Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | The Fox in the Forest (2017) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.58] |

| BGG Rank | 571 [7.11] |

| Player Count | 2 |

| Designer(s) | Joshua Buergel |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

I like the idea of the Fox in the Forest better than I like the game itself. It has to be admitted that might be because every time I try to remember what a trick-taking game involves all I can visualise is television static intercut with scenes from The Shining. More than is ever the case you should disregard my view in favour of anyone that knows anything. Literally anything. As a lecturer who regularly gets paid for teaching classes on subjects he doesn’t understand, that is damning self-criticism you should take seriously. Our review gave the game three stars, not that you should really care.

I’m on firmer ground here with a teardown though – at least there are some hooks Iupon which can hang my hat. Let’s beat some bushes and see what we find. If you go down to the woods today…

Colour Blindness

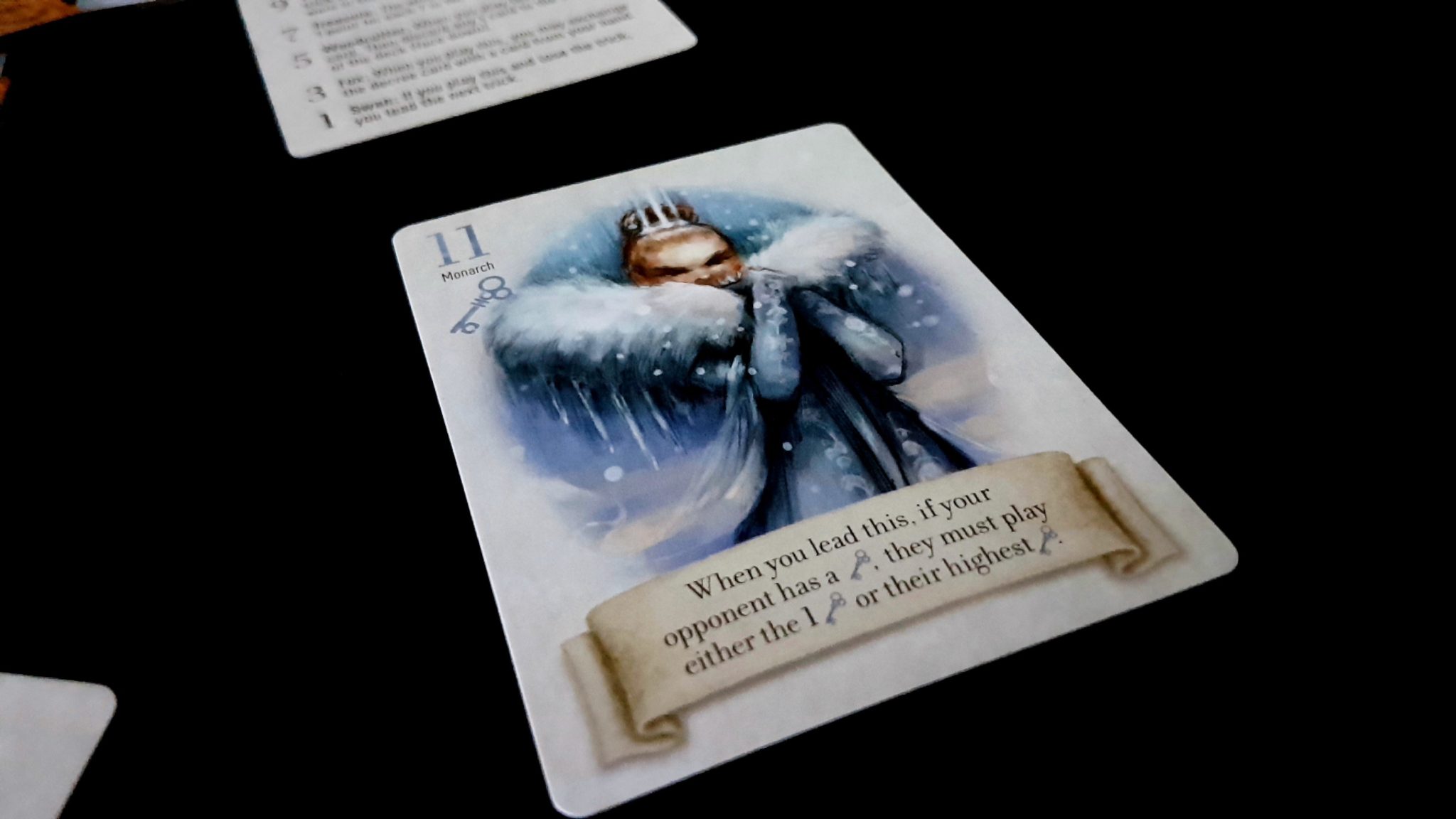

Colour blindness isn’t an issue with the Fox in the Forest – each suit has a different colour but it also has a clearly differentiated icon as well as unique art that offers its own clear hint as to its ownership because of the thematic link between each element.

For example, the key suit has a theme of winter and all the art is bound up in that. The moon and stars are wreathed in darkness, and there’s an ominious undertone to the art and the palette that conceptually links it together. It’s really nice – even those elements that don’t have art have the same clear differentiation as a pack of playing cards.

We’ll strongly recommend the Fox in the Forest in this category.

Visual Accessibility

Cards are well contrasted – the action text on each has a scrolled background that ensures readaibility against the text although the font is quite small and is occasionally interleaved with the symbols that indicate card suits. However, there are only a handful of special cards that have powers and they’ll soon be committed to memory – the text is an aide memoire rather than something critically state dependent. It’s a useful reminder but eventually it will become unnecessary.

Unfortunately the suit and number of each card is indicated only in one corner, and that means that orientation becomes important to curate. To begin with each player will have a total of thirteen cards and arranging the cards properly is going to be important when fanning them out or employing a card holder to ease play. A fair degree of in-hand management is going to be needed but on the positive side it’s comparatively rare that new cards will enter a player’s hand. Mostly they’re played out, but there are some exceptions with regards to special power cards that might be activated. In those circumstances, cards are swapped and the in-hand management required to accommodate that is likely to be limited.

Scoring tokens are used to indicate cumulative game state, and while these have different colours they also have some contrast problems and have no way of being differentiated by touch. Also, whether the highest denomination is a six or a nine is not really obvious from context. Probably a nine, but it’s really quite hard to tell. This needn’t be a significant problem since players can simply move to more accessible ways of recording scores – matchsticks, coins or poker chips would all be appropriate here as would someone writing it down. It only changes at the end of rounds and when a player collects up a ‘treasure’ card so this part of the game need not be too burdensome.

When collecting up a trick, a player wll take the two cards and add them to an empty part of the table. You need to record this because the number of tricks a player has is important information – this means that you can’t simply stack them up. Usually you’ll interleave them so they form links in a chain structure, but the easier that is for the other player to see the better. Asking is risky. There’s nothing more likely to throw cold water on a plan that involves overlooking a trick difference than asking how many they have.

Representing the game state otherwise is simply a case of verbalising the three cards that make up the moving parts of the game. One of these is a decree card, one is the leading card and the other is the card played to follow it. At most a player is going to need to know two of these since the other will be in their hand ready to be played.

That though introduces the key accessibility challenge in the game – relating cards in hand, of which there may be as many as thirteen, to the situation on the table and the tricks that have been gathered up. That’s a lot of possibilities that need to be considered, although at any time you’ll mostly be worried only about those that follow suit. For a player for whom total blindness must be considered, this seems like an insurmountable problem unless someone is available to verbalise what may be in their hand. For players with less severe visual impairments the question becomes ‘how much of a card can they see and how many of the cards can they easily see at once’. This become considerably easier to do as time goes by but may perhaps be a substantial problem in early phases of the game.

We’ll recommend, just, the Fox in the Forest in this category. This we do with the caveat that players will be, at least at the beginning of a round, be working with a substantial hidden hand of cards and they can’t disclose its makeup without influencing the game. Those for whom total blindness must be considered this game is roughly as inaccessible as any primarily card driven game is likely to be.

Cognitive Accessibility

I know that I’m not alone in this weird cultural blank-spot as far as trick taking goes, but I’m reluctant to label it an issue of cognitive accessibility. I think it’s just linked to the degree to which people internalise their own life experiences. If you grew up with classic card games you’re far more likely to have purchase on the concept in a way that can’t be relied upon for those of us who only had poker as the backdrop to our childhood. Nonetheless, the jargon of the game can be somewhat difficult to work with for some people. I played this up a degree in the review, but it’s an honest issue I face. I have similar issues whenever people refer to ‘melds’ in Rummy style games. I don’t even know what Rummy style games are. Some games are really only intellectually parseable in reference to their own internal definitions and I think that’s true here of the Fox in the Forest.

However, it’s not that the rules are complicated and you could bypass the whole sorry business entirely by not relating it to game categorisation. The leading player plays down a card. The following player has to play a card that matches suit – best card wins. If a player has no matching suit, they play down anything and the leader wins unless the following card was of the trump suit. The elasticity of the scoring structure though adds a complexity here because it creates a misalignment in assumption of incentive. You don’t want to win all the tricks – you want to win enough that you get you the most points, but that may occasionally need you to play to lose. If you think of the standard outcomes of any two player dyadic challenge, the difficulty isn’t winning. It’s getting the result you want which is usually, with our normal conception of games, the winning outcome. It’s as difficult to lose when both players want to lose as it is to win when both players want to win.

Coupled to this is the need for players to understand when they may want to switch from one strategy to another. If you only decide to play to win when you have been lumbered with four unwanted tricks you’ll likely find it very difficult to make up the difference by the time the round ends. If you decided to turn to winning earlier, it will be a much harder challenge because both players have equivalent goals. There’s a flexibility in card play that comes with the special powers that’s more like judo than it is a boxing match – it’s about playing the least valuable card that accomplishes the outcome you want while thinking ahead to what you’re going to need in the future. You need to conserve your resources.

The need for literacy is limited, but only because most of it eventually gets offloaded on to memory. Several cards in the deck have special powers and while there aren’t a lot of these it takes a degree of cognitive capacity to be able to effectively utilise them when it matters. None of them are extremely powerful but they can be the push at the exact right moment that gets the avalanche started. Their effects are relatively simple but it might be necessary to remind a player of their impact and it’s difficult to be proactive there. Each player has a hidden hand of cards, with varying complexity and applicability, and it’s not possible for someone involved in the game to give guidance without it impacting on game state. Numeracy requirements are lower, requiring only comparison and light arithmetic.

Game flow can be a little unintuitive since it’s the player that won the last trick that leads the next except in the case of some special cards that adjust that. The momentum of the game is very much with the leading player, and subverting this game flow when it’s advantageous is useful in regaining initiative. As such, game flow is important, changeable, and to a certain extent within the control of each player to cede or command. There’s a tug of war element here that needs to be taken into account with each play, because depending on your eventual goal you won’t always want to be the one setting the pace of the game.

There are some light synergies in card play with Fox in the Forest, but they aren’t the complex chains you would see in a deckbuilder or equivalent. They’re things like ‘Play this card to change the decree card so that you trump your opponent’ as opposed to ‘Play this to enable that, which then lets you do this three times which then…’. Perhaps more important here is for players to remember others may have the option, should they have the appropriate cards, to enact these kind of strategies. Remembering when powerful decree cards swap out, or when they’re spent in tricks, is partially a burden on memory.

Employing these well is useful, but it’s not vital for good play and you could play without the special cards if necessary. It would reduce the sophistication of the game, and thus its cognitive complexity. That would though certainly come at cost to how interesting it is to play.

With this in mind, we’ll tentatively recommend the Fox in the Forest in both of our categories of cognitive accessibility.

Emotional Accessibility

Everything bad that happens to you in the Fox in the Forest is likely to be your own fault. If you play to lose and end up with tricks you didn’t want that’s your reward for a risky strategy. However while the game gives you two key ways to win a round but it doesn’t necessarily give you the tools for accomplishing either. Occasionally you’ll be forced to make risky plays just because you didn’t get the cards you need for anything else. You play tourney style though with repeated rounds that each build up a point total so the impact of luck gets mitigated a little.

An interesting feature of the design here is that it gives players a lot of room for ambiguity in the meaning of ‘poor performance’. Failing to win a single trick is a great strategy because it forces a player into the ‘greedy’ scoring tier that nets them nothing. Losing every trick means that you even have some wiggle room if you start winning – you can dominate the game as long as you gain fewer than four tricks. So, let’s say you end up with four tricks – is that because you played poorly or because you played well but not quite well enough? It’s marvellously face-saving and another reason why I think this mechanism is wonderful. Score differentials here can be high, but that’s good because if one player was comprehensively dominated it was because they submitted to it. They wanted it. Or at least, they can argue that’s what they intended.

The special power cards you have available add a little bit of a take-that element to play, but they’re situational enough to be manageable and predictable enough to be preventable. And again, the fact that players may actually be trying to lose tricks can take the sting out of their employment.

We’ll recommend the Fox in the Forest in this category.

Physical Accessibility

There are a lot of cards in your initial hand – thirteen of them in fact – and this is likely to be enough to overwhelm a standard card holder. You’re likely to need a couple of these, although the hand you have to manage gets smaller as time goes by and tricks are played out. All you really need to see of each card is its face value and its suit, although the text reminders of card effects will be useful until they’re fully memorised. In any case, you have available a reference card that outlines their effect.

The game is otherwise playable with verbalisation – the effects are either deterministic or have decisions that can be equally easily indicated verbally The only slight complication here is in the collecting of tricks in a way that is easily counted by both players at the table. ‘Laddering’ or chaining cards is fine here.

We’ll recommend the Fox in the Forest in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

The art here is lovely, and each of the empowered cards has its own unique illustration. The publishers here have gone for a broadly inclusive roster that I’m pleased to see even if I think it could have drawn less heavily from white European ethnicities. Still, you’ve got men and women here in positions of power and authority including two queens and a king. Also bad-ass swans and foxes.

At the time of writing, the Fox in the Forest seems to be a little difficult to find. It has an RRP of £15, and really my honest question here would be – ‘Why is this better than any trick taking game you could play with a standard deck of cards?’. I genuinely don’t know the answer, this isn’t rhetorical. As I said in the introduction to this article, I am really a bad person here to comment on the worth and value of the game. It is only a two player game though, and that does limit the kind of circumstances under which it is a wise purchase.

We’ll recommend it in this category because there are no particular red flags, but think of that as a soft judgement born mostly out of ignorance.

Communication

There is a need for literacy in the short term, or at least for someone to be willing to explain card effects. There are sufficiently few of these, and with sufficiently low complexity, that their mechanics will soon be internalised. There is otherwise no need for communication in play. We recommend the Fox in the Forest in this category.

Intersectional accessibility

The Fox in the Forest is a two player game and that does impact on the arithmetic of accessibility. In a larger game you’re more likely to have abled players, or at least players abled in a particular category, who can enact instructions on behalf of another. Here, you’re reliant on one other person and that can make table support difficult. A visual impairment that intersects with a memory impairment would be sufficiently problematic to revisit those recommendations. As is usually the case, much of the visual accessibility is predicated on someone having a good memory. There’s also a minor intersection with regards to memory and physical accessibility when using a card holder, but the reference card provided mitigates a lot of this. Otherwise there are no significant intersectional issues.

The Fox in the Forest plays reasonably quickly – at least as far as individual rounds go. You play to a set point total, but really whatever that total ends up being is entirely up to the players. The quick game suggests fifteen, the ‘full’ game suggests twenty one, but there’s nothing to say you can’t play ‘one and done’ and you’d likely get the whole thing over and finished with in ten minutes. The tourney structure is valuable in de-emphasising the role that luck plays in the initial deal of cards but its not vital, and there’s no reason all rounds need to be played in one session. You could easily play them over multiple days if you like. That’s handy, because as this is a two-player-only game, when one player drops out the game is over.

Conclusion

The Fox in the Forest achieves a respectable performance here in our teardown – that oscillating dynamic of playing to win versus playing to lose creates an interesting cognitive profile but overall there are reasons to be hopeful that it might be playable for a wide variety of people.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | A |

| Visual Accessibility | B- |

| Fluid Intelligence | C |

| Memory | C |

| Physical Accessibility | B |

| Emotional Accessibility | B |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | B |

| Communication | B+ |

I also like the way that this mechanism creates opportunities for face-saving explainations of poor performance. I especially like it because I rely on it myself to pretend that I have the slightest handle on the best way to play a game like this. If I don’t want to admit that I simply don’t understand the whole trick-taking system I can say ‘I was playing to lose’ and it will explain and justify a whole range of otherwise baffling decisions.

While the Fox in the Forest may not have wowed me as an overall package, I’d love to see another game that explored this curious system of incentivising people to play to lose right until they can’t lose badly enough for it to be worthwhile. That central innovation is the main reason why we gave the Fox in the Forest three stars in our review. As is often the case, others have considerably greater affection for this game than I do. Mrs Meeple is amongst the members of that group. If you fancy it and think you could play it you should probably take my opinions and stick them somewhere so deep in the forest that even a fox can’t find them.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.