| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Lords of Vegas (2010) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [2.34] |

| BGG Rank | 531 [7.35] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 2-4 (3-4) |

| Designer(s) | James Ernest and Mike Selinker |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to review a board game about being a gangster.

You think I’m funny? You think I’m here to amuse you? You… you don’t? Oh.

I’ll be honest though, I didn’t expect a theme as glitzy and glamorous as running chains of a high-stake casino in the mob-riddled Vegas strip would come in such a thoroughly underwhelming box. Look at that thing. That doesn’t scream ‘VEGAS BABY’. It whimpers ‘budget craps table in Barnsley’. It looks like the Lidl own-brand version of home roulette wheel. To be fair, the first few turns of the game take place in the grim, ‘parking lot with delusions of grandeur’ Vegas of the early 40s. If it’s going to become the hive of scum and villainy that we all know, it’s going to need us to make it happen. The grim aesthetic of the box is our starting canvas. The rest is up to us.

Just got into town about an hour ago.

I put off buying, and playing, Lords of Vegas for quite some time because I didn’t really believe anything fun could lie inside such an unappealing box. Sure, it’s got pictures of opulent casinos on the front but it also has a bald-headed thug obviously about to commit a racially charged hate-crime amidst the vapid backdrop of some unconvincingly rendered 3D dice. It just looks – boring, and as such I thought the game itself must be boring too.

I was of course wrong, because Lords of Vegas is fun. Lots of fun. It’s a game that not only obsoletes Monopoly in terms of gameplay, but also in terms of its ecological niche. It’s a game of buying property, earning money from that property, and trading cash for favours with the other people around the table. It’s a game of merciless competition and some of the most wonderfully effective ‘screw you’ mechanics I’ve seen in any game. This is a Vegas where fortunes are made on the roll of a die but your empire is built atop the buried bones of those that stood in your way. Your casinos are gentle, fragile flowers moistened by the tears of your competitors. Tears flow freely on the Vegas strip. We’ll have cause to shed them too.

The game doesn’t exactly go out of its way to entice those that have not already bought in to the premise. The Las Vegas of our board is unremittingly grim, consisting of empty parking lots, cheap flea markets, and a bar surrounded by what look very much like cultists in ill-fitting brown robes.

The mob isn’t the only way you can lose a kidney in Vegas

This is the sad and depressing stretch of desert we need to turn into diamond, and it’s not going to be easy. Each of us plays a budding Bugsy Siegel, with nothing in our pockets except for a dream, several million dollars, and a few presumptive locations upon which we can build our first casinos. I know it doesn’t sound like much, but you know what they say – a few million here, and few million there, and pretty soon it adds up into real money.

Our fortunes get set by the two cards we draw at the beginning of play – these determine which lots we own, and how much money we get. Some lots have greater potential than others, although they’ll cost more to develop. If we get the fuzzy end of the lollipop in terms of our initial lots, we’ll begin with a bit more cash to make up for it. Properties adjacent to the Strip are likely to be the most valuable, and their price reflects it.

Vegas, baby!

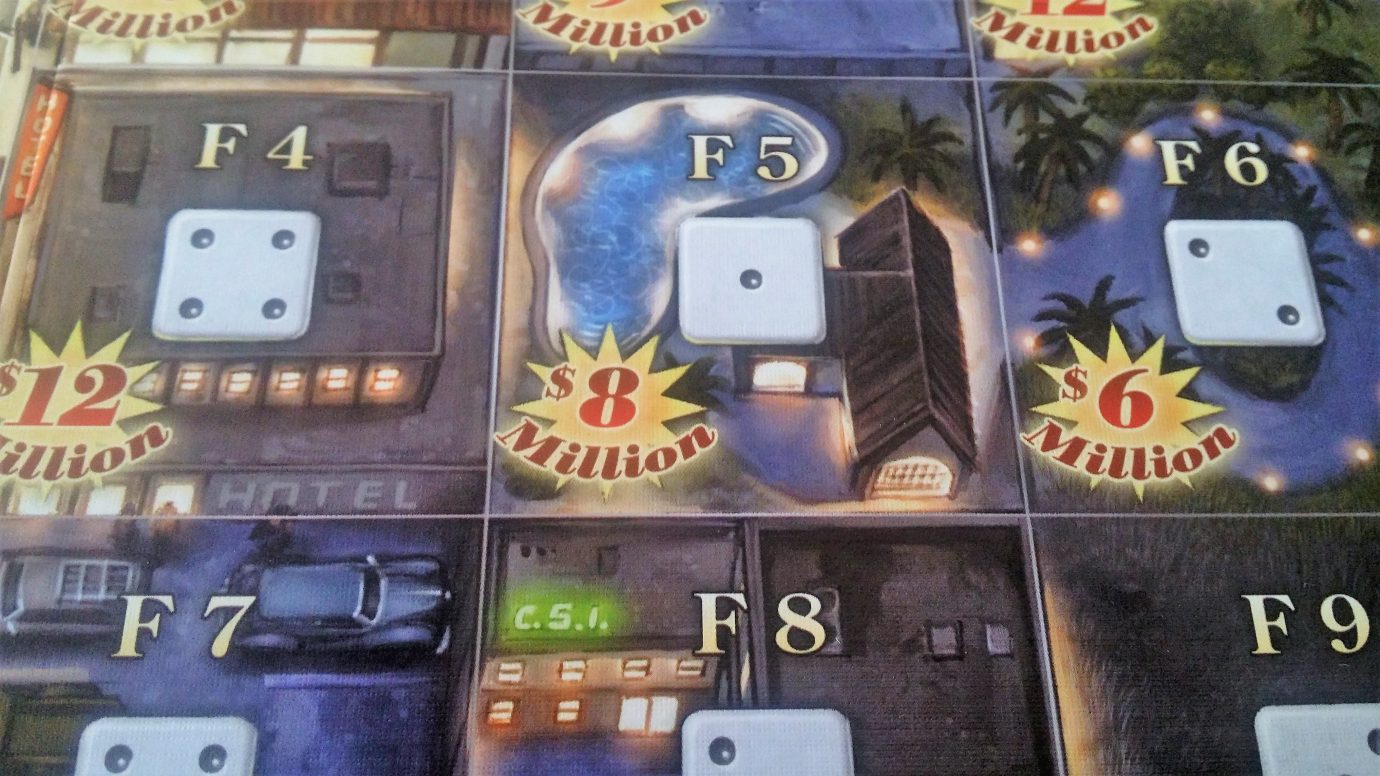

We also begin the game with a pile of lot tokens and casinos. If the casinos look like dice, that’s not your failing eyes sending you incorrect data – each of the dice we own is a building we can place onto a lot we have purchased.

This is your own personal Bellagio

The first two cards as shown above would give us a starting allowance of a cool ten million. Ten mill, as we say in Vegas. It also gives us the lots E3 and B1.

These are both strip adjacent properties, and so even our starting fortune isn’t enough for us to build anything. However, lots are valuable in and of themselves – each one will generate $1m of income per turn. It’s not much, but it soon adds up to a sizeable amount of free money. That’s good, because this is Vegas, baby! You can’t take a dump in this town without forking over a wad of cash. When you take a piss, nickels and dimes come out. It’s very, very sore.

Paper money. This is going to come up in the teardown.

Each player goes through this process, drawing a couple of cards and claiming their starting capital. But this is more than just a random setup – it doesn’t look like it, but the game has already begun.

The deck you get with Lords of Vegas is hefty, and includes a card for every lot in the city. Each lot is also associated with a casino. If the casino is drawn as part of regular play everyone that owns a casino of that type gets a pay-out. If you’ve been a canny casino operator, that pay-out might be substantial. But here’s the thing – every casino comes with an expiration date. At some point, and it might not even be in the game’s lifetime, a particular theme is just going to stop paying out. There will be no more cards of that kind left in the deck. It’ll be a flaccid, unprofitable monstrosity of faded glory and gaudy extravagance. Rather like my pe…

What’s hot? What’s not?

Every single time you draw a card you’re changing the economy of chance. A streak of success is great, if you’re on the receiving end. But that success is coming as a result of mortgaging your own future – that success isn’t going to last. Except, perhaps it will! In Vegas, unlike in real life, the dice absolutely do have memories and you can take advantage of that.

Over the long term, every casino is equally popular. In any given game though, that popularity comes in phases as they drop in and out of fashion. You never know if you’ve backed a donkey, because you never know quite where in the deck you’ll find this landmine:

Boom!

It’s going to be somewhere in the bottom 25% of the cards, because that’s how we handle its setup. Who knows what cards it’s blocking as it lurks beneath the surface – maybe silver casinos just aren’t going to come up very often this time around, because they sunk to the bottom of the deck like a snitch in cement shoes. Some themes pay out with an almost perverse sense of humour – you and your friends watch lucrative opportunities pass by again and again without profit. It’s tempting to take advantage of it. Maybe that theme is on a hot streak! Maybe the cards weren’t shuffled very well – maybe this is a sign of a clumpy distribution! But every card you draw reduces the chance that theme will pay out in the future, and casinos needs a lot of investment before they will earn your fortune. When is it too late to jump on a trend?

But then, what if a theme hasn’t paid out for ages? There’s a chance it’s not going to pay out again, but if it does… provided nobody else is investing in that potential, you might just clean up. No risk means no reward, right?

Once the setup has finished, turns have an agreeable rhythm to them. You draw a card, claim its named lot, and then all the matching casinos pay out. In the later stages of the game money circulates through the system with all the frictionless rapidity of a greased eel. You can’t hear yourselves think for the constant ‘cha-ching’ of the fruit machines. To begin with though, progress is slow, hard-fought, and frustrating. If you get lucky, things can be pretty great for you on the Strip. If you don’t, you’ll soon find yourself fading into irrelevance while everyone else makes it rain.

If you want a casino, and you own the lot, it couldn’t be simpler. Pay the money, pick a casino colour, and put one of your dice in it showing the correct number of pips:

Someone is getting their fingers broken in this casino

The size of your casino is determined by how many matching tiles there are in each contagious section. The size of a casino determines the points it generates, and only the boss of the casino gets these. The boss is the player that has the highest face value die in a particular casino. The profitability is determined by the pips on each die – that’s how many millions you get every time the casino pays out. Everyone gets cash, only the boss gets the prestige.

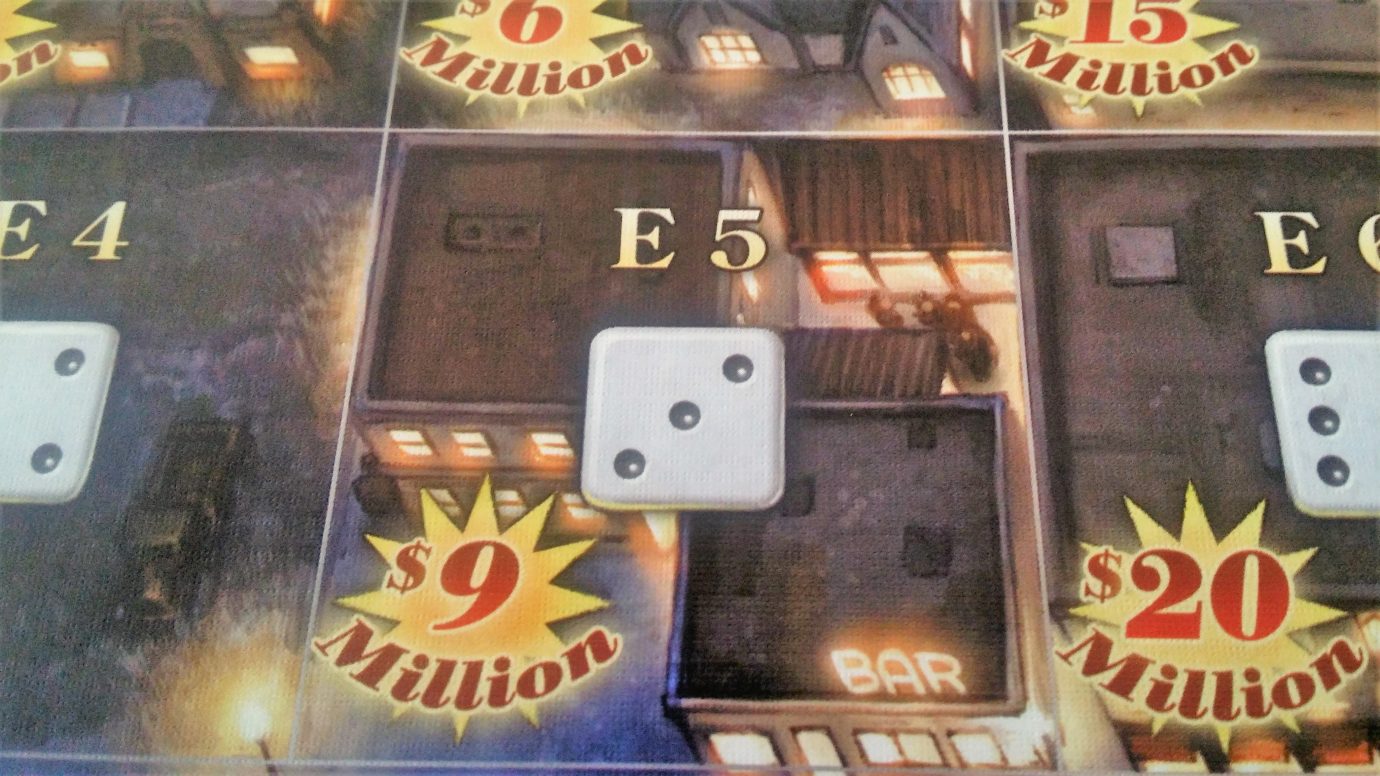

Poor casinos can become rich casinos by careful internal restructuring. By which I mean you are almost certainly paying gangsters to ruthlessly tommy-gun everyone into obedience. The numbers on the pips are profitability, which is a function of influence. One has to assume, given that the casinos are in Vegas, that influence is in itself a function of body-count. By paying the face value of all dice in a casino, you can reroll the lot of them – even those that don’t belong to you. Maybe you’ll turn a two into a five! Maybe you’ll turn a three into a one. THAT’S VEGAS, BABY. Take the chance, maybe you’ll get rich! Turn that tragic joke of a casino into the hottest ticket in town!

The beatings will continue until – well, they’ll just continue.

As you start to build up the Vegas wastelands into a profitable modern Gomorrah, you’ll start to find expansion becomes easier and easier. You’ll have more lots, and they’ll start to appear adjacent to other lots. You’ll buy these up, making small casinos into big casinos, and big casinos into slot-machine cathedrals.

Double or nothing?

Occasionally you’ll ‘sprawl’ into (currently) un-owned adjacent lots at an extortionate mark-up. If someone is later awarded this lot by a card, you’ll lose ownership of that tile. Maybe it won’t come up though, or maybe it’ll come up and you’ll get it. Maybe it’ll be okay! That’s Vegas, it’s all a gamble.

Or maybe you’ll look at the cards that have come out for a particular casino and say ‘Well, that theme is all but played out’. Then you can pay five million per casino tile and entirely remodel the thing. Tired of Roman gladiators? Let’s go Western! Tired of cowboys? Let’s try out Olde World England! It’s costly, but it can reinvigorate a casino that is otherwise stuck with a tired brand. You can escape failing prospects, or buy in early to what you think is going to be a hot ticket.

All of this is nice enough but you’ve only got so many lots you can control, and only so many dice you can place, and only so many tiles of each casino available to buy. Every decision matters massively, but you often won’t know how pivotal it will end up being. When things start getting tight, then it starts to raise tensions. You’re all butting heads against each other, and the game rules start to take on a sinister Machiavellian sheen. Lords of Vegas is, on the surface, a game of buying property and hoping it pays out. Underneath, it’s a game of ruthless area control and hilariously passive-aggressive property management. You may have picked up on the four rules that really ramp up the comedy of competition, but let’s bullet point them.

- You can reorganise a casino in exchange for money, re-rolling all the dice in it.

- The player with the highest die face in a casino owns it.

- A casino is considered to be a single entity made up of all its linked tiles of a given colour.

- Any player can remodel any casino of which they are the boss.

And this fantastic collection of seemingly innocuous rules means that you can take a scenario like this:

There’s nothing to worry about here

Where the red player chooses to reorganise their seemingly independent purple casino for a mere $2m:

Wait, what’s happening?

Only to remodel it into an aqua casino:

Oh. My. God. You are a monster.

And then take control of the much larger casino to which it is now attached!

And if the yellow player wants to make an attempt to regain control? That’ll be $9m to reroll all the dice in the casino, with only a 50/50 chance of success. You can easily lock yourself out of contention with an unlucky reorganisation. Probably best not to, right?

So just like that, red has stolen one of yellow’s key assets from right under them. And the best part is – you can do all of this in a single turn if you’ve got the cash, and it’ll come out of absolutely nowhere. It’s got all the gradual build-up of a drive-by shooting, and leaves you feeling just as injured at the end. That kind of vicious master-stroke is just as often offset by the guy paying $5m per turn to reorganise his sad casino only to find he keeps rolling exactly the same numbers over and over again.

And then there’s the fact that Lords of Vegas lets you trade almost anything for pretty much anything else. You can construct ludicrously convoluted deals, with sub-deals within sub-deals, to create a kind of economic Pandora’s box. Both players come away satisfied, whilst simultaneously feeling, on a Karmic level, that they’ve just been screwed Maybe it’ll be obvious right away as to why. Mrs Meeple once bought from me a particularly lucrative Strip property she couldn’t afford to develop. I instantly used that cash to catapult myself out of poverty and into an unassailable lead. Maybe it’ll take a while for the deal to mature. Either way, this is a game where much of the malevolent property play is vaguely consensual in an asymmetric way.

And you know what else you can do? That’s right, you can gamble! You can pick someone’s casino and say ‘I’m gonna lay down a cool $20m at the table’. The larger a casino is, the more exposed its owner becomes to risk from gambling. The house has an advantage, but it’s not such a great advantage that there isn’t a real risk to someone rocking along with a wad of disposable cash. They roll two dice, and if they get a five, six, seven or eight they’ve got to hand those fat stacks over to you. If they roll anything else, you’ve got to hand the same amount over to then. And if they roll a two or a twelve? They get twice their stake back. You can never lose more money than you have, but it can be very disheartening to watch $40m slink out the door. It’s especially disheartening when your own money is used to absolutely demolish your empire.

It might seem that the key then is ‘little and often’. If small casinos are easier to reorganise and have less exposure to risk, why not just seed dozens of one tile casinos around Vegas? I’ll tell you why – because Vegas is a city of extravagance and your kind don’t belong here. Just look at the scoring track to see why:

Every point matters!

Every point you earn, at least for a while, moves you up the track. Your one tile casino scores, and you move happily from four to five. And then from five to six. But at a certain point you come to a chokepoint:

Getting a little trickier…

And now you need a minimum of two points to move up the track. Each casino is scored individually, and they’re scored one a time from the smallest to the largest. Points don’t accumulate either. A casino of five-tiles is a different beast to five one-tile casinos. The former will allow you to smash your way through to ever greater heights:

How is this even possible??

Your one tile casinos will soon stop mattering as anything other than an incidental money source.

White tiger maulings are up 1000%

And there’s another reason you want big casinos, and another reason why you want the expensive Strip properties. Seeded through the deck are three ‘pay the strip’ cards:

Jackpot!

And when that happens, every casino with a tile that touches the strip pays out. And I mean, the entire casino – every tile in that casino. You want big casinos that stretch from the strip and sprawl over huge lots of property, because a good result from the Strip can be game changing. In one turn you might end up getting fifty or sixty million dollars which suddenly opens up an awful lot of opportunity. Money opens doors in Vegas. A lot of money opens the game.

And so it continues, until the game ending card is drawn. The player that managed to accumulate the most points wins, which will inevitably be the player with the greatest ruthlessness. You can make friends or you can make a name. You can’t do both.

Unfortunately, Lords of Vegas doesn’t end in a crescendo of orgiastic acquisition and violent competition. The middle part of Lords of Vegas is fantastically exciting, with the flip of a card generating elation and depression across the entire table. Gambling can be extremely intoxicating. Reorganisation is tense and electric. Remodelling is beautifully effective and has all the cheerful collegiality of an alleyway stabbing. All of that creates a wonderful frantic energy that keeps everyone engaged, and genuinely interested in what everyone else is doing. That’s when the game peaks, and when it does you can see everyone’s house from the top.

It takes a while before that begins to ramp up. Early turns are ponderously slow as you start accumulating money in drips and drabs. Draw a card, claim a lot, can’t afford anything. ‘Your turn I suppose’. That continues for a while, each turn flipping over another golden opportunity that you couldn’t have afforded. After a while, you get some casinos and some income – once it picks up speed, it keeps accelerating…

… until it reaches the end-game phase, at which point the brakes get deployed so hard everyone gets chronic whiplash. After a while, money is all but worthless because it’s not the financial cost that disincentivises competition, it’s the probability curve. In a big casino, reorganisation is punitively expensive but it’s also highly dependant on how many dice you have in play. When you’d need to put down $30m for an odds on chance at taking control, it’s a lot easier to just say ‘Nah, let’s just see what happens’. You might be willing to risk the loss associated with a sprawl into an un-owned lot. However just as the compressed scoring track incentivises you to build big casinos, it also discourages you from investing in them beyond their utility. A four-tile casino won’t rocket you up the track any faster than a three-tile casino until you reach a particular score. At that point your limiting factor is going to be the casinos everyone else has around you. For the last few turns, I’m rarely even bothering to collect the money I can. I just want the thing to be over. That’s no way to end a game as genuinely thrilling as this one.

That slow and ponderous introduction too has a tendency to exacerbate the impact of chance in a way that hugely distorts the momentum of play. If I build a casino and it pays out three times in a row that success is going to snowball. I might have three or even four casinos by the time someone else gets their first, and by that time I already have an all but untouchable advantage. You can even this out with clever and cunning trade, but only if you can sweet-talk someone into it. After all, nobody is going to want to trade away their own inevitable success. There’s only so much a game based on gambling can do to mitigate this problem though – in general, the rich really do get richer.

So, the ramp up and ramp down of play is somewhat disappointing, but when Lords of Vegas hits top speed it is genuinely something special. It’s easy to forgive it the flattened excitement curve because if nothing else the low-points only serve to highlight the extreme gradient to the high-points. The occasional minutes of ‘when will this get exciting’ or ‘when will this be over’ are the ante you pay for access to the big stake game. I think it’s a price worth paying.