Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Dungeons & Dragons: Rock Paper Wizard (2016) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Light [1.33] |

| BGG Rank | 3324 [6.57] |

| Player Count | 3-6 |

| Designer(s) | Josh Cappel, Jay Cormier and Sen-Foong Lim |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

While it’s not entirely successful as a sustainable game experience, Rock Paper Wizard does offer anarchic fun in short bursts. There’s a fair amount of personal wish fulfillment that comes from pointing a closed fist at someone and yelling ‘Fireball’, even if it doesn’t incinerate them quite as efficiently as you might hope. We gave Rock, Paper, Wizard three stars in our review – I think it’s basically okay and that’s a hill that I’m willing to die on as the meteors swarm all around. You didn’t come here for us to talk about how much we like the game though – you’re here to find out how likely you are to be able to play it. Let’s find out – ACCIO TEARDOWN!

I know accio isn’t a D&D spell, I’m just messing with you. I just love Lord of the RIngs too.

Colour Blindness

Colour blindness isn’t a serious issue but there are some minor missteps that impact in a small way upon ease of gameplay.

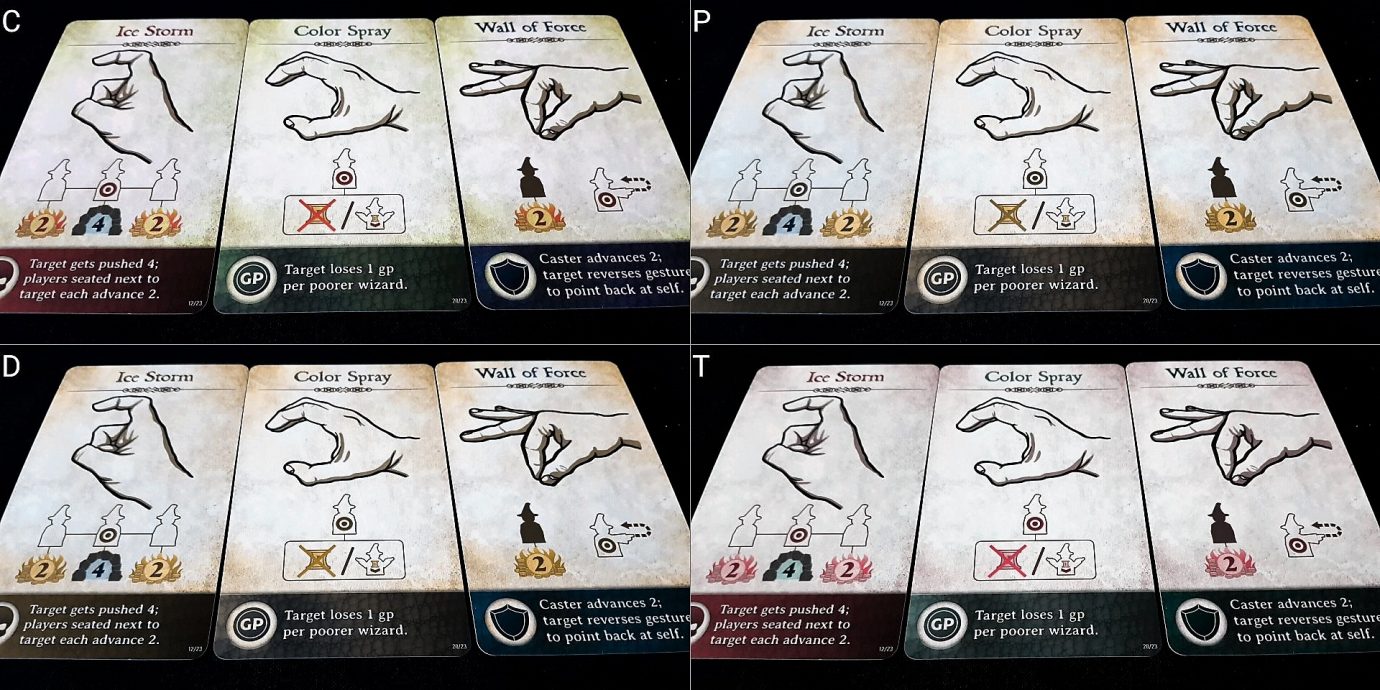

The spell book cards that you deal out use colour as a channel of information to classify their effects. Red indicates an attack spell, green represents something with economic powers, and blue indicates defence. The hue and tone used for these is going to lose this information for players with any kind of colour blindness:

I cast magic missile at the darkness

But, while this has a small impact on the ease of classification at a glance, it doesn’t actually make much of a difference because an icon and fully descriptive text is provided to supplement this. It makes identifying the classification of the spell you want a little bit more time consuming but otherwise doesn’t contribute negatively upon the game experience.

A wishlist of wizards

Each of the wizards you can select to control has their own unique art profile to go with them, and icons are also used to differentiate individuals. This is perfect for the cards you put in front of you to identify your role but less so for the standees that are used to show your location in the cave. While they are absolutely possible to differentiate, you’ll be doing this usually at a distance and using only a thin token to do so. Upon inspection you’ll be able to tell which is which, but close examination of markers will likely reveal something of your intention to other players. The art is distinctive, but at the distances these pieces will generally be one mass of art isn’t necessarily easy to differentiate from one other mass of art without colour clues.

These issues don’t seriously impact on gameplay, and with familiarity they go away. In the short term you can support ease of play by mapping location on the cave track to player order around the table. There are compensations, in other words, that will bridge the slight information gap until it closes of its own accord. We’ll strongly recommend Rock, Paper, Wizard in this category.

Visual Accessibility

Interestingly, this is a game that is almost entirely inaccessible in terms of its visual components and yet still entirely playable for players with even total blindness. It won’t be possible to do so without some compensations or support from the table, but it’s absolutely possible. Before we get to that, let’s discuss components.

See how well differentiated the places aren’t

First of all, the board you use for determining player location is very poorly designed from a visual accessibility perspective. Contrast is low for the lines that indicate spaces. The first three and last three spaces of the board are ‘highlighted’ to show areas in which players get pushed towards the centre at the end of their turn but there’s virtually no differentiation on the board unless you know to look for it.

The individual player markers have identical form factor, and there’s no way to tell one from the other by touch. You’ll be able to work out where wizards are distributed around the cave, but not which specific wizard is where. That’s important game information because the spell you want to cast is going to be influenced by where everyone is. It’s not as simple as deciding ‘I cast a fireball’. You also need to decide who you want to target with it. Sometimes you also want to know who’s going to get splash damage because they’re sitting next to someone. Relative position of players is important in decision making.

A budget necronomicon

The spell book too offers no tactile clues to players as to which spell is which – all cards are identical. The information presented on the card is well contrasted and the gesture diagrams are clear and easy to follow. They do though sometimes have a degree of physical configuration that makes them difficult to precisely emulate. The iconographic information that accompanies the spells is sometimes helpful but just as often entirely mystifying without the accompanying text. If some degree of visual discrimination is possible then inspection with an accessibility aid will be fine.

So, none of that is encouraging from the perspective of visual accessibility and yet the game is entirely playable with support. There’s relatively little information that anyone needs to know, and some of that information is going to be based on physical position of participants. Here’s what you need to know in order to make a sensible choice in Rock, Paper, Wizard:

- Which wizard is sitting where around the table

- Where each wizard is in the cave

- How much gold each wizard possesses, roughly

- Which spells are available

- The gestures to make with each spell

Of these, the fifth is entirely optional – all that’s needed is an unambiguous way for you to reference the spell you want to cast and in a way that doesn’t easily permit ‘on the fly’ changes as circumstances alter.

Who the hell is minting coins like this?

Coin tokens are accessible in that you can differentiate them all by touch including higher denominations. You’re only using these to keep score in any case, and so alternatives can be adopted if and when required. That piece of information can be queried at any point it becomes relevant.

The number of spells available depend on the number of players but there will never be more than five choices at any time. As such, on any given turn the table can offer a summary of the state of play reasonably easily. That can be comprehensive enough to make real decisions on what should be done even if none of the game information is visually available.

‘Raistlin is on space three. Polgara on space four. You and Hermione are on space five. Gwen is nearest the exit on space six. The spells we have available are, in order, Wall of Force which advances you two and reverses the spell of your target. Colour spray, which forces the target to lose a gold piece for everyone that’s poorer. Imprisonment, which makes the target give 1 gold piece to every poorer wizard. Antimagic field, which advances you two and then turns your target’s spell into a wild surge’

That’s quite a lot to take in but except for the position of each wizard this information is altered on a slow, incremental basis. On the next round, the Wall of Force spell will be gone and a new one will be added. That permits players to focus only on new information and continually reinforces the effects of existing spells. The first couple of plays of this will be slightly rocky, but gradually they will become much smoother as familiarity with the library of incantations is gained.

It’s still going to be the case that the game will need a sighted player at the table, but as long as that can be arranged the game is fully playable. The limitations and information required means that we can’t offer a strong recommendation, and the design fluffs in contrast and such mean that even our recommendation has to be qualified. Even the totally blind though can play this with some careful support and assistance.

Cognitive Accessibility

It is sometimes the case on this blog that criticism levied in a review turns out to be good for the accessibility profile of the game. So it is here. The chaotic unpredictability of the meta-game in Rock, Paper, Wizard meant that we couldn’t be too enthusiastic in our support for its design. However, while this makes it a flawed social deductive game it makes for a game where cheerful randomness can be just as effective as considered planning. If you play Rock, Paper, Wizard just for the fun of it then there doesn’t need to be a lot of thought to bring that about. The cognitive barrier to enjoying the experience is very low. You don’t need to play well to have fun.

However, there are cognitive costs associated with play and they are going to need support from the table to deal with in many cases. There’s both an associated level of conditional numeracy and conditional literacy required. The effect of certain spells is going to depend on their position in the spell book and the specific wizard against which they are cast. Some spells have an impact based on who is sitting beside the target, others based on the order in which they are triggered. The subject of a spell may change in the course of the round because targets such as ‘the richest wizard’ are evaluated when the effect happens. The description on the card will explain how they work but there is a cognitive evaluative cost when aiming at ‘the target’ or ‘the poorest wizard’. These terms don’t relate to specific people around the table – they refer to shifting qualities of people around the table.

There is an intense unpredictability that comes from what the spell you choose ends up doing – properly, you’re looking to anticipate what everyone else does and then pick the spell most appropriate for turning that outcome to your favour. Realistically this is all but impossible because everyone else is doing the same thing and as such the outcome is far more about anarchy than analysis. Picking a sensible spell though is useful but what is sensible will change from round to round, wizard to wizard, and casting order from casting order. The value of particular outcomes in particular shifts with cast order – as an example, there’s no point reversing the gesture of your target if their spell triggers before yours in the round. Even if you actually get to trigger the spell as intended, it won’t necessarily have the outcome you desire. Let’s say you cast a spell on the ‘richest wizard’, and then as a result of other effects that turns out to be you when the spell evaluates – that sort of self-inflicted wound is common.

Numeracy comes into play both in terms of evaluating the wealth of wizards and in terms of calculating effect. Some spells have an impact that depends on how much gold a player has, others based on where a spell is located in a spell book. As such, the power of spells themselves might vary over time, as might the impact if a wild surge is triggered.

All of these complexities can be explained in simpler terms or in round-about ways without needing anyone to know too much about the specifics. Whether someone moves one or two squares is rarely the key deciding feature – it’s the direction of travel. You’ll almost always just pick the biggest number that sends someone in the direction you prefer and then not accomplish your goal anyway.

So, while you probably won’t achieve the goals you set for yourself in a round, the act of meaningfully choosing something to do is quite cognitively expensive as is building up a model of what you think everyone else might be planning to do. The actual outcome may as well be based on a roll of the dice in many circumstances, but creating the illusion of meaningful decision making is an important part of that being fun.

We’ll tentatively recommend Rock, Paper, Wizard in the fluid intelligence category with a stronger recommendation for the category of memory impairments.

Emotional Accessibility

Rock, Paper, Wizard is a game of being able to cheerfully accept the consequences of frustrated ambition. You might manage to construct a master plan that results in someone running in to the hoard only for you to swap places and get the loot. You might talk other people into supporting a plan that seems to work for them but mostly benefits you. You might anticipate a spell coming your way and counterspell it, or force a wild-surge that works to your favour. You might do any of that. You might do all of that.

Problem is, you almost certainly won’t and it’s almost never going to be your fault. The only time you are guaranteed to get off the spell you intend is if you’re the first player. Every other time you are at the mercy of the collective actions of the table. If someone casts the same spell on you that you are casting on them, it gets turned into a wild surge. Some spells change the target of a gesture. That might mean that you’re casting a spell on someone you didn’t intend to grievous effect. Imagine you want to swap positions with you and the leader, and because of someone else’s spell you end up swapping positions with you and the person farthest away. Imagine being forced to cast a spell on yourself, or trigger a wild surge that actually does more benefit for everyone else than it does for you.

The question you need to ask yourself is ‘how funny does that sound?’. For some it will be ‘That sounds hilarious!’ and if so you’re right – this is a funny game where nobody accomplishes what they want and everyone laughs about it. If you think it sounds infuriatingly frustrating, you are also completely right. This is a game where everyone at the table can end up ganging up on you even if every single one of them picked a different target. It’s just in the nature of the thing. In the end the outcome of your action will be decided by the table as a whole, not by anyone individually actually sitting at it. Rock, Paper, Wizard is one big long ‘take that’. If you play games to win, Rock, Paper, Wizard is a singularly poor title for consideration in this category.

If however you just play to have fun, there’s not much to worry about in terms of the design. You can’t take winning and losing seriously. Even difficulties in social situations of bluffing and reading intention don’t have much impact because of the swirling eddies of variability that come into play. Imagine it like a game of One Night Ultimate Werewolf where you can try to accuse someone of being the robber but somehow manage to out yourself as a werewolf. With ONUW it’s important to be able to ascertain truth and lies. With Rock, Paper, Wizard there’s no chance that will work consistently. You can properly anticipate what 80% of the players do, but the one you don’t will change the outcome dramatically. A single wild surge in a round can make the entire outcome look as if it came from an entirely different spell book.

We’ll recommend, just, Rock, Paper, Wizard in this category but bear in mind – this is not a game that will at all be emotionally accessible to anyone that plays games to win or demonstrate mastery. This is a game that expects people to screw up and laugh about it.

Physical Accessibility

This is our trouble area for Rock, Paper, Wizard and it’s not going to be a surprise why. The core method of interaction is thumping your fist against your palm to the chant of ‘Rock! Paper! Wizard!’ and then revealing a hand gesture matching the spell you want to cast. That’s a problem only if mobility in the hands is limited – the game is otherwise completely physically accessible. If physical impairment is linked to walking or locomotion, there are no troubles that are directly caused by the game design.

I’ll spray puce everywhere

So, let’s drill down into why this Rock Paper Scissors interaction is a problem for everyone else. For one thing, it’s a real-time system – everyone has to do it at the same time. For another, it depends upon simultaneous revelation. If someone is slower than someone else in revealing their spell it can have genuine game impact. ‘Oh no, they just revealed they’re about to cast the same spell as me, so I am going to change it now that I know what they’re doing’. Real time and simultaneous revelation creates a number of accessibility implications that don’t have obvious solutions within the context of the game components provided.

Within Rock, Paper, Wizard there’s a third problem – the gesture must also identify a target. It’s not enough to unambiguously identify a spell, it has to be aimed at someone. That means that players with the freedom of movement in their hands to make a spell gesture are also going to need sufficient range of movement in their arms or upper body to indicate everyone else at the table. They need to do this at the same time as everyone else while making a hand gesture that might perhaps be complex or uncomfortable. To be fair, there are relatively few gestures in the game that are especially complex but it they do range from a Vulcan style greeting (the Polymorph spell), the ‘call me’ gesture with thumb and pinkie (the Confusion spell), the ‘cuckold’s horns’ (Burning Hands), and crossed fingers (Dimension Door) in an otherwise closed hand. All it takes is a minor degree of rigidity in the digits for some of these to be difficult to do, especially at speed.

Just picking a speck off your jacket, nothing to worry about

This isn’t something that verbalisation can solve either because it has to be done simultaneously. It’s certainly unambiguous to say ‘Cast Fireball at Chad because Chad is the absolute worst SHUT UP CHAD WE ALL THINK THAT’. By the time that you’ve rendered a verbal explanation of your spell though people will have had revealed enough information of their own intention for you to change your mind mid-sentence. Even if you’re not going to do that, people might not necessarily believe it.

This is almost certainly a solveable problem but it’s going to involve a fair degree of impact on game flow or sheer awkwardness of compensation. The gestures are not actually required for play as long as you can indicate the spell you want to cast, and so you might write in advance the name of a spell. This would then require you to just say the name of the target. Or perhaps you could write both down in advance. However, one aspect of an RPS style game is that you get a chance to change your mind as you’re chanting based on subtle (and perhaps imagined) clues in the body language of your fellow players. A player that has to write down the spell in advance loses that opportunity. If you see someone suddenly grinning at you when they say ‘Paper’ a physically impaired player won’t be able to change their written spell to the counter spell they suddenly wish they had cast. Chad on the other hand (damn you, Chad) would have been able to think ‘Oh no, oh no, I’m going to fireball instead’. The physically impaired player is always going to be at a disadvantage here.

One of the problems with our ‘recommendations’ here on Meeple Like Us is that a single letter grade doesn’t accommodate situations where the physical accessibility issues are highly conditional. Many players with profound physical accessibility complications will be able to play Rock, Paper, Wizard with absolutely no trouble because their mobility in arms and hands is fine. Others with relatively minor impairments localised to hands may find it entirely unplayable because of the speed and complexity of the spellcasting. Somehow, we need an overall grade to encompass both extremes and that doesn’t work at all.

Our letter grade for this is going to suggest players with physical impairments stay away from Rock, Paper, Wizard but bear in mind that if someone has a full range of motion in their hands and arms they’re likely to be able to play it without any difficulty.

Communication

The chanting down to the revelation of the spell isn’t strictly speaking necessary, and all the text on the cards is accompanied by (occasionally inscrutable) iconography that graphically depicts the game effect. As such, there’s no formal need for literacy during play although it does help.

We’ll strongly recommend Rock, Paper, Wizard in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

Unusually for a game with roots in fantasy RPG,the character art doesn’t overtly sexualise the women it has available as wizards. At least, I don’t think it does – I find the art to be very busy and it’s hard to make out a lot of detail in the tiny tokens you get to look at. The colour schemes chosen mean that it’s difficult, at least for me, to pick out details. Suffice to say that none of the wizards look like they turned up on the battlefield in lingerie and that’s an improvement over a lot of D&D style game art.

A wizard’s ball

Gender neutral pronouns are used through the manual in the direct explanations, and genders vary in the exemplar text used to explain how to interpret game actions. As such, it doesn’t raise any of our usual red flags.

Rock, Paper, Wizard requires a minimum of three players and maxes out at six. It definitely benefits from more as opposed to fewer people though – with a smaller player count you have greater opportunity to accomplish the tasks you set out, but it turns out that’s less fun than you might think. You want enough anarchy in there to bring out the comedy. Luckily though it’s very rules light and as such people can be up and playing, regardless of their experience of gaming, within minutes. This means you can often find a reason to play it in circumstances where other games might be a more troublesome fit. The RRP is around £20, and given the player count it supports and the convenience with which it does so. It’s a good proposition in terms of value for money although bear in mind this is something you’ll dip into on occasion rather than it being a cornerstone of your library.

We strongly recommend Rock, Paper, Wizard in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

This is a little more complicated than usual due to the very precise way in which physical accessibility issues manifest in the game. In normal circumstances we’d say something like ‘if visual impairments and physical impairments intersect then it’ll be difficult to read cards and the like’. That’s true, but with some careful support from the table you don’t even need to be able to see them. The only real compounding condition is if physical impairment relating to range of motion in the hands intersects with a communication impairment related to articulation. In that circumstance, a different approach would be needed to offer simultaneous revelation of a targeted choice. We wouldn’t recommend the game under those circumstances for the reasons we’ve already outlined.

At an approximate play time of thirty minutes, games are short and low-stress. You’re not carefully making decisions to minutely advance an agenda – you’re just picking a spell, aiming it somewhere amusing, and seeing what happens. As such, it’s unlikely to exacerbate issues of discomfort or distress. However, if playing with people embodying a range of accessibility considerations it’s almost mandatory to offer a degree of flexibility when it comes to lapses in physical accuracy or speed of revelation of gestures. Everyone is going to need to be willing to give other players the benefit of the doubt if the occasional stresses of making hand formations within real-time constraints leads to mistakes. Trust me – you don’t lose anything in letting people off the hook with this because you’re not going to accomplish what you wanted to do anyway most of the time.

Conclusion

I feel a little bad about the grade given here in the physical category because for a large number of players none of this will at all be an issue. On the other hand, even a tentative recommendation has a risk of steering players towards a game that might be entirely unsuitable. I’ve said this several times elsewhere on the blog but please don’t put too much stock in the letter grades. It’s the discussion that accompanies each that contains the actual information needed to make what I hope is an informed decision as to a game’s suitability.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | A- |

| Visual Accessibility | B- |

| Fluid Intelligence | B |

| Memory | B- |

| Physical Accessibility | D |

| Emotional Accessibility | C+ |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | A- |

| Communication | A |

Nonetheless, even with that potentially troublesome category we can see that Rock, Paper, Wizard actually comes out of this rather well. Much as with Santorini, I went in with certain expectations that were confounded by a full consideration. We’re past one hundred games assessed for Meeple Like Us now and I’m still coming out of a teardown genuinely surprised by what it showed. This is why this topic consumes my dreams – every day is a school day.

We gave Rock, Paper, Wizard three stars in our review – it’s a social deduction game that permits no real opportunities for deduction and that’s a problem. However, it can also be very funny and that saved it from a considerably more bruising rating in the final reckoning. Funny excuses a lot, and there are lots of opportunities for laughing your way through a game of this. It won’t quite satisfy the need for ingenious incantations that scour the flesh from the bones of your foes, but at least it’ll make you more cheerful about your dumb muggle incompetence. Thanks for reading, and if you see the smouldering remains of burning house-elves on the way out of the blog I swear it had absolutely nothing to do with me.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.