Table of Contents

Scoundrels of Skullport is an expansion to Lords of Waterdeep and requires the base game to play.

Version Reviewed

Introduction

This review is best considered to be a ‘Director’s Expanded Edition’ of the relevant accessibility teardown – in this case, it’s Lords of Waterdeep.

Scoundrels of Skullport is an expansion that I personally consider to be must buy – it adds so much deliciousness to the base game that the unseasoned meal now seems a little bland. While I could certainly enjoy playing Waterdeep without Scoundrels of Skullport, I can’t imagine a situation in which I’d choose to do so. So, let’s say you have the game – what does it change in terms of the accessibility profile if you pair it with the expansion? Let’s see if we can shed our corruption as we explore the expanses of Undermountain.

Colour Blindness

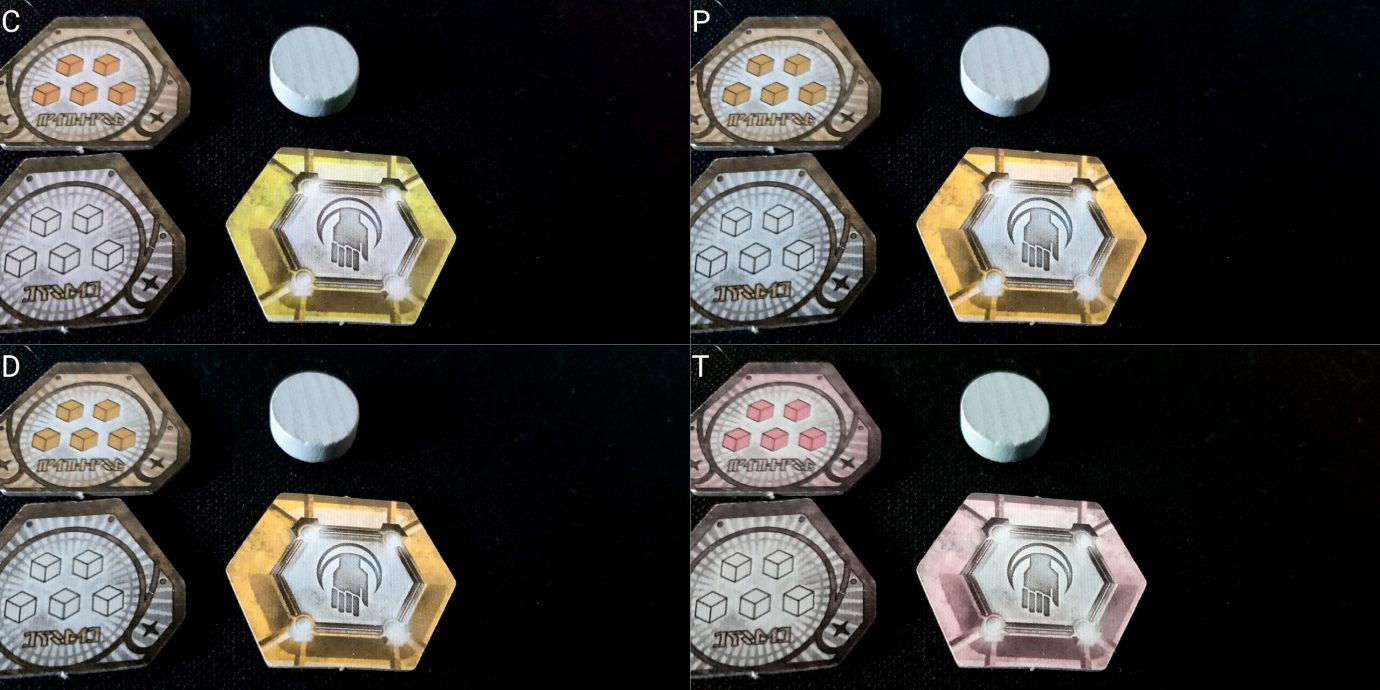

The sixth player introduced to Lords of Waterdeep makes use of a grey identifier which won’t clash with any of those present in the existing game. The additional upside of this is that it loosens up colour restrictions in the base game too – it means that if colour clashes with existing agents are a problem, there’s a bit more give at lower player counts.

Grey as the morality within which you operate

The five-adventurer tokens are actually a little easier to differentiate than the cubes are, and the corruption token is of a noticeably different design. So this actually makes the game somewhat more accessible in this category. It doesn’t seriously upgrade the rating because, in the end, adventurer cubes are still the default currency of play. However, you gain rather than lose accessibility here through the adoption of Skullport.

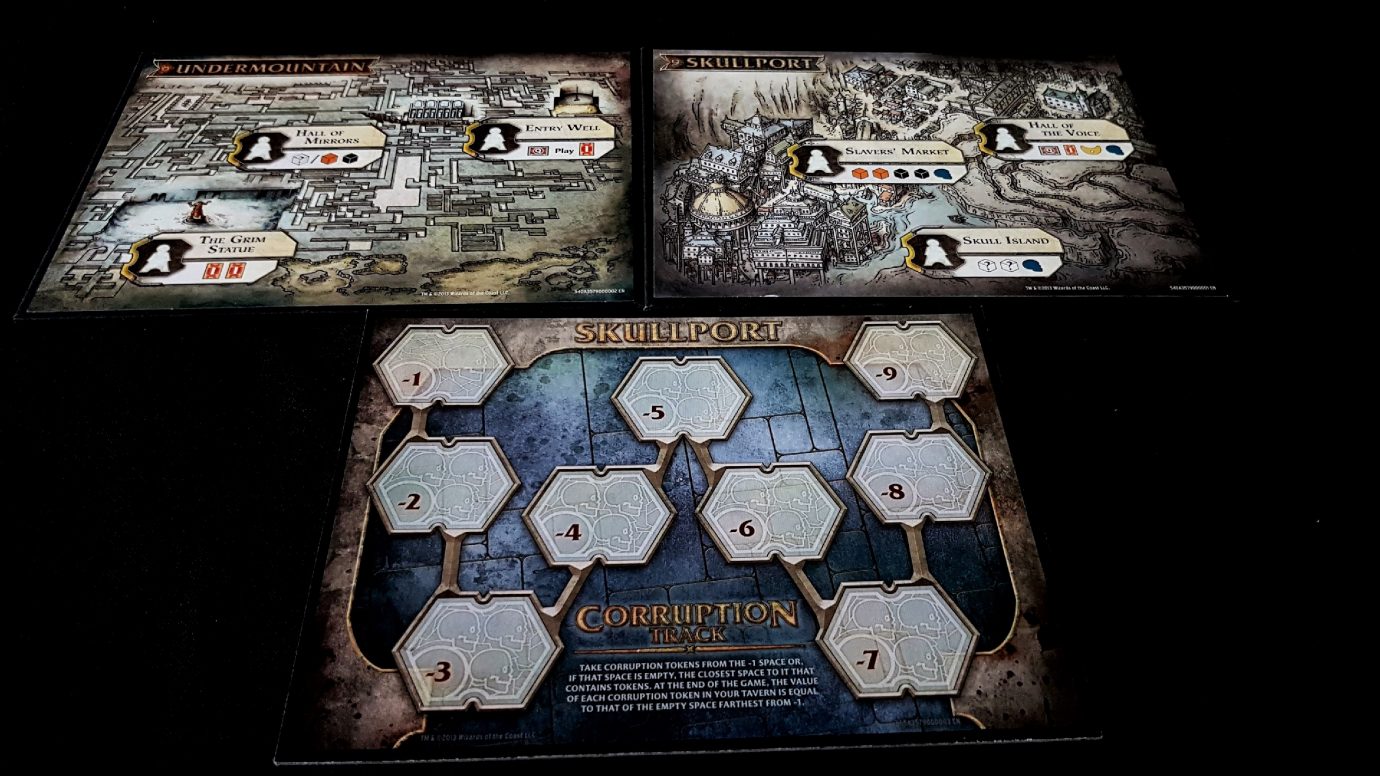

Visual Accessibility

A problematic game becomes more problematic in this category – the two expansion modules both introduce side-maps into play. Corruption is a major mechanic if you’re making use of Skullport, and knowing how many tokens each of your opponents are juggling adds an additional layer of necessary book-keeping to play. That needs cross-referenced constantly against the corruption track and how many tokens are actually available – that may not be the same number as how many there were at the start. If using both expansions, three additional side-boards are put into play – they can be put where it’s most convenient for easy viewing, but sprawling information is already an issue with Lords of Waterdeep and the expansion very much doubles down on that.

Three board Skullport, that’s what they call me.

Quest cards in the game, as a consequence of the fact they have interesting rewards other than just victory points, now often come with a chunk of text that needs to be read. Some of these effects are relatively complex, with dense information represented only in the textual components of the card.

Excitingly varied

Consider Obtain Builders’ Plans above – not only is the text quite verbose, it also comes with icons threaded within the writing. The agent icon, if viewed by a player with high visual acuity, is reasonably distinctive. However, it’s easily confused for a black rogue cube in scenarios of low differentiation. It doesn’t make a huge difference over what’s in the original, but it certainly doesn’t improve upon it.

The new modules also introduce an additional complexity into play – resources may now be placed on action spaces as a result of certain quests, intrigues and buildings. That means that previously constructed mental models of risk versus reward may need re-evaluated in light of player actions – true, they need nudged rather than rebuilt from the ground up, but it’s still ‘one more thing’ that needs to be considered in a game that was already somewhat visually inaccessible.

We already strongly recommend those with visual impairments avoid Lords of Waterdeep, but we’d strengthen that guidance considerably for those adopting the expansion.

Cognitive Accessibility

Lords of Waterdeep is mechanically light. However, the expansion invigorates these somewhat simplistic systems with a whole mess of new content. Very few of the newly spiced mechanics are deeply synergistic (you rarely have buildings or quests that feed directly into others) but there is suddenly a new depth to strategic thinking that was previously missing. Some quests rewards will be directly useful for other quests, and sometimes there will be an element of optionality in how rewards are to be handled. This is true of both modules – it makes the game much more interesting, but it also makes it less cognitively accessible. ‘All the quests you are trying to complete are thankfully relatively simple to understand’, is what we said in our original teardown. That is no longer true. The risk and reward of play is now variable, and tightly coupled to an emergent and evolving economic context. Corruption is an extreme example of this, but not the only one. Decisions that always made sense in the base-game might offer only conditional applicability in the expansion.

The system of corruption too adds a new need for explicit and implicit numeracy. The cost of these tokens will grow and shrink over the course of play. Understanding what it means to take a corruption token needs players to appreciate the long term implications. You’re essentially leveraging a short-term capital investment against a long-term cost – it doesn’t require anyone to be able to do the arithmetic, but it does require an appreciation of changing value in an ever-shifting economy.

It’s true you don’t need to include any of these systems, but then all you’ll get from the expansion is support for a sixth player. These elements are too tightly coupled into the quest, intrigue and building designs to mix and match without serious and detrimental gameplay impact.

We shall overcome

The situation for those with memory impairments is less bleak because the corruption tokens and temporary resources on action spaces are all visually represented. The corruption track too shows the impact each token has, prominently displayed on the board. There is no new information that needs to be held entirely in memory.

As such, Lords of Waterdeep with Skullport is noticeably les accessible to those with fluid intelligence impairments, but approximately the same for those with memory impairments.

Emotiveness

In the base game, the only real potential emotional flashpoint is in the mandatory quest cards. That’s not true in the expansion – it’s a much meaner game, even if only as a consequence of the fact intrigue cards are easier to get and easier to play. It would be more confrontational even if there weren’t brutal new opportunities for player interaction. It’s telling that of the new intrigue cards either module provides, very few of them are mandatory quests – they don’t need to be. You can steal things directly from a player, burn down their buildings, or even steal their buildings out from under them. The intrigue system is much more useful in Scoundrels of Skullport, but it’s also much more pointed.

The corruption system too is a point of player interaction that might be risky if dealing with emotional control conditions. Access to amenities that remove corruption from your tavern is contingent on other players, and there are usually only a few of them in play in any given game. It’s possible that you’ll be locked out of the ability to meaningfully manage corruption while other players gleefully seed it onto the action squares most important to you. It’s also easy to misjudge the risk of corruption because its eventual penalty value is a communal calculation. You might be compelled to pick up corruption as others discard it as the cost of any individual token goes down. It’s a bit like buying a stock when it’s plummeting in value in the hope you make an overall profit in the end. However, canny corruption management is a powerful gameplay tool and you might find people simply burning corruption from the track, discarding it from the game entirely, purely to increase your penalty at the end. There is no reason to discard corruption from the game other than to make it more costly for other players. It can’t be interpreted as ‘Well, I had to do this, sorry you got burned’. This is more wilfully gleeful. It’s a great mechanic, but one that carries with it risk in this category.

We’ll still offer a tentative recommendation here. Scoundrels of Skullport definitely makes for a much meaner game though.

Physical Accessibility

The new boards add in a little more spatial management, and the corruption tokens are just one more thing that needs physically manipulated. Seeding action spaces with resources too introduces a new wrinkle in play – the risk that these might be dislodged and end up adjacent to a different square on the board.

However, the fact that the boards are provided in three separate sections means that you can position them for maximum physical accessibility. Really this is something I think I would have liked to have seen in the main game – modularity in these kind of boards permits for maximum accessibility. We’ll degrade our rating slightly here because the new boards, for all their flexibility, do add to the sprawl of the game. However, this doesn’t change our overall recommendation category.

Communication

Nothing significantly changes here, although there is a slightly higher reading level required of players as a result of the additional complexity in quest and intrigue cards. Nothing to overly worry about. The average reading level goes up somewhat, but the ceiling remains roughly the same. We’ll keep our rating here as it was for the base game.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

Of the six new Lords available, three are men, one is a woman, and two are monsters of one form or another. It’s not great, and doesn’t improve what was already a disappointing balance from the base game. The artwork is approximately the same when women are shown in quest and intrigue cards, but they are noticeably absent otherwise throughout. We’re not going to adjust our rating on those grounds, largely because we already complained about many of these issues in our original teardown. They don’t become worse, they just don’t improve.

The RRP of Scoundrels of Skullport is a hefty £33. That’s pricey but you can sometimes pick it up for around £25 (which is what I did). You do get a fair amount for your money – lots of new buildings, lots of new quests, lots of new intrigue cards, and scope for adding a sixth player. This isn’t just ‘adds new content’ either, this meaningfully improves the quality of the game experience. It’s not that Lords of Waterdeep is a bad game without this – it’s just all a bit sterile. Scoundrels of Skullport makes it the game it should have been to begin with. I think it’s worth the money for what it does.

Our grade here then remains unaffected.

Intersectional Issues

There’s only one new intersectional issue that becomes relevant here – playing with a single expansion module lengthens the game somewhat, but playing with two lengthens it a lot. The rule for this is even called ‘Long game’, where everyone gets an additional agent. To be fair, Lords of Waterdeep doesn’t take up ridiculous amounts of time even with the expansion, but it’s a game that requires continual attention because turns are interleaved. So, ‘just like Lords of Waterdeep, but for a longer period of time’. You can get around this by playing one expansion or the other, but I really think that you need both to get the best effect. This shouldn’t be a deal-breaker, but it’s something you should bear in mind.

Conclusion

Unsurprisingly, adding in a whole new pile of interesting gameplay systems and interlocking effects makes a game less cognitively accessible. Adding in more things to keep track of makes it less visually accessible. Adding in more physical sprawl makes it more physically inaccessible. None of these things should be a surprise.

What’s more surprising is that the expansion doesn’t flip recommendations, it just strengthens them. Scoundrels of Skullport permits a highly concentrated version of Lords of Waterdeep – everything it has is more so. Our glowing review says this turns an eight out of ten into a nine out of ten, and we don’t go higher than that here. At least, not so far.

Scoundrels of Skullport then, is excellent. It’s clear the designers looked at the base game and wondered ‘Where’s the fun in this?’ and then built an expansion that brought those elements more clearly to the surface. In the process, they turned that which was good into that which is great. If you liked the original and were able to play it, you shouldn’t shy away from giving the expansion a try.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.