Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Chinatown (1999) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [2.24] |

| BGG Rank | 359 [7.43] |

| Player Count (recommended) | 3-5 (4-5) |

| Designer(s) | Karsten Hartwig |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

We’ve finally found a game that warrants our coveted (I assume, on the basis of no real evidence) five-star rating. Of the 155 games or so we’ve written reviews for here on Meeple Like Us, this is the absolute best of them. Seriously, while Chinatown is not a flawless game it is so good that I couldn’t talk myself down from the score. That’s even though I think the whole idea of a ‘perfect rating’ is utter nonsense. It really is that good.

Chinatown though is a game about business, and there’s always a trade-off when interests compete. I suspect we’ll have a great deal less of positivity to send your way in this accessibility teardown. Still, you never know – let’s do a business.

Let’s do all the business.

Colour Blindness

The individual player markers are yellow, green, red, purple and white. This is occasionally going to be a problem, depending on how many different kinds of colour blindness must be taken into account and the number of players involved.

There are quite a lot of these markers, but realistically all they do is indicate ownership of a lot and as such they can be easily replaced with cubes, coins or any number of other tokens if necessary. For those with less severe symptoms, it might not even be an issue at all

When it is an issue it’s going to be significant because knowing who owns which properties, lots and the connection between them is incredibly important in the horse-trading portion of the game. Consider the Protanopia view above – a player might well think that one player has four lots together (a huge game advantage) whereas it’s two players, each with independent and unconnected lots. The way you approach one deal will be very different from the way you approach another even if you pick the right player with which to negotiate.

To be fair, there’s not much lost if you inquire of the table since all deals are made in public anyway and you won’t direct any attention to a lot by asking its ownership in a way you wouldn’t by simply trying to negotiate. It will though have an impact on game flow and may obscure some potential opportunities simply because they don’t manifest in a way that is visually distinct.

Other than this, the game is fully accessible even if I’s not entirely easy to parse complex game state at a distance. The lot cards carry no colour information, but shop tiles make use of colour to accentuate their distinctiveness. Seeing each business colour-coded can help contextualise the risks, rewards, and opportunities of trade. Mixing them up can undermine those efforts.

Close inspection will reveal the state of the board because each tile has a unique icon and written text but it’s going to be easy to miss subtleties. For example, a player with Protanopia might mistake two takeout tiles next to a seafood stall as being one contiguous chunk of three tiles – especially if shop tokens and ownership of tiles are ambigious.

We’ll tentatively recommend Chinatown in this category, but some compensations and careful consideration of board state are going to be needed.

Visual Accessibility

Visual accessibility is predictably poor – the game state sprawls, is highly interrelated and often comprises of tiny tiles nestled up against other tiny tiles with small tokens to indicate ownership. Aside from placed tiles and the status of a lot being owned or otherwise the game board is highly febrile. It will change dramatically over the course of turns as deals are made and unmade. Knowing how the board is going to change relies not only on seeing where people can make deals but also tracking that with regards to the deals they are actually talking about. If you want to keep ahead of the momentum of the game, you need to be planning for the deals that are about to be completed.

The game state in front of each player is relatively straightforward – some tiles which can be closely inspected and some money. The money is card, and there is no distinction made between different denominations other than a change in the number and the president on the front. That can sort of be solved through adopting an accessible currency but either that needs to be used by everyone or it has to be compatible with the need for the total sums people possess to be secret. That’s a difficult combination of things to insist on without the use of an additional aid like player screens. Otherwise approaches such as the folding method or the employment of standard currencies won’t be at all appropriate. They give too many clues to players as to the accumulated wealth of everyone around the table.

Most of the game is found in the discussion between players rather than on the board, but the problem there is that these discussions rely on insights gleaned from the board. You want to identify not just where you have something someone else wants but also where you have something that you don’t want but can trade with a third party for something another might like. That means you need to know the shop tiles that each player has in front of them as well as the lots on the board. That’s possible to remember, but then you also need to consider how unplaced shop tiles in every player’s hand might relate to the properties everyone has on the board. As usual, if a totally blind or visually impaired player really wants to play Chinatown it’ll be possible. I suspect though it’s likely to be so difficult as to take all the fun and energy out of it.

Part of the problem too is that shop tiles aren’t necessarily very visually distinct and the contrast is occasionally poor – it’s easy to mix them up at a distance and even sometimes when you’re inspecting them closely. The florist and the tropical fish for example don’t have a lot to tell them apart if visual impairment must be considered. Most of the time though you won’t be looking at them close up – you’ll be trying to assess their value and impact at a distance. You don’t lose much by inquiring of the table but it will add a burdensome chore to every deal you weigh up in your mind.

We don’t recommend Chinatown in this category.

Cognitive Accessibility

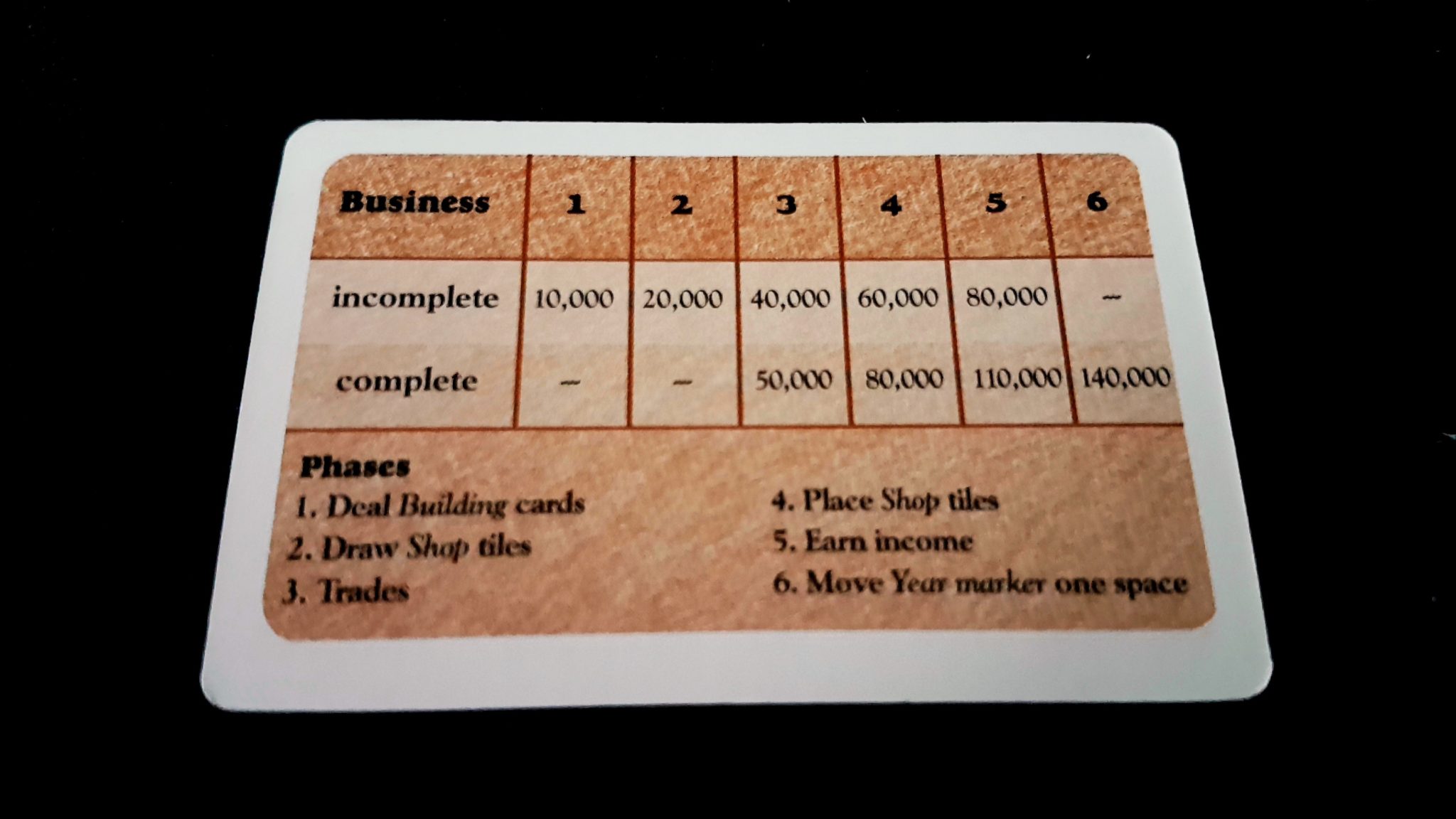

Unsurprisingly a big nope here. The need for numeracy is not just extreme – it is pathological and it’s very easy for even those confident with the arithmetic to make mistakes because it’s often segmented. For example, the difference between you selling me a tile and a lot is not $0 and $110k. It’s between the placement I can make without your support and the placement I can make with it. If we’re discussing trading two lots, then it’s about what I can get with one versus what I can get with two, versus what I can get with a different deal someone else might make. It also compounds over turns – $50k a turn means more in round one than it does in round six. And on top of that, your money is also your score so any advantage you confer on another player in a deal is straight up going to put your further away from victory.

A deal then essentially becomes ‘What it costs me now, over what I can get by making the deal, minus what I get without making the deal, in comparison to what they get out of the deal over the number of turns we have left’. You’ll be making several deals per turn and they’re all structured like this. Often you will be contending with other players making counter offers and muddying the waters. ‘Yeah, it might work out to $50k in your favour but look – it’s next to three other open lots and that means you might get a big block for nothing in the next draw and I think that needs to be factored in’. You’re often trying to ponder imponderables and compare incomparables. It’s challenging wall to wall.

Then on top of this comes an act of selling. It’s not enough to have a great deal you want to make – you have to convince people that they want it too. You have to pitch it. It’s perfectly possible that at any point someone will throw the negotiation equivalent of a live grenade into the discussion. You’re nickel and diming your way to a consensus on a deal and someone buts in and says ‘Tell you what, I’ll buy the tile that’s part of the deal for $50k’ and suddenly everything collapses. You need to be able to very quickly react to tell people why that deal is nonsense and yours is the superior offer. Nobody is going to be helping you here either – everyone is on their own because there are no friends in the free market.

The game state is very complex, very febrile, and very difficult to parse. There will be spaces that have all the rigidity of mountains – nobody will be able to make a deal to move them. There will be parts that are more amorphous. Your ability to accomplish great things might be dependent on making a mental juxtaposition that recontextualises the value of a square or offers a deal from an odd angle that nobody else considered. The smoothest talker will get their way here, and those that have a formal understanding of the game theory associated with negotiation are absolutely going to dominate until everyone catches on to their tricks. Real world knowledge can transfer into a skill advantage.

The game flow is reliable in that the actions taken are consistent, but essentially each trading round is a starter pistol on chaos. Nobody gets anything as well defined as a turn – you all negotiate at the same time. That’s going to lead to a lot of cognitive overhead as several deals may be underway simultaneously and any one player may be involved in several at once. Even if that’s not a player with cognitive impairments an important part of the game is following along with what’s being proposed so you can undercut or capitalize as is appropriate.

All of these are tasks that bridge our two standard categories of cognitive accessibility, but the game’s not done yet. It also requires money totals to be kept secret and while that can be house-ruled away it’s not a good idea because it’s an important part of self-regulation of the systems. People will likely have an idea of who is ahead but they’ll rarely be completely sure. The table will likely work to undercut the obvious leader and so knowing who that’s likely to be (and perhaps, having a better idea of who the real leader is) is immensely important in still being able to structure winning deals.

We don’t at all recommend Chinatown in either of our categories of cognitive accessibility.

Emotional Accessibility

Oof.

So – Chinatown is a game where players can absolutely swindle the Beejeezus out of each other and the victim might not even realise until it’s too late. The only rule in the trading is that anything goes and that means that if you have a certain kind of group emotional manipulation and blackmail might very well come into play. That’s not necessarily a negative thing if it’s part of the comedy of your social dynamic. My mother for example wields guilt like a fine blade in games like this but there’s never any malice in it. Let’s say though you have a deal that is perfect for someone you care about and they want to make it all about how much you care. Well – that’s a recipe for potential distress and it’s absolutely a thing that can and will happen. Again, whether it’s a problem depends on your group – it can be entertaining rather than emotional. It can though easily cut the other way.

Chinatown is a game about negotiation, and thus about communication, and often about communication under less than ideal circumstances and with less than forthright honesty. You want people to think they’re getting a good deal but you don’t necessarily want them to know how good a deal you’re getting in return. You want to throw a fog over the benefits to you while shining a spotlight on the benefits for them. Some bluffing and bluster will go a long way here, although it’s not strictly necessary. An honest horse-trader might make money, but it’s the dishonest one with a fast horse of their own that makes a killing. However, in some circumstances this might be a benefit – there’s nothing that kills someone else’s deal quite like an uninvolved party performing an autopsy on the balance sheets. Still, knowing when to hold them, when to fold them, and make people think you’re less interested (or more interested) in a deal – those are important skills in Chinatown. You need to have a considerable degree of emotional intelligence.

Score disparities can be significant, and there’s no real room to hide here. While there is some luck involved so much of the game is simply about talking people into deals. If you can’t do that – if you can’t parlay a sub-optimal opening into a profit – then the reason is you. For an explicitly social game, it’s because you couldn’t convince people. Why can’t you convince people? Well, it might just be you genuinely didn’t have anything to trade but it’s also easy to infer something negative about your personal relationships. There is artifice and deniability in here – the reason people are backstabbing each other is because of the game – but you know, what if? Maybe the reason you failed is because people don’t like you – maybe that’s why you had $100k when the winner had a cool million. Maybe.

And then on to that you layer the issue that you need to trade to get anywhere and if nobody trades with you it will sometimes be targeted. Everyone is incentivised to undercut everyone else and ruin their best deals. In the end Chinatown is a game where to pay money to one player is to deprive yourself of score. You want to make sure it’s as close to a zero-sum game for everyone else as is possible in an open economy. You may find yourself unable to make deals because everyone else actively and intentionally talks your trading partners out of it. In the end a score disparity might be because everyone, either through co-ordination or coincidence, talked everyone else into making you a pariah at the table. If you’re not involved in the trading, you’re also not involved in the game so there’s a sense of social isolation that can also come into play.

Now, I don’t want to overstate this – Chinatown is a game that also encourages a rational pragmatism and you’ll almost always have something you can trade even if you have to basically engineer its value yourself. There’s a spectrum of involvement here though from ‘involved in every deal’ to ‘only called upon when it’s to someone else’s advantage’. Where a player lies along that spectrum is likely to impact on how much fun, and personal satisfaction, they get from playing. I can imagine this being a very stressful game under certain circumstances and those circumstances don’t have to be malicious. Not everyone is going to have the same chance to play, and not everyone is going to have the same amount of engagement as a result. If you’re not comfortable basically throwing a deal out into the wild with confidence you may find your involvement in the game is incidental. Given that negotiations can also take a long time, you may spend an awful lot of the session simply listening to people play the game.

Placement of shop tiles is the only permanent action you take in the game, but while that means you can trade and wheedle away from some mistakes ultimately your ability to do so depends on how forgiving other players are. You can say to someone ‘Oh, sorry – I shouldn’t have traded that lot. Can we swap back?’. They might say though ‘Sure, for three times what you paid me’. Being unable to undo mistakes in any game can be deeply frustrating depending on the significance of the consequences. Here, you’re not so much unable to undo mistakes are you are explicitly denied that by someone’s choice. They can hold your mistakes to ransom, and they’ll be trying to cheat you out of things on a constant basis which makes it all doubly unpleasant.

Overall then, we don’t at all recommend Chinatown in this category. This is a game of naked capitalism, and capitalism is not a kind system.

Physical Accessibility

The board of Chinatown is incredibly easy to upset, although it’s also reasonably easy to reconstruct. The tiles you place are tiny and have to go in tight constraints, often underneath ownership markers. The act of placing a large building can make it easy to forget who owns what squares if you need to move stuff to do it. None of that need be done by a player with physical impairments though – it can be handled as a communal task of the table.

While there’s a lot of trading and swapping and collecting that goes into managing shop tiles there’s not much that has to be done independently. All tiles are drawn from a bag, but if everyone trusts everyone else to do that fairly (and why not?) all a player need do is check the tiles put in front of them. They’ll also need to check tiles in front of other people and that might be difficult with a large table given how small the tiles are – mostly though no game information, or at least no game information that isn’t already deducible, gets leaked by doing this.

Money needs to be tracked secretly, and that’s likely to be the most significant accessibility issue for the same reasons we discussed above – the cards are quite small, can be difficult to work with, and it’s not straightforward to replace them with an accessible version. The use of some kind of secret screen though would assist here, in which case poker chips or equivalents might be employed.

If these physical issues can be overcome, then the game is entirely one of negotiation and a physically impaired player is likely to have no difficulties in engaging with the game from all angles. All you need to manipulate is other people.

We’ll recommend Chinatown in this category. Just.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

Well…

Look, I don’t know if Chinatown is a racist game. It’s not for me to say. I will though say it is intensely stereotypical. The businesses you work with are things like laundries and takeaways and dim sum stores. If someone did a word association with ‘Chinese business’ you might expect a considerable overlap between the tile set here and the list generated by your prejudiced uncle. It gets remarked upon when people pass. To be fair, this edition of the game comes with 13 blank tiles you can use to put your own, less cliched, businesses into rotation but it seems like a poor fix. It seems weird and unsatisfying too to say ‘Product of a different time’ even if Chinatown was first released almost twenty years ago. This specific edition is from 2014, so you know – it wasn’t that different. I don’t think there’s malice here but I do think it’s a bit lazy. Similarly with the gender balance – the cover shows a man facing into the camera and two men and a woman heading into Chinatown itself. There isn’t a lot of gendered art but what’s here is skewed. The manual defaults to masculinity here as well. It’s just a bad combination of things.

As to cost, it’s a little complicated. This printing is very difficult to get and it’s not unusual to see second hand English copies floating around for anything between £50 to £100. I was lucky enough to get mine for £34 thanks to the kindness of David Wright over at Tabletop Scotland. He managed to find a new copy in my local game store. That was a little embarrassing considering I had gone to that local game store in the hope they had a copy but didn’t see it. So – it’s pricey because of its rarity. Even if you do find a copy it really requires four or five players to sing and that can be a difficult combination given the complexities of actually syncing up with people in busy lives. For Chinatown too, it depends on having a compatible mix of people that won’t take the aggressiveness of the trading too seriously.

There is though I hear a new version coming, or I wouldn’t have reviewed it. We’ll see whether that new printing addresses the issues outlined here. Until then, we don’t recommend Chinatown in this category but you know – stay tuned!

Communication

Another big fat nope here. While there isn’t much need for literacy there is an overwhelming need for communicative fluency under challenging circumstances. Those circumstances include people butting in, undermining deals, interrupting and distracting participants in a conversation and running deals in parallel. The sophistication of the persuasive case a player needs to construct is intense and often multi-parameter. It’s time constrained too – not specifically by the game but because any deal remains viable only as long as the lots and shops are in contention. You want to seal the deal before someone else comes along. Sometimes the value of your deal depends on making it before someone else completes theirs even if they are not explicitly connected.

It’s not enough here then to be able to convey an argument, but to be agile in adjusting it and refining it in light of the objections of your other deal-maker and in response to sabotage by other people. This is also something that’s often being done in parallel – multiple deals will almost always be under discussion at any one time and may involve some of the same people. Occasionally, some of the same lots and shops. Even the act of getting someone’s attention to make a counter offer might be challenging.

As we discussed in the section on emotional accessibility too, it’s important to be able to convincingly bluff, to mislead, to distract, and be responsive. You need to roll with some complex social dynamics and I just don’t see that being at all compatible with accessibility needs in this category.

We don’t at all recommend Chinatown here.

Intersectional Accessibility

The bad news is that the accessibility profile of Chinatown means that it’s likely unplayable by lots of people. The good news is that this section will be short – we recommend the game in so few categories that really intersections don’t matter. The sole exception would be if colour blindness intersects with a physical accessibility issue then the need for close examination might be sufficient to invalidate it in both of those categories as well.

Games of Chinatown last considerably longer than the hour playtime the box suggests, and every one of those minutes is intense and full of calculation and negotiation. It’s very likely to be a draining experience and it’s also one that offers no room for people to drop out. Too much is based on the impermanence of ownership that you can’t simply leave parts of the board unchanged without it being to the intense detriment of the game. You also can’t simply redistribute board components or return them to the decks – too much of what happened earlier was inspired by the board as it was for that to be fair or feasible. Those that start a game of Chinatown will need to finish it unless they can have someone tap in for them.

Also, Chinatown is an intensely competitive game that requires players mislead others as to the true value of the deals they make. I mean, it doesn’t technically need it but it’s hard to be an honest trader and make a profit. As such, players are incentivised not to correct mistakes people make as a result of accessibility compensations. For those categories where we recommend the game there are only a few times that might be a genuine problem, but it’s still something that might make a difference. As usual, play with people as interested in your fun as they are in their own.

Conclusion

Well, Chinatown achieves two distinctions here on Meeple Like Us. It’s our first game we rate as five out of five. Yay! It’s also now the holder of the title ‘least accessible game to date’. Boo! That undoubtedly comes as some relief to Unlock which had been granted that dubious honour under unfair conditions. It’s a close thing, but yeah. I guess actually that’s three distinctions, because it’s also ‘biggest differential from review to teardown’. It’s not surprising, but there you have it.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | C |

| Visual Accessibility | D- |

| Fluid Intelligence | E |

| Memory | E |

| Physical Accessibility | B- |

| Emotional Accessibility | E |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | D |

| Communication | E |

There is scope here for it to elevate itself though with the upcoming new edition – assuming it makes any changes to the aesthetics. A few tweaks to colour blindness, a bit more inclusiveness in the socioeconomics. Either of those would knock it out of the arse end of the scale but honestly not to the point we’d be likely to be too enthusiastic in any case. It’s a difficult, deep, marvelously intricate game and there’s a cost for that.

I hate to see a game this good be so inaccessible to so many people, but in the end it’s not up to me. I just work here. You got a problem with it, take it up with the manager. Chinatown is now the best board game I’ve ever played. The enthusiasm of my recommendation though gets tempered into almost nothing when faced with almost any person with almost any disability. Still, if you’re one of the few people that got a recommendation, and you find it out in the wild, you should absolutely snap it up. It is a glimmering, glinting jewel of a game.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.