Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Mysterium (2015) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.90] |

| BGG Rank | 394 [7.22] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 2-7 (3-7) |

| Designer(s) | Oleksandr Nevskiy and Oleg Sidorenko |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

(yes, I went out of my way to import this because at the time it was unavailable in the UK)

Introduction

As much as I like Mysterium, and I genuinely do, it’s often hard to justify the extra set-up time over a game of Dixit. In fact, if you have Mysterium you have Dixit too – everything you need to play a serviceable game of Dixit is to be found in the Mysterium box. The cards you get with this title give it a far creepier vibe, but that’s not a bad thing. We gave Mysterium three and a half stars, noting that all its mechanics do is make it a less instantly satisfying experience than Dixit. There’s certainly a lot to like in the box though – if you wanted to commune with the afterlife, would you be able? Knock once for no, and twice for yes.

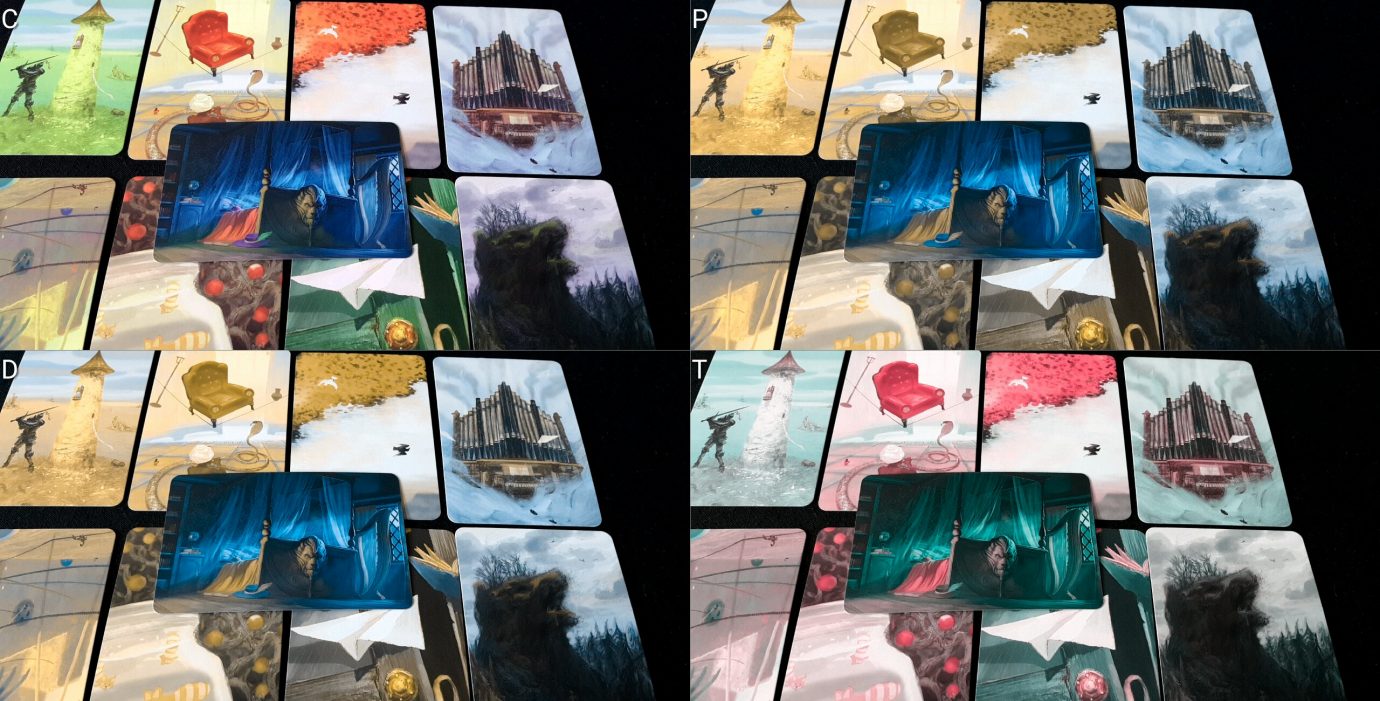

Colour Blindness

The colour blindness issues in Mysterium are similarly to those in Dixit, certainly when it comes to the vision cards. We also have colour blindness issues when tracking progress on the overall séance but that isn’t a serious barrier to play – you know what it is that you guessed correctly in the last hour, and the séance track is not a scoring track. It’s rarely very important that you know which players specifically are ahead of you in any element of the game.

When you’ve got them by the balls…

The vision cards though… well. Mysterium is a game about achieving a kind of common accord through the use of shapes, places, symbolism, colour and tone. None of the cards map cleanly on to any of the clues. All of them map imperfectly onto all of the clues with the affinity between the two being heavily modified by the social context of the group. It means in-jokes, cultural references, and shared vocabulary can be leveraged to build understanding. That falls down though when players at the table are colour blind.

‘I don’t know about you, but death has made me quite melancholy’

Not only are full channels of information distorted, they’re also potentially misaligned between individual players. While the imagery remains the same, the emotional impact may be different. The vibrant green of the top left card might become a melancholy yellow. Art is more than just colours and shapes of course – it’s the symbiotic relationship between those that create an emotional resonance. Mysterium is a game all about resonance.

Even leaving aside this nebulous, airy-fairy comment there are real, nuts and bolts reasons as to why it’s a problem. Let’s say we have a colour blind player attempting to map these cards to this clue:

Crying in the streets, but a lion in the sheets

Lacking any obvious symbolic connection, the ghost goes for communicating the colour of the bed-spread. They play out their clue to the investigator:

What? WHAT? Why is everyone so annoyed?

For those with Protanopia or Deuteronopia, the green of the vision and the red of the bedspread are the same. For everyone else, not so much.

I appreciate that someone with colour blindness is less likely to rely on the consistency of colour between themselves and the ghost, and vice versa. However, it’s also the case that those without colour blindness often lack an intuitive understanding of how it manifests itself. It’s entirely possible that a ghost without colour blindness will provide colour sensitive cards to a psychic with colour blindness. Considerate, careful play will avoid this but that’s a lot to ask of a game where you’re constantly looking for any relationship between visions and clues. Especially where the well-meaning observations of your colleagues may focus upon those as a major element of play even when that wasn’t intended.

Technically, all the cards are distinct and certainly the box is ticked for ‘colour blind accessible’ if we consider it only from the perspective of unambiguous identification of game elements. More properly though we need to consider whether colour blindness impacts on key elements of game information, and I think it does here.

It’s certainly playable if you have colour blindness, but only with considerable care and communal appreciation of the additional difficulty. As such, we don’t recommend.

Visual Accessibility

Visual accessibility is also a problem, and it’s a problem in the same way as it is in Dixit. The relationship between your card and the clues can potentially be anything. They might be symbolic, iconographic, metaphoric, or based on subtle interrelationship between visual elements. Consider our solution cards from the review:

Seriously, read the Discworld books. They’re marvelous.

Those were played by the ghost to indicate this set of clues:

Sister Morphine.

The pillows represent the bed. The dark eyes in the shadows represents the evil spirits against which the church is supposed to be a shield. The world carrying elephant represents the Discworld (one of my favourite novel series) and the typewriter. However…

One ghost, many probable murders

Perhaps the pillow (marked as it is with arrows) represents the doctor and anesthesiology? Perhaps the arrows represent the syringe. Perhaps the turtle of enormous girth (upon his shell, he holds the Earth, may it do ya well) represents the psychological weight of the job. Perhaps the terror in the darkness represents the spooky porch looking out onto the mist within which anything can reside. Or maybe the pillow card is a colour match, representing the location. Perhaps the purple of the attic floor is for the purple background of the syringe case. Perhaps the world on the back of the elephant is supposed to be the approximate shape of the Doctor’s bag.

We could follow the same second-guessing game for each combination of clues, but what I’m trying to do is illustrate the way the game works. Anything could refer to anything and sometimes what you’re looking for is a tiny connection that needs you to be aware of all the possible connections across all the possible cards.

That’s if you’re a psychic.

If you’re the ghost, you need to consult your screen of smaller versions of the cards, trying to pick out clues that are present that match the seven vision cards you have available. You’ll have an even harder job there, trying to find the optimal match between seven visions and as many as six clues (if playing with a full complement).

It’s a lot of visual parsing, regardless of on what side of the screen you reside, and it’s visual parsing that often requires an appreciation of the bigger picture. Each clue can be associated with only one player, so if there is a clue that works well for two cards you need to be broadly aware of what other cards may be a better fit. That’s especially true if you’re playing with the clairvoyance rules.

When playing in games of three or more players, psychics will at least be able to discuss the relationship between cards. That offers an opportunity for players to pool knowledge in a way that is independent of visual information. However, it’s also a game usually played with a timer (the game provides an egg-timer in the box), and with a final voting phase that prohibits discussion. You can house rule both of those things away, but at a cost of game flow.

As such, we strongly recommend you avoid Mysterium if visual impairments are an issue.

Cognitive Accessibility

Here, all the mechanical cruft works against the accessibility of Mysterium in a category where Dixit shone. The additional complexity introduced by things like the clairvoyance track and voting means that multiple decisions need to be taken into account when interpreting images. Similarly too, if you want to play well and make use of the clairvoyance system to maximise the cards you receive in the final vision, you need to be comparing X visions against (usually) X+2 clues. You don’t just say ‘I think this clue best matches this phrase’. There’s a lot more going on.

Similarly too, where Dixit offers self-selecting complexity Mysterium has a more restrictive, and more cognitively expensive, routine for the ghost. You don’t just let yourself express a phrase meaningful to you – you need to portion out your limited cards between multiple psychics, in a way that is ideally as unambiguous as possible. You don’t want to give one player a vision that would be ideal for another, and vice versa. Bear in mind each psychic has a unique clue to select – if you provide clues to a psychic that are optimal for another, they’ll be less inclined to pick the right answer because of this uniqueness.

When psychics fail their guesses, the game becomes even more cognitively expensive because the ghost now has to be offering visions across two or even three categories of clues – some clues might be suspects, some might be locations, some might be weapons. And here’s the kicker – those clues must be considered in light of previous clues for that category. You are in many respects telling a story with multiple vision cards, and since you can’t say ‘let’s start again’ your second card is going to be interpreted in light of the first card. So not only do you need to know what cards you’ve played previously, you also need to consider how they might be interpreted as a set.

None of this is to say that the game state itself is complex, because it isn’t – just that it has compounding difficulty based on the sheer number of moving parts. The more players, the more moving parts there are. The only place that you could genuinely say the game is cognitively demanding in any individual section is in the cumbersome setup.

In the best traditions of Holmesian investigation too, card play may involve a considerable degree of general knowledge as a simple consequence of symbolism. There may be literary allusions, popular culture references, assumption of geographic familiarity and more. The relationship between cards as expressed by properties of the laws of physics might be important, or in terms of the material properties of internal artistic components. In the review for example we talked about using the grim, dark sea as a clue for Scotland. That requires at least some geographical knowledge in a world where many people don’t know the difference between Scotland and Ireland. Or Scotland and England. Or Great Britain and Ireland. The Discworld reference would have probably been instantly tractable to anyone in my immediate social group, but not everyone has read those books. It’s always going to be difficult to find a happy medium between ‘what we know’ and ‘what we think they know’, and it is common to over-estimate familiarity with those things we ourselves are most familiar.

Often in these sections we discuss ‘accessible variants’, but I’m not going to do that for Mysterium. It has a perfectly good accessible variant already – it’s Dixit. If you want Dixit with an edge, play Dixit with the Mysterium cards. Mysterium itself though is something we can’t offer a recommendation for in either cognitive category.

Emotiveness

Mysterium once again suffers in an accessibility category within which Dixit thrived. Luckily, it’s through a rule element that is only present in some versions of the game, and easily ignored. It’s to do with the clairvoyance system and that final, silent vote.

Co-operative games tend to do well in this category because they eliminate several key emotional triggers – score differentials, ganging up, runaway leaders, and other issues in that category. They turn winning and losing into a shared experience – you all win, or you all lose, and it’s usually extremely difficult to identify a particular proximal cause for the outcome. There’s rarely one reason why it happened, and it’s rarely one person to blame.

Mysterium obeys that collegiate approach to co-op games until the last round, where the weakest players must vote with the least evidence. A straw poll is taken of votes, and then counted out – if there is not a majority of votes for the correct culprit, everyone loses.

Wow, this does a lot to undermine the co-operative feel. First of all, it places the most likelihood of failure onto those investigators that have had least success in the game. It’s like someone doing poorly in a class and then being given the advanced placement exam. You are genuinely set up to fail because you’re forced to vote with the least information. Then, it creates a bifurcating situation where psychics can vote for different culprits. Suddenly, it’s not only possible for individuals to be correct, it’s possible to identify which is which. Nobody has to own up to an incorrect guess, but the ghost will know (paper envelopes are indicated by psychic), and by a simple process of elimination it can be worked out. And then, this ties collaborative success into individual voting. You as as a single psychic could get it right and still lose the game.

All of these contain circulars

If emotional accessibility is an issue, we recommend playing without the straw poll at the end. We’ll tentatively recommend Mysterium in this category, but this is something to bear in mind.

Physical Accessibility

The game state tends to sprawl quite significantly, reaching from one side of a decent sized table to the other. This is a consequence of the path the psychics must take, and the number of options involved in this. There are ways you can limit the spread, such as by phased revelations of the cards and clearing away completed layers of the séance as they’re finished

Some of this sprawl too is down to the irregular sized components – locations and suspects all have large, tarot sized cards. Weapons have tiny, quarter poker-sized cards. The ghost has their own deck of cards behind the screen that they need to hunt through to find the matching elements from the séance. That adds a lot of physical manipulation onto the ghost, and the nature of the game puzzle means that a player involved in the psychic part of play can’t realistically help very much. Even if the cards are selected by another player, they need to be slotted by the ghost into the plastic sleeves fitted to the back of the screen. While it’s not especially difficult to do in and of itself it must be done in secret. Any leaked information there will dramatically alter the course of the séance.

The ghost has the most physically intensive role in the game, being responsible for drawing vision cards every hour, distributing them to individual players, and knocking out assent and dissent as to choices. The knocking part of course isn’t strictly necessary – a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or really any kind of signal would be perfectly effective as an alternative. I’m not even sure the knocking is mentioned in the rules, but it is so thematically perfect that I feel the game loses something by its absence.

For psychics, physicality of play is primarily in accepting the cards they are given (which are not secret) and moving their psychic token up through the game board.

Things can only get better

If playing with clairvoyance, there’s a bit more involved – distributing agreement or disagreement tokens during the guessing period for each psychic, and moving the corresponding clairvoyance token up the track to indicate success and failure. There’s also a final voting phase in which a voting token is placed in a paper envelope, but the envelope is roomy and the token is quite substantial so it is not in and of itself notably inaccessible. It’s also numbered on one side and shows a question mark on the other – it’s possible for someone to handle this phase on behalf of any other player without necessarily revealing their vote in advance.

Otherwise, the largest physical burden is in examining the cards – there’s no reason they can’t be moved or played in a way that is comfortable for the majority of players. Using as it does non-contiguous game state gives considerable flexibility for comfortable setup.

We’re prepared, with caveats, to recommend Mysterium in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

The theme is one heavily imbued with the occult and the paranormal, and this might be a problem for certain groups. Religious parents for example may be uncomfortable with the concept of a séance, and the heavily thematic elements of game-play mean that you can’t really avoid its presence. It’s not really a scary game, although if played with the right amount of pantomime it can certainly be dialed up into spooky without any real effort. A decently creepy soundtrack and flickering candles will add a lot of ambiance to play. The age range on the box is 10+, and that’s probably in the right ballpark. You wouldn’t necessarily want to play this with young children.

The psychics represented in the game have a 50/50 split between men and women, and even show a few non-western faces in there. Six investigators doesn’t give a whole lot of room for diversity, but they’re doing okay.

The suspects have a split that is skewed towards men, and they’re all white. Now, I’m not sure what I think about this from an accessibility perspective – I don’t know to what extent it’s important that people can see themselves represented as explicit suspects, and it’s always going to be risky to exercise diversity when it comes to labelling people as villains. Having said that, it’s also questionable to have all the murder suspects be white. Perhaps it’s not possible to come to an arrangement here that makes everyone happy. Similarly, statistics tell us that most violent crime is committed by men (by a pretty significant margin). Also, since the suspects are all either in the employ or strongly associated with a particular region, and since the game would be different if an alternate theme or locale were employed, I don’t have any real problems with this. As ever I advise you to make up your own minds. It seems okay to me, although I appreciate these issues are nuanced.

Coupled to this, there’s no explicit sexualisation or even particularly any sensualisation. Suspects range from old withered men to young, serious women. It runs a gamut of body types too. That’s nice, although the explicit default to masculinity in the manual is less so.

With an RRP of £40, it’s a little pricey. It does though support two players (with one player acting as the ghost and the other as the investigator, or investigators), and scales all the way up to seven. While the theme may not be suitable for very young children, it is otherwise very flexible when dealing with the numbers that allow for ‘family game night’. It doesn’t work especially well as a two player game though, although it does work reasonably well for all other player counts. Larger player counts are probably best, which is reflected in the distribution of recommendations on Boardgame Geek.

We’ll offer a strong recommendation for Mysterium in this category, with a little negative mark for the unnecessary gendering in the manual.

Communication

While most of the game consists of interpretation and indication of selection, there is a general assumption in collaborative games that communication will be involved. Investigators are encouraged to pool experience and understanding as they work to identify the correct clues, and then as part of the clairvoyance step there’s a degree of to and fro as people explain (or not) their reasons for the votes they make.

It’s not strictly speaking necessary, but it is expected and the nuance of communication will be considerable. Issues of tonality, intention, symbolism and interpretation are all fair game when it comes to visions, and articulating why a card may make someone think or feel a particular way can be complex. This is especially true when the intention behind a vision may be to evoke a contingent memory, or as elucidation of an abstract relationship.

The game comes with an egg-timer used to ensure conversation stays within a reasonable time limit, but as is usually the case this kind of thing is not ideal when aiming to ensure accessibility. It is probably best to come to a more flexible arrangement regarding turn duration.

We’ll offer a tentative recommendation here – the expected level of communication over Dixit is substantially higher, even if the nature of the communication and interpretation that goes into play is roughly comparable.

Intersectional Accessibility

There is an unusual issue here when it comes to playing with colour blindness and the intersection of cognitive accessibility. If trying to match cards to players, and trying to be sensitive to the issues of association caused by colour blindness, it creates a considerable additional cognitive burden on play. This is mostly when playing as the ghost, but it’s also something that has to be taken into account by everyone around the table – conditionally ignoring particular cues when they are played to particular players is expensive.

While there are no hidden hands for psychics, there is a lot of hidden information if you are the ghost. The good news is the screen itself handles most of this elegantly – no need for separate card holders because all the pertinent solutions are in front of you and the screen hides your face up hand as well. The bad news is that there is almost no way to ask a psychic for help with your hand in a way that doesn’t leak game information. That’s an issue particularly for the intersection of visual and cognitive accessibility, but also occasionally physical accessibility. If you are left unsure as to what a visual element means, or whether it’s one thing or another thing, you can’t ask and you can’t show without revealing more than would be intended.

There is an asymmetrical dependency on players within the game. It’s relatively easy to deal with a psychic dropping out – someone else can play for them, or they can just be quietly removed from play and the game can move into one of its smaller player count rules. There is no way for the ghost to drop out though without severely impacting on the game. Someone else can sub in, but certainly for those players that have already received and failed to interpret clues there may be a discontinuity of symbolism that removes the links between future and past guesses. To be fair, over time this solves itself because a process of elimination means eventually everyone will get the right answer. Within the strict time limit of the séance though, there are only seven turns. Replacing a ghost mid-game may require some fudging, although it’s certainly possible.

Leaving aside the relatively long setup time, Mysterium doesn’t take a long time to play. Assuming seven full turns, and assuming that the timer isn’t used but a reasonable ‘now decide’ limit is placed on play you’d be unlikely to spend more than an hour poring over the clues and solving the final puzzle. The setup time though does disproportionately impact upon the ghost – they’re the ones that have to search through the decks for all the key cards, and make sure they’re properly associated with the various quest elements. With practise, this becomes relatively easy to do – perhaps five minutes or so – but for those unfamiliar with the process or having to do this whilst taking accessibility considerations into account it may be longer. Game length then is not likely to be sufficiently onerous to exacerbate issues of discomfort, but the game length for the ghost (and indeed, the intensity of the experience) is a more significant consideration.

Given the way the ghost must interpret, associate and allocate cards to investigators there is sometimes a fair amount of waiting around for the psychics. Cards are dealt out in whatever order the ghost likes, and the last psychic may find themselves with nothing to do with regards to their own progress for a few minutes. Rushing the ghost doesn’t help either – good clues require thought and consideration. All you’d get from a hasty ghost is a hasty clue. As such, it might be difficult to keep attention focused on play. Mysterium is a game of ‘hurry up and wait’.

Conclusion

We say this regularly on Meeple Like Us – just because two games share a lot of similarity, it doesn’t mean they’re going to come out the same in the teardown. Accessibility is such a nuanced, tightly coupled topic that even small changes in design can result in big changes in the grades.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | D- |

| Visual Accessibility | E |

| Fluid Intelligence | D |

| Memory | D+ |

| Physical Accessibility | B- |

| Emotional Accessibility | C |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | A- |

| Communication | C |

As you can see, there aren’t many categories in which Mysterium gets off unbloodied. It’s a bit like the murder victim in the game itself in that respect. Where Dixit’s ease of play and levity create accessibility, Mysterium’s ponderous ludic architecture takes it away.

As we discussed in the review, we believe Mysterium is a better game than Dixit. However, it’s also a harder sell, and the extent to which it improves on the formula is offset to a degree by its extra complexity. However, if you want that beautifully implemented theme, Mysterium delivers ambiance in spades. That, in and of itself, may make it worth the purchase.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.