| Game Details | |

|---|---|

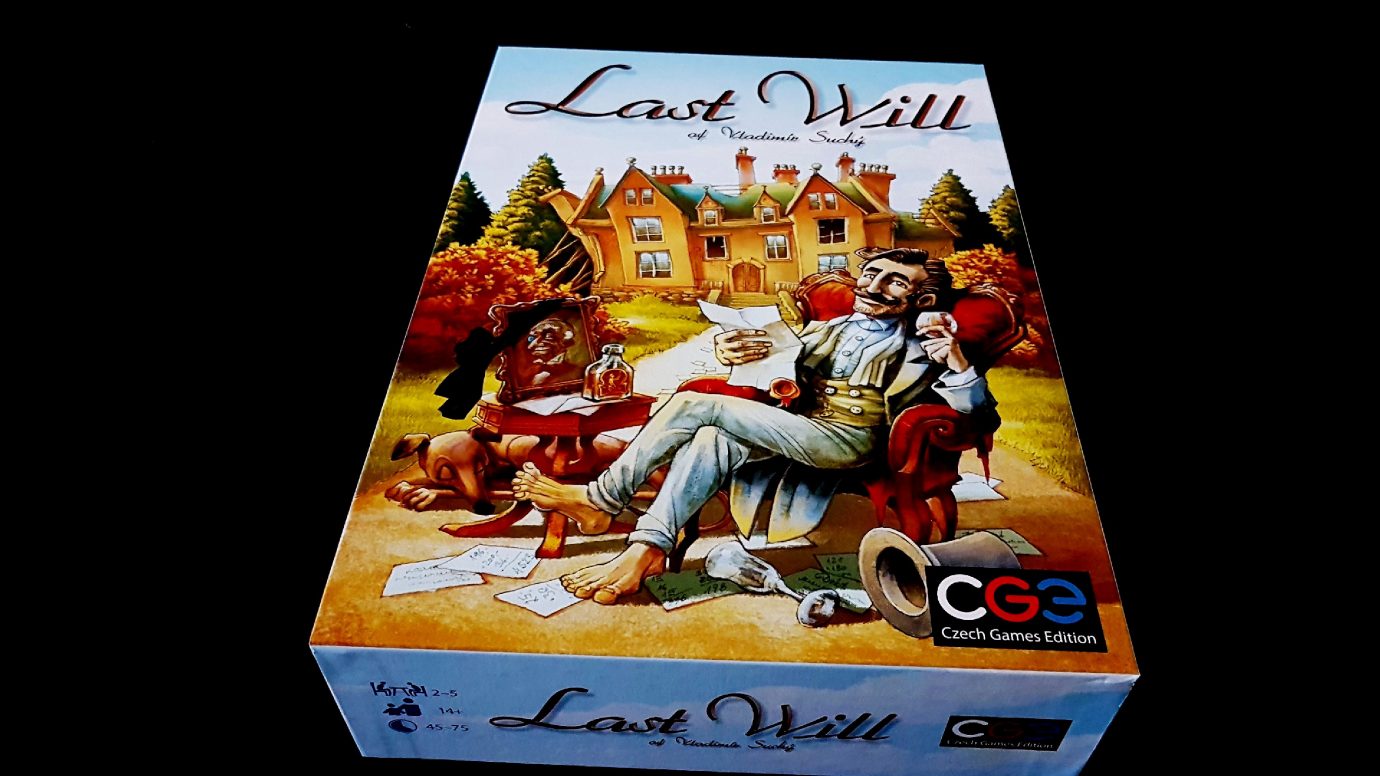

| Name | Last Will (2011) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.71] |

| BGG Rank | 600 [7.17] |

| Player Count | 2-5 |

| Designer(s) | Vladimír Suchý |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

A review copy of Last Will was provided by Czech Games Edition in exchange for a fair and honest review.

Back in the eighties there was a Richard Pryor movie called Brewster’s Millions. It was mostly a typical comedy vehicle of low-grade sexism and shallow social commentary. It was likely cemented in the memory of those that watched it by Pryor’s peculiarly effective synergy of hang-dog cynicism combined with occasional bursts of manic energy. It was a semi-successful semi-modern retelling of the novel of the same name, and it’s also probably the only version of the story most people have encountered. Regardless of the version with which you’re familiar, the story is broadly the same – some lucky sod is in line to inherit a mind-boggling sum of money if only they can prove their financial prudence by futilely pissing a whole pile of other money up against a wall. In the 80s movie, Brewster had to spend $30m in a month in order to inherit $300m. In the original story, it’s $1m to inherit $7m. Whatever the sums involved, it’s hard to feel too sorry for the plight of the protagonist when he is the literal embodiment of the most privileged kind of inherited advantage. In this game you don’t choose the thug life, because that life is simply not on offer. This is the Berkhamshires, and all the thugs are kept miles away from your sprawling country estate.

It’s not just hard to feel sympathy, it’s also hard to take premise seriously because come on – how difficult is to spend a lot of money quickly without accumulating assets? I could do that in my sleep . I’m legendarily bad with money and if it wasn’t for Mrs Meeple I’d spend my days living outside in a garbage can like a Scottish version of Oscar the Grouch. I once exchanged all the money in my pockets for some magic beans. In a tin. In tomato sauce. They were delicious.

Bare feet are a calling card of the landed gentry

And look, here’s Last Will – a game about wastefully spending a vast inheritance just so you can gain a larger vast inheritance at a later date. Last Will is Brewster’s Millions: the board game. It offers the chance for players to really immerse themselves into the culture of conspicuous consumption without having to first drop a platinum selling rap album. It lets you finally prove how easy it is to spend vast sums of money to no meaningful end, and in the process makes you feel smarter about your own financial savvy. After all, look at you – you’ve probably got a mobile phone and a few board games to your name. Even you’ve got assets, and you don’t even have wealthy relatives to enable your debilitating spending habits.

Screw you, ungle pennybags!

Except, you know… this is all a bit harder than it seems really. The key constraint within any version of the Brewster’s Million’s tale is the importance of transience. You can’t simply spend the money, you need to spend the money without accumulating possessions. You can’t simply dump it all in the stock market, because those shares are still entries in your financial ledger. You can’t simply buy properties, because all you’re doing is changing the nature of your assets. Those are ‘problems’ that most of the audience for stories like this often can’t really appreciate.

When you’re within spitting distance of the breadline, every penny is temporary. You spend your money on rent, which goes into someone else’s pocket. You spend it on food, which gets eaten over the course of the week to give you the energy needed to shovel more money into the pockets of other people. You spend it on electricity, on gas, on heat. You spend it on diversions to make you feel better about the financial trap in which you find yourself. The capitalist system is intensely cruel and it’s a pyramid scheme built on human suffering. In order for some people to succeed, many others must fail. In order for one person to become rich, many others must become poor. That’s great if you can convince yourself that it is through the merits of your own endeavours that you deserve your lofty position on the backs of others. It’s not so great if you’re the one with aching shoulders because of all the weight you’re carrying. For many people, the idea that money can be made to work for you rather than work for other people is laughable. Many people don’t even have enough to satisfy all the demands other people have on their money.

There is though an important pivoting that occurs and it’s the where you switch between being one pound overdrawn at the end of the month and being one pound in surplus. It’s a hidden pressure in the system that creates intense feelings of sadness and stress because while the difference may only be a couple of quid there is a psychological grand canyon between them. On one side is ‘all your money goes to other people’ and on the other is ‘some money is available for other pursuits’. They say ‘money brings its own worries’ but it’s fair to say those worries are rarely quite so psychologically debilitating as those that are associated without having money.

That’s a long, only semi-relevant digression but it brings us back into the territory of Last Will’s theme – you’re not in the position of having to simply meet your transient needs. You’re on the other side of the chasm, and on that side the capitalist system inverts. Less and less of your money, proportionally, needs to be given to other people and instead wealth becomes a more fungible proposition. The real difference between renting a property and buying a property isn’t in terms of monthly costs – it’s in terms of what the money you spend is doing for your portfolio. Last Will then is the gamification of this point of inversion – where spending money uselessly isn’t a passive activity but something that involves planning and active choice. You can’t just buy ‘food’, you need to have a lavish dinner experience. You don’t just get on a bus and go to Finchley, you have to charter a yacht to take you on an indulgent cruise. You can buy property, but you have to do so with an eye on the market and the depreciation that you can hopefully bring to bear through carefully weaponised neglect. You need an army of hangers on to claw at your wallet. You need to really suck at the marrow of life, because everything else is a net contributor to your bottom line. You need to end the game without assets and all the game systems are designed to make that as difficult as possible.

London’s Calling

There’s another factor here that complicates spending of money within Last Will and that’s time. One of the stipulations of your uncle’s last will is that you actually enjoy the fortune he is leaving for you. That means you can’t just take the whole of London out for dinner – you need to be a meaningful part of everything that’s going on. If you’ve got an entourage, they need to be draining you dry. For that, your teat has to be right there in their hungry, parasitic mouths. You can make standing arrangements, but making use of them is an activity that consumes time and you don’t have enough hours in the day to spend this money you have. As such, you need to find a balance between passive ways to lose money and more proactive acts of self-inflicted bankruptcy.

Hatisfied with these choices

And the problem here is that you’re not the only relative in with a chance of the big prize – all your other wastrel cousins likewise are licking their lips in anticipation of all that free wealth trickling their way. As such, opportunities are often highly contentious and the long term aspirations of each of you will have considerable impact on the others. Nowhere is this more markedly implemented than in the action space tracker made available – each player gets to decide on when they’re getting up in the morning and that has a powerful effect on the economies of the day. Your waking time determines how many cards you’l draw, how many errand boys you’ll have available, and how many actions you’ll have to be able do things. The earlier you get up, the earlier you get to act but the down-side is that you’ll be so tired and listless that you might not be able to accomplish much. The later you get up, the more rested you’ll be but you’ll also be picking at the leavings everyone else has deemed not worth their attention.

Your estate, sire

Your job in the game is to develop and leverage the tools needed to properly spend money in its most pure and efficient form. Each turn, you’ll draw a handful of cards and decide on what you want to do with them. Some, with black borders, represent persistent resources that get played down to your player board. These always cost one of your precious actions but they usually give you opportunities for regularly and reliably spending money. If they don’t, they’ll give you special powers that can be used to more efficiently construct your engine of deacquisition. You’re not only contending with time here, you’re also trying to navigate the elasticity of the opportunities you are presented – you’ve got hand limits to deal with, and these mean you can’t simply hold on to all the most lucrative activities with which you are presented. Some useful people can let you keep more of those, or draw more during your turn. They usually don’t cost you any money, but their charitable and well-meaning natures might be worth putting up with if they help you more effectively lose your wealth in other parts of the game.

It’s good to have land

You’ll also get a bevvy of property opportunities that come your way, and property represents potentially actionable expenses but also one of the few changes you get to passively lose money. Farms retain their value, but everything else depreciates over time – as long as you’re not making use of the property, they’ll drop in value turn by turn until you can sell them on at a hopefully huge loss. While you have a property you can’t go bankrupt and you can’t go into debt, but they are huge money investments that permit a player to potentially lose a lot more than more active, lived experiences might permit. Owning a house after all is like making a blood pact with the relentless forces of entropy – they demand their dues through regular excoriation of your bank account.

This is pre-Brexit of course. Otherwise they’d all be much more negative

The thing about wealth though is that it more often brings solutions than it does problems. Buying property is a risky business, but you can always make use of your power and influence to juggle the real estate market a little. You can send one of your errand boys there and you’ll get to rearrange markers so that you can buy high and sell low. Sure, that farm might hold its value pretty well but if you buy it at three million above the market price and sell it for three million under… well, that’s not bad for something that was literally just a water-logged field in some god-forsaken part of New Clottinghamshire. In the meantime, you might be able to fill it full of dogs and horses and other expensive animals and maybe even enjoy their company for a bit if you can spare the time.

Friends you haven’t met yet

Other opportunities available to your errand boys are cards that are played out to the shared board, and some of these are unavailable through other means. Here you might buy cards that give you extra actions in a turn, or special chums that give passive actions through the course of the game. You might find special events that let you spend staggering amounts of money in exchange for an equally staggering investments of time. Time is money friend, as the goblins say – it follows then that money is also time. You’ve got money! By spending it on people willing to do favours for you, it ends up freeing a lot of time. Such is the algebra of capitalism, and you need to be something of a mathemagician if you’re going to get rid of this cash before the time runs out.

This is a little dodgy. You know – because of the implication.

Sometimes though you’re not investing, you are participating – black bordered cards go down to the board, but white bordered cards are one-off events you can simply enjoy – perhaps with a companion if you have a compatible one in your hand. Do you fancy going on a lovely boat trip with a charming lady companion? It’ll cost you two actions, but it’ll mean you get to spend four… million?… pounds on it. I’m not 100% sure the economy in Last Will is accurately modeled – I can see spending four pounds on a boat trip, but not ten pounds on a farm. I can see spending ten million pounds on a farm, but not four million on a boat trip. How small is this farm? How long is this boat trip? How… uh… expensive is this companion? Is this fee hourly? What exactly is the nature of the relationship I’m buying here?

It doesn’t matter, never mind! It honestly doesn’t matter, because I don’t even know if you noticed just how funny Last Will gets at points like this. Look at the boat trip again! You can take a dog and a chef along if you like, and the dog costs more to bring than the guest. What’s all that about? That’s a design decision I am 100% on board with because humanity as a species simply isn’t good enough to deserve dogs – they deserve to be valued highly. But this kind of implied comedy is threaded all the way through Last Will – you can certainly make a po-faced explanation for why you need a horse to get to the theatre, but I much prefer imagining it was simply a play you thought the horse would like to see. Similarly when you take a dog out to dinner or send three of them off to live by themselves on a farm. There’s a school chum that can… ‘procure’ you three companions each round – no cost, no questions asked. There’s a sea dog you can bring into your entourage that makes both sailing and banquets more expensive, and you have to wonder what skillset he brings that makes him an appropriate guest for both of those activities. There are funny stories you can tell about all of this, and that’s all supported tremendously well by the art and the theme. Last Will is a game that has made me laugh out loud with its absurdly comic juxtapositions on a number of occasions. It’s obviously knowing too, since some the art subtly changes depending on the companions you might bring with you during an event. This results in scenarios straight out of an Ealing farce where you might take a carriage ride with a lady friend and arrive at dinner with two different ladies and no hint given as to why. Your protagonist in Last Will has all the bemused affability of Bertie Wooster, and you can even hire a Jeeves to valet for him if you feel the need.

Time to get things done!

Coupled to this is a real sense of pacing built into the gameplay mechanics – purchasing properties for example will become less sensible the longer the game goes on. Rather than still have them clog up the opportunities deck like sad ‘help wanted’ ads in a regional newspaper, Last Will simply gradually cycles them out of contention. That means just as you’re no longer seeing properties regularly come up for sale you realise that you’re screwed unless you can somehow get rid of the ones you already have. That in turn creates great moments in play where you realise that your masterplan for success somehow, unaccountably, forgot that you had twenty million tied up in property you still need to get rid of before the final whistle sounds. And, of course, that twenty million is also going to need to go before you can finally consider yourself divested of this turbulent wealth. Last Will is part about building an effective engine for generating expenditure, but it’s also about dismantling that engine while you still have time to sell off the parts and fritter away the profits.

Last Will is definitely a good game, but it’s also not a game that I can easily recommend without complications. I had a lot of fun with this in the last game we played, but the truth of the matter is that I had to kind of force myself to play it the third time. I won’t review a game for Meeple Like Us until it’s been played at least three times, and more still if I feel the game still has mysteries left to unlock. My first exposure to Last Will didn’t make a positive first impression because for such a light, breezy and comic game it’s also strangely bureaucratic in its mechanisms. It’s full of ‘you can do this, unless this, except’ and cards that have different effects and ways to be played depending on how they’re to be used. Guests generate tokens for assets, but also get played as supplements to events. Wild-cards act as general guests that you can only hold temporarily for a round until they bounce back to the board. Farms don’t depreciate but all other properties do, and so on. No individual rule here is difficult, but it all feels just a touch too clumsy and clunky for the theme. My second play of the game was a bit freer, but still involved a lot of cross-checking with the often perverse symbolism used on each of the cards. It takes quite a bit of time before you can play this without having the rule-book handy.

Most of the gentry learn this kind of thing at public school

Once you’ve internalised most of this it plays smoothly enough – It’s not complicated in any real sense, but it feels complicated. This is compounded by the fact that there isn’t an especially easy way to look up specific queries in the manual. Finding a new special power on a card remains a job of scanning the index at the back hoping to see what you want, and if there are four or five of them to consider at any one time it adds a fair bit of awkwardness to the proceedings. It’s like being at a restaurant where you need to scan a menu in a foreign language every time the waiter asks you a new question.

Coupled to this is that while the theme is very well expressed throughout, it doesn’t quite have those elements of the Brewster’s Millions style stories that I like the most. There’s an enjoyable eurogame of futile wealth disposable here. I think though the real dark comedy from a premise like this is to be found deeper in the systems of capitalism that are being lampooned. They come when Brewster dumps millions on sure-fire loss bets and ends up making a massive profit on a few unexpected results. They come from buying a ridiculously expensive collectible stamp and using it to send a post-card. They come from his starting up a ludicrous car-crash political campaign and ending up as President of the United States. Wait, no – that’s a different super-rich, dangerously incompetent clown. They come from his genuine friends looking to save him from himself, and from the agents of the bank actively sabotaging his efforts so they can keep the money for themselves. I’m not looking for Brewster’s Millions to be replicated in cardboard. I would have enjoyed the game more though had Last Will been about the social dynamics of people and wealth rather than a more mechanical take on hand-management in a worker-placement context. Short of the property assets in Last Will, there are few opportunities to be surprised at how the capitalist system bites back at those that attempt to subvert it. Nothing ever feels uncertain here. You’re never in any real doubt you’re going to spend all your uncle’s money – it’s just if you’re going to do it quickly enough.

That’s fun enough and I can’t really begrudge a game for not being a pointed, subversive tragi-comic commentary on the capitalist system since I suspect the audience for that game might end up being just me. Or you know – since that’s also what Monopoly was supposed to be the audience might well end up being the entire world once the sharper edges are knocked off by the capitalist system it was supposed to satirise. Last will is a good game. Last will is a funny game. But Last Will is also a game that needs you to be willing to persevere past the rocky learning curve. It’s worth doing that though because there are no other games I can think of with a theme remotely like it. Also, given the state of the world and the economy it’s probably the only remaining chance most people will ever get to own a property of their very own.

A review copy of Last Will was provided by Czech Games Edition in exchange for a fair and honest review.