Table of Contents

| Game Details | |

|---|---|

| Name | Fresco (2010) |

| Review | Meeple Like Us |

| Complexity | Medium [2.63] |

| BGG Rank | 459 [7.25] |

| Player Count | 2-4 |

| Designer(s) | Wolfgang Panning, Marco Ruskowski and Marcel Süßelbeck |

| Buy it! | Amazon Link |

Version Reviewed

Introduction

I liked Fresco a lot more than I thought I would when I opened the box. It look like a dozen other board-games with interchangeable components, and that doesn’t exactly wet my whistle. It grew on me considerably with familiarity and while I don’t see it displacing certain other games in my collection it certainly deserves the four stars it received it in the review. We don’t get to have a long lie just because we gave you our opinion though – our taskmasters are harder than that on us. Our next job here on Meeple Like Us is to send our apprentices out to paint a word picture regarding its accessibility. Is it a masterpiece, or a clumsy amateur restoration? Let’s find out.

Colour Blindness

Colour is a hugely important element of Fresco, and I am very impressed by how it’s been approached in the delivery. This could so easily have been a disaster had it been tackled with less surety of touch. Don’t get me wrong, colour blindness is an issue but the component design has done everything feasible to limit the impact.

Let’s be critical to begin with, because that won’t take long. The only substantive problem with how the components present themselves in colour is that the master painter meeples used to indicate mood, turn order and scoring use colour as the sole channel of information. The colours chosen (red, green, blue and yellow) are all problematic in this category:

A problem! A problem!

But here’s the first nice touch – the master painters have flat tops, presumably to indicate some kind of jaunty artist beret. That means that where colour-blindness is an issue you can just flip the meeples upside down to give an instant way to differentiate between them. No need to go scrabbling for replacement tokens.

Where did the problem go??

The cubes used to represent colour map on to the portion of the spectrum they represent. We have red, yellow and blue cubes for primary colours. Green, purple and orange for secondary colours, and pink and brown for the third tier of colours. All of these are a problem from a palate perspective:

Another problem!

That’s true in theory, but in practise different sized cubes are used to represent the different hierarchies of colour. Secondary colours are bigger cubes than primary colours, and tertiary colours are bigger than secondary colours. While this isn’t perfect, it is a very good solution to the problem posed by colour blindness.

Oh, no problem! This is a rollercoaster of emotions

There are still going to be moments of minor confusion because while the cubes are different sizes that doesn’t necessarily aid in identification at a distance. It’s never going to be the case though that someone need query colours and risk revealing gameplay intention as a result.

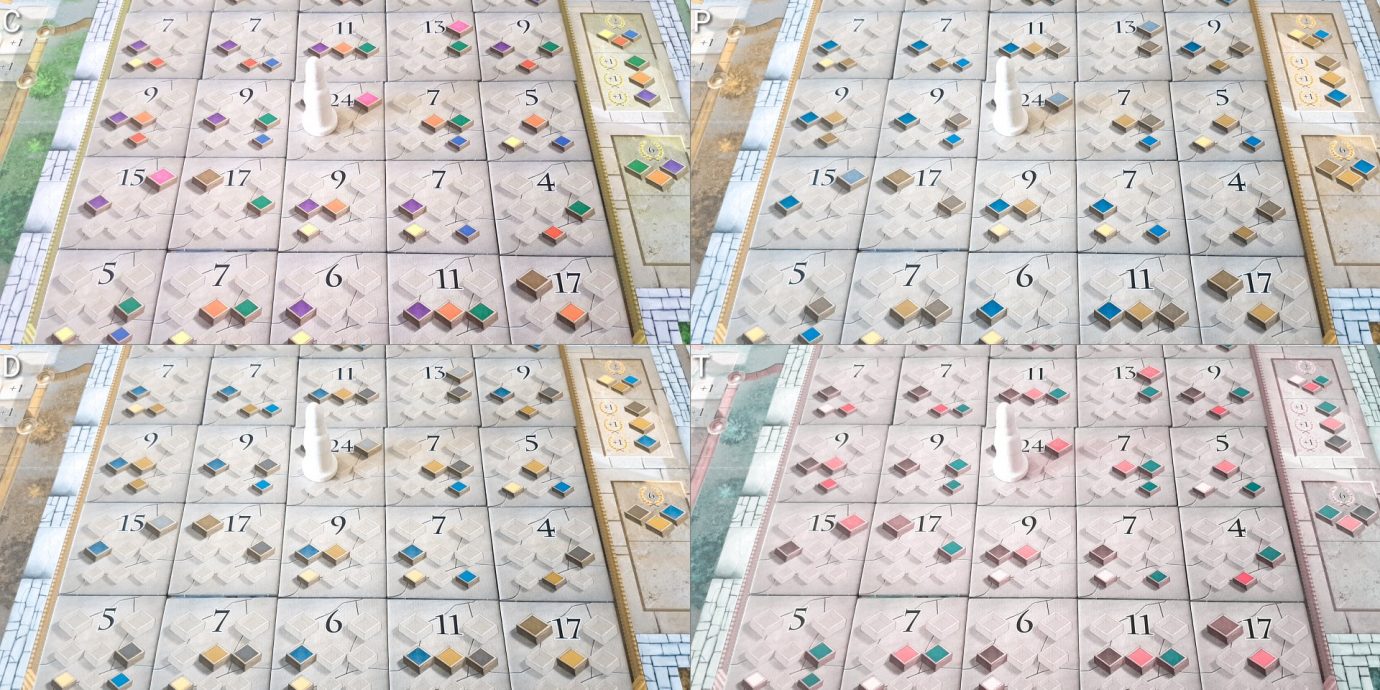

This extends to the indicators in the fresco tiles, and this has another nice feature in that the colours required all have a positional aspect as well as a colour aspect. Yellow is always bottom left, blue is always bottom right. Brown is always top left, and so on. The icons on the tiles too obey the size rule, so that the primary colours are small and the secondary colours larger. What overlaps in palate exist are compensated, at least in part, by additional sizing information.

Paint away, people!

So, while colour blindness is going to have an impact on the ease of play it’s not going to be so deleterious an impact that it makes play impossible. In a game all about colour manipulation and management, that’s quite a feat.

We recommend Fresco in this category.

Visual Accessibility

We have a less encouraging scenario here. There is a lot of visual evaluation of game state that goes into play. Players with total blindness are not going to be well served by the systems of the game. Those with less severe visual impairments will also have problems in making meaningful decisions about the game ahead of them.

On the simplest level, the various score trackers, mood trackers and wake-up trackers are well contrasted and sufficiently restricted in information content to be accessible with the use of an assistive aid. Colour mixing is straight forward, and has tactile cues through the cubes. Unfortunately, this doesn’t actually help in inventory by touch because the different sized cubes vary only by tier of colour and not colour itself. It’s not possible to tell a red cube from a blue cube from touch, although you can tell a green cube from a yellow cube.

What has it got in its pocketses

The biggest problems though lie in making meaningful choices in the marketplace, in the workshop, and in the cathedral. All of these require forward planning that is best supported with visual information such as grouping cubes together based on their intended destination on the fresco, or coupling them together for the role they’ll perform in a future blend. However, the nature of how the game evolves means that this is going to be a constant recalculation as market squares are claimed or fresco pieces restored.

Get to work

Assessing the fresco means considering what’s in the market, versus what’s in your inventory, versus what you can get out of the workshop. This is all related and linked – your workshop actions will depend on what you get out of the market and what you use in the fresco, and your fresco actions will be influenced likewise by what you get out of the market and what you can later blend. This involves a lot of cross-checking.

The market provision changes very rapidly due to its often central role in planning, and this means that it’s not easy to simply memorise what’s available. The churn is too significant for that. The fresco though changes more incrementally, and it only ever becomes easier to hold in memory as tiles are used up. Still though, you need to do a lot of forward planning and that is eased by the availability of visual information.

The game makes use of three denominations of money, and while these all have a different size it’s not easy to tell the difference between adjacent denominations. Some varying of form factor as well as size would have been very welcome here.

In for a penny

Interestingly, there is very little reason for players to worry about the information in front of other people. Most game information is either secret (paints, money and so on) or revealed simultaneously and so has no bearing on the decision you might make on your turn (apprentice allocation). As such, while Fresco does have a lot of individual game state you only ever need to worry about that which is in front of you.

We don’t recommend Fresco in this category, but if you are really set on it it’s likely playable with care. It’s likely though to be an exercise in finding some workable form of representational state management and that’s going to have a noticeable impact on game flow.

Cognitive Accessibility

The ability to chain together individual actions into a logical workflow is critical here. Consider the calculations of a player that is spending two market actions, a cathedral action and two workshop actions. First they enter the market, and have to think about what paints they want from the choices they have and the money they have available. The paints before them may not match what they were when the decision to go to market was made, so a degree of flexibility is needed. That flexibility is informed by knowing what you could restore in the fresco either this turn or the next. Paints might be bought for immediate use in the cathedral, imminent use in the workshop, or as preparation for future turns. That latter step involves a model of risk, reward and diminishing opportunities that is informed by player actions, the likely intention of other players, and your own desires. Those looking to play competitively might also consider the benefit of trashing a stall so as to deprive other players of paints you believe they need.

Then you move on to the fresco, where the choices are a little more straightforward. You have a set of paints, and these can be used, or not, to restore fresco tiles. However, having the paint is not necessarily a good enough reason to restore a tile if it means you won’t have a colour that is required in order to mix up a key paint in the workshop. Spending your three primary colours on a three point tile, only to find you can’t now mix the green that would get you the brown, is a tactical blunder. The difference can be significant – twenty points or so. It’s important when at the fresco to focus on the larger picture. Teehee.

Then in the workshop you need to mix paints not for the fresco as it exists, but the fresco as you anticipate it will appear when your turn comes around again. As such, if you’ve seen someone stockpiling brown and pink you need to weigh up the chance you’ll get to pip them to the lucrative tile they’re working towards. Sometimes you’re best to focus on smaller yield tiles that have no competition, but you won’t know for sure what you can do until wake up times are distributed.

Even the wake up calculation is one fraught with logistical implications. Not just in terms of what order you get to pick, but in terms of how it impacts on your money and mood, and the order in which you might get to pick from limited resources. That in turn greatly influences the risk and reward of purchasing and mixing paints for specific fresco tiles.

The cognitive expense here is considerable, and it stresses both fluid intelligence and memory. The mechanics of the game are straightforward enough – the cost is in leveraging them effectively.

We discussed in the review though how Fresco permits for players of different level to play well together, and that remains true here. All of the above is important in skilful play, but you can get pretty far by just focusing on the opportunities you have at the time rather than trying to optimise the points you get out of every cube you have available. If you’re not of a competitive bent, there’s probably a lot of fun to be had in simply playing the game to restore the fresco rather than earn the greatest number of points. Some games have a core loop that is just satisfying independent of scoring considerations and Fresco is one of them. It’s enjoyable to carefully curate your paints until you have the right shades in the right quantities to reveal a piece of the artwork underneath the fresco tiles. If you threw in an image randomiser, that might be a game in and of itself.

You are still though asking a lot of players even when playing just for the fun of it rather than the challenge, unless you want to bypass all of the careful logistical manipulation at the core of the game. Even then while you would reduce some of the competition that leads to much of the fluid intelligence cost, the memory burden would remain.

I’d say that you’d have an easier time with other games we have actively recommended in this category, although if you are committed to Fresco you’ll likely find a way to make it work somewhat. Overall then, we don’t recommend Fresco in either category of cognitive accessibility.

Emotional Accessibility

Most of the competition in Fresco is in racing to get the paints, tiles and portraits that you want ahead of other players. When you’re trailing other players, you are entirely in charge of whether or not you can beat others to the punch – you pay extra for that, but it’s entirely within your control. It’s empowering to be in last place and able to set the pace of the game. However it’s also deeply frustrating as you watch someone else take the hit to mood just to beat you a key part of your plan. Still, that’s all one step removed and it’s not directly hitting at you – just your opportunities. The problem there is that even being blocked out of getting a paint tile can be the difference between your carefully laid plans yielding results or failing utterly. Once you’ve committed to a course of action and revealed it to the table, you’re stuck with it even if it’s obvious at the time of revelation that it’s going to result in an entirely wasted turn. There aren’t really any opportunities to undo your mistakes here, and the cost of a poor turn is substantial.

There is too an incredibly pointed form of aggressive competition in the rules – the ability of a player to forgo buying a paint in order to trash a market stall. It’s impossible to read anything other than malevolence into that because – well it’s entirely malevolent. The only circumstance in which that might be conducive to the communal experience of the table is clearing a poor stall of terrible paint that nobody wants. Otherwise, all you’re doing is pointedly and to your own detriment, robbing someone of paint that they might actually need. Doing that can knock someone entirely off the rails of their plan, and it is explicitly targeted at everyone that follows you in the wake up order.

Score disparities in Fresco are usually quite small at the end, although they will seem gaping during play before contracting dramatically towards the conclusion of the game. However, a string of good fortune can seriously catapult someone into what seems to be an unassailable lead. Individual turns can have large point yields if a player manages to grab a few large tiles with the blessing of the bishop. You might find yourself moving on thirty, forty or even fifty points if everything goes the way you would want. The turn order system implements a mechanistic rubber band for this, ensuring that until others catch up you’re the last to choose when to get up in the morning. This can be wielded as a weapon too. You can collaborative through the table make someone begin early in the morning and suffer a compounding penalty that cuts away actions. Or you can make them move last in every turn, severely curtailing their opportunities. If you’re on the receiving end of that it can be frustrating, but it does ensure that there’s an internal gyroscope of momentum that provides even the players that are behind with a chance of catching up and even winning.

Even so, until players have more familiarity with how the scores tend to swing this can be extremely discouraging. There’s little randomness in the game (the only randomness being how the fresco is set up at the start and what tiles come out of the market bag), so in the end if you don’t equalise the score at the end it can be a source of self-recrimination and the associated spirals that come with emotional control disorders.

Core to the issue here is that while everyone in Fresco gets an equal chance to play (or if they don’t, it’s through their own actions) it’s not going to be the case that everyone gets as much fun out of their turns as everyone else. Arriving at a market full of paints you don’t need isn’t fun or a useful allocation of an action. Shuffling into the cathedral only to find you can’t do anything is vexing. Seeing you’ve allocated three workshop actions on the expectation you’d get a particular colour from the market can be funny if you’re in the right frame of mind. Otherwise it looks like a massive waste of time and you don’t have a lot of that.

Overall, we’ll offer a tentative recommendation for Fresco here. The cost of failure is high, the competition over scarce resources is reasonably intense, and there are frustrations wall to wall associated with missed plays. But if you can work through all of that, the game’s internal balancing systems do tend to result in a more equitable experience than you might expect.

Physical Accessibility

The secret activities you conduct behind your player shield are likely to be a problem, both in terms of the constraints of your personal action board and also for how flimsy the shields are. You (or a stiff breeze) will almost certainly end up knocking them over and revealing more than you’d like about your progress and plans. The individual player boards are small and the apprentice meeples you place on them are equally diminutive. There’s no reason you need to use that board though – more accessible regimes would be just as valid provided you can show how many of each action you’re planning to take and have some mechanism of everyone simultaneously revealing them to the table at the appropriate time.

Teeny tiny meeples

Removing tiles from the fresco, certainly ones embedded within a neighbourhood of other tiles, is almost certainly going to result in misalignments and awkward nudging of pieces. There aren’t so many of these that it’s difficult to tidy up afterwards, but if compounded with fine or gross motor co-ordination issues this is likely to be a problem. It doesn’t have any gameplay impact though for someone to remove tiles on behalf of another player.

Manipulating cubes is a constant requirement of players, and here verbalisation is likely to be difficult due to the need to keep game state secret. Behind the player board you’ll be grouping individual cubes, often of different sizes, together according to intended usage. You might have one small area of your table available for your planned mixes, another for fresco completion, and another of loose paints. Even if you just have them all bundled in together in happy lump you don’t want it to be too easy for people to know what paints you have ready to go. That kind of information would hugely influence the future direction of turns in situations of high contention.

Verbalisation then is going to depend on the extent to which personal cube management is possible and for those cubes to be distributed back to the game state. It’s likely to reveal unintentional state leakage if someone has to reach behind a screen and extract them.

Overall, as a result of the complications associated with verbalisation, we can only offer a very tentative recommendation.

Socioeconomic Accessibility

Finally, here’s a section with a bit of (muted) good news! Even drawing as it does from renaissance conventions, women are represented reasonably well in some parts of the game, although less so in others – notably the box itself.

It’s like a Renaissance greatest hits album

It’s difficult to be too definitive about this though since some of the women are angelic representations and I believe Catholic dogma is insistent that angels, regardless of how they may present themselves, have no gender. That could potentially have been an interesting way to incorporate non-binary representation within the game but I’m not sure it counts if you need an understanding of obscure and conflicted issues of religious doctrine before you know it. In any case, even if this was something explicitly acknowledged within the game design the intersection of Catholic conservatism and progressive gender politics is likely to result in some… complicated feelings. Beyond that, women are present in the fresco itself, and in the many portraits that can be commissioned.

You can have all the diversity you like as long as it’s white

As might be expected, the art reflects the dominant ethnic themes of the period, which means that even Egyptians and carpenters from the Middle East were reflected overwhelmingly as white Europeans. There isn’t a lot of ethnic diversity represented in other words although given the often starkly racist paintings of the period that might be for the best.

Fresco has an RRP of £40, and that’s on the pricey side for a game that supports a maximum of four players. It plays reasonably well at two though, through the adoption of a dummy player that adds the necessary contention over resources. Consensus is that it works well at all counts, but is better with three or four. Out of the box though you’re getting a very good game with real lasting value. This isn’t ‘one and done’ – this is a game you can come back to again and again. As such, while the upfront cost might seem a touch large you’ll wring value from each pound that you lay down.

We recommend Fresco in this category.

Communication

There’s no formal need for communication during play, although being able to swear as someone takes that one piece of paint you really wanted can be very cathartic. There’s no reading level either – every element of the game is reflected in language independent iconography.

We strongly recommend Fresco in this category.

Intersectional Accessibility

Most of the intersections we might usually discuss here are already handled as a consequence of the individual categories. There are a few minor points to add though.

Much of the cognitive cost of the game relates to forward planning of actions, but some of it is down to the relationship between accumulated paints and their intended use-case. This becomes an awful lot easier to do when you can perform some grouping activity in secret behind the screen, and that in turn is going to depend on fine-grained motor control. If this wasn’t possible, the cost of almost every activity across the board is increased – cognitive cost, visual processing cost, and even emotional impact. Being sure of the paints you have and how they match opportunities is a core gameplay skill. While a physical ability to group cubes is not necessary, it is an important compensation for all other intersecting conditions.

The Fresco box suggests a sixty minute playing time, and while that’s probably true for experienced players it is, in my view, a very optimistic estimate. Ninety minutes is closer to the mark as a baseline expectation, with the appropriate adjustments on top of that being made to accommodate accessibility requirements. The end result is a game that is on the cusp of being long enough to exacerbate issues of discomfort, and this might well have to be taken into account. The game can reasonably easily support players dropping out though, and the mechanics of the dummy player can be brought into play if necessary to keep a game going on to its end. That won’t be an ideal solution, but a feasible one. Nobody need feel as if they are compelled to play through to the game’s termination.

Conclusion

Fresco is a great game, with some truly nice accessibility features for those with colour blindness. The nature of the game though, and the large amount of visual information required to spot opportunities and capitalise upon them means it doesn’t do particularly well in our deep dive into its accessibility.

| Category | Grade |

|---|---|

| Colour Blindness | B+ |

| Visual Accessibility | D |

| Fluid Intelligence | D |

| Memory | D |

| Physical Accessibility | C- |

| Emotional Accessibility | C |

| Socioeconomic Accessibility | B |

| Communication | A |

It’s always the case that games focusing on tactical and strategic considerations will disproportionately stress cognitive faculties. Fresco’s combination of secret planning and public revelation also creates physical accessibility issues that don’t lend themselves well to support.

We gave Fresco four stars in our review – while there are games that it can’t hope to unseat from my collection, I believe it would make a good inclusion in a game library that isn’t already well served for this style of play. However, the accessibility profile suggests that if this is the kind of game you might find interesting, you might have to keep looking for something likely to be playable for the widest diversity of players.

A Disclaimer About Teardowns

Meeple Like Us is engaged in mapping out the accessibility landscape of tabletop games. Teardowns like this are data points. Games are not necessarily bad if they are scored poorly in any given section. They are not necessarily good if they score highly. The rating of a game in terms of its accessibility is not an indication as to its quality as a recreational product. These teardowns though however allow those with physical, cognitive and visual accessibility impairments to make an informed decision as to their ability to play.

Not all sections of this document will be relevant to every person. We consider matters of diversity, representation and inclusion to be important accessibility issues. If this offends you, then this will not be the blog for you. We will not debate with anyone whether these issues are worthy of discussion. You can check out our common response to common objections.

Teardowns are provided under a CC-BY 4.0 license. However, recommendation grades in teardowns are usually subjective and based primarily on heuristic analysis rather than embodied experience. No guarantee is made as to their correctness. Bear that in mind if adopting them.