| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Concordia (2013) |

| Accessibility Report | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.99] |

| BGG Rank | 24 [8.09] |

| Player Count | 2-5 |

| Designer(s) | Mac Gerdts |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

You might be forgiven for thinking Concordia is a Roman themed zombie apocalypse game, given the cover.

GRAAARARAR

That poor woman – she has the dull, vacant stare of the recently dead. Her lips are crusted with dried blood and parted in a smile that is only a whisker away from a snarl. Look at the gentleman with whom she is transacting – can you see the fear in his eyes? He’s just realising his mistake. He brought a bale of silk to a zombie fight, and now he’s going to end up with his entrails shucked like spaghetti. She’s not making eye contact with him – she’s looking at us. The trader’s fate is sealed. He’s an afterthought. She’s staring over at us, because we’re next.

That’s not what Concordia is at all. It’s actually a timely game that plugs a surprisingly large gap in the thematic roster of tabletop titles. It’s about trading goods in the ancient Mediterran… no, come back! Seriously, come back. I know we’re not off to a great start here, but please – there’s something wonderful here if you just give it a chance. I know it hasn’t met you remotely half way in this – I need you to be the bigger person. Bigger than even the coffin-sized box this game comes in. I need you to indulge me, so that I can create the context within which the game can indulge you.

So, yes – it’s about trading goods in the… actually, no let me try this from a different angle. You’re already a proven flight risk.

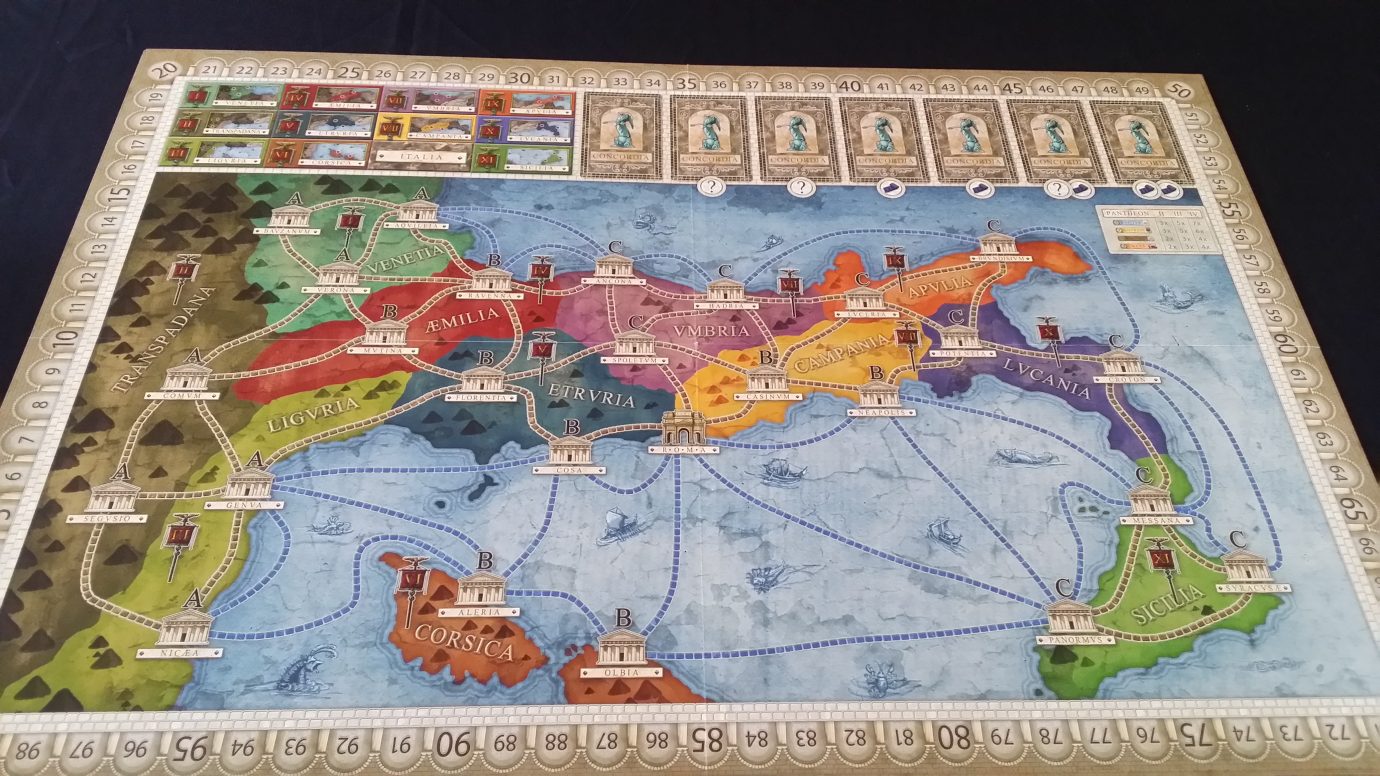

For all the dull vacuity of the cover, Concordia is a lovely game once you open the box. It’s got a big, high quality map that shows the Medit… that shows the parts of the world you’ll be battling over. It’s picked out in all kinds of deep, rich colours and swirling, mysterious lines.

This may be the first time anyone has made a board game about trading in ancient Europe.

And then, when you flip the board over – there’s another map! I love it so much when games do this. You get to choose your battleground, right at the very start! Do you want the open expanses of the Roman empire? Or would you prefer the tight claustrophobia implied by the insular city-states of ancient Italia?

Molto Bene!

And then you get the game rules, and they’re pleasingly succinct! You get a quick-start guide that tells you how to setup up the map, and you get a four page rule-book that explains all the minutiae of play. And for some reason, you also get a little pamphlet explaining the historical context of the time. I’m sure it’s all very interesting, but I instantly put it aside and never looked at it again. I’m very much hoping there isn’t a test at any point because I am absolutely not prepared to pass it.

You get a handful of mysterious tokens showing all kinds of exotic goods and rich, ancient spices. Except there aren’t any spices and nothing looks very exotic:

Goods, glorious goods

These are double sided, showing some coinage on the back and the goods themselves on the front. There are five of these, and they’re the main driver of success in the ancient Med… in the game.

In Concordia – first you get the wine, then you get – I’m not sure, I always get stuck at wine.

You get a pile of city chits, marked with letters on the back and a type of good on the front. They’re going to be used at some point to set up the starting game state. Your entire life, for the next two or so hours, is going to be dominated by these little buggers. They are going to be more important to you than your own children, assuming you have any.

Easy as I, II, III, IV

Each of the letters correspond to a type of city on the map:

There are big Ds on these cities, just like in real life

We’re going to be shuffling these, and playing them face down on the cities with the matching letters. Different provinces in the map have different letters they contain within their borders allowing the game an opportunity to meaningfully slant the value and weight of cities each time we setup the board. Isn’t that clever? Concordia is very clever. The end result is the world’s least interesting game of Scrabble:

I’m not sure Aabadda is a valid Scrabble word

When we’ve dealt out all the tokens, we flip them over and here’s where it starts to get interesting. What we’ve just dealt the table is a logic puzzle of logistics. That board is now a deep and absorbing challenge in the assessment and manipulating and mastering of supply and production. It’s going to be our job to take command of these cities and turn them to our bidding.

Ta-da!

The cities in a province each provide a good, and each of those goods has a value. Silk is the most valuable, and bricks are the least. However, that’s only a value in terms of money – everything in Concordia is worth having, and you’ll never have enough of anything to be able to relax. Once we’ve revealed the goods, we need to work out which is the most valuable good that is produced in a province. This becomes a ‘province bonus’ that we set up at the top of the map. These are the mouth-wateringly delicious treats we get for engaging in the civic-spirited act of bullying provinces for tribute.

I believe the goods are to scale.

Italia produces silk, wine and tools – a bale of silk is seven sestertii, a pitcher of wine is six, and a… uh… anvil of tools is five. The province bonus for Italia becomes silk. We take the little goods token we saw earlier, and assign to each of the slots a corresponding province bonus:

A rich selection of territories to exploit for tribute

And then we’re set up and ready to… sorry, no. Look, you’re being great – you’ve been very patient with a game that has so far done nothing to endear itself to anyone. I lied to you. We’re not done with setup yet. Set up, in Concordia, is a pain in the cornhole. They should have called the game Cornholeia. But I’m glad they didn’t, because I can’t imagine I would have bought that game and I’m very glad it’s available on my shelves.

The setup never ends

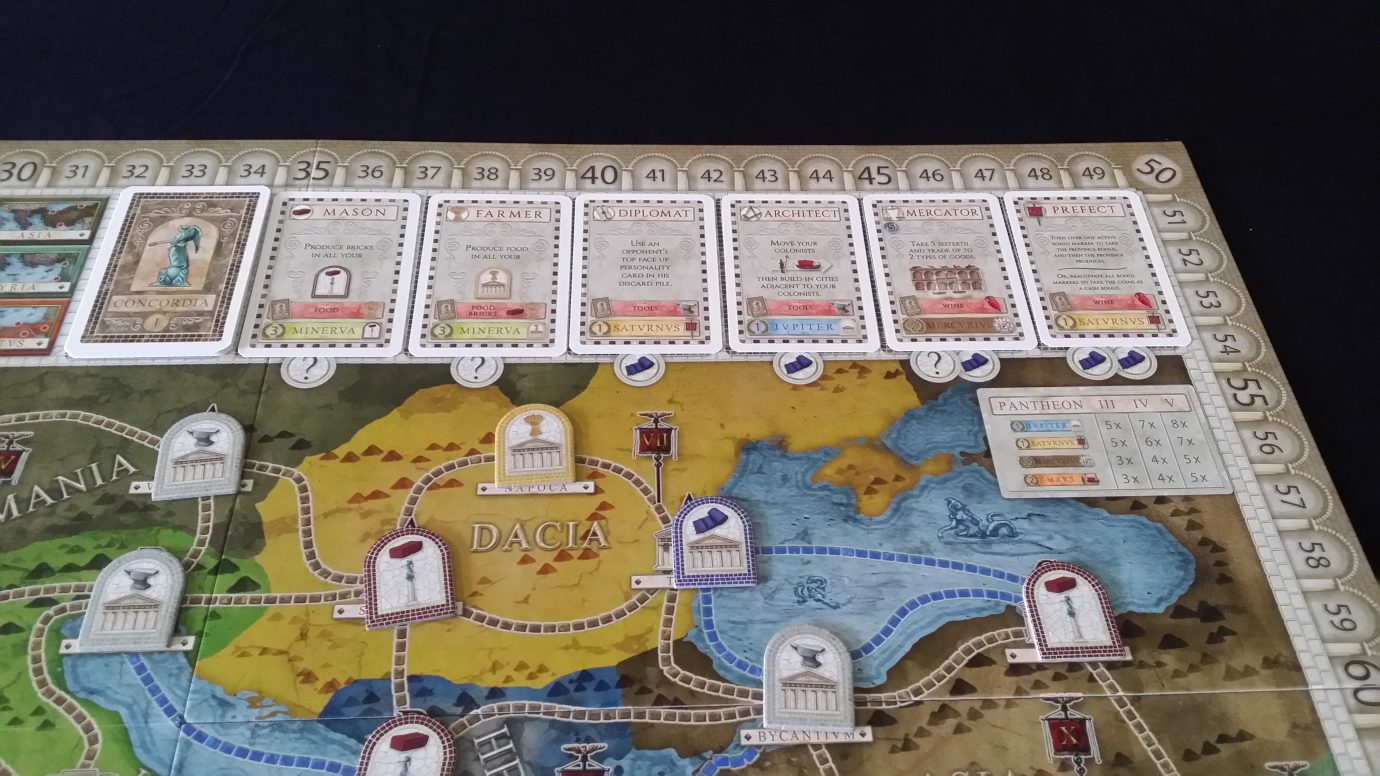

Next, we grab the decks of cards in the game. We have a coloured deck for each player, and then a series of decks marked with Roman numerals. We also have some reference cards, and a ‘Prefectus Magnus’ card – we’ll come back to that one. There are five decks marked with numerals – we only use enough of these to match the number of players we have. For two players, we use decks I and II. The reference card we get is two sided, and is a quick guide to scoring and spending. Honestly. Those are the ones in the middle of the top row. I know the reference card looks like a passive aggressive shopping list from the stern-faced bursar of a Roman temple, but this is the key to the core of the game. If you can unlock its secrets, you’ll be rewarded for your diligence.

We take our two numeral decks, and place the I on top of the II. We then place these at the top of the board, to the side of our provinces. We then deal out, from the top, six cards along the ‘personality track’. (ed – actually, you deal out seven cards and put the stack outside the board. Someone sent me a correction on that because we’ve been playing that wrong. And that someone was the designer. So – that’s embarassing!):

Power and influence

And here is where we’re starting to get to the interesting part. Each of those cards is an action you can do in the game – you take the card, play it down, and follow the instructions on the front. The coloured deck we took has seven cards in it, and these are also actions we can play. Essentially the top is a marketplace where we can buy expanded agency within gameplay. It’s simultaneously a way to create our own opportunity and the ability to make best use of the opportunities that other create.

BUT!

These cards are also the things that are going to decide victory, because each is a multiplier on the end of game scoring. See how they each mention a Roman god along the bottom? That’s the scoring track to which they refer. As you pick them up, you’re going to alter the way in which the game is scored for you – and because there are only a limited number of cards, you’re going to change the scoring landscape for everyone as a result. And once the cards are gone? The game is over. It’s very, very clever. Not only this, they also act as an accelerant on the game pace – people buy cards leisurely as they become affordable throughout the session. At one point everyone looks over and sees how few are left. The game instantly transforms from one of careful supply management into something more akin to the last scenes of the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

These are the tools you must master

Everyone gets the same starting hand of cards – a series of options we have for progressing in the game. These let us buy cards from the track above, enact trades, and claim cities. Every time we play a card, we place it face up in front of us and we can’t play it again. Except, we can, making use of one of my absolute favourite game mechanics. But let’s not spoil our appetite! We’ll talk about the tribune card later. It’s so magical!

So, how do we buy cards? How do we claim cities? How do we do anything? Well, we do it with goods. Concordia’s rather dour demeanour takes a turn for the sunny here because it provides us with a heap of fantastic tokens to represent each of the trade goods we’ll accumulate:

Senator, with these tokens you are truly spoiling us

How awesome is that? The bricks look like bricks! The tools look like anvils! The wine looks like pitchers! No mere cardboard tokens here – instead we get lovingly presented skeuomorphic things we can pick up and play with. God, I love Concordia so much.

Each player starts off with a warehouse of supplies – two food, one silk, one wine, one brick and one tool. And we also start off, disturbingly, with four settlers in our warehouse. I don’t know why they’re in the warehouse. I DON’T KNOW AND I’M SCARED TO ASK.

You should see what I keep in my cellar.

We also start off with fifteen little houses, raising distressing memories of endless hours spend looping a board of horrors in Monopoly. These though belong only to us – every player gets their own supply. Once they’re gone, the game is over. Concordia ends when someone empties the communal supply of cards, or their own supply of houses. Each player also starts with a small sum of money. The first player gets five sestertii (that is so fun to say. I love Concordia). The next gets six, and then seven, and so on.

I like to imagine meeple swimming in this like little board-game Scrooge McDucks

The last player also gets the Prefectus Magnus card, which passes to the previous player every time it’s used. It’s powerful, but also temporary. To take advantage of the card is to pass its weight and majesty onto your opponents. Black is going to start our game, so red gets that card

And now! Finally! Now you’re ready to play! I know I’ve lied about that already, but it’s true this time. Black decides to play his architect card.

Just the person to plan my extension

See, we have settlers in our warehouse – but we also get two on the board. We get a land settler, and a sea settler. Each can use different routes through the game. Everyone begins in Rome, and then population pressures will force them out into the wider world. Our settlers can build in any city to which they are adjacent, and it’s the routes they take, not the cities, that determine what adjacency means.

Rome is lovely this time of year

Every time we play an architect card, we get a movement budget equal to the number of settlers we have in play. We can then move our settlers, in any order and with any distribution of points, along the paths that are valid for them. Land settlers follow the brown paths, sea settlers follow the blue paths. We move into the centre of a route each time, connecting us between two cities. Black decides to move each settler one space each:

Autobots, roll out!

Once the movement phase has ended, the building phase begins. That’s where our little reference card comes in – it tells us how much we need to spend in order to build in any given city. Black’s land settler is adjacent to a silk producing city and he decides to build a house there. At the bottom of the card we see the eye-watering cost of that – we need to spend a brick, a bale of silk, and five sestertii. Ooft. Silk though is very valuable, and it can easily fund a campaign of procurement and influence throughout the entire world if we let it. We want to have an easy supply of silk, and buying a house in a silk-producing city is an easy way to guarantee it.

It’s a buy to let

The goods and money come from our warehouse, and are then discarded back into the common supply. We’re always going to need brick to build, unless we’re looking to build in a brick city. In that case, we need only a food. Bricks are the foundation, literally, of property management in the game. We began with one, spent it, and now we couldn’t build another city on our turn even if we could otherwise afford it. Our architect card is done, and discarded in front of us. We don’t have it any more. How do we get it back? JUST WAIT. IT’S SO GOOD.

Red then decides to play an architect of her own, moving her ship to Massilia and her land settler to Syracuse. Massilia produces brick, so it’s a food and one sestertii to claim. Syracuse produces wine, so it’s a wine, a brick and four sestertii. Both cities can be claimed in the one turn, which is pretty wizard. If we have the funds, and if we have the goods, we can build as often as we like in any unclaimed city adjacent to a settler. We only ever get to buy one house in a city, although others can come in later and muscle their way into our territory at increased financial cost..

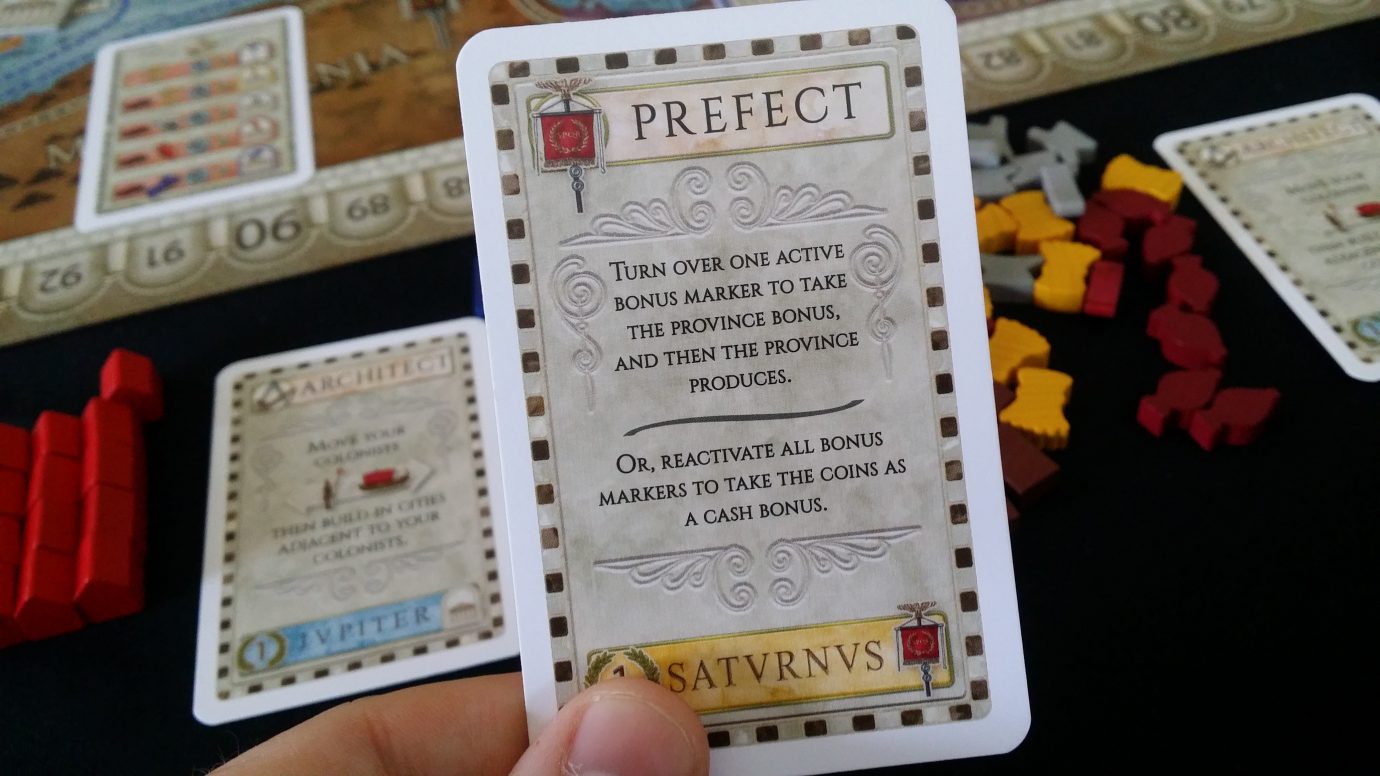

Black then decides to play his prefect card.

Nnneeeeerrrrrd!

Remember those province bonuses we saw earlier? This is where they start to matter. Black points to a province and says ‘I claim the goods in here’, at which point every building in every related city produces its indicated good for its owner. The player that put down the prefect card, and only that player, *also* gets the province bonus. Black plays the prefect in Italia:

So soft against my skin

The token is flipped over to its reverse – now nobody else can enact a prefect in Italia.

Cha-ching!

What do those coins mean? We’ll find out!

Black has a silk producing city in Italia, and so collects the silk from that city *and* the silk from the province bonus. Two silk bales make their way into his warehouse in a pleasingly profitable manner. Red decides to also play a prefect, this time in Gallia. Gallia has a wine bonus, and Red has a brick producing city within the province. A pitcher of wine and a pallet of bricks make their way into her warehouse. The goods must flow.

Black plays a mercator – this opens up a trading opportunity.

Heading to the Roman equivalent of Lidl

Playing the card instantly earns 3 sestertii, but it also means that black can trade goods. He can trade as many as he likes, subject to warehouse space, but only trade in two different *kinds* at a time. So he can choose to buy two kinds of goods, or sell two kinds of goods, or buy one and sell one. Black, feeling cloth rich, sells a bale of silk for a hefty seven sestertii, and uses that money to buy two bricks for six. Another sestertius in change from the transaction makes its way into his warehouse. Red now decides it’s time to make progress towards victory, and towards beefing up her deck for future activities. She plays her senator, allowing her to buy two cards from the personality card track:

Get your snout in the trough

Cards though are pricey – they’re bought in exchange for goods, and become more expensive the farther to the right we look.

Pork-barrel politics

Each of these cards has a good listed on the front – mason requires a tool, and farmer requires a food and a brick. In addition, they also cost a little extra – the question mark below means ‘as well as a good of your choice’. The silk symbol means ”the diplomat costs tools and a bale of silk’. The costs become punishing as our eyes drift off towards the edge of the board. When cards are bought, they are replaced from the stack. We fill up the gap that was created by moving all the cards to the nearest empty space on the left. We then fill up the new spaces with cards from the deck. As a result, cards tend to become cheaper as time goes on – and the new, highly desirable virgin cards cost an arm and a leg. Red decides to buy a diplomat, spending a silk and a tool to do it. That card is instantly taken into her hand, and is immediately available for play on the next turn. She can only afford one card, although the Senator allows her to buy two. One is enough for now though – once she’s taken the card, we shift the others down and reveal the next for sale. It’s a smith, for the poverty inducing cost of a tool, a brick, and two bales of silk. Ooft.

Black thinks ‘Oh, we’re doing the race to victory already, eh?’ and plays his own senator. He buys a mason and an architect. Two new cards then enter the track after we’ve shuffled the others down a space. They’re both colonists, which are cards that nobody has in their coloured deck. If we want those, we need to buy them from the personality track.

Pricey

Red plays another prefect, and plays it with the Prefectus Magnus card:

Squeeze the blood out of the provinces

She plays it in Mavretania. She doesn’t have any cities there, but the card gives her twice the province bonus and she wants the tool that the province generates. She gets two tools for her effort and passes the Prefectus card on to black.

Black plays his diplomat card. This is another area where Concordia is deliciously clever – while buying cards puts them out of your opponent’s grasp, if they time their own play correct they can copy the action of a personality you just discarded. Diplomat allows black to act as if he played a prefect of his own:

Tee-hee!

He decides he wants the tool that Asia produces, and so flips that token and grabs the province bonus.

Each card we play is an inevitable limiting of future opportunity. Our hands dwindle, leaving us with few options that we’d really like to explore. Red has a mercator, but no goods worth selling. She has two diplomats, but Black just played a diplomat, and you can’t diplomat a diplomat. So red does the only other thing she can do, she plays her tribune.

Kick it up a notch with the spice weasel.

The tribune is the drumbeat of the game – it allows her to take all her previously played cards back into her hand, pays her some money for doing so, and lets her place a new colonist if she wants. The more cards she has played, the more money she gets. At every instance of the game, we have to balance the return on investment versus freedom of action versus what we needs against the opportunity cost that comes with playing down the tribune. It’s so clever! The game ebbs and flows to the rhythm of the tribunes – play them well and you’ll always have the tools you need to thrive. Play them too stingily and you’ll never be able to take advantage of the opportunities the board presents you. If you play them too readily though you’ll lose out on income, and have to take the hefty cost of inactivity that the card charges.

The tribune card also allows for a new colonist to be placed at the cost of a food and a tool. This colonist always begins in Rome, and it’s usually a good idea to take advantage of the opportunity – if nothing else, it frees up some warehouse space. I DON’T KNOW WHY WE KEEP PEOPLE IN A WAREHOUSE WITH THE FOOD AND WINE AND… oh actually, maybe I just worked it out. As you were, Concordia, you’re doing God’s work there.

Black still has a prefect in hand, and plays it. This time, he makes use of the second action the prefect offers. After a few rounds, the province chart tends to look a little bare:

Pocket money for prefects

The alternative action of a prefect is to claim the coins shown, and flip the tokens over to their goods side. This makes the provinces available once more for exploitation. Seven sestertii is a pretty sum, and that flows into the black’s coffers with a delightful tinkle of cascading metal.

The more money on the province track, the more likely someone will claim it – but the longer you leave it, the richer the plum will be if you manage to pip someone else to the post. When do you claim the money? It’ll always be more financially sensible to wait, but if someone else blinks before you do you won’t get any of it. Oh god it’s so good it’s so good.

The game continues in this manner until the win condition is met, at which point the player that ended the game claims the Concordia card (and seven victory points) and everyone gets a final turn. And then we move on to the last stage of the game.

This is the world we made

Do you notice how I haven’t mentioned anything about scoring? Yeah, there’s a reason for that. We only do one round of scoring in Concordia, and we do it right at the very end. And nobody, NOBODY knows during the game how that is going to shake out. You might have a vague idea as to whether you’ve been playing in a way compatible with your own scoring setup, but there’s so much to do and so much to take into account that you’ll be lucky if you can even ballpark it. Good luck keeping track of how it’s worked for everyone else. That makes scoring in Concordia entirely revelatory – absolutely anyone can win it and so everyone has an incentive to keep plugging away at their mercantile empires until the final whistle blows.

Unfortunately, scoring is very clunky and requires a whole arithmetic mini-game of its own. First of all, all the cards in our hands are separated out into which God they serve:

A hand of red

Red has three Mercurius cards, four Saturnus cards, four Jupiter cards, one Mars card, one Vesta card, and two Minerva cards.

Black, like my heart

Black has one Vesta, one Mercurius, three Minerva, three Saturnus, three Mars, and three Jupiter.

Each of those Gods is scored differently, and the number of cards you have acts as a multiplier on the final score you get. When buying cards from the personality track you need to take into account not just what you need for immediate benefit, but what it’s going to mean for your scoring. Sometimes it’s worth buying a bad card just to solidify a victory point advantage.

ARE YOU NOT ENTERTAINED?

Let’s take it God by God, and see how our players fared. They don’t know how they did. They don’t know how each other did. I don’t know how they did. It’s a mystery to everyone.

The easiest God to deal with is Vesta – we sum up the value of all the goods in the storehouse, and add that to the cash total. Divide that by ten, and you get that many victory points. The collection of goods and cash that Red has gives a total of 79 sestertii, which become seven victory points. Black has a total of 77 sestertii in goods and cash, which is also seven victory points.

Jupiter grants a victory point for each house inside a non-brick city. That’s seven for red, and nine for black. But Red has four Jupiter cards, and black only has three. Red gets 4 x 7 (28) points, and black gets 3 x 9 (27) points. Brick drives city building, but if you focus on that to the exclusion of other resources you may find it difficult to expand into other cities elsewhere.

Saturnus grants a victory point for every province which contains at least one house. That’s eight for red, and six for black. Doubling down in a region gives greater prefect bonuses, but it does limit your ability to spread out over the map. Red has four Saturnus cards, and black has three. Red gets 8 x 4 (32) and black gets 6 x 3 (18).

Mercurius grants 2 VP per type of good produced – red doesn’t produce any silk, so only gets eight. Black produces all five, so gets ten. Red has three Mecurius cards though, so gets twenty-four points in total. Black, for all his diligence in diversifying the supply, gets only ten.

Mars grants two victory points per colonist you managed to get on the board. Red managed all six, for twelve points. Black managed only five, for ten. Red only has one Mars card though (for a total of twelve victory points) and black has three for a total of thirty.

Finally, Minerva – each Minerva card also has a good type on it, and for each city you control of that type you get the listed number of points per applicable card. Red get four points for every wine city, and five for every silk. She only has two wine cities, and thus gets eight points. Black gets three for every tool, three for every brick, and three for every food. Four tool cities gets twelve points, one brick city gets three points, and one food city gets three, for a total of eighteen points.

And then finally we add all of that together – red gets 109 points, and black has 110. But red was the one that ended the game by buying the last card, which got her the seven point Concordia bonus. So red wins with 116 points to 110.

God, I know I made that sound awful, and it does involve a fair bit of the same kind of arithmetic for which I lambasted Sheriff of Nottingham. It manages though to turn scoring into something that is almost impossible to unpick as you are playing making the final revelation excitingly tense. It keeps everyone in, and everyone invested, right up to the final conclusion. Sure, I would have liked that same effect without quite so much peering at the board as if you were reading the fortune in its entrails. I’m not sure what mechanism would have permitted that given the breadth of valid scoring strategies. In the end, the process of totting up cities and supplies and goods and resources perhaps even benefits from its intensity. The slow, ponderous accumulation of points and the swapping of leader positions has all the drama of a good sports match. Probably. I don’t really watch sports.

So, what exactly is it about Concordia that makes me love it? After all, just because a game is clever, it doesn’t mean it’s also fun – in fact, the opposite is often true. And Concordia is very, very clever. The need to carefully balance your hand and weigh up each opportunity in terms of how it impacts you and how it enables your opponents adds a wonderful depth to very simple mechanics. You’re constantly thinking about what to hold in reserve and when it’s sensible to take the hit for refreshing. You’re weighing up the cost of cards, which is considerable, against the victory point implications they represent. In buying cards, you deprive yourself of the resources to build in cities to produce further resources – when does it make sense to do that? You’re trying, and usually failing, to divine some kind of deeper strategy in how your opponents played based on cards they have purchased and the actions they’re taking.

Perhaps the most compelling thing about the game is the shape of play, which begins tight and constrained by both logistics of movement (settlers can’t share a route) and the restricted card economy you have available. As you purchase cards and get your settlers moving, more opportunities come your way and it becomes a case of choosing between multiple viable strategies. And then, as the game totters into the end-state, it constricts again – space becomes punishingly rare, and the cost to build becomes prohibitively expensive. Multiple players can build in a city, but the financial cost increases each time. Everyone is competing over vanishingly rare resources as they eye up the diminishing card track, count up the houses other players have left to place, and puzzle over the rough area in which their own score is going to land. And then just when the game threatens to drag on, the pace shifts up a gear when someone notices how few cards are on the track, or how few houses another player has. The final turns are an uncontrolled plummet, hurtling towards the end as players scrabble to grab cards and place cities before the time runs out. That in turn spurs everyone else on to mad acquisition – every single turn shifts up another gear. Everyone is mentally screaming in terror at the fast approaching finale that’s going to crush them into paste.

That would normally make for a very competitive game, but Concordia also adopts a generously collegiate approach to its game systems. When you prefect a province, everyone that has built there gets the resources. You’re not stealing resources away from them, you’re just beating them to the cherry of the province bonus. When you play a rare card you bought from the personality track at exorbitant cost, you’re also opening up an opportunity for diplomats to benefit from your largess. You can’t lock up markets, you can’t deny access to resources, and while you can drive up the cost of expansion you can’t actually stop it. It’s a game that manages to walk a tricky line between offering meaningful competition whilst also enabling largely frustration-free gameplay.

It’s a game too that permits meaningful expertise to evolve. Sure, it’s difficult to work out what your score will be while playing, but it’s easy to influence it through careful card choice and aim a strategy towards what’s going to yield you the greatest points. You can honour the gods you have in your hand, and they’ll see you right. You don’t *have* to do that though – you can just do what feels sensible at the time, building what you want and enjoying the satisfaction that comes from developing an effective economic engine. You’ll get points for everything you do anyway, so don’t let optimisation define you. This kind of design allows for novices and experts to play meaningfully together without the latter necessarily absolutely shellacking the former, and it’s a tricky thing to successfully pull off.

There are several interlocking logic puzzles in the game, and each of them is satisfying in and of itself. Optimal settler management involves weighing up the logistics of routes versus the budget you have for movement and building. Optimal deck management involves careful assessment of the value of cards at any given time, against the cards your opponents likely have available and ready to play. Do you want to diplomat a prefect, or would you rather wait for one of the unique cards that you don’t otherwise have in your deck? Someone just played their tribune – do you want to hold out for their architect so you get a chance to build before you reset your own deck? Production and management of goods too is a balancing act between the need to reset the board and the benefit you’ll give to everyone else as a result. Every time you prefect in a province, you give resources to anyone wise enough to build there. When is that going to be sufficiently in your benefit to warrant the advantage you give your opponents? When you have the Prefectus Magnus card, should you play it? What will your opponents do when they get it? Save it or spend it?

To be clear, this isn’t a game where a whole pile of things have been thrown together in the hope that through some kind of accidental ludic alchemy they transmute to gold. Every part of the game fits perfectly into every other part. There’s nothing, save for the end of game scoring, which seems forced or out of place. Meaningful play requires a lot of thought and consideration, and decisions you take early in the many different puzzles will eventually seamlessly converge as you head into the end-game. It’s a game that is elegantly and coherently designed into something that ticks over with all the precision of a fine Swiss watch.

I love Concordia to bits, and I think you will too. Absolutely recommended.

Errata

The designer was kind enough to get in touch about the review, and as I mentioned above he provided a correction to the rule. It doesn’t change what I think about the game, but it does change the game a little from what I have explained here. The game impact is that you choose between seven cards, not six, on the personality track. And the first card available costs only its face value, without any additional goods.

It’s clearly written in the setup, but I managed to miss it. The board just looked right the way I set it up. It’s totally an error on my part though, not in the game rules.