Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Decrypto (2018) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.81] |

| BGG Rank | 99 [7.77] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 3-8 (4-8) |

| Designer(s) | Thomas Dagenais-Lespérance |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

Codenames is a well regarded game, but Decrypto is the title in that approximate area of the ludic landscape that I’m most keen to play. It’s full of its own quiet and inventive charm and solve a number of the problems I have with its more popular cousin. Codenames can feel a little like you’re not part of the fun at all when it’s not your turn. Decrypto in comparison turns the act of conferring into a tense and risky spectator sport. It’s really nice, and that’s why we gave it four stars in our review. It evicted Codenames from my shelves and I don’t feel a tiny bit sorry about that.

That said, Codenames is a strong performer in the accessibility stakes provided you’re okay with a game that stresses cognitive and language factors and don’t mind the use of external tools. Whether or not Decrypto is going to receive as fulsome an endorsement in the teardown remains to be seen. Get your cipher-breaking tools, we’re going to crack this thing wide open.

Colour Blindness

Most of the game doesn’t use colour as a channel of information. However the keywords are encoded on cards that only show off their contents when slotted into the provided code boards. That has Implications.

Colour blindness does not seem to be a problem with this due to the relatively high contrast, in all standard categories, of the text and the background. However, ‘standard categories’ is the caveat – there is no such thing as a colour blind accessible colour palette – just palettes that work better than others. As such I would be unwilling to offer a full-throated recommendation in all circumstances without a lot more testing than we’d be able to do. It’s probably going to be okay except in very rare manifestations of the condition.

Other than this, colour doesn’t play a role in the game – the only other components are the combination cards (fine), the two different kinds of tokens (also fine) and a notepad (fine too).

We’ll strongly recommend Decrypto in this category, with the proviso that we can’t actually test it in all the circumstances that would be needed to really give the necessary confidence that the grade would stand up under robust investigation.

Visual Accessibility

The design of the game is actually reasonably well set up to support play for those with visual impairments, although there are going to be some complications. First of all, the code boards are not optimally designed for readability and the game cannot be easily played without them. They take obfuscated graphical information and turn it into the keywords that are the core to the game experience.

Those with visual impairments may find the text somewhat difficult to read, although close examination will be sufficient in most circumstances to address that. For those for whom that’s not possible will have a slightly more problematic time with the game.

That said, there are only four keywords and provided a sighted player is on the team they can be indicated quietly to a visually impaired player. The words and their position matter but it’s not an unreasonable memory burden for someone to hold this in mind during play. The slight risk here is that conveying the keywords verbally runs the risk of the other team overhearing and so it may be necessary to move out of earshot. The words don’t change during the course of the game so this need only be done once at the start of play and again whenever a reminder is required.

Playing the role of the encryptor is going to be a more difficult task if the code cannot be read from the card since this is information that should properly belong only to the that player and not to anyone else. The codes are reasonably large but they are not very well contrasted, and close inspection runs the risk of revealing the contents of the card to those that should not see the secret information. That said, there’s nothing really to stop players adopting a different approach to the game – such as permitting the player to decide, in advance, on their own combination.

Technically speaking the encryptor for a team should write down their clues and pass them over for the teammate(s) to read out but it has very little effect on the game for the encryptor to simply verbalise the clues. It could be argued that this offers a team an additional way to offer guidance through, for example, intonation and pronunciation. The set of circumstances under which that is likely to offer a gameplay advantage seems to be quite small.

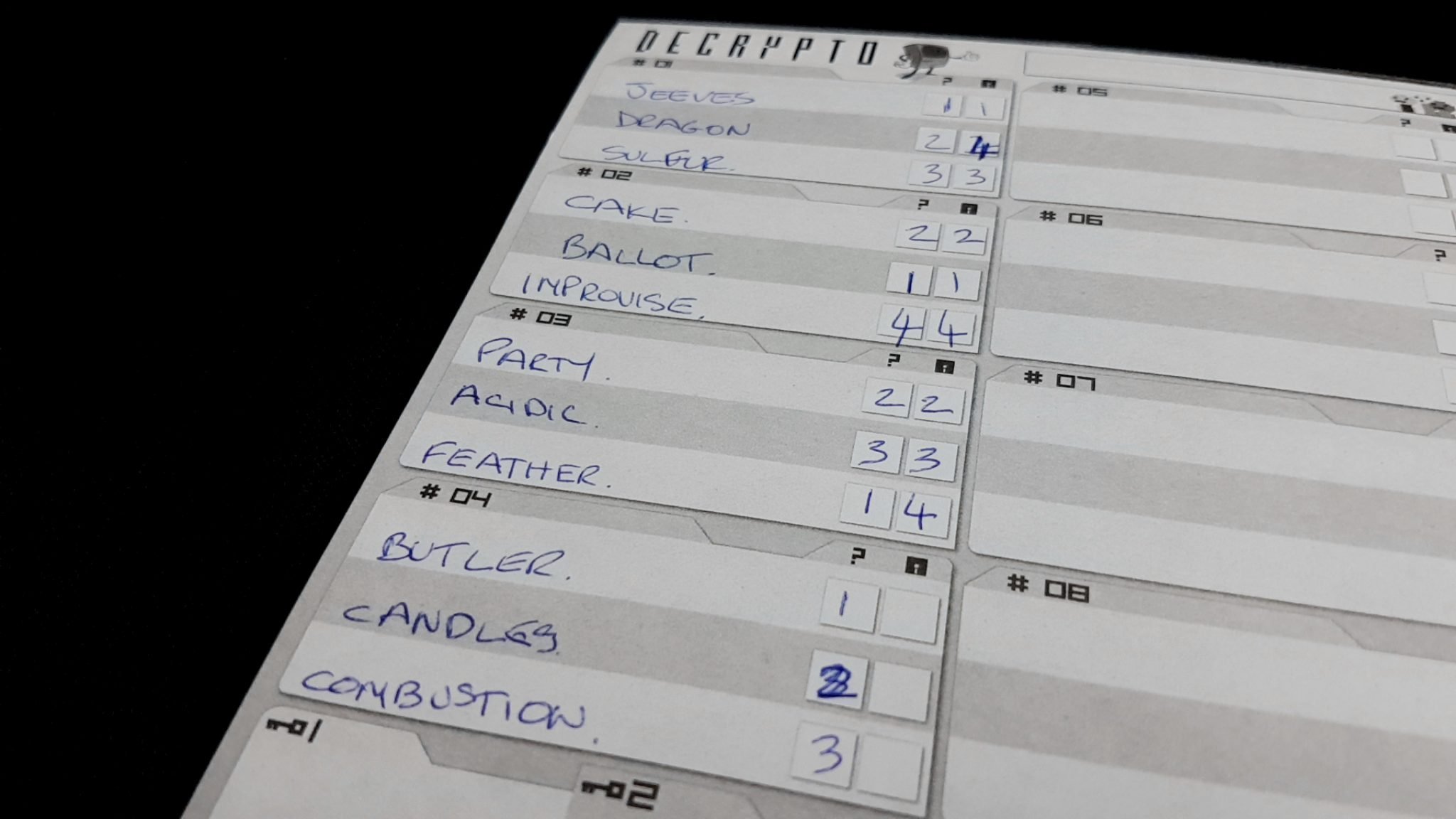

Taking notes is an important part of the game but the use of the provided notepads is not actually required. The only thing that would be necessary was that whatever written format was used did not permit teams to peek at the guesses each other made. There are many ways that can be done, including through the use of tablets and laptops.

Other than this, Decrypto is a game that is played verbally and aurally, and the main bulk of the game should present no obstacle to play. We recommend Decrypto in this category.

Cognitive Accessibility

Decrypto asks a lot of its players with regards to cognitive faculties. While it doesn’t have the same exploding possibility space as Codenames it does explore a similarly costly domain of thought – semantic reasoning. Consider the word PRESENT. The job of both the encryptor and the guesser is to work out which clues are a best fit for the words in the grid, taking into account the fact that clues can’t repeat. PRESENT though gives us several possible definitions:

- A gift

- This present time period

- The physical presence of a person

- To formally give something to someone

- To introduce someone

- The way we exhibit ourselves to others

And so on, and so on. Good clues will be unambiguous but also will likely cross over these definitional categories . I might say WRAPPING PAPER as a clue. I might also say ATTENDENCE. I might say HAVE YOU MET MY WIFE, or any number of other things. Having too many clues in the same rough semantic orbit risks the clue becoming obvious to my opponents. Picking good clues is cognitively expensive. It’s an easier task to map clues to words if you know what the words are, but in skillful play it’s still not going to be easy because of the need to mislead the other team.

This gets even more fraught when considering what it means to break the codes of your opponent. Let’s say you get the following clues that are linked to word two.

- DIY

- ART GALLERY

- POT

- DÉCOR

This is a case of reverse engineering – not so much of the word, but of the approximate space an unknown word occupies in a person’s vocabulary. If the next clue comes along as MONA LISA you might think ‘Oh, I can see a relationship between that and the other words’ but opponents are intentionally going to be trying to make that difficult. You only need to guess the actual word in tie-breakers but even linking words together into a theme can be tricky. Then you layer in the fact there are four words and the opponent team will be trying to find ways to make one word look like it’s linked to another and vice versa. You need a good command of a language, including antonyms and homonyms, to really be able to navigate this tricky territory.

The reading level isn’t particularly high, given that all a player must read is a single word. The expectations of vocabulary though are extensive and will often involve words drawn from history, mythology or folkloric tradition. It’s possible to ask for a definition of your team members since you all know the words but that’s going to peg the possibility space of clues around what everyone knows of the shared definition. If our only known and shared definition of centaur is ‘half-human half-horse’ we might not want to give clues focused around the idea that the astrological sign of Sagittarius is traditionally associated with centaurs. The rules require all clues involve public information, but that’s not the same thing as public comprehension or even public knowledge. By that I mean you can’t rely on an in-joke or a secret signal but you can work with the fact that not everyone knows the same ‘public information’ as everyone else. There’s a strong emphasis as a result on general knowledge and the ability to make sometimes obscure associations.

In terms of memory alone, Decrypto does a good job of making sure everything is recorded during play. All clues are written down, all guesses are likewise, and there are physical indicators of all the different moving parts of game state.

We don’t recommend Decrypto in our fluid intelligence category but we recommend it for those for whom memory impairments alone must be taken into account.

Emotional Accessibility

The only real concern I have here is in the relatively high percentage chance that a random guess will reveal the correct answer purely because of the small number of possible combinations. While this doesn’t impact on the amount of information your opponents have, it does massively skew victory towards them when it happens. You only need to successfully intercept two messages to win, after all. It’s like someone guessing your password by randomly typing on the keyboard.

Similarly, as soon as one number is reliably deducible it reduces the number of possibilities that need be considered for the others. It’s possible for someone to narrow in on your code easily and with skill only playing a partial role. That’s frustrating and feels unfair, because that’s exactly what it is.

I don’t want to overstate this though – it happens only occasionally and it’s not something that hugely undermines play over the long term. Other than this, there’s nothing to be particularly concerned about in this category. We’ll strongly recommend it here.

Physical Accessibility

Part of the setup of the game involves taking relatively flimsy cards and slotting them comfortably into the code boards. The cards are prone to bending and the fit is very snug so there’s a little bit of wrestling the components into obedience if fine-grained motor control is likely to be an issue.

There’s also a need to write (or remember) clues and combinations that have been given but these need not be done by any particular player on a team. Indeed, aside from making a guess, they don’t even need to be done by a team. If writing a guess in secret is likely to be an issue it’s relatively easily solved by having one team write their answer and for another to verbally reveal it. If that is not appropriate, other techniques can be used to indicate a guess since that only involves three numbers.

If a player with severe physical impairments is acting as the encryptor they may perhaps need have the code shown to them in a way that doesn’t reveal it to anyone else at the table but is still visible to them. This can either be done by briefly holding it in front of them or slotting it into a card holder.

Other than this it’s a game of talking and listening and as such we recommend Decrypto in this category.

Communication

Ah, here’s our stumble category. Decrypto stresses communicative faculties both in terms of vocabulary and expression. The clues in Codenames tend to be small and succinct but while Decrypto requires you to consider fewer words at a time it needs you to engage more subtly with them. Clues can be statements, interpretative and more – the only restriction is that they have to relate to the meaning. You need a solid and occasionally sophisticated grasp of all the possible ways in which meaning can be interpreted.

Play within Decrypto is also a task of active listening as you try to ascertain the clues that players on the other team discuss. Nuance in expression and pronunciation is going to be important here and it will reveal assumptions and expectations that might not otherwise be discernible. Clues are supposed to be written down, but the discussion around them between team members is not. The result is a game that does expect players to be able to hear clearly and also to participate in some ‘cloak and dagger’ style discussions.

We don’t recommend Decrypto in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

Decrypto contains no human art at all and as such it doesn’t have an issue with representation. It represents nothing except abstraction. The manual is presented in the second person perspective and makes no assumption of gender in the language. Example rounds make use of Alice and Bob as player names which gets kudos both for gender balance and for being an excellent in-joke.

Decrypto has an RRP of around £17 and it’s hard to fault at that price point. It comes packed with a huge amount of replayability and cleanly supports large play groups. My main concern here is not to do with repeated plays in terms of fun, but rather that the combination cards are somewhat limited – only twenty four combinations are available and they all follow the same pattern of ‘A sequence of numbers, one to four, with none repeating’. The more games you play, the more the percentages of random guessing are going to make themselves evident. It’s not going to seriously tarnish the game for anyone but it is a factor and if you were finding it frustrating there’s nothing to stop you making up your own code combinations. 2.4.4.1.2. Good luck.

We strongly recommend Decrypto in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

If a visual impairment intersects with a communication impairment this is possibly to be a problematic game – it relies on communication of clues being verbal or written and if neither of those are possible there are limited options to compensate. For those with a physical impairment intersecting with a communication impairment we can also see the encryptor role becoming difficult to action.

Indeed, the encryptor in general is the role that is most likely to represent an intersectional problem considering how it’s the only one with truly unique hidden information. In the normal course of play we might expect to see the encryptor role rotating around the table. For convenience, flow and playability’s sake though it might not be entirely convenient.

Other than this, Decrypto plays reasonably quickly and takes up relatively little table-space. It’s quick to setup, barring accessibility difficulties, and doesn’t seem like a candidate for exacerbating issues of discomfort and distress.

Conclusion

Well, it turns out Decrypto doesn’t do too badly here – perhaps not quite a strong enough performance to really make it a a tip-top accessible game but certainly one that doesn’t look like a dubious prospect for most game nights.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | A |

| Visual Accessibility | B |

| Fluid Intelligence | D |

| Memory | B |

| Physical Accessibility | B |

| Emotional Accessibility | A |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | A |

| Communication | D |

And that’s great because it is such a low cost game to bring out at a gathering that it’s wonderful that so many people are likely to be able to play it. Codenames is probably a safer bet as far as its teardown goes but it’s important to note that Codenames also requires a bit more setup and use of external tools to really be a good accessible game. Decrypto’s performance is without the use of steroids, and that’s not something at which we should sniff.

We like Decrypto a lot – four stars of like. I operate a one-in-one-out policy for my collection now and Decrypto sent Codenames off to the dark interior of a forgotten cupboard ready to be traded away to a more accommodating soul. While it does add some complications onto the simpler elegance of Codenames, the result is a reasonably accessible and immensely enjoyable game that definitely deserves your consideration.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.