Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Red7 (2014) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.69] |

| BGG Rank | 887 [6.87] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Carl Chudyk and Chris Cieslik |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Asmadi/Lucrum European English edition

Introduction

Red7 is Fluxx if Fluxx had been put out by a designer that understood how fun works. We gave it three and a half stars in our review – it’s cheap and cheerful and offers a good deal of well crafted fun for its simple rule-set. There is definitely a lot to like about Red7 as a game, but our real concern here has to be Red7 as an accessible prospect. Sticking a speculative finger into the box and swirling it around for a taste test highlights a whole host of problem areas, but how does it perform in practice? Let’s find out!

Colour Blindness

Red7 is fully colour blind accessible despite being a game all about the precedence of colour. It’s not perfect in this category, but every time a colour is used it’s accompanied by the text description of the colour. There is no part of the game where colour alone is the sole channel of information.

What’s the ROYGBIV here?

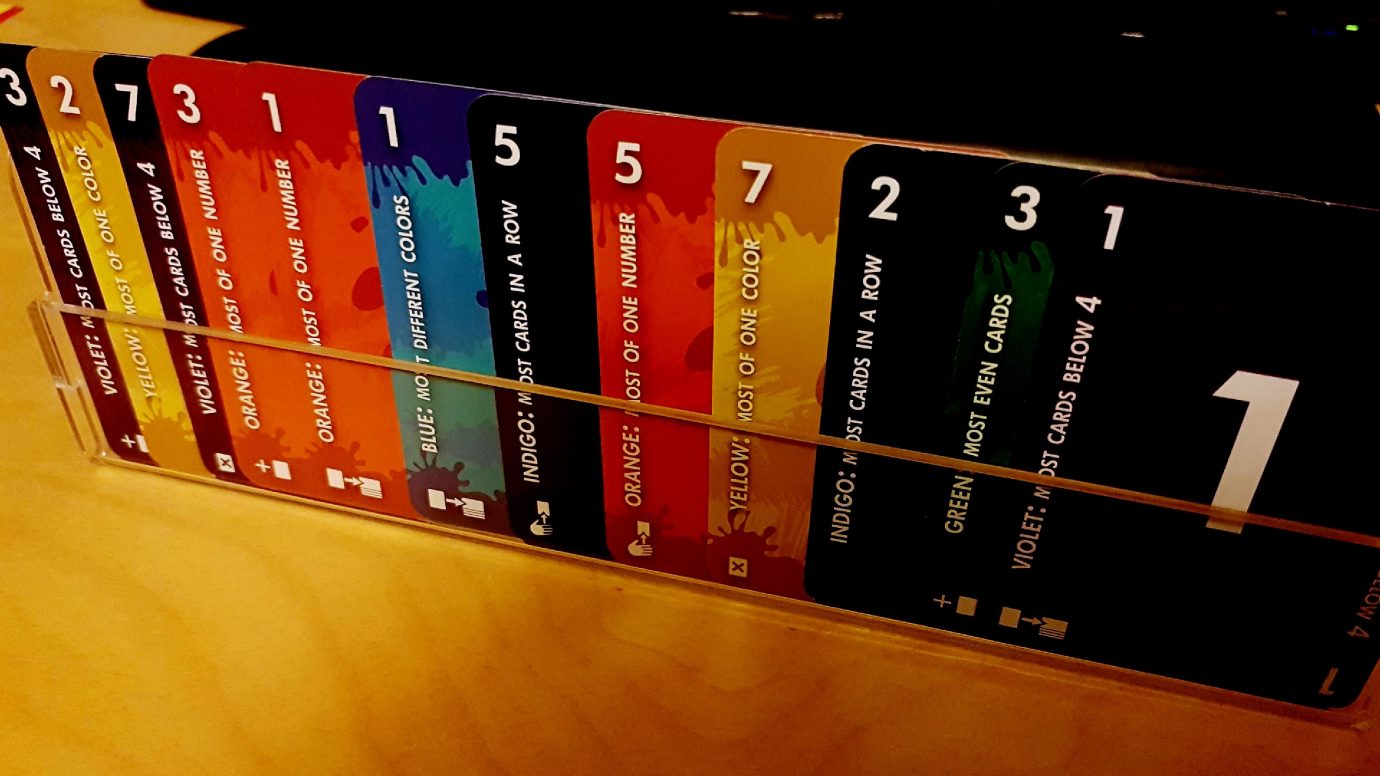

However, there is definitely an ease of play impact that comes along with the cards being so brightly coloured – those with fully chromatic vision will be able to see at a glance win states of each player much more easily than those with more restricted colour discrimination. For example, consider this semi-standard layout of a four player game:

Winning! Am I? Someone?

Win conditions include ‘most cards of a different colour’, and ‘most cards of the same colour’,. Deciding who is winning is determined first by face value and then by colour precedence. The current rule in place is blue: ‘most different colours’, but at a glance someone with Tritanopia might think it’s a green card active (most even cards). Someone with Protanopia might think the left hand side tableau contains only two colours, someone with Deuteronopia might think the top palette contains only two. Lighting conditions are important here – in clear lighting it’s usually possible to tell one card from another when it’s adjacent to others of that class, but part of the trick here is being able to tell what colours are present independent of a known reference point.

Read ’em and weep

But as I say, this is an at a glance problem and there is no real time component to Red7. You can fully investigate the state of the game without asking anyone a question, and even colour contrast between the splotches on each card can help differentiate – consider the splotch on the green six versus the blue six and you’ll see the green one is far darker than the blue. With familiarity this is an issue that will go away.

Red leader standing by

The splotch patterns though represent something of a missed opportunity – they could have differed on each of the colours to give another channel of information that would assist in this at a glance problem. Minor as the issue is over the long term, improvements are possible still.

We’ll recommend Red7 in this category – it’s fully playable, but the colour coding by name is going to have an issue on game flow that can’t be entirely discounted.

Visual Accessibility

Colours are well contrasted and text is presented in a large, readable font. Background ornamentation acts as a kind of letterbox for the numbers too – some colours (yellow for example) could be more distinctively brought out from the background but certainly for close inspection the cards are almost as visually accessible as they could be. That’s not useful still for those for whom total blindness must be considered. Every single piece of the game state is visual and the ever shifting nature of rules and palettes makes it difficult to represent the state verbally. As is often the case, we’d advise those with total blindness to consider other games.

There are a couple of small missteps in the visual design although they are resolved mostly by context. For example there’s no underline on the six to show its proper orientation, but there are no nines in the game so it’s not a problem telling them apart. I personally on several occasions though forgot that was the case as my brain, on autopilot, told me I’m doing a comparison against a green nine. That’s a tiny thing, but accessibility in this design space is much like hitting the indicators in a car when there’s nobody else on the road – it should be done even if it’s not necessary because it means you are less likely to forget about it when it is necessary.

This isn’t intended to be suggestive

The biggest problem really in the game is going to be interpreting the cards at a reasonable distance – the canvas only contains a single card someone needs to worry about, but everyone will have their own palette in front of them and its composition is important in both colours and numbers. In a four player game, this will also be done at several orientations of the figures and this can add to the difficulty of ascertaining game state. You need to do this for every player every turn too because you need to be winning – you don’t just need to satisfy the win condition, you need to satisfy it better than anyone else at the table. You need to Charlie Sheen every single time your turn comes around. WINNING.

That said, there’s no real danger that comes from people simply stating their palette composition. That though links into the issue above of verbally relating game state. It’s easy for someone to say ‘I have a green two, a blue four, a red six and a blue seven’ but that’s a game state that needs to be comprehended via several lenses depending on the current and future rules of the game. That’s ‘two cards under four’, but it’s also ‘three different colours’, and ‘two cards in sequential order’ and so on. Properly laying out cards in a palette in front of players is a powerful aid here to interpreting the game state. It’s not that players wouldn’t be able to handle it, it’s that it’s going to be easy to miss important nuance. For example, that red six and blue seven has an implication for comparison that wouldn’t hold true if it was a blue six and a red seven. The way in which the information is verbally presented too might hide important features by nature of the fact you either do this chunked by numbers or chunked by colours. ‘I have two blues: A four and a seven’ instantly prompts by comparison by colour set rather than numerical progression. People could give their palette state in relation to the current rule, but importantly you need to be able to evaluate it according to all possible rules that you might be able to bring into play.

Some of this is offset for players with the ability to discriminate colour because these cards are reasonably vibrant. Even if the specifics of face information can’t be made out at a distance the colour makeup of a palette can help channel and shape a convention for reporting on palette composition. A workable system can probably be found for this if you really want to make the effort.

We’ll tentatively recommend, just, Red7 in this category for those with some degree of ability to discriminate visual information, but those with total blindness should steer clear.

Cognitive Accessibility

Red7 does one of my favourite things here – it offers meaningful scaffolding of game complexity that you can layer in to meet player experience and competence. The basic game of Red7 involves satisfying the rule with a palette. The advanced rules include card draws based on canvas changes and a scoring context. The ‘expert’ rules incorporate the icons on the cards to let players choose a new tactical context based on what they get from the existing game state. I’d prefer it didn’t imply a skill hierarchy in how these rule-sets are described, but as a system for permitting meaningful play for those with cognitive accessibility concerns I love this and wish all games did something similar.

What we need to address then is whether the standard game of Red7 is cognitively accessible, because the rest of the systems can be layered in later only if desired. The base game concerns only the normal playing of cards to the palette and/or the canvas, and the satisfying of changing game rules. There’s a small degree of literacy required for this as well as a reasonably high level of numeracy that is situational based on colours.

Let’s get this party started

Consider the layout above. This is a very early stage of a game, but already it’s showing some of the cognitive complexities that come into play. The player at the bottom of the picture is winning, because the rule is ‘the highest card’. However, in terms of pure numeracy there is a tie – it only evaluates to a win for the bottom player because of the colour precedence rules. Cards are evaluated by number first and then by the rainbow spectrum. While neither comparison is complicated by itself, the combination of the two creates an additional difficulty for players where fluency in numerate activities cannot be relied upon. This comparison gets even more difficult when evaluating ties in more complex rules, such as ‘most of one colour’ or ‘most cards under four’. The precedence of cards remains the same, but in that case the evaluation is against a subset of one set of cards versus a subset of another. It’s not an insurmountable problem, but it’s one that is likely to come up.

As far as memory goes, the only hidden game information is what’s still in the deck and in the hands of other players. The union of those two sets of data can be deduced from the game information available to any given player, and in any case you’re mostly making decisions based on open game information. There aren’t any particular memory burdens here that are specific to the game design because deck composition is largely transparent. That changes a little if using the optional scoring conditions, but as discussed those can be layered in only if appropriate.

Game flow is consistent, but game rules aren’t – there are seven win conditions that will cycle in and out of play. The important feature with this is that at the end of your round you have to be winning – every single turn you need to understand the game well enough to be able to make that happen. Many games permit someone to play along and only find out at the end how they did. Such games have a degree of flexibility built into game competence – you can have bad turns and still win. In Red7 that’s not the case, and the cost for not planning far enough in advance is that you’ll be eliminated from play. It’s an unusually high burden of expected competence even if the game itself is not especially difficult to learn. Given how the context of the rules can shift from turn to turn, this makes every single card play potentially difficult. Some changed rules can be dealt with incrementally – others need two or three cards before you could possibly satisfy the rule. You can always change the win condition to something easier to achieve, but there’s a lot of forward planning involved in doing that safely.

There is an issue with the hidden hands in Red7 in that sometimes you are in a position of being able to satisfy a win condition on your turn but not necessarily able to see that you can. The nature of the game makes asking for help in this respect highly impactful on play. It’s not necessarily impossible to enjoy Red7 while playing with open hands, but it would change the strategic component considerably. Having someone able to corroborate another player’s options would be a useful help here.

Having said all that it’s not as if any individual part of the game is especially complicated. With support from the table I suspect this is something that could be satisfying to play for players with a wide variety of cognitive impairments. In any case house rules could be used to make things a little less febrile. For example, draw a random card from the deck as a new rule every full rotation of the table. I wouldn’t be too comfortable in recommending it wholeheartedly, but I think it probably could be made to offer serviceable fun with some modifications in a wide variety of circumstances. We’ll tentatively recommend Red7 here for fluid intelligence, and offer a more solid recommendation for those with memory impairments only.

Emotional Accessibility

This is a game about player elimination, but rounds are quick enough that it’s usually not going to be a problem for most players. You don’t spend a lot of time sitting out on the fun – individual games are over in a few minutes in many cases, and it’s the culmination of what happens after several rounds that matters. There’s a good deal of luck in play, but the tournament style of the scoring system means this evens out over time. However, as with any game where randomness is a key feature, ‘over time’ is not necessarily comforting if you find yourself sucking the fuzzy end of the lollipop every time the cards get dealt. It’s possible that you might find yourself out of the game without even getting to play a card, and that is far from ideal.

This luck element combined with the way scoring works will eventually remove choice cards from the deck. This means score disparities can be quite high. At the end of a round, the winner remove all the cards from their palette that are used to satisfy the win condition. You then take the highest card of each colour and then tuck them under your reference card as your accumulated score. As such, if someone wins a card that makes use of most of their palette, for example ‘most differently coloured cards’, they might end up removing anything from two to seven of the highest value cards from the game for the next round. That can create a hugely distorting effect on end scores. It’s easy to resolve this by awarding points in a different manner (ten for the last player standing, five for the second last, and so on) but the standard rules will almost guarantee the person that wins first has a significant score advantage for the rest of the game.

Other than that, there aren’t any real worry points here in Red7 – the nature of play means it’s not possible to gang up on another player because every single turn you need to be winning and as such you can’t focus on disadvantaging any one specific player. There’s no bluffing or lying required to play, although there’s no reason that couldn’t be incorporated as general table talk. There are a few take that mechanics in the game, but their use is entirely optional.

We’ll recommend, just, Red7 in this category.

Physical Accessibility

Drawing and playing cards is the only physical action required, and it’s not especially intensive in either case. At most you’ll be drawing two cards at a time, and at most you’ll be playing cards to one or two locations. Your beginning hand size is seven, but the cards compress together nicely to ensure that even a single card holder will reveal all the meaningful information you need to make decisions.

Lots of space for lots of cards

If verbalisation is necessary, this should be fully possible – ‘play my second card to my palette and the third to the canvas’. Your hand is hidden, but acting upon it can be done externally by another player without them needing to see anything.

We recommend Red7 in this category.

Communication

There’s no need for formal communication during the game, although there is a small expectation of literacy associated with each of the win conditions. This is easily resolved with a crib sheet, and with familiarity the rules can be easily internalised.

We’ll recommend Red7 in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

There’s no human art in the game, and the instructions are presented in the second person form. Artwork is entirely based on colours and numbers, and as such there are no issues with representation of gender or ethnicities.

Every time I see this I think it’s a Star Wars spinoff

Red7 has an RRP of £10 and it really is great value for that money – sure, it’s just a set of cards but it’s such an approachable game that you can play it easily with a mixed audience of differing skill levels and still get something out of it. It tops out at four players, but it plays well at all of those counts and is light and quick enough that it can fit into even small gaps in your day.

We strongly recommend Red7 in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

Our tentative recommendations for both visual accessibility and fluid intelligence would be reversed if these intersected with colour blindness. The additional cognitive burden put on play in this respect wouldn’t make the game unplayable but it would certainly be harder to justify why anyone should consider picking it up. Red7 is colour blind accessible, but there is a cognitive ease that goes along with being able to perceive the colours without too much close inspection.

For those with both communication and physical impairments, the relative simplicity of instructions means that a wide variety of effective regimes can be adopted to indicate intention. You could fully play this game with nothing more than a tap or a click – one click for playing one card, two clicks to play two cards, and then another click (or series of clicks) to indicate the card or cards. As long as a shared convention could be adopted, the intersection of these issues need not prohibit players from enjoying Red7.

Play-time is very brisk – individual games can be over and done with in five or so minutes, and the length of tournament style back-to-back sessions is entirely configurable. Red7 is also designed with player elimination in mind, so it supports players dropping out – their cards won’t be redistributed to the deck, but that’s not expected of an elimination anyway. Five minutes though, barring accessibility considerations, means it can fit conveniently into even small gaps where conditions may have modulating severity.

Conclusion

Some of our recommendations are ‘skin of the teeth’ close, but we’d be prepared to recommend Red7 across the board, with caveats and careful warnings, to anyone that might fancy giving it a try. Some of those recommendations depend on house rules though, so bear that in mind if you fancy picking it up.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | B |

| Visual Accessibility | C- |

| Fluid Intelligence | C |

| Memory | B |

| Physical Accessibility | B |

| Emotional Accessibility | B- |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | A |

| Communication | B- |

In most respects, Red7 is a fine example of how good design can even make what seem inaccessible prospects playable. ‘It’s a game about colours’ seems like it would instantly be a problem for people with colour blindness, but here it’s not . Ut’s all about making sure colour isn’t the only source of information. True, it’s not handled flawlessly here but that just means that there’s room for improvement in a future edition. With a more obviously distinctive way to differentiate colours at a distance, I could see this moving up a grade in several categories.

We liked Red7 enough to give it a three and a half star review, which while good still puts it behind the other two Carl Chudyk and Chris Cieslik games we’ve looked at here on Meeple Like Us. One Deck Dungeon is great and Innovation is superb, but neither of those games did as well in their accessibility teardowns. Asmadi Games have a consistent record of putting out good and enjoyable titles, at least as far as we’re concerned. Red7 is among them, and if you think you can play I suspect you wouldn’t regret the purchase.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.