Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Planet (2018) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.58] |

| BGG Rank | 1659 [6.66] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Urtis Šulinskas |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

Planet is a visually striking game that is perhaps an ideal starter for newbies to the modern hobby. It’s pleasingly tactile, straightforward to play, and has such a distinctive hook that it’s hard to not want to play. We gave it three and a half stars in our review, noting that it suffers a little because of how difficult it can be to work out the scoring. Not mechanistically, but in terms of following the flow of land across a dodecahedron you rotate in all axes.

You better believe that’s going to have implications for the accessibility of the game, so let’s not dally any longer. Let’s check to see if this is a habitable planet for people with accessibility needs.

…

…

…

And then we’ll check out the Planet board game.

Colour Blindness

Colour blindness is somewhat of a problem, but not a critical one. All of the different landscapes come with unique patterning to accompany the colour. The problem is going to be one of exacerbating an extant issue with regards to knowing what is happening on the planets of the other players.

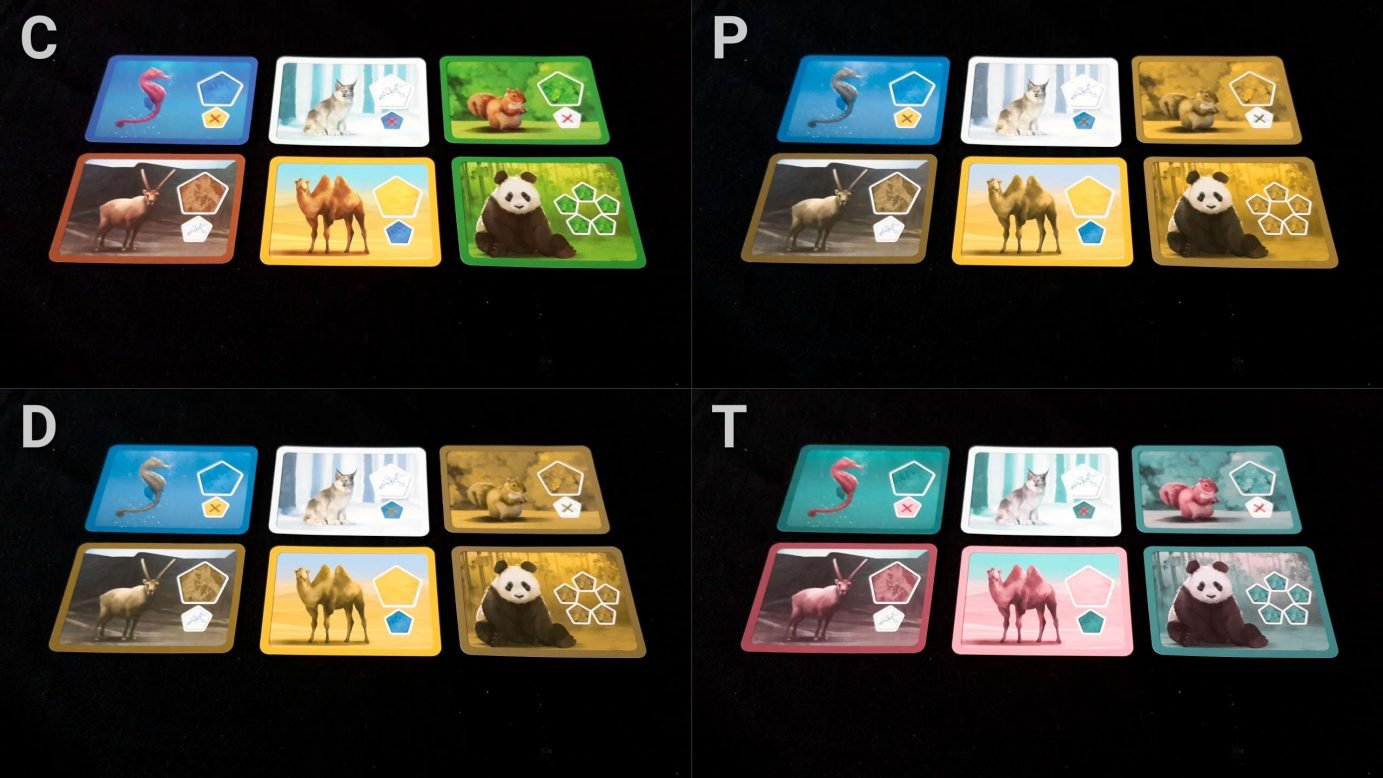

Note here that close up there is no problem for Tritanopes telling the difference between the sea and the grasslands. Similarly, grassland from desert for those with Protanopia or Deuteranopia. Farther away, it becomes more of an issue as you can see in this specifically Tritanope view.

It’s not impossible when directly facing a tile, but as the tiles retreat around the shape of the core it becomes increasingly difficult to work out. That has implications for strategic play – it’s already difficult to know what animals another player might be in a position to claim and the colour issues don’t help there. When focusing on your own planet, the problem is unlikely to be a major issue.

When it comes to animal cards there is a similar palette issue although it’s not actually a problem. Each card comes with an illustration of the animal and the appropriate habitat is thus deducible from context even if the specific patterning on the terrain is not always a suitable guide.

Habitat cards, those that indicate the tiles for which a player can score, are also an issue because the art that accompanies these is not obvious, at least to begin with. It’ll get easier with familiarity and short of conditions of monochromacy you can probably work it out through a process of elimination.

It’s not a clean performance but we can tentatively recommend Planet in this category.

Visual Accessibility

Hoo-boy, this is an awkward one. We already discussed in the review the problems that go along with trying to work out another player’s planet at a distance, and you can play reasonably well when focusing only on your own world. The problem there is that a dodecahedron is not a shape that is especially easy to visually parse since it has no fixed start and end point and the mere act of holding it obscures parts of the core.

There’s actually a lot of information contained on each tile, with more being brought into effect as tiles intersect. It’s important to know where a region flows when you pick a tile, and the implications for scoring when you select it. The contrast between individual segments of a region is very poor, but colour coverage can compensate to an extent – if over half of the tile is green it means that three or four segments are grassland.

A canny player will be calculating based on cards to come up in the future what kind of regions they want to stress. If there are a lot of aquatic species then a big ocean might be worth having – but only if you can satisfy the secondary condition on each upcoming card. That means that picking a tile, in optimal circumstances, is done with consideration of the implications for future scoring but also takes into account the tiles other players are likely to go for. The specific orientation of tiles too can have massive consequences, and you might only really know that when you look at how a full region connects across the entire planet. Placing a desert attached to an ocean might seem harmless unless it suddenly means that your biggest desert is no longer a suitable candidate for a card you wanted to claim.

For those with total blindness, the situation is worse still. There’s no way to tell the value of cards or tiles by touch. You could certainly pick and attach a tile to the planet core, but there would be no way of ascertaining its impact. Verbalisation of the offerings is straightfoward, but all but impossible to meaningfully leverage in a way that permits skilful play. The placement of a single tile can open or close opportunities across not just for the current turn but for all future turns.

We don’t recommend Planet in this category.

Cognitive Accessibility

Planet actually has a pretty unusual cognitive profile. Most of the games we look at tend to be poor from the perspective of fluid intelligence (complexity, strategic planning and so on) but it’s usually the case that memory is graded less harshly. It’s the other way around here, which is comparatively rare. The rules are quite straightforward, but calculating when someone should claim a card is much more difficult to do because of this weird memory issue.

Consider when a card is claimed by ‘largest ocean not connected to a desert’. That requires a player to find all their oceans not connected to a desert, find the largest one of those, and then count its segments. The problem with doing this on the planet core is that it’s easy to forget which regions you’ve already counted, and when segments within those regions have been added to the tally. The nature of the way it wraps around means that it’s also easy to miss regions that should be included or excluded. Over or undercounting segments is common. In the cases where there are multiple candidates that meet the win condition, this is compounded by the need to remember which is largest. The viability of any region will change wildly with the placement of a single tile so it’s not possible to deal with this incrementally.

More problematic still is the condition where players count the largest number of distinct, separate regions. There may be a half dozen or more of these on a planet and even I find this awkward to track myself. I try to place a finger on each region that has been identified but that results in an awkward claw and often I have fewer fingers than I need. Again, it’s not that it’s hard to count – just that it’s hard to count everything the right number of times.

At the end, players need to total up the number of tiles that they placed of their assigned terrain type, and that can be done by stripping all the tiles off the core and counting up the hexes. The difference in ease between this and counting regions on the planet is remarkable. It’s like taking a little day off in your head.

Aside from this, there’s no need for literacy during play, although numeracy is more of an issue. Strategic planning is difficult when you’re holding four planetary models in mind, and you sort of have to do that when you and other players are looking to score optimally. Effective play focusing only on your own planet is feasible though, in low competition environments, since the nature of the game means even a randomly created planet will likely qualify for a few animal species here and there.

We tentatively recommend Planet in our fluid intelligence category, but we don’t recommend it for those with memory impairments.

Emotional Accessibility

There’s no player versus player in Planet – the only competition is indirect, over tiles and animals. It can be annoying to lose a key tile because you were behind in the player order, and likewise frustrating to think that you lose out on an animal because someone unexpectedly has a better planet for claiming it. There is though no explicit targeting. There’s little ability for players to gang up on another without taking a massive risk with regards to their own planet. You can all try to deny ice terrain to the player with the ice planet, but in the process you’re not claiming the tiles that actively work towards your own goals.

Even poor play will often result in unexpected animals coming to your planet giving the nature of the selection criteria. That’s good, but on the other side of that coin is something less good. Your beautiful planet-spanning Savannah might be impossible for anyone to beat, but it won’t do you any good in many circumstances if it doesn’t, or if it does, connect to all the other terrain types. With that in mind, players often gain, and lose out, in surprising ways.

As a result of this, score disparities tend to be quite small since performance has a kind of ‘reversion to competent’ forgiveness built into it. Scores in my experience tend to fall within a small window of points.

We’ll recommend Planet in this category.

Physical Accessibility

Technically you don’t need to hold the planet to play but it needs regularly rotated to find good candidates for available tiles and also to find where a planet satisfies the conditions for claiming animals. It’s a game that is fully playable with verbalisation, although not conveniently. There are no ways to easily reference tiles or planet core segments but there are relatively few possibilities in any circumstances. In any case, you can simply lay them out in an order when selecting. ‘Give me the third tile’

That becomes more of a problem when it becomes time to add that tile to a planet, because location and orientation matters. Imagine trying to tell someone how to rotate a d12 so a particular number is top. That’s what it is to identify a location for a tile in Planet. Rotation is then handled either descriptively ‘Place the ice so it intersects with the ice north of it’ or through exhaustive iteration followed by a ‘stop’. Similarly with scoring – someone can easily score a planet that belongs to someone else.

You could simply some of this by using a marker on the magnets fitted to the core to give them co-ordinates, but generally I’m not a fan of someone having to sacrifice resale value for accessibility.

But!

Problematically here, all of the decisions about where to put something depend on understanding the implications in context – how every tile connects to every other tile. The act of placement is massively aided by being able to rotate and analyse the planet during idle moments of play. I maintain too that the tactility of Planet is a big feature of how satisfying it is and you’d lose that if someone was manipulating the planet on your behalf.

If not playing with verbalisation, holding and rotating the planet can be awkward. Placing tiles requires some, although not excessive, precision. Removing tiles can be a little problematic because the production quality of the magnets is not great – I have seen them come loose (and free) several times. Replacements are provided, but it’s possible to peel away both the printing of the tiles and the magnet attaching the tile to the core.

With that in mind, we don’t recommend Planet in this category. It’s playable, but maybe not as much fun as it should be if you can’t hold the whole world in your hands.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

None of the art in the game is gendered. Well. Actually it’s full of animals and I assume they have a gender but I don’t know enough to say what it is. I honestly couldn’t tell a male tiger from a female tiger. Or a male otter from a female one. I’m a city boy. The first time I saw a horse when when I was twenty two years old, and even that was on television. Probably best not to rely too much on my judgement here. I guess if you really, really wanted to you could maybe investigate and find fault in the gender split of the animals but I think you’d need to really want it. When we talk about representation in these sections, it’s mostly about players being able to see ‘people like me’ reflected in the art of the game. That is, in most scenarios, not going to be relevant here.

The manual doesn’t default to masculinity, referencing ‘the player’ throughout.

Interestingly, everyone I have showed this to has said some variation of ‘Oh, I bet that one was expensive’, and I keep saying ‘Actually, no – it’s a lot cheaper than many of the games we’ve played’. I picked it up for a touch under £26 and given the innovation in the components I think that’s a bargain. It supports a maximum of four players, but importantly it supports those players beautifully – it doesn’t take long for anyone to get to grips with the rules. As discussed though, actually parsing a planet for scoring is a little trickier so it’s not a perfect introductory game for reluctant game-playing relatives.

We’ll strongly recommend Planet in this category.

Communication

There’s no formal need for communication during play, and no need for literacy.

We strongly recommend Planet in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

We don’t recommend Planet for those with visual impairments, but for those with minor vision issues it’s probably safe to relax that judgement. The problem there would be if a player is also colour blind, because colour is already somewhat difficult to make out at a distance and the ways in which tiles are distinguished otherwise depends on good vision.

There’s an unusual intersection here too, and that’s fluid intelligence and physical inaccessibility. Now, both of these categories are already a problem but I want to bring it up anyway because it’s interesting. Part of understanding the way your planet fits together comes in the idle analysis you do between turns, and when performing the scoring. That’s where you get to see opportunities in context. If someone is handling both of those things for you, it becomes harder to make meaningful decisions because you’re disconnected from the intricacies of placement. You become alienated from the product of your labour. It’s not an issue that really makes a difference since we already advise players with physical accessibility issues to play other games. It’s just something I noticed.

Planet plays reasonably briskly, and it cleanly supports players dropping out since there are no compensations required for lower player counts. Just stop playing and as long as there’s a minimum of two left the game can be carried on to the end with no changes.

Conclusion

It’s a little disappointing, although not surprising, that a game with such an innovative user interface would suffer somewhat in the accessibility analysis. That’s almost always the case when something new is done – it takes things a while for accessibility to catch up. Accessibility in VR and AR for example is under-explored in comparison to accessibility in other domains of usability. I’d like these to progress in lockstep but I don’t get to decide that. A lot of things would be different around here if I were in charge.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | C |

| Visual Accessibility | D |

| Fluid Intelligence | C |

| Memory | D |

| Physical Accessibility | D |

| Emotional Accessibility | B |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | A |

| Communication | A |

And there’s certainly scope here for Planet to do better in a second edition. I think the simplest, and biggest, fix would be to lower the cognitive costs by permitting players to track hexes they’ve counted. Just a little slot and pin arrangement, available for optional use, would go a long way to addressing a lot of the criticisms raised here. More distinctive colours. Maybe let you mount it on a globe rack and spin it. I guess that last one isn’t really feasible. There are a lot of things that could be done here though to improve the accessibility.

We review the game as it comes out of the box though, not the game as it could be. As it is, Planet is a good game (three and a half stars, baby) but it has numerous accessibility problems that mean while it’s a great gateway game (urgh) it’s mostly servicing an abled audience. That said, I’m very interested to check out the next Blue Orange game when it comes along with its inevitable future experimentation in the user interface of cardboard computers.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.