| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Karuba (2015) |

| Complexity | Light [1.43] |

| BGG Rank | 600 [7.17] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Rüdiger Dorn |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Do you like archaeology? You do? What about bingo? You do? That’s absolutely smashing because boy do I have a game that’s going to scratch all kinds of your itches in all kinds of your crevices! Warning though, there is a non-zero chance that I will misspell this game as akubra constantly through the text. No special reason – just because that’s a kind of hat I used to wear before the internet turned hats into the all-but-exclusive calling card of the odious internet troll. M’lady. This game is actually called Akubra. No! Kubara? KARUBA.

This… this is going to be a rough review.

This is the most lucrative form of cultural appropriation

Karuba was one of the nominees for the 2016 Spiel des Jahres. While it didn’t win (being up against Codenames meant it was a tough year for contenders for the title) I certainly understand why it was shortlisted. It’s almost effortless to learn, and effortful but not complicated to play. It’s got enough randomness to give it flavour, but not enough to make it distasteful. It’s got lovely components and a nice thematic hook. It’s a charming package wrapped around a very likeable game engine.

A sun kissed island

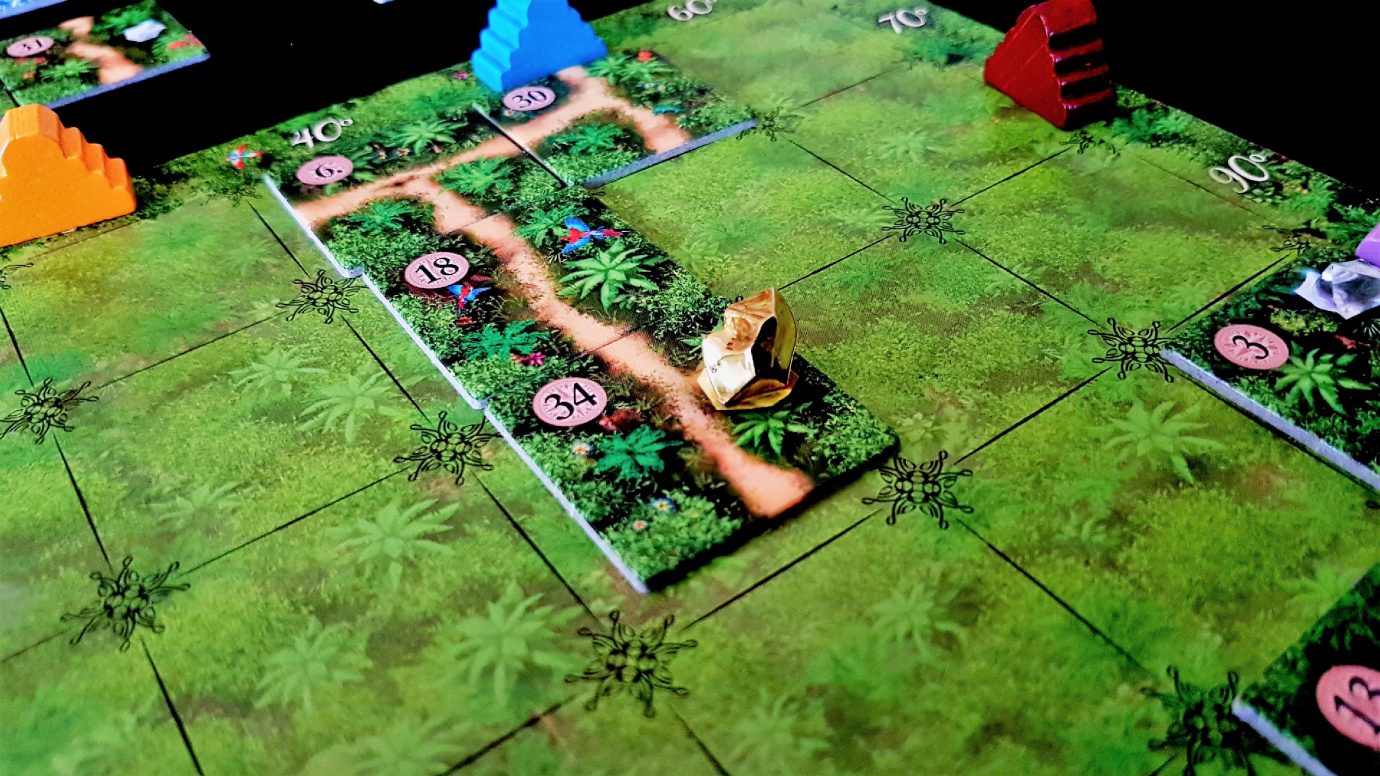

Let’s talk about about how it plays. First of all, each of us gets an individual player board that represents the forgotten island to which we have found ourselves drawn. At the top and right edges lies the jungle, and that is where the temples may be found. At the left and bottom is the beach, and that is where our adventurers land. Our job is to get the right coloured adventurer to the right coloured temple ideally before everyone else at the table. In order to do that, we place tiles that represent paths through the jungle – each of us gets a set of thirty-six identical tiles that permit us to do exactly that.

Bring your wellies

One player is designated as the ‘expedition leader’, and they shuffle up their tiles into a face down stack. They’ll be drawing these and intoning to the table the number of the tile that’s next to be placed. They don’t know in what order the tiles are going to arrive and neither do you. That’s the game!

I wanted the nearest dentist and this is where GPS sent me

The expedition leader will slip the topmost tile off, every round. ‘Two little ducks, twenty two’, they’ll say. You might even laugh, although I’d advise shutting down that nonsense right from the start. You’re adventurers on a forgotten island, and it does a disservice to your gallantry and tomb-raidering to diminish you with such lazy bingo references.

Everyone else arranges their tiles around their island, face up, so that they’re easily identified.

As you might imagine, this is a pain in the hole to setup each game

When a number is called out, you pick up the corresponding tile and place it on the island. Everyone has the same tiles, made available in the same order. At the start of the game, everyone also starts with the same adventurers located in the same position, with the same temples to find. You’ll arrive at some starting configuration as part of a negotiation at the table. In a two player game, the starting setup will look something like this:

Like mirroring screens on your phone

No matter how much you might like to, you can’t impact on the state of another player’s island. Everyone is largely playing a solitaire game of personal route-planning and optimisation. Everyone is using the same basic bricks to build their roads, and they’re all trying to get the same people to the same destinations. You’re also not taking turns as such – you’re all placing these tiles largely simultaneously, and you all have to place them in exactly the same orientation. Roads don’t need to connect, but the number is always played in the top left of the tile regardless of how preferential it might be to rotate it ninety degrees or so. Your goal, in the end, is to load your thieving pockets with temple treasures and the shiny baubles you’ll find discarded in the forest.

Cha-ching!

You might be pursing your lips in stern disapproval at this point. After all, it doesn’t seem like there’s much room here for strategy – you all have exactly the same information and the same ability to act upon it. So, where’s the game? Where’s the game, Michael?

Well, the game is in the fact that all that will happen if everyone does the same thing is a draw, and everyone is going to have a different view of how best to optimise the path from one adventurer to their destination. You can certainly mirror the person opposite you and guarantee you both have the same map at the end but you’ll both lose out to the third player that’s been forging their own individual path with no competition. See, getting to the temple first is a big deal because it means you get the most lucrative treasure. However, you still get treasures for being second, or third, or fourth. Letting someone beat you to one temple might mean you get a comparatively uncontested run at another two.

Cup of tea, number three

Everyone can see what the set of tiles available to be played are going to be, but nobody knows the order in which they’re going to be revealed. That gives plenty of opportunities for people to build contingency planning into their placement. Adventurers can’t leap-frog or pass each other. If you have a lot of adventurers making use of a very thin path you might find them stubbornly staring at each other like cars on a dirt-road in the countryside. Someone is going to have to reverse to a nearby passing place, and if you haven’t built one of those you might well find it impossible to get anyone moving. But then, if you can forge individual paths for each adventurer, maybe you don’t need those passing places. How conservatively do you want to play? How flexible do you want to be?

We place a shiny gem here too

Efficiency of tile placement is important, but as soon as the last tile is drawn the game is over. Or, as soon as someone has all four of their adventurers in the temples, the game is over. And here’s the kicker – you can only move adventurers by discarding a tile. You decide not to place it, and move an adventurer up to a number of spaces determined by the edges that the visible path touches. The most flexible tiles for path building, in other words, are also the ones that let you move your adventurers the farthest. And more still – you can only collect the diamonds and gold nuggets you pass on the road if you land on their square. There’s no Pacman style gobbling up of dots to the accompaniment of a zany wakka-wakka-wakka noise. Looting this island takes an almost martial approach to marching discipline.

The islands take shape

It only takes a single tile that has been placed differently on two boards for the whole calculation of the game state to change. As such, while it seems like there’s a simple exercise of rote route-building embedded in the experience, in reality divergence is all but guaranteed. Some people will want to create the shortest path from adventurer to temple. This ends up leading to long, thin and intensely fragile placements that are highly optimised but very dependent on exactly the right tile appearing at the right time. Some will build redundancy into their island so as to take tactical advantage of situational tiles and also to eliminate potential logjams. Some will emphasise the placement of gold and diamonds so that they’re most easily plundered on the way to the temple. Some might look to focus on a subset of the temples so as to simplify their jobs. Others will want to keep their options open, committing fully only when it makes sense in the economy of play.

‘Ask for more, 34’.

‘Can I have a gold nugget then?’

It’s also the case that often people will find themselves acting as a kind of social accelerant on the game for everyone else. Discarding a tile is an aggressive move – it says to everyone ‘Brace yourselves, I’m going in!’. Everyone that has been keeping their powder dry until that point is going to regret holding off on firing the first shot, because sometimes the distance between your adventurer and the finish line looks awfully large. That immaculate network of multiple routes to victory can seem indulgent when you remember you can only move one adventurer at a time anyway. Still, redundancy of the network gives you greater opportunities to spend your movement allowance in the best way – moving those adventurers that can most optimally gobble up the shiny, shiny gems.

And they’re off!

The sudden lurch of a player towards a temple also creates a lovely kind of economic volatility. Being the first off of the starter blocks can be vital if it’s a race. What happens though if you lunge towards a temple and nobody follows? In a sprint you might never notice until you’ve reach the end and found everyone else is just watching you politely from the starting line. In a game like Aku… Kur… KARUBA… well, you might find yourself jogging to a halt and then just hovering where you are, ready to sprint and cement your advantage if someone else should look speculatively in the direction of the temple. Once an adventurer lands in a temple, they don’t move again – you need weigh up whether to sacrifice the glittery prizes on the way to the temple, or move more inefficiently in order to pick them up. Just because you can make it to a temple, it doesn’t mean you need to do so right away, or even at all. That all depends on how competitive the race is. Even If you have to make a long trek to the yellow temple, it might be worthwhile taking your time if you look over at your opponent just to find out if they’re really a threat.

Good luck getting to purple then

On the other hand, if you mess around too much you might find that someone else has stolen a march on you before you noticed. In attempting to race them to the end, you might also find that you set the scene for your own obliteration. You can be left off balance if they use your distracted stumbling as an opportunity to build a path to a temple you had mentally marked off as ‘safe for plunder’

In other words, don’t let the mechanics fool you – there is a game of real variability in here even though nothing about the design would actually go out of its way to suggest it. While it’s an intensely solitaire game at times, it’s also a game that is equally intensely collaborative in the ever-shifting economic exchange rate between time and profitability. You’ll never directly impact on what an opponent is doing, but indirect impact can be palpable. It sometimes feels a little lonely to play Karu… I mean, Ku… no, I was right the first time. It sometimes feels a little lonely to play Akubra, but it’s never a game where you can focus purely on yourself. You might be lonely, but you won’t be alone and it’s risky to think you are. In other words, the core criticism I see repeatedly leveled at Karuba (it’s a solo bingo game) is simultaneously understandable and widely off-target.

Second place is better than nothing, right?

With that in mind though, let’s also not oversell what Akubra accomplishes. It carves out a lovely twenty or so minutes of gameplay and fills them full of decisions that are simultaneously trivially easy and intensely contemplative. That’s certainly not nothing, but the accomplishment is also pretty much the minimum I ask of a game. The implicit request I have every time I open a box is the same for every single title – please don’t make me regret this. I had a blast playing Karuba. We played it several more times than I felt was needed in order to get a fair, accurate opinion for this review. If someone picked it down from the shelf I’d certainly be up for playing it most of the time. It is equally certainly though not likely to be me that reaches for it first. Karuba meets my implied request with cheerful aplomb, but it also doesn’t stretch itself to do more.

While I dispute the idea that it’s basically a multiplayer solo game, I also do think that it places too much emphasis on indirect interaction. If I see someone racing away to a temple, I want to be able to do something about it other than just give up instantly because it is mathematically impossible to catch up. I applaud how varied the setup and play can be, but I also lament a little how tightly constrained that variability becomes after a few plays. I admire the design of the simultaneous placement that eliminates downtime, but I also resent the setup that goes into painstakingly ordering tiles so I can pick them out when they’re called.

I can all but guarantee that if you think you’ll like this game you’re almost certainly right. Despite my minor objections above, it doesn’t really put a foot wrong. It takes a nice idea and competently executes it in a format that will alchemically convert your invested time into fun. It’s just I have a lot of games that do that already, and if you’re reading this blog there’s a fair chance you do too. As such, I can’t really muster much enthusiasm for why you should pick up Karuba instead of playing one of the undoubtedly equally fun games you already have staring at you from your shelf.