Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Hanamikoji (2013) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium Light [1.68] |

| BGG Rank | 251 [7.48] |

| Player Count | 2 |

| Designer(s) | Kota Nakayama (中山 宏太) |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Chinese/English/Japanese edition

Introduction

No need for a begrudging summary of the review here – Hanamikoji is great and I recommend it to everyone. At least, I recommend it as a game that can be relied upon to generate considerable amounts of fun – our four and a half stars rating isn’t a lie in that respect. We need to go deeper than that here on Meeple Like Us though – we always need to go deeper. We’re the Inception of board games in that we run on way too long, go far too deep, and end up being confusing and alarming in equal measures. And, just like Inception, we’ll end with a whimper in a way that leaves you deeply unsatisfied and resentful of the money you paid towards your ticket.

Sound like fun?

No?

I don’t care, we’re going anyway!

Colour Blindness

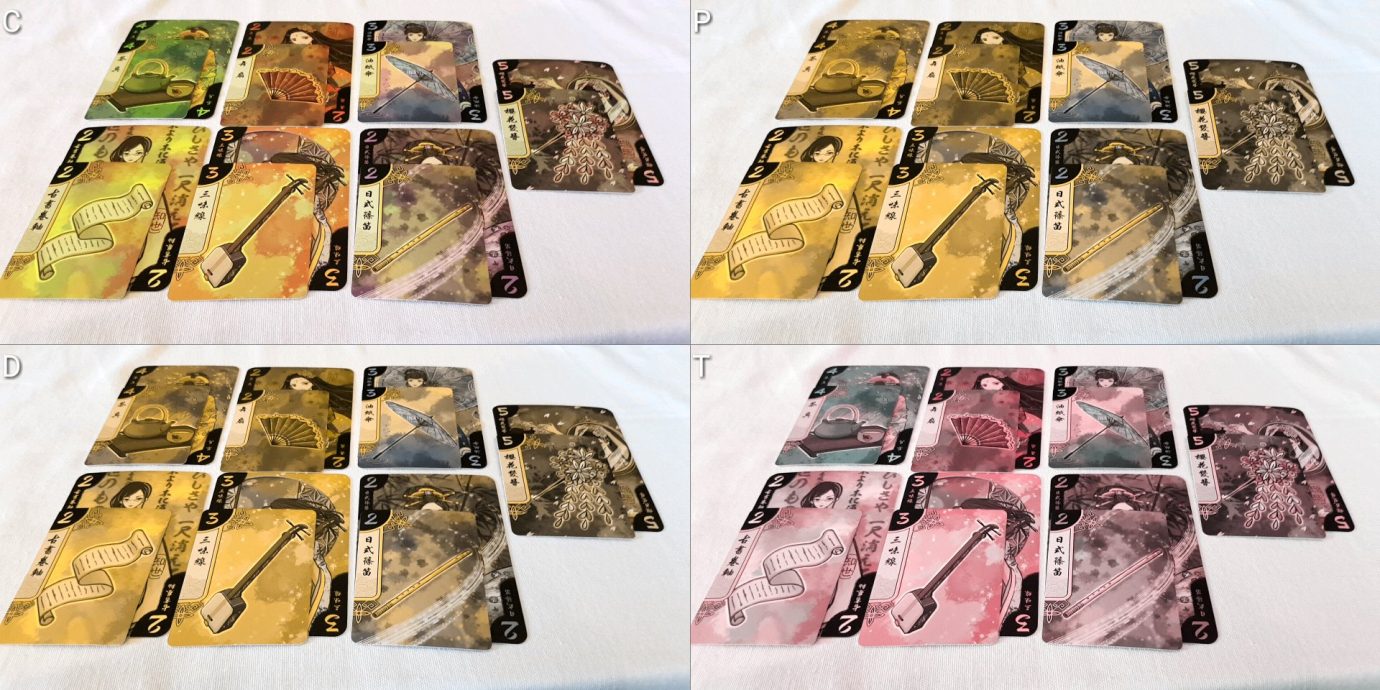

I can’t think of another game we’ve looked at on Meeple Like Us that has approached colour blindness in quite this way. The colour palettes are a problem, there’s no denying that. Not just in terms of flow of play but in terms of what it does to the beautiful artwork that is otherwise such a visual treat.

Geisha of the Blasted Lands

This is true too for the cards that represent the items that you will be using to lure individual geisha to your restaurant – the colour scheme here is problematic in all kinds of ways.

The colours of consumerism

Before we get our tar and feathers though, let’s look a little bit closer at one of the more initially egregious examples of colour palette overlap – the bottom left two geisha as shown on the image above.

Lutes and learning

Note here that each pairing of geisha and card has unique art, but that alone isn’t sufficient to offer clear differentiation. Our view on Hanabi for example remains that the different patterns of fireworks are distinguishable but not describable. Here though we can see that the item you need to provide for the geisha is prominently reflected in the item card you have. The musician geisha needs a musical instrument, the scholarly one requires a scroll. The geisha to which the item is matches is very prominent and layers in a considerable amount of redundancy to the channels of information. It would have been better for the colour to be distinctive but this ensures that you don’t need to rely on occasionally overlapping numbers to allocate cards into pairs.

I’d only offend everyone if I tried to pronounce these

Coupled to this, the name of the item is also represented in Kanji characters – while this isn’t entirely accessible in its pure sense (again, a thing we discussed in our Hanabi teardown) it’s also shown on the matching geisha so it’s easy to match item to the target in the tableau. Hanamikoji provides not just one channel of redundant information – it’s several, all at the same time. It’s really nice, even if those with colour blindness aren’t going to have quite as smooth an experience with the game as others because of the palette.

We strongly recommend Hanamikoji in this category.

Visual Accessibility

The card art is distinctive and well contrasted, and while the colour palettes alone aren’t sufficient to uniquely identify a card when someone has a visual impairment they do offer a reasonably solid additional source of information. However, this is still a card game with very few tactile indicators of game state (victory markers and associated progress on the geisha aside) and as such it presents severe obstacles to anyone who would like to play the game when taking into account total blindness. There are only a small set of cards though and this is one where if players are not too concerned about modifications it would be possible to add small, unobtrusive tactile indicators.

It doesn’t matter if you can see the cards – you won’t be happy with what you do regardless

For those with less severe visual accessibility needs, there’s reason to be positive. You deal with a relatively small hand of cards at a time – it begins with a maximum hand-size of seven but will gradually get smaller as the game progresses. Your choices are tightly constrained by your actions – even when an opponent offers you cards you will be deliberating between four cards, in two pairs, at most. It’s possible to count potential control over geishas by fingering the cards on each side of the table, which means for the most part a player simply has to focus on the cards in front of them. Examination with a visual aid will be sufficient for this if it’s possible, and given the highly distinctive nature of the art I don’t think it needs to be particularly close in terms of close inspection. Assessing the tableau against the choices a player has available though is going to need a fair bit of consideration, and losing the visual angle of this isn’t trivial. However, there are only seven geisha in total and if necessary, much as we recommend with Codenames, another format of representation could be used without too much onerous administrative work. You could hold the state of the game easily in a spreadsheet for example, allowing variable font sizes to stand in place for the physical representation of the game.

The individual markers you get for actions are double sided, and you flip these over to indicate that action has been spent. There are only four actions though and while it’s nice to have these reminders available they’re not strictly speaking necessary – they could be tracked in any number of other ways such as on a notepad or laptop. Or, if appropriate, simply held in memory – the small pool of possible things you can do makes that feasible in a way that wouldn’t necessarily be possible in a game with a larger set of choices.

Flipping yourself off

The kanji characters are unlikely to be particularly useful in the respect of providing visual information here, but as noted above in the section on colour blindness they are a third channel of information. A such losing their differentiable elements wouldn’t necessarily impact on the playability of the game as a whole.

We’ll recommend, just, Hanamikoji here for those with minor to moderate visual impairments. Those with total blindness can most likely play if some method of disambiguating cards in hand can be found, but the amount of additional cognitive burden required to make meaningful decisions with no visual reminders of game state is likely to make it a punishing prospect at best.

Cognitive Accessibility

The rules in Hanamikoji are about as simple as they can be, and it offers a considerable degree of physicality to the numeracy. As an example. you can see who is winning a geisha by the number of cards they have played. Knowing how many cards are in the deck for each geisha is valuable, but that information is presented on each of the cards in the game. As is often the case here with lighter and simpler games we don’t have any serious concerns in the cognitive accessibility category for the ruleset.

The problem is how those rules come together to create circumstances under which players make decisions, and this is an area where Hanamikoji accomplishes miracles with its svelte systems. The process of making an offer is fraught with the need to think through opponent responses to your offer, and your responses to those responses. You need to be able to guess at likely actions a player might take, and how that would shift the economy of the game. You need to be able to see feints and assess intention, and evaluate both against the cards you have in your hand and on the tableau. It is really difficult to do this well. It involves building a kind of mental matrix of how likely you are to win each card and adjust it as new information becomes available. One card is always missing from the round, and so you don’t even have the guarantee that all cards will eventually come into play. You need to decouple your actions from the outcome by playing secret cards and discarding before the full state of the game is known. The key issue here is that you’re not actively playing your own cards really – you’re playing the cards that are left over after your opponent gets to take the choicest selection. Hanamikoji is not technically complicated but it is strategically complex.

It’s nothing about the game itself that causes serious problems – it gives you abundant hints as to game state, provides trackers for everything that needs tracked (you can always check your secret card, for example), and packages it all up in a very simple set of rules. It’s not even as if the game state ever becomes particularly complex – it’s just that within the space of four actions you make some intensely impactful decisions, and those need meaningful consideration from a whole range of perspectives. Hanamikoji is a good example of a school of game design that emphasizes a small number of difficult decisions other a huge number of simple decisions. In order to pull that off, you need to make sure that players are incentivised to consider each decision.

I don’t even really see there being an accessible variant of the game in here – it’s just too much about the flow of uncertainty implied by making decisions within viciously tight constraints. Those with memory impairments alone though are better served than those with concerns about the accessibility of the game in the fluid intelligence category. As such we’ll tentatively recommend Hanamikoji for those with memory impairments, but we can’t recommend it for those with fluid intelligence impairments.

Physical Accessibility

You deal with a hand of seven cards at most, and a single card holder will be suitable for this because they can be tightly compressed to reveal only the number, colour and item name. There are very few physical requirements in play – all that is needed is to make offers of cards, and place cards that you have selected against the tableau. None of those things require the direct involvement of a player with physical constraints. Similarly, when an action is taken its token should be flipped over to the used side but this isn’t actually necessary if it’s likely to be a problem. One player, assuming someone is able to handle this part of the game, could manage the tokens for both without any difficulty.

If verbalisation is necessary, each of the actions has its own unique terminology and cards within a holder can be identified by number. ‘Make a gift of cards four, five and seven’, or ‘A competition with pairs two and three and five and seven’. All of the actions are numbered too so as to permit even more succinct representation. ‘One with four’ or ‘Two with three and five’.

We recommend Hanamikoji in this category.

Emotional Accessibility

You will always be under pressure in a turn to make a difficult decision – you very, very rarely get to do something unambiguously positive. That means there are lots of opportunities to get locked up in uncertainty, lots of opportunities to make mistakes, and lots of opportunities for players to feel stupid for what they’ve done. All of the decisions you take here are challenging, and because you only have four actions their impact is considerable. There’s absolutely no chance to undo a critical mistake – there just isn’t enough time in the game within the play space of four actions.

A win is declared when a player controls four geisha or a total of eleven points of geisha. This is quite difficult to do which does mitigate some of the luck of the draw – if nobody wins the game rolls on with the ownership of geishas persisting. Winning in a single coup de grace is very challenging. Hanamikoji is an interesting game in that what you almost want to draw is a bad hand of cards so that when you make an offer you don’t watch your opponent take something that you really want. As such, there is a very different feel to the usual randomness of a card based game. You rarely look at your hand and feel despair – you look at it and wonder what it means for how you need to win. However, that doesn’t change the fact that the deck gets shuffled, cards get dealt out, and one person is likely to have a better hand of cards than the other. Since the game is explicitly a duel, albeit one without the sheen of intellectualism associated with something like chess, the consequence of losing can easily be mentally cast into ‘I was just bested’.

The fact it’s quite difficult to win in a round though adds a problem here – it’s difficult but not impossible. Given that the game has a whole system of persistence of advantage it can be emotionally troublesome to be knocked out of play in a single round. That can feel an awful lot like you just weren’t smart enough to be playing, and that can lead to cycles of self-reproach or upset. It’s possible too in the final reckoning to lose by a lot.

Much of this is mitigated by the length of the game (which is short) and the pace of play (which is brisk). This kind of issue stings most in long games where there’s more involved in a replay than just shuffling a deck and starting again. While there are some things that need to be taken into account in Hanamikoji, we can still offer it a recommendation. Just… be wary.

Communication

There is no formal need for communication, and no need for literacy during play. We strongly recommend Hanamikoji in this category.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

Mrs Meeple asked, with a somewhat evil glint in her eye, if I was going to be as critical about Hanamikoji’s gender balance as I am about those that have an entirely male roster. This is an issue I grappled within the One Deck Dungeon teardown, and my opinion really remains the same – yes, it’s a problem. No, it’s not as big a problem as it is for other games. There’s a world of difference between subverting the status quo and upholding it, and Hanamikoji’s gender and ethnic representation has to be viewed in that light. The manual does default to masculinity though which does kind of undermine my point a little. I think from context those are mistakes from translation since much of the explanation in the rules is pointedly gender neutral.

There’s also another reason why an all women roster of character is not quite as troublesome here as it is for other games – you’re not expected to be any of the geisha. You don’t pick one of these and play them in a game – you’re the restaurant owner trying to recruit them to your venue. As such, there’s no real need to concern ourselves about a sense of ownership or identification. They are not you, you are not they. This is different again from One Deck Dungeon where you took on the persona of the characters in the game. There is an important element of background representation in games but issues of representation are especially pronounced when we are expected to put some of our own sense of self into the characters.

It’s all fine. It’s really all fine.

So – yes, it’s an inaccessibility and I can imagine it being sufficient to keep some people thinking it’s a game for girls. But no, I don’t think it’s a major problem and it’s not something that will keep me up at night. I will repeat what I said in the One Deck Dungeon teardown – some might legitimately think of this as a double standard. I prefer to think of it as a nuanced standard. These two circumstances are not equal.

As far as price goes, I picked up Hanamikoji for £17 and I think even with the restrictive player count it’s worth every penny of that. This is a game I expect to have on my shelves forever. However, it also seems to be a little difficult to find at the moment and as such prices on Amazon and other sellers are extortionate. If you can pick it up for around its RRP it’s well worth the money. If you can’t find it for a reasonable price, then you can always pick up Jaipur until you can.

We recommend Hanamikoji in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

Colour is a very useful channel of information here, and if someone was concerned about the intersection of visual impairment and colour blindness we might be inclined to be a good deal more tentative in an already very circumspect recommendation. Physical impairments combined with communication impairments are often a problem when considering verbalisation, but here it’s possible to very compactly convey key information through assent or dissent.

There is a hidden hand of cards, and if a visual impairment intersects with a physical impairment that impacts on mobility it might become difficult to do all the necessary close inspection that would be required for meaningful play. That’s not likely to be too significant an issue though given the relatively slow churn of cards and the limited number of actions you take during the course of a round.

Games of Hanamikoji play very quickly – around fifteen minutes, barring accessibility considerations. A winner might not be declared after a single round, but the rules suggest that you set a round limit and declare a winner at the end of that based on who has the most points. That permits you to scale, within the limits of the round structure, how long a match should go on. That’s important in a game like this because otherwise there is no ability for a player to drop out without the game having to end.

Conclusion

Given how much decision anxiety Hanamikoji has given me, it was inevitable that it wouldn’t excel in our cognitive analysis. Otherwise though we have a reasonable strong performance for a game that I would enthusiastically recommend to everyone.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | A- |

| Visual Accessibility | B- |

| Fluid Intelligence | D- |

| Memory | C |

| Physical Accessibility | B |

| Emotional Accessibility | B- |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | A- |

| Communication | B |

As always, these recommendations must be viewed in the context of their associated discussions. It’s still not a game that will work well in situations of total blindness, and the emotional impact of play is going to be influenced heavily by the people actually playing. That’s true in all circumstances of course, but especially true here when each offer of cards is the game equivalent of trying to slap someone in their face.

Hanamikoji is a lovely game – four and a half stars of lovely. While it doesn’t emerge from this teardown as elegantly coifed as the characters on the cards, it can hold its metaphorical head high. If you like the sound of the game, and I sincerely hope you do, then you should consider it for inclusion in your own game library as soon as is feasibly possible.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.