Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Mechs vs. Minions (2016) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [2.44] |

| BGG Rank | 72 [7.97] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Chris Cantrell, Rick Ernst, Stone Librande, Prashant Saraswat and Nathan Tiras |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

If you broke Mechs vs Minions in two you’d have equally weighted chunks of what seem like high quality game. You’d expect if you brought them back together you’d get a kind of Fun Fusion that generated energy from the critical mass. You’d be wrong though – Mechs vs Minions is a game at war with the two angels of its own better nature. The result is an unsatisfying alchemical blend that doesn’t turn what it touches into gold. It just bubbles aggressively for a few moments before converting its reactive mass into a largely inoffensive slurry.

We gave it three stars in our review. It’s basically okay.

Let’s take a look at its accessibility profile and see if there are some positive things we can extract from the box. I’ve loaded up my console with ramble cards. Let’s see where they take us.

Colour Blindness

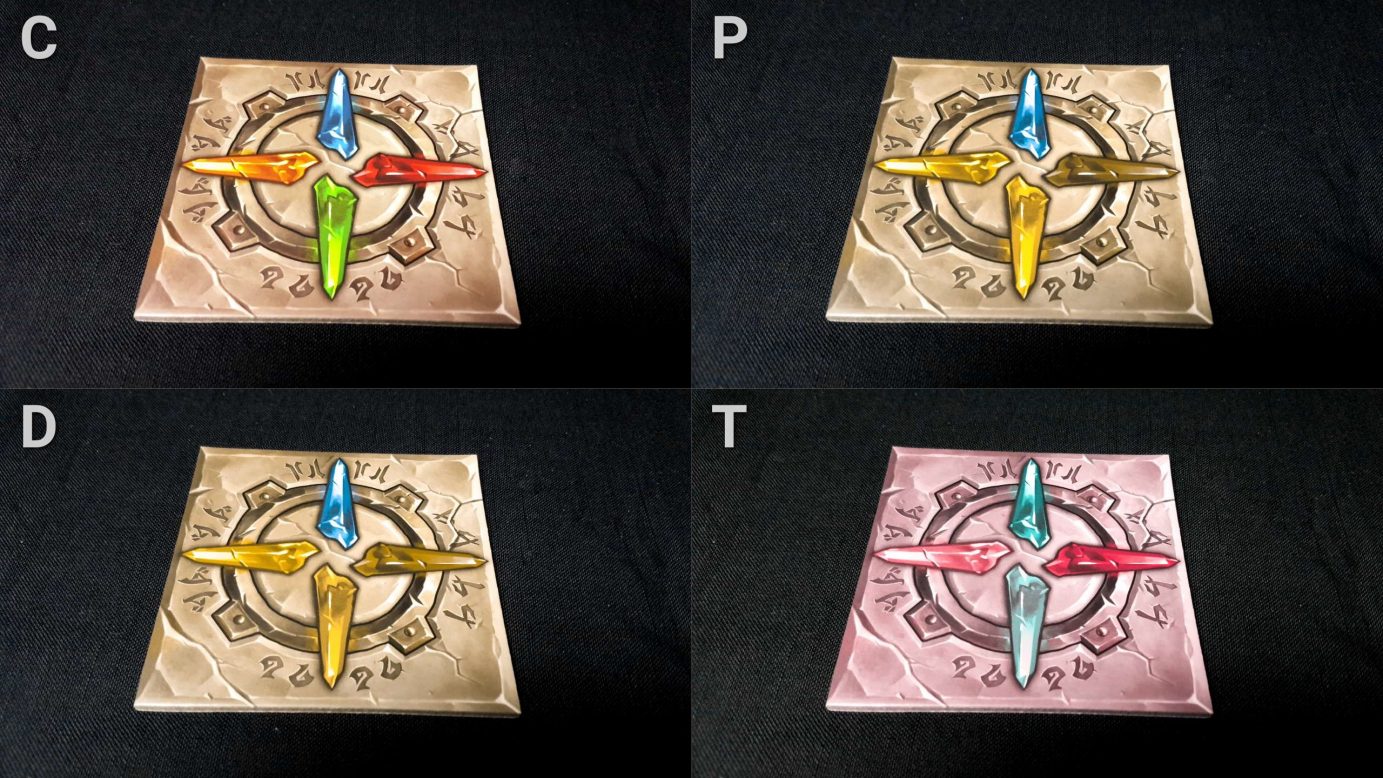

The four coloured runes present on the board have their own symbols, although these aren’t as distinctive as I’d like. Consider red versus yellow and the importance the orientation of the board have on their identifiability.

That matters, because these symbols are replicated on the dice you roll to energise them. They’re still unique, just… a little bit less clear than they perhaps could be.

The compass marker you get doesn’t have a particularly easy way of converting runes to colours. The ‘inscriptions’ around the edges act as kind of indicator for the runes but this is a lot less accessible than simply indicating them on the markers themselves.

This is a relatively minor issue, and it will get easier to deal with with practice. The rest of the game does not use colour as a primary channel of information although certain scenarios do have an annoying habit of referencing map tiles by named colours. Your mechs are all distinct, the minions are uniformly grey, and the cards that are employed to program your deck are sufficiently distinctive even without their colour coding.

We’ll strongly recommend Mechs vs Minions in this category.

Visual Accessibility

A lot of the board state can be ascertained by touch, but not all of it. A totally blind player would be able to tell where the mechs were (and who owned them) and the presence of minions, crystals, bombs, the school entrance and a few other things. There’s quite a lot of tactile information presented on the board, although special features such as runes, oil slicks, the presence of lava and so don’t have a distinct feel. Since the configuration of the board changes with each scenario this is something of a problem – even though you’ll grind over each board a number of times the orientation and specific meaning will change with context.

The game does make use of standard D6s, but also D12s that use encoded colours to control everything from minion movement to area activation. Standard dice, with a lookup table, could be used to compensate for this. Some elements of play are real-time, although realistically there’s no reason players should take that overly seriously.

More problematic though is that the core of the game is trying to get your console to do something useful, and that involves examining the board in minute detail to work out the implications of every change you can make. Players will have a maximum of six ‘effects’ on their board at a time, and each of these will have one of three levels. There aren’t so many cards in the game that I think it would be impossible for someone to memorise each and their impact at different levels – the progression is reasonably straightforward. It would be an additional memory burden to hold the current layout of a console in mind but not an infeasible one.

However…

Knowing what your board does now is only part of the puzzle. What matters more is how you can change it from the draft of cards available. Depending on how many memory cores are active you may be choosing between one and seven cards for your console, and each card will have a scrap effect that either repairs damage or allows you to swap undamaged slots of your board. Cards can either power-up other cards (if they are of a compatible category) or overwrite them. From this you need to work out what’s best for the game state in front of you.

Consider the console shown above. The memory core never does any active harm and it does a lot of good. But the speed card always requires you to move, as does the Omnistomp. Given the role that you’re looking to fulfill this round do you want to swap those around? Or do you want to grab an electricity power card and replace speed with damage? Or perhaps you want to overwrite Omnistomp with a second speed card that permits you to clear away all the minions leading up to the portal into which the bomb is supposed to go. Two speeds would take you to the point your chain lightning would have a useful effect too, as would your skewer. Or perhaps you’d like to consider what your options would become if you rotate towards the left with your memory core. Or the right. Or back the way you came. What happens if you swap speed for Cyclotron through a scrapped card? What if you swapped Omnistomp for Memory Core? What is the combination you can eke out of the console and the draft that works best for this specific setup?

Maybe none of them work. Maybe you need to consider what you’re setting yourself up for in the round after this one.

Changing one thing in your console may have dramatic effects on what your mech actually does, and that’s going to involve considering not just the board as it is but the board as it would be with every single change. That’s primarily a cognitive cost (and will come up as such in our cognitive accessibility section). However it’s one that becomes exponentially more difficult if you must hold in mind a model of the game and your console and its current composition and all its potential future configurations and their impact on the board.

That said, I’m overstating how tactical the game tends to be because really what you’re looking to do is get closest to effectiveness rather than actually find the solution to the puzzle. There often isn’t one. If players are happy with enjoying the sheer mayhem of play a lot of this becomes more feasible but at the same time you lose a very substantive fraction of what Mechs vs Minions is supposed to be.

For those with less severe visual impairments, the cards are (mostly) well contrasted and consistent in their design. The different categories of cards have icons that are often poorly blended into their background art but the palette used for each is distinctive. Fire cards are red, electricity cards are yellow, mechanical card are blue and computer cards are green. As such even if the icon may be obscured the image is (usually) enough to differentiate. Cards are reasonably information dense but also well structured – the information needed will always be in the same place. The only other issue with the cards is that the grids that are used to indicate area of effect may be difficult to make out and especially hard to do so when they have differing areas of effect at different power levels.

We don’t recommend Mechs vs Minions in this category, but it may still be suitable. That depends on the flexibility of everyone at the table with regards to whether achieving the goals of the scenario are critical to having fun.

Cognitive Accessibility

There is a certain amount of fun to be had in just slotting cards into the console and seeing what happens, but that’s a very shallow form of what Mechs vs Minions is supposed to be. The design intentions make it a massively problematic game in this category.

The flow of play is reasonably reliable in that it follows a fixed structure of draft, program and execute followed by minion and scenario activities. Those latter two change depending on the mission. For example, in mission one minions spawn on unoccupied rune squares. In scenario two they spawn at the edge of map tiles and move in a fixed pattern. Sometimes they’ll move twice. The movement rules in each scenario are straightforward but require the enacting of a set of fixed priority orders when dealing with obstacles.

The game gets more complicated as time goes by though, and there’s a point where all the little rules start to become cognitively taxing to parse correctly – especially given the ambiguity of many of the specialist edge cases. The manual is not fully comprehensive.

That’s not the real problem at the heart of Mechs vs Minions though. The problem is that doing something worthwhile is incredibly cognitively complex. I have spent solid minutes locked in contemplation, evaluating what I can accomplish from the options I have. This is an act of assessing branching possibilities that stem from your console and if you’re going to be comprehensive about it there’s a lot going on:

- What card should I take from the draft, taking into account what my fellow players may want to do.

- Do I want to slot that card or scrap it?

- If I want to scrap it, what damage do I want to repair or what two slots do I want to swap?

- If I want to slot the card, where do I want to slot it?

- Where would I want to slot it if I exercise my options with the other cards?

- How would slotting it in a particular location alter the way I’d want to exercise my options in the other cards before and after?

- Do I want to overwrite an existing card with the new one?

- What are the implications of that?

- Do I want to power-up an existing card with the new one?

- What are the implications of that?

- If I execute on my current plan, what will it to do the minions?

- What will it do to other players?

- Where will it put me on the path to accomplishing the goal?

That’s before you take into account where you’ll be when the minions move on and what will happen in the next round, and the damage you might pick up as a result.

All of this you need to cross-reference against a board that may be in a dramatically different state when you get a chance to enact upon it. If you’re third player to go, you need to be considering what the other two players will do with regards to their consoles. You don’t need to calculate what’s best for them – that’s their job – but you do need to know what the board will look like when it gets around to you.

The sheer amount of memory and fluid intelligence processing required for this is massive, and if any level of tactical play is to be permitted you can’t do without it. It’s not even as simple as letting one player mess around while others do the real work. That messing around may push mechs and critical mission objectives around the board and that will interfere with everyone else.

And even that works on the assumption that all this thought is being invested to a productive end. Sometimes your goal is ‘move forward one space’ and you might find that impossible from what you have programmed into the console. Every decision you make has to come off of the momentum of the decisions you made earlier. Usually your goals are considerably more complex than simply getting somewhere or killing a minion.

We don’t at all recommend Mechs vs Minions in either of our categories of cognitive accessibility.

Emotional Accessibility

If players are goal oriented this is one of the most frustrating games I can imagine putting in front of them. It’s not that programming games are inherently at odds with being focused on accomplishment, it’s that they become so the more precisely co-ordinated everyone has to be to satisfy the game goals.

This is a co-operative game and normally that means everyone is on the same side. And nominally that’s true here of Mechs vs Minions but you’re all going to get in each other’s way. If you’re not mentally prepared for all your careful planning to be undermined by a misplaced nudge you really should avoid playing. Imagine a game where you’re slowly being overwhelmed by advancing minions and all you need to do is move one square forward, rotate and forward. Now imagine that your first movement card limits you to three at the minimum and your second forces you to move three spaces forward or to the sides. The cards you need often don’t show up when you need them in the draft and even if you get everything lined up perfectly one single minion may end up inflicting a damage card that completely ruins your carefully curated strategy.

That’s funny if you’re in the mood for it. If you want to actually achieve the scenario goals though it’s just frustrating. And those goals are difficult. Made more so by the fact that early mistakes tend to set the trajectory of your experience. This they do while being theoretically beneficial enough that you feel uneasy about sacrificing currently poor but upgraded cards for weaker but more situationally useful powers.

We don’t recommend Mechs vs Minions in this category.

Physical Accessibility

There is a lot of physical manipulation needed on the board, including moving potentially dozens of minions in fixed movement paths and often in dense knots of figurines. This may involve moving them in and out of crystals or across oil patches that carry their movement forward. Moving mechs is made simpler by the fact that they tower over the other pieces. When mechs kill minions, they should be collected up and put on the score board where they get cashed in five at a time for unlocking higher degrees of power in each of your mechs. That occasionally needs done several times in a turn. Various markers also go on that board and slightly upsetting a table can result in the doom and gear markers moving farther than you might like.

There’s a lot of physical manipulation required of the board in other words, but none of it need be actioned by any particular player. Most of what happens on the board is set in stone by the player console you have programmed and the slots are numbered so it’s easy to say something like ‘Give me card two and slot it into position five’. At that point players can verbalise the instructions for their mech, resolving decision points as necessary. The only problem there is that the console requires cards to be clearly shown so that the power of abilities is easily determined, and they are easy to dislodge as new cards are played in and out of slots. The console boards are large and unwieldy and can’t be passed easily between players. Play with verbal support is possible then, but not especially convenient. You need to go to the console rather than the console going to you, and leaning over to change a console may be difficult.

Nonetheless we’ll tentatively recommend Mechs vs Minions in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

The four Yordles provided in the game come with their own backstories and biographies available on the League of Legends wiki. I am sorry to say I now know more about these characters than I do about a number of significant living public figures. I don’t know how correct the wiki is, but it appears that Tristana is the only female Yordle and the other three are male. Whether that is likely to bother players is I guess up to them. It’s hard to say what the impact will be when you’re playing a mystical spirit in a Furry bodysuit. The manual does not default to masculinity and I have no idea what the gender of minions is supposed to be. I think they are genderless magical constructs but I don’t really want to delve into the parts of the internet where the details of minion genitals are most enthusiastically discussed.

Anyway, it would have been good to see a better gender diversity here.

In terms of socioeconomic considerations, $75 is a lot to spend on a board game but also in the frame of reference we need to use for hobbyist games it’s an absolute bargain. If this were to be produced by a hobbyist publisher I’d expect the price to be double, or more. In fact, I’d probably expect it to be the scandalously excessive $500 level of an aggressively overfunded Kickstarter. Players are absolutely not being overcharged for what they get here. Nonetheless… $75 would get you a multiple number of other games, and in an objective reckoning where your wallet doesn’t grow or shrink according to relative value I think it’s a lot of money to be asking.

If you decide to get it too availability of the game is erratic. It can be purchased directly from Riot Games on their website and gets sent out in a series of waves. Wave 3 was sent out in 2018 and I don’t know if/when Wave 4 will be sent out. I suspect there’s probably a threshold where number of pre-orders triggers a production run. It is not, as far as I am aware, easily available through conventional sales channels. A pre-order, if they even support that, would require money to be locked up for potentially a long time. The game tends to sell out very rapidly when new waves are released so it’s risky to wait to pay at a time when it’s available. Getting hold of Mechs vs MInions may involve paying a big chunk of money with no obvious indicator as to when it’ll result in your game being sent.

We can only tentatively recommend Mechs vs Minions in this category.

Communication

Scenarios come with a reasonably large amount of scenario text, new considerations and complexities and more. Cards contain precise instructions that must be enacted exactly, although the linguistic complexity associated is not high. Some degree of strategizing with other players is important, although it is unlikely to be especially predictive of overall success given the random chaos at the heart of the game. What strategy is required will be complicated by the non-standard vocabulary employed by the game in terms of card effects and game terminology.

We’ll tentatively recommend Mechs vs Minions in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

Aside from our recommendation in the colour blindness section, what grades that we offer for Mechs vs Minions are all tentative at best. We are especially critical in terms of cognitive accessibility and visual impairment. It’s probably fair to assume that intersections wall to wall are going to be sufficiently problematic to tip the balance into a recommendation to avoid. For example, colour blindness will make disambiguation more difficult for players with physical impairments or communication impairments. A physical impairment intersecting with a communication impairment would impact on ease of verbalisation. While that may not be a show-stopping problem it might add just enough extra overhead to make the game unplayable.

Mechs vs Minions plays reasonably briskly, sometimes. It’s possible to get into a groove where nothing productive is being done and yet you’re still managing to keep minions at bay. In those circumstances the worst aspects of the game come to the fore and frustration begins to mutate into boredom. What variety there is in play comes from opening the various scenario packets and without a regular injection of new material the whole experience becomes stale. Easily stale enough to cause attention problems as you grind through the same scenario. That leads into issues of discomfort and distress as players look to maximise the play-time to set-up and clean-up ratio. It’s a game that takes a lot of time to properly clear away and you’ll want to make sure you get the most out of the experience of taking it down from the shelf.

Conclusion

Well, Mechs vs Minions didn’t wow us as a game and it doesn’t wow us as an accessible product. Sometimes that’s the way it goes. At least it can console itself with the largely universal praise it has received elsewhere on the internet. I suspect it, and its designers, will find some way to move on with their lives.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | A- |

| Visual Accessibility | D |

| Fluid Intelligence | E |

| Memory | E |

| Physical Accessibility | C |

| Emotional Accessibility | D |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | C |

| Communication | C |

It’s surprising really that a game that offers you so few opportunities to really do what you want to do should be so cognitively inaccessible. The problem there is it perches right on the edge of agency. It feels like you can probably do what’s needed if you can just puzzle it out. There are so many axes of freedom in your console that a solution must be there. As such, you invest the effort only to find ‘Oh, no. There’s nothing I can do after all.’ It’s deceptive that way.

We gave Mechs vs Minions three stars in our review. A mediocre game made of better material than its design would imply. We don’t recommend it particularly as a game, and that might take the sting out of the fact that we can’t be too enthusiastic about its accessibility either. There are plenty of games that serve you better in both capacities.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.