision is not required although reaching from one side to the other may be an issue.

Players also must manage their tickets when making moves, which means spending from a limited supply for detectives and retrieving spent tickets for the fugitive. This doesn’t require any particular precision.

The big problem here for Scotland Yard is likely to be for those with difficulties standing and manoeuvring around a board because you’re going to have to get up and close to work out what options you and your opponent(s) have. Nodes are tiny and may be right at the corners of the board, and each comes with a relatively dense knot of information indicating available travel options and routes. It’s easy to ask ‘Where can I go from that node’ but the sense of making a move is usually contextual. No point moving somewhere that only has taxis if you won’t have any taxi tokens left, as an example. The best node for you to pick depends on the best node for other people. That means a lot of leaning in and examine the board, no matter who you are playing.

So, if precision of movement is an issue Scotland Yard is almost certainly going to be fine. If gross motor control is a factor, then the story is a little less positive depending on the exact nature of impairment.

That has a corresponding impact on verbalisation. Scotland Yard is simultaneously optimal for verbalisation (everything you want to do can be described) and terrible for it (knowing what you want to verbalise involves huge amounts of information that may need to be gained through close inspection of the board). ‘Move my pawn via the bus from 124 to 154’ is easy to indicate but knowing that’s a possibility or something worth doing is less so.

For the player acting as Mr X, there is also a need to write a clear number in the tracking pad and cover it covertly with a ticket so nobody can see what it is. Moving this pad too clumsily may reveal critically important information to nearby players and this will completely ruin the game for everyone.

So, there are problems but they aren’t problems with universal applicability. We’ll very tentatively recommend Scotland Yard in this category, but please bear in mind the need to look closely at a large board and interpret its meaning in a mesh of context set by the other nodes.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

Yeah, it was a bad idea to name the fugitive ‘Mr X’, especially because ‘Mr E’ at least gives you ‘Mystery’ when you say it out loud. ‘Mr Y’ gives you ‘Mister Y’ when you say it. In any case, the ‘Mr’ is unfortunate and unnecessary, especially with the assumption of masculinity in the manual.

Mr X is represented on the tickets as a shadowy fugitive figure, but explicitly as a man on the box.

I would have liked a more generic name for the fugitive, and with a degree of ambiguity about its presentation. It would have been so much cooler that nobody even knew if they were looking for a man or a woman. Everything else in the game is a fairly standard representation of London.

In terms of cost, this is a mass market game and you can pick it up for a price to match – £21 at RRP and often available for £15 or less. It’s all but impossible to criticise at that price point for the amount of game, and amount of player count support, you get in the box.

We’ll average all this out to a recommendation. Just.

Communication

No literacy is needed during play, but detectives will need to communicate with each other to coordinate strategy and Mr X will need to be listening keenly to what they say to develop an appropriate counter strategy. Detectives as a result will likely want to whisper or otherwise obfuscate their discussions. That means that articulation and comprehension is likely to be stressed during the course of play. It would certainly be possible to house-rule this phase of the game to ensure that all talk was genuinely open information but with a corresponding impact on the experience.

That said, you can play the game in silence (and indeed likely will in a two player setup) and it’s possible to be an effective Mr X without taking any notice of what the detectives say. After all, if they didn’t want you to hear it they’d be wary of saying it. Maybe not hearing their misinformation is the safer course of action.

We’ll tentatively recommend Scotland Yard in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

Any intersection with physical impairment is likely to be a problem, because close inspection of the board is going to be correspondingly more important. Colour blindness will require more checking of the pawns and locations. Communication of movements will be more difficult but also so will gathering an appreciation of the options available. Feeling a disinclination to check the board too often will exacerbate emotional issues. Mostly though any intersectional issues are dealt with via their individual category recommendations.

Scotland Yard has an unpredictable play time. It might be over in a few turns. It might last all the way to the end. The length of each turn also depends on how much thought players are prepared to invest in their activities. It can easily be long enough to exacerbate issues of discomfort. It does though reasonably easily permit a player dropping out provided they are one of the detectives – another player can simply action their turns, or they can be converted mid-game into one of the ‘Bobby’ NPCs that are used at lower player counts. The latter of these is the cleanest compensation in terms of activity around the table but also the one with the biggest late-game impact. Bobbies don’t need tickets to move.

Scotland Yard also gracefully supports players tagging back in – they can simply resume control of the pawn they relinquished before.

Conclusion

Sadly, Scotland Yard isn’t a paragon of accessibility and some of that is definitely down to design imperfections. It’s a shame that we don’t have more positive things to say here, but we also shouldn’t be too quick to form judgements. This is the first hidden movement game we’ve looked at on the blog and as such it’s not possible to say yet which of these issues are unique to Scotland Yard and which are natural consequences of hidden movement games in general.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | B- |

| Visual Accessibility | F |

| Fluid Intelligence | D |

| Memory | D |

| Physical Accessibility | C- |

| Emotional Accessibility | B |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | B- |

| Communication | C |

That said, I’m calling it early and I will say that it’s possible to have a hidden movement game that isn’t quite so visually inaccessible. The Scotland Yard board seems like a poor design for that goal and I expect other games to make some improvements in this category at least. We’ll see though as we gradually make our way towards other, more modern, interpretations of the concept.

We gave Scotland Yard three stars in our review. A good game that unfortunately doesn’t really hold up to its best after twenty five years of other games cribbing from its design innovations. It’s an easier game than many of those that have trodden its secret routes, but unfortunately it has a lot of inaccessibilities that mean we can’t really recommend it too enthusiastically your way. C’est la vie. Maybe the next game in this genre will have better news for fans of this type of game.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.