| Game Details | |

|---|---|

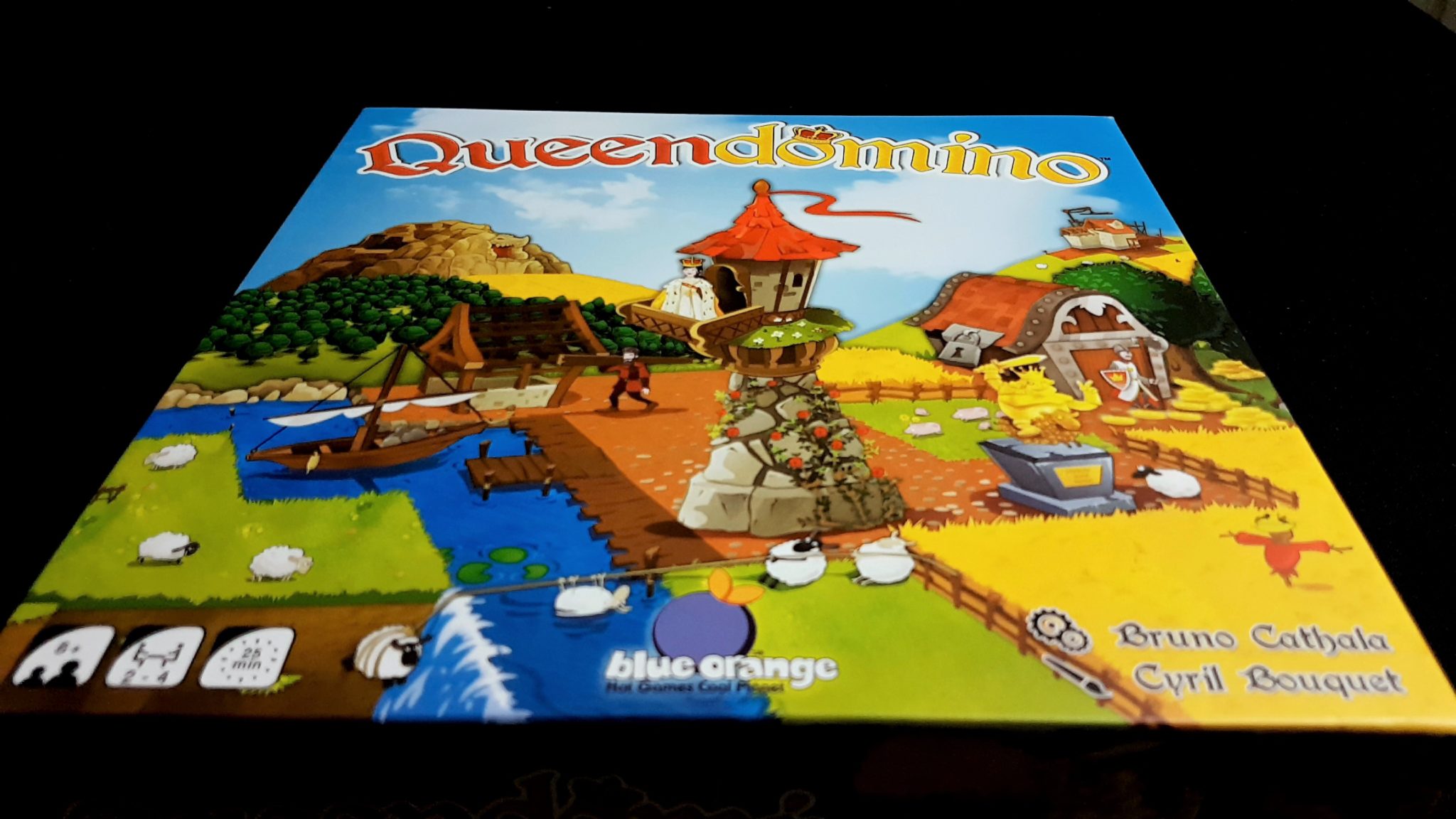

| Name | Queendomino (2017) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [2.05] |

| BGG Rank | 626 [7.16] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Bruno Cathala |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

It would be a good idea to check out our review of Kingdomino before you get your tea and your comfy slippers so you can settle down into our review of this. Queendomino is simultaneously a younger and bigger sibling to Kingdomino – brought into the world more recently but still possessed of a size and stature that dwarfs the older scion. However, it’s best to think of it as Kingdominio++ rather than a substantively different game. If it were released on PC this would be the Game of the Year edition and come preinstalled with all the borderline exploitative DLC that had been released over its lifetime. Go read the Kingdomino review because here I’m only going to talk about the original aspects that Queendomino brings to the table.

Back already? Okay… I’ll believe that you read it but if none of this makes any sense it’s pretty much your own fault.

Queendomino presents us with (almost) exactly the same enjoyable game at its core. It’s the Kingdomino experience with a few bells and whistles. You deal out tiles and you select the ones you want slightly out of sync with your ambitions. The result is a game that is like piloting a plane through a semi-controlled descent in the hope that you don’t end setting everything on fire. It’s just as satisfying here as the original, and that’s pretty darn satisfying. Nothing has been lost here in the upgrade as far as this part of the game is concerned.

On to this though Queendomino layers two new elements – a taxation system powered by knights, and town-building terrain powered by taxation. There’s a new terrain type in Queendomino and it represents unbuilt opportunities. At the head of the table sits the marketplace, full of tiles you can buy to configure both your little Queendom and the scoring regime that will reign at the end of the game. These city tiles can be placed on the new town terrain that will come up with the rations during the course of play.

The tiles that you buy from the marketplace will also provide you with knights and towers. Towers might be worth points later, depending on which tiles you claim. The main benefit though is the player with the most of these takes control of the princess and has a discount applied to every purchase from that point onwards. She also gives a sizable point bonus if you have her in your realm at the end of the game. Finally there’s a new dragon that can be used to destroy the tiles on the market that you desperately don’t want someone else to get, except the player with the princess never gets to invoke the dragon.

Got it? Good.

What exactly do you get then for all this extra complexity? Not as much as you might hope, really – the core of Queendomino is exactly that of Kingdomino, and it turns out that’s fun enough by itself without all this frippery and frittering around the edges. The taxation elements don’t add all that much, and the towers seem tacked on as an afterthought. The dragon is situationally useful but realistically a little difficult to employ to any genuinely effective end. There are almost always good options on the market early on in a round so you only occasionally really inconvenience anyone. If you employ the dragon too late then all the best targets will be gone anyway.

To be honest, I could have happily have done away with pretty much all of that. None of it feels like it really added much except extra inertia to my decisions.

Where Queendomino does become interesting though is in the new terrain and the tiles. The economy around these is far more cumbersome than can really be justified and I’d much have preferred something like ‘take a town tile when you play a town terrain’. The tiles themselves add a good chunk of strategic heft to the game and they do it in one of my favourite ways – by creating an asymmetry of value that mirrors and distorts itself within and between players.

Let’s consider how value works in Kingdomino – if I have five crowns in a grassland area, a grassland tile is worth five points to me if I can add it to the whole. If I have zero crowns in a grassland area, that grassland tile is worth zero points to me. Scoring is relative, as it is in most games, so you can mathematically plot out the value of each tile to each player if you are sufficiently curious. You can always take the optimal tile from those you have available. The only thing that stops Kingdomino from being an entirely solved game is the fact that you can’t reliably account for probability and the future is an unknowable beast. Still, there’s the value to me and the value to you and the goal is to maximise the difference in our favour, or minimise the difference in yours. The result of this is that over the long term we’ll all either be valuing everything roughly equally (as we try to normalise values between players) or valuing everything completely differently (as we capitalise on options other people aren’t taking). Whatever path we go down, it creates a fixed trajectory as the game goes on – value follows an analogue curve and the cost of changing that curve gets too great in the end-game to really contemplate.

Queendomino shakes that up by adding in town buildings that start to hugely distort the value, at erratic intervals, of terrain tiles beyond the relative simplicity of the availability of crowns. You can get tiles that give you bonuses for each separate territory in your realm, actually incentivising you to go for lots of low scoring areas as opposed to small numbers of high scoring areas. Importantly this is something you can do on a whim if you like – suddenly a patchwork quilt of a Queendom might be worth a small fortune in victory points and it happens in a single turn. It’s a violent market adjustment akin to a boom or a bust, depending on who gets the building and when.

None of the tiles that present you with town areas come with crowns, but some buildings will add crowns in there. Some tiles give values to knights and to towers, and some have a flat victory point total. The equation of value gets a lot more interesting as a result of this because the question stops being ‘how many points can I get for that tile assuming I continue to play as history pretty much demands’. Instead it becomes ‘what does that tile enable my opponent to do to the value of everything, and to what patterns of previous behaviour does it now add value?’.

That’s a lot more interesting of a question.

The answer to it means two of us might be desperate to get hold of farmland tiles, but we want farmland tiles in different ways. Me with my towns, I want to have lots of separate areas. I want tiles with singles. You with your crowns, you want tiles with doubles. These decisions start to become a lot more interesting when the calculation you perform takes on all the extra nuances that the marketplace enables. We might both be keen to get the tile with a crown, but for you it might be where your score actually comes from. For me, it might just be a single free point. The town tiles create something like a randomised spinner in the economy of the tiles. They put everything into higher energy states where decision making becomes more energetic. It turns out that’s just enough to nudge Queendomino higher in my affections than the comparatively more elegant Kingdomino. It doesn’t add much in the way of additional interaction to what is already a somewhat solo experience but it does mean the core hook of ‘evaluate a tile and pick the best’ gets a lot more interesting. Still though, it’s at the cost of all that knights and towers stuff and I really feel this element would have been better without any of that.

The game rules do come with several ‘royal wedding’ versions that allow you to play Kingdomino with Queendomino together. I can’t say it’s something I’d particularly recommend since in the end it just means more tiles or more players. Nothing changes particularly in the substantial elements of the game. Really it comes across as a kind of low-key way to encourage people to buy both games rather than a special thank you to those that already have the original. There’s certainly no reason I can see why you’d really need to go out and buy both to get the most out of either.

This is one of our occasional (relatively) brief reviews because the biggest and most enjoyable part of the game has already been discussed in another review. Queendomino is a standalone game in its technical sense but it’s not its own game with its own identity. Had it been sold as an expansion to Kingdomino, replacing specific tiles in the original with new town tiles, I wouldn’t have batted an eyelid. Had it gone down the Cities of Splendor route and had a series of optional modules you could slot in I probably would have been a good deal more enthusiastic. As it is, it stands as a competitor to Kingdomino and it’s occupying treacherous ground there. Kingdomino is the cleaner, more elegant, and more intuitive game. Queendomino is probably the more satisfying game to play but the cost is in an extra layer of cumbersome rules for only a slight overall improvement. I’d probably rather play Queendomino in most circumstances. The benefits it brings are just enough for me to enjoy it a hair more than the original. I suspect though I’d almost always recommend Kingdomino to others because that extra enjoyment isn’t at all proportionate to the additional overhead the taxation and towers introduce.